Architect Scott Merrill | A Behind-the-Scenes Travel Diary

A Behind-the-Scenes Travel Diary

To capture the story of architect Scott Merril, WTTW’s production crew, along with host Geoffrey Baer, traveled from Chicago to the offices of Merrill, Pastor & Colgan Architects in Vero Beach, Florida and visited several locations in Florida where Merrill has helped transform communities with his modest, forward-thinking building applications. In this Travel Diary, Producer Dan Andries shares some of his impressions of the trip.

Making Places

Scott Merrill is a man who is making places in a place with no history of placemaking. Someone who can do that well needs to be giving a lot of thought to the impact they are having on the world, like the very real, on-the-ground impact. It is a major responsibility. And it is not a job for just anyone.

While Merrill is not a household name, his story involves the kind of journey many of us make in life – at first, vaguely considered, following one thread or another until it leads us somewhere we hadn’t imagined, but somewhere in which we are able to find ourselves and our greatest ability to be significant; to the world; to our work; to our family and friends; to ourselves (if we were lucky). Looking at his story is worthwhile because the details of every life provide “examples of what it’s like to be human,” as Terry Gross, talk goddess of public radio’s Fresh Air noted about writer John Updike’s notion of “specimen lives”. Maybe we’ve done that (if we were lucky).

The Little Jet

You can fly direct from Midway in Chicago into Northwest Florida Beaches International Airport in Panama City, Florida. It’s the closest airport to Seaside Florida.

We were saving money and so we first flew into Tampa and then jogged back north to Panama City on this little beauty. Geoffrey Baer, our host, walking towards the camera wearing the glasses, is a plane nut. If you really want to know what the jet is, Ask Geoffrey.

We had 13 cases of equipment and luggage. When I saw the plane I thought that certainly they wouldn’t be able to load our gear on board and still fit the passengers. Somehow they did, we landed (in one piece) and here we are on terra firma – Geoffrey, cameraman Tim Boyd, and that’s associate producer Mary Fishman walking down the stairs.

Academic Village

Often the noisy headlines many of us are able to push away when we are deep in our familiar spaces of our everyday lives become powerfully resonant when you’re out of town. The news of David Bowie’s death came to me on the first day of shooting in Florida.

We were staying at The Academic Village in Seaside. The lit porch of the cottage can be seen in this photo. The cottages were built out of Katrina cottages and they part of The Seaside Institute, an educational outgrowth of the great interest in Seaside from designers, architects, city leaders, and students. I love these rooms. They are modest, comfortable, and feel very good.

I had trouble sleeping my first night and kept waking up, dreaming that the prior residents were returning from a party and would barge in at any moment, not maliciously, but nonetheless as intruders. I awoke at one point to the buzz of my iPhone – it was a text from a friend that David Bowie had died. This was at 1:53 am. I went back to sleep. When morning came I was a groggy guy contemplating Bowie’s importance. I played “I’m Always Crashing in the Same Car” on my laptop as I gathered myself for the first day of production, grateful I had paid attention to what was now his final album, Blackstar, released just a few days prior.

Robert Davis

This man owned some land, wanted to develop it, had some sensitivity as a designer and architect, but more importantly had the patience and a vision for a greater good beyond his financial success.

Robert Davis developed Seaside Florida, the town that Andres Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, and Leon Krier designed, giving the world of urban place-making a fresh run at old ideas like walkability, mixed-use buildings, limited parking, and community.

We are standing his porch on Seaside Avenue. Robert is elegantly attired. In his home are a number of similarly beautiful hats lined up in rows of aesthetic grandeur.

Davis was Scott Merrill’s first important client. Lured down to the panhandle by urban planner Andres Duany, Merrill and his wife Zo Anne were the recipients of Davis’ gracious care and guidance, and Merrill was able to do his first buildings quickly and inexpensively on land Davis wanted to activate into something that might bring a little money back. In the end, it was more than buildings that were activated – it was an architect’s career.

On the Porch of the Honeymoon Cottages

Note how we dressed.

If you look carefully you will see the guy in the dark wool sweater with the knit cap and the white jeans. That’s me. Sort of frosty along the coast in January.

These are the Honeymoon Cottages in Seaside, Florida. They are strikingly different from the buildings beyond them. Merrill says they were inspired by Thomas Jefferson’s small house on the grounds of Monticello where he lived while his masterpiece was being built. Built into the side of a hill, it was a two-story building that appeared as a single-story structure from one side. Here, the scrub brush on the dune obscures the ground floor. The repetitive simplicity of the cottages was exactly the point Scott and his client, Robert Davis, hoped to make about the potential for developing Seaside as a place of ordinary, vernacular beauty.

The buildings beyond, while striking, do not follow its lead. It is a strong example of the architectural conversation that is very much part of what Architect Scott Merrill: The Power of Simplicity is about.

Scott and his Desk and Papers

This work gives me access to places I wouldn’t otherwise be welcome and I take full advantage of my all-access pass. I hang out in someone’s work world and record what people are up to, what’s on their desks and bookshelves, become a familiar sight. Scott’s desk was alive with material, dense with material. Scott himself is considered and focused in how he speaks, how he writes, how he designs. Here at the desk, not so much.

Scott told me now that he is Driehaus Laureate papers like these are of interest to scholars at University of Notre Dame. To him they were nuisances from jobs in progress that he’s been happy to toss once a project is finished. Maybe these sheets are destined for a grander resting place.

Down in the Pit

Scott is very proud of his staff.

The two young architects on the left side of the picture are Claire Martell and James Michael, and they are representative of the age of Merrill’s employees. Scott’s partner, George Pastor, is the guy in the middle with the brown helmet.

Being on site as a project begins to take shape is both a joy and a necessity for Scott. And for his young architects, it is the moment in which drawings worked over in the wonderful abstract vacuum of a drafting program become real steel rods in the ground and heavy concrete blocks laid one at a time by a team of workers who are at it for hours every day. It is when a plan becomes something real and no doubt something less than ideal. But real is where it’s at.

This location was so incredibly cool. We are down in a trench that runs the length of the site. The wooden tower in the background is the height the buildings will be when they are finished in this corner of Windsor.

Rigging a Car with Cameras

I wanted a strong beginning to our program. I’ll leave it to you to weigh in on its effectiveness.

We planned a driving sequence. And it was a friend’s ecstatic comments about how the car is used in the films of Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami that led me to make the commitment to this approach. In a car, people are stuck and have to speak with each other – and that’s that. I spoke with our cameraman Tim Boyd about how to best do this (that’s Tim in the photo). I wanted it to feel like a movie made 60 years ago. For that we’d need a camera car and a bigger crew. Tim suggested we look at the GoPro setup WTTW had worked out for the series My Chicago. It had been road tested, and the equipment was still available. I was skeptical. But the clock and the budget said it was time to move forward. And so we did.

The morning of the shoot, we all met in the hotel parking lot in Vero Beach. Scott allowed us to take over his Volvo XC70. With the gaffer Louie DiMeglio, Tim ran cables and cords, rigged batteries, put mics in the vehicle and mounted the cameras on the interior of the windshield. Then we rolled, never cutting audio, and mostly never cutting the camera, for the next hour and an half.

We did a second pass with the cameras mounted on the hood, one turned to the windshield, the other to the road. The battery on the camera turned to the road died within a minute. The rest of the shots in the sequence were done from our production van, or in the backseat with a GoPro on a stick. It was a glorious morning, one of those things I love about production – the ability to trespass lightly with a devoted group of colleagues for the betterment of the project.

Heaven?

Windsor is a development in Vero Beach, Florida designed by Duany Plater-Zyberk, the firm that first designed Seaside. Unlike Seaside, it is private, with much of its 416-acre site given over to a golf course and polo grounds. It represents a fascinating example of smart high density planning that offers privacy to its residents without putting each house off deep in the woods.

Merrill’s Town Center is seven buildings, a semi-circular lawn, gardens. Buildings that both resemble crude Greek temples and the vernacular architecture of St. Augustine, it has an air of serene beauty. Scott Merrill’s son Will was a young boy when he first saw the Town Center. He asked his father, “Are we in heaven?”

Architecture Students in Rosemary Beach

Gregory Delaney’s architecture students from the State University of New York at Buffalo School of Architecture and Planning.

We saw them in Alys Beach and then later on the streets of Rosemary Beach. We were shooting a construction site where one of Merrill’s buildings is coming together, and his Town Hall in Rosemary. These students were always on the edge of our frame. I was surprised. Architectural walking tours are a common site in Rome, sometimes in Chicago, but I didn’t expect to see them along the Gulf Coast. I watched the students sketch and spoke with Delaney. He was working with a book of ground plans of towns and cities around the world, as well as sections of buildings. Merrill’s work was in their book.

I thought it would be fun to get a photo of them and I kept missing it. But while we were sitting down for lunch, they all marched down the street. I leapt up and requested a photo.

They complied.

The New Bali Club

Here are a set of buildings decaying along Old Dixie Highway in Indian River County that captured my imagination.

Merrill drove past it on the way to show us another decaying remnant of local architecture, a grapefruit sorter. We made of point of featuring it prominently because it suggested to me precisely the sort of landscape Merrill would have encountered as a young man criss-crossing the country by car, rail, or foot.

The other intriguing thing about this stretch of road was the number of people who rode up and down it on bicycle. The cyclist here was fast receding by the time I pulled out my iPhone and snapped the picture. But look closely, he’s there.

The Old Dixie Highway is a lot like the roads in William Least Moon’s “Blue Highways,” a book from 1982 chronicling a trip across America on rural backroads. It is home to both derelict remnants of once upon a time and those for whom the bicycle is the most practical and realistic way to get around.

Leaving Florida

When I was doing research for this piece Scott Merrill told me the best book to read on Florida was Michael Grunwald’s The Swamp: The Everglades, Florida and the Politics of Paradise. I was reminded a lot of the interior of Florida, including Walt Disney World and Orlando, home to the airport we flew out of, were wetlands land drained for human habitation and farming. Orlando is at the northern end of the Everglades, which by anyone’s calculation was nearly destroyed by a policy of drainage.

When you drive in from the coast to the airport you are reminded of the fact that you are in the middle of a whole lot of wetlands. And here they built this airport out of the footprint of a World War II military air base, complete with space-age pod-like trams between terminals. None of the palms, by the way, are native. And the face that pops in briefly is Tim Boyd’s. This tram feels like something concurrent with Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, that is an old vision of tomorrow.

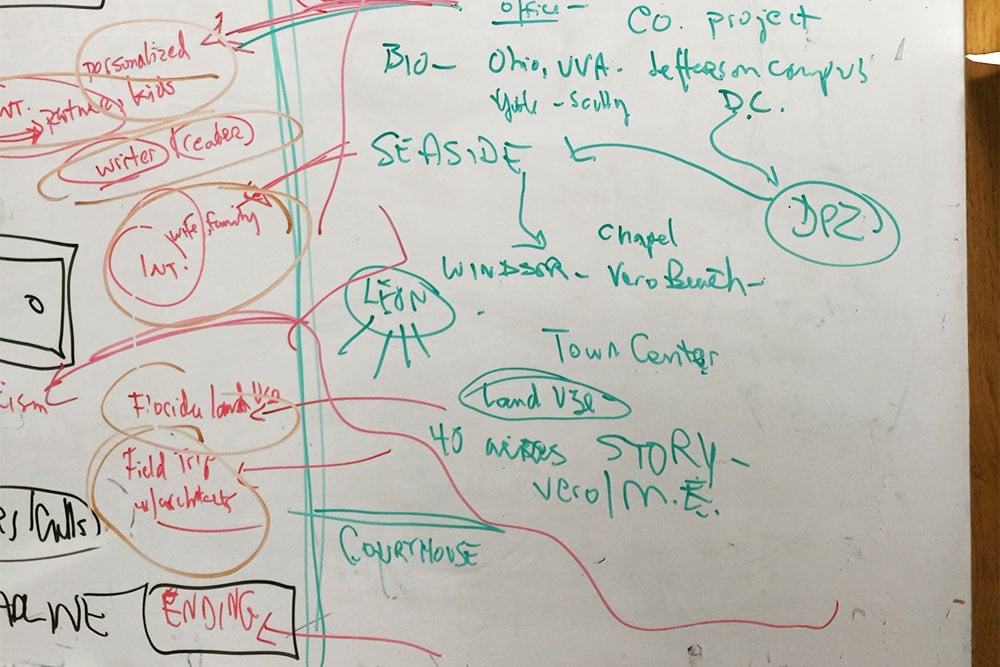

The Whiteboard and the Script

I don’t follow a straight line when writing a script. And in fact, I don’t really think the word “writing” applies accurately to the process of organizing a documentary.

I look for connections and links and attempt to find the line that will lead through the half hour. I do a lot of drawing and writing on my whiteboard – this represents a mid-point assessment of the potential script. The red marker notes are material missing that I felt necessitated a second trip to Florida to do more photography.

It was all aimed at bringing us closer to Scott. As Tim Boyd said to me when he heard my shooting plans: “So we’re not chasing more buildings, we’re chasing the man.” Yes we were.

The most telling note in red is ENDING. We needed one and we found one.