Father Charles Dahm

Father Charles Dahm is a dyed-in-the-wool activist, following in the footsteps of old-school, firebrand Catholic priests. He has never shied away from an opportunity to challenge authority or hesitated to speak his mind. But he says it is always in service of a single goal: bringing about a more just and peaceful world for all, in other words, putting his faith into action.

“I take a principle from Thomas Aquinas that every act is a political act. Even if you don’t do anything, that’s a political act,” he said from his office on South Ashland Avenue in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood, surrounded by images of Cesar Chavez, Oscar Romero, and Rudy Lozano. Since 1986, he has served as pastor or associate pastor of St. Pius V Church, across the street.

“You can stand by and watch things happen, or you can try to make things better,” he said.

He says he’s been arrested during political demonstrations more times than he can count for acts of civil disobedience, such as occupying a senator’s office, blocking doorways in the Federal Building in downtown Chicago, and dyeing the Chicago River red to draw attention to the bloodshed in El Salvador in the ‘80s. Back then, he was a key Midwest organizer for the sanctuary movement and helped shuttle hundreds of Central American refugees through a national underground railroad of sorts to safe havens in the U.S.

And then there was that book…

When Dahm arrived in Chicago as a young priest in the summer of 1973, he found an archdiocese that he says was marred by deep divisions and run by a man who had centralized power. Unbeknownst to Dahm, Cardinal John Cody had also drawn the suspicion of federal prosecutors, who later accused him of diverting millions of dollars from church coffers. Dahm didn’t just criticize Cardinal John Cody in archdiocese meetings; he meticulously documented and published his denouncements. In his 1982 book, Power and Authority in the Catholic Church: Cardinal Cody in Chicago, Dahm detailed the clash between what he saw as Cody’s hierarchical, authoritarian approach and the more democratic approach advocated by many parish priests, going so far as to call the cardinal “arrogant, supercilious, condescending, compulsive, and suspicious.”

The Archdiocese of Chicago declined to comment. But Monsignor Kenneth Velo, who served as assistant chancellor at the Archdiocese under Cody and is now a senior executive at DePaul University, told WTTW that “the late cardinal had problems with many.”

“Chuck Dahm was on the right side of social justice and would have been a thorn in many people’s side,” he added, “but I’ve always had great respect for Chuck Dahm and what he’s done at Saint Pius, in Pilsen and beyond.”

His began his career as an instigator at a young age in suburban Elmhurst, where he grew up.

“I would just organize people to do things,” he said, such as running across railroad tracks just in time to beat an oncoming train. “It was so stupid. If there were things we're not supposed to do, I’d be like ‘Let’s go over there and try it out.’”

But he was always devout. Even as a young boy, his parents never had to wake him up to attend mass. In fact, more often than not, it was his idea to go – even during the week.

Father Chuck entered the Dominican seminary at the age of twenty. He had to break off a relationship with his high school sweetheart to pursue the priesthood.

“I had to say goodbye,” he said. “It was rough, very rough.”

He spent his early years as a Dominican working with university students in the Bolivian city of Cochabamba and later in La Paz, the capital city. He chose the assignment. It was an electrifying time to be working with young idealists in Latin America, he says. In Cuba, Fidel Castro had just taken power and was implementing broad social reforms. Meanwhile, in Bolivia, activists were fighting to restore the gains of that country’s short-lived, 1952 leftist revolution.

“[The Dominicans] were doing social ministry stuff, social justice stuff. And not just…baptizing people and so forth,” he said. “So that really interested me.”

He worked with students. “We had small groups that met, studied, prayed, and we had talks and a lot of political organizing,” explains Dahm. “And we had parties, lots of parties.”

In 1970, a small cadre of Bolivian students began to suspect that the Dominicans were agents of the U.S. government and that Dahm himself was a CIA agent, so the Dominicans called him back to the U.S.

Wanting to develop the tools to better analyze and influence systems of oppression and power, he enrolled in the political science program at the University of Wisconsin in Madison and began work towards his doctorate.

He moved to Chicago in 1973, where he found the subject for his dissertation, which eventually became his book on the power dynamics in the Chicago Archdiocese.

That same year, he was elected to be the promoter of justice and peace for his Dominican province. Rather than work alone, he rallied clergy and women religious from throughout the Chicago area and co-founded the 8th Day Center for Justice. Named after St. Augustine’s belief that humanity is in the “everlasting eighth day” of creation, in which the role of believers is to help usher the world into its intended peaceful and just state, the center worked internationally as well as at home in the United States. They challenged apartheid in South Africa, fought to reduce the proliferation of nuclear weapons in the U.S., and held corporations accountable for union busting, strip mining, discriminatory labor practices, and other human rights violations around the globe.

Father Dahm also became a regional point person for the national sanctuary movement, which at that time was helping thousands of Central American refugees flee violence in Guatemala and El Salvador. He co-founded the Chicago Religious Task Force on Central America, which became the national headquarters for the movement and eventually organized 423 different sanctuary hubs across the United States.

“Our only agenda was to develop the people in a way that would empower them to do more in their communities.”

His radical politics, combined with his criticism of church hierarchy, earned him a reputation in the Chicago Archdiocese.

“Oh, no, I was not popular,” he said. “I’m still not popular with bishops.”

But he spoke Spanish. So after twelve years of full-time, political activism, his provincial Dominican Order moved to assign him a parish. According to Friar Don Goergen, the provincial superior at that time, Cardinal Joseph Bernardin reluctantly accepted their nomination. “We had to persuade him,” he wrote in an email. But they told Bernardin that Dahm was their nominee, and they had faith in him, and if anything went awry, he “would be accountable to us.”

And so, Father Dahm moved to Pilsen and became pastor at St. Pius V.

The Pilsen that Dahm entered in 1986 was very different than the one that exists today. Neighborhood gangs were splintering and battling for territory. Homes were dilapidated and overcrowded, the rental market dominated by slumlords. City services like garbage pick-up and street sweeping were sparse and inconsistent.

“The place was filthy,” Dahm recalls.

Meanwhile, Dahm says he found a prevailing attitude of resignation at St. Pius V. Parishioners tended to hold traditional Catholic beliefs, such as believing that suffering in life is a virtue.

“You have to understand that the Mexican Catholic Church was way behind the Catholic Church in the United States in terms of understanding some progressive concepts,” Dahm explains. “It was a way of getting people, especially the poor, to be resigned and passive, to tell them ‘Don’t worry about sufferings. In fact, it’s going to get you a higher place in Heaven.’”

As pastor of St. Pius V, he got to work challenging these ideas and promoting an incarnational theology, one which sees Jesus’s time on Earth as an affirmation of human dignity and which calls upon believers to cooperate with the Holy Spirit to usher in the kingdom of God on Earth.

That, he says, requires active engagement.

“God wants us to live in peace and in love,” Dahm explains. “He wants us to grow and use our talents, not only for ourselves, but for others…to build the society which itself is permeated by the kingdom of God, [which is] present to the extent that there is justice, peace, and love. How do you do that? We have to get our children to not be killing each other on the streets, for one. And not being individualists but rather be servants of others.”

Raul Raymundo, a lifelong congregant at St. Pius V, said that in 1988, he was 22 years old and was home on a college break when he attended one of his first masses with Father Chuck. He remembers Dahm giving a sermon about a young man who had been shot across the street from the church.

Dahm asked the congregation, “Are we just going to pray that the problem goes away? Or are we going to do something about it?”

“That’s the kind of person that he is,” said Raymundo. “Some people would have approached that situation like, ‘Let’s just pray and ask God for help.’ But he said, ‘We can’t just pray; we have to do. We have to act collectively and put our faith and values into action.”

Dahm asked the congregation, “Are we just going to pray that the problem goes away? Or are we going to do something about it?”

He credits Dahm with reigniting his Catholic faith and helping him make the connection between his religious commitment and his commitment to his community.

He wasn’t the only one. Soon, Dahm formed a social justice committee at St. Pius V, where parishioners gathered to pray, study the Bible, and reflect upon specific challenges in their neighborhood, focusing on how to tackle them in order to create a community based on their values.

He gathered the priests from five other neighborhood congregations and suggested they do the same at their own parishes.

“Our only agenda was to develop the people in a way that would empower them to do more in their communities,” said Dahm. “You have to know your neighbors. You have to join hands with them to address the problems in your streets, whether it’s gangs, trash, bad lighting…We are all about empowering people to build a healthy community.”

In 1990, those six local priests each pledged $5,000 in seed money and sent one representative from each church to formally launch the Catholic Community of Pilsen, a grassroots community organizing and development organization. It soon became The Resurrection Project, and Raul Raymundo, the only college graduate among them, became its leader.

Today, their efforts have grown into a multi-pronged organization that provides affordable housing to more than 844 families, offers loans to new business owners, and helps connect immigrants, homeowners, new entrepreneurs, and others with services and channels for political engagement. They recently expanded their programs to Back of the Yards, Little Village, and the suburb of Melrose Park.

Father Charles Dahm blesses new, affordable homes acquired and rehabbed by The Resurrection Project in Chicago’s Back of the Yards neighborhood in August 2013. Courtesy of Father Charles Dahm, O.P.

“None of us saw how big this could possibly get,” said Dahm.

Dahm has remained involved and on the board, but says he has always felt strongly that the organization should be independent from the churches and the whims of parish priests.

In the meantime, he has continued to take his message of community engagement to the Pilsen community, holding masses to bless areas where violence has taken place and becoming actively involved in or co-founding several other Pilsen-based organizations, including the Chicago Workers’ Collaborative, an advocacy organization for day laborers; San Jose Obrero Mission, an interim shelter for men and women; and Parenting 4 Non-Violence, which helps parents in areas experiencing violence learn effective strategies for keeping their children safe.

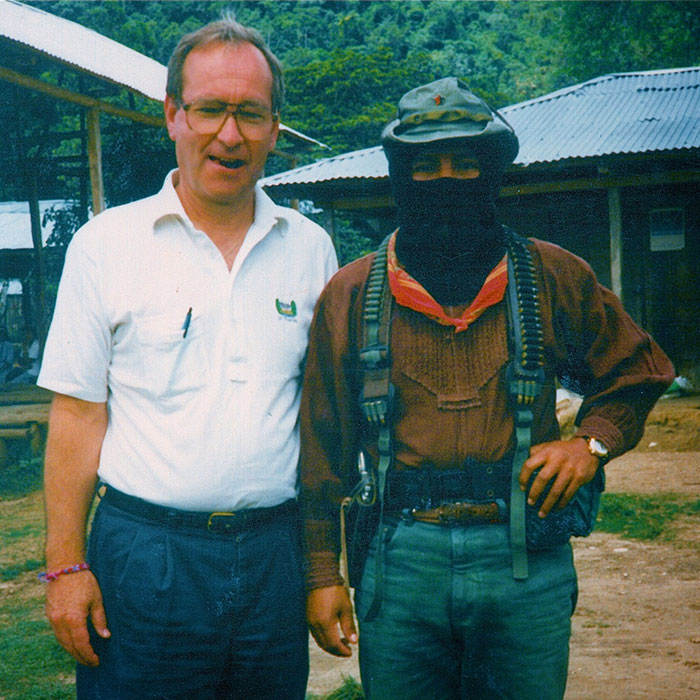

Father Dahm poses with labor and civil rights leader Dolores Huerta at St. Pius V in 1998, officiates mass in the streets of Pilsen circa 1997, and visits with Zapatista Subcomandante Chico in Chiapas, Mexico, in 2002. Courtesy of Father Charles Dahm, O.P.

“You can work on all kinds of levels: your block, your school, your neighborhood, the city...But you live in a universe that impacts you, and you can impact it, and you are called to make a better world,” he said. “So the kingdom of God is all about peace, justice, love, compassion, forgiveness…[I]t’s about putting all these values to work in the society, not just in people’s hearts but in the structures in which we live.”

Much of his work has been identifying, inspiring, and training leaders – at St. Pius and elsewhere – to do that work of challenging structures and empowering people.

One of them is Alma Silva, who has been a member of St. Pius V since shortly after she moved to Pilsen from Mexico more than twenty years ago. Today, Silva is a full-time immigrant rights organizer.

“It’s Father Chuck’s fault,” she says with a smile.

One of the main tenets she says Dahm has helped her understand is the difference between social service, which she considers the more traditional approach to community engagement, and social justice, which requires an element of personal and community empowerment.

“I remember one day in a community meeting, we were discussing homelessness,” she told WTTW. “Father Chuck asked, ‘What can we do for them, aside from just feeding them?’ We discussed the possibility of resources eventually running out. And he said, ‘It is easier to give a starving man a fish than to teach him how to fish.’”

“And this is social justice,” she said. “Social service is giving the man the fish, but social justice tells you that it is better to teach him how to fish. And that way you will never have to worry about him being hungry.”

Over the past decade, Dahm has focused much of his energy on tackling another unpopular topic. He says the church’s position on domestic violence is often misunderstood. Victims are not expected to remain in abusive relationships simply in order to honor their vows. He works to raise awareness of the pervasiveness of the problem and to connect survivors with support, regardless of what they decide to do for themselves and their families.

“We wanted to make faith and religion a support for [a victim’s] leaving [an abusive situation], a strength that comes with knowing God is with you, that God has not abandoned you,” he explained. “What do you think Jesus would tell them? Would he say go back and work it out? Or would he say, ‘Come with me’…He’s a loving and merciful and compassionate guy, and he’s going to protect anybody, right? So that’s what we have to do. It’s a no brainer.”

Working with a social worker at St. Pius V, he has also developed a program that offers individual and group counseling to victims, children, and abusers. Together, they created the largest parish-based domestic violence program in the United States.

Dahm stepped down as head pastor of St. Pius V in 2006 so that he could take what he has learned at St. Pius V and transfer it to other parishes. Since that time, as the first-ever Archdiocesan Director of Domestic Violence Outreach, he has preached about the issue at weekend masses at more than 118 parishes and has helped launch parish domestic violence ministries in 85 of those communities.

“This work is extremely satisfying,” he said. “I get all kinds of comments like, ‘I wish I heard you 30 years ago. I really needed it. Instead, I got a lot of crap from a priest.’ Or ‘Finally, the church is starting to speak about this.’ Or ‘Finally, we get the church to address real issues in the world.’”

He believes social justice issues shouldn’t be sidelined but ought to be at the center of church life. He finds like minds in the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, which takes very specific political positions. They recently criticized President Donald Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accords, opposed efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act, and countered the specifics of Republican-led tax reforms. They have long supported DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, and a host of other measures that would help undocumented immigrants obtain more rights and security.

“I think you’ve got to talk about that kind of stuff [from the pulpit],” he said. “I’m frustrated; I’m disappointed that it doesn’t happen.”

Dahm points to the radical teachings of Jesus as an example for Christian leaders to follow.

“When Jesus turned over the table in the temple, that was a political act. I mean, he was acting against the authorities who were ripping off the people, you know? And using the temple to do it...and they were making money off of it, and he went after these guys. They were the authorities. Many don’t see that as a political act. Well, it was!”

Dahm still encounters apathy and doubt. But he refuses to budge.

“People say, ‘You’re not gonna be able to change things,’” he said. “Well, that’s just not true. We’ve seen all kinds of things change. This neighborhood has improved. People have gotten better jobs. There have been some steps forward. We have made the minimum wage go up. We just passed a law in Illinois that will give more protections to day laborers…It’s miniscule; you can’t see it all the time, but it’s happening….I see change. I mean, the revelations that are happening with sexual assault and sexual harassment, this is progress. This is progress happening.”

Father Chuck Dahm speaks outside a day labor agency during a protest of their treatment of day laborers in May 2013. Courtesy of Father Charles Dahm, O.P.

Father Dahm is no longer on the St. Pius V staff. But he continues to live across the street from the parish and occasionally says mass. People ask him when he’s leaving Pilsen, and he tells them, “Never.”

“I’m dying here. I’m not going anywhere, if I can help it,” he said.

“When I left political activism at 8th Day Center, my colleagues told me you’ll never make it in a parish. ‘You are such a political animal, you’ll be back,’” he said. “And that’s just not true. I mean, I’ve just loved connecting to people and getting involved with their lives.”

Raymundo says it is clear in the way Dahm goes about this work that the pastor is a “people priest.”

“By that, I mean he was very close to people, challenging people, working with people, helping people grow, and helping leaders grow,” he said. “Given his talents, his vocation, he probably could have been in the hierarchy of the church, with more prestige. But I would argue that’s not what has defined him. His focus has always been on being a spiritual mentor and voice of reason and helping people grow, which collectively has helped the parish grow and do more.”

Dahm says that growth has been reciprocal. “I felt, and still feel, totally enriched just living in this neighborhood,” he said. Part of that is the dominant Mexican culture in Pilsen, which he describes as “warm” and “affectionate.”

He’s embraced that culture and wrote a book in 2004, Parish Ministry in a Hispanic Community, to help other non-Hispanic priests learn from his experiences.

Father Charles Dahm receives the Saint John XXIIII Award in recognition of priestly dedication to Hispanic ministry from Cardinal Blase Cupich at the Midwest Conference Center in Northlake, Illinois, in September 2015. Courtesy of Father Charles Dahm, O.P.

He also studied various elements of Mexican culture and created space at St. Pius V for incorporating such traditions as posadas during the Christmas season and ofrendas during Dia de los Muertos.

He even developed a program for teenage girls who want to celebrate their quinceañera, despite the fact that he considers the tradition “anti-feminist.”

But there is one cultural tenet in Pilsen’s largely Mexican community that has always resonated with him and been part of his worldview.

“They have a sense, as all Latinos do throughout Latin America, that they are part of a pueblo. They have a sense of solidarity, of being part of a people, which is so important and which I always say in the church, from the pulpit.”

“Somos un pueblo, pues.”

We are one people.