Raul Hernandez

Judy’s parents weren’t thrilled when she started dating a migrant farm worker who spoke only five words of English.

She met him at the Crystal Fountain, a drive-thru restaurant in rural Blanchard, Michigan, where she waited tables the summer after her senior year in high school.

“They warned me that he was only here for a few months,” she says. “They didn’t want to see me to get hurt.”

It’s true that he was just passing through. He was gone that next fall, headed to Chicago in search of a better-paying job.

Now, forty-eight years later, neither remembers exactly how it all began.

“He was pretty cute,” says Judy, shaking her head. “But, now, I’m like, ‘How in the heck would that happen?’”

But she knows at least part of the answer: Raul Hernandez has an abundance of charm, self-confidence, and, more than anything, determination.

In many ways, it has been the driving force in his life.

Raul Hernandez is one of the co-founders of The Resurrection Project, an organization that has been at the forefront of Pilsen’s transformation through dogged, collective effort over the past 27 years – from an undesirable, under-resourced, high-crime neighborhood to one of Chicago’s most well-organized and thriving communities.

In the fall of 1969, months after they met, Judy enrolled in nursing school. Raul, meanwhile, found a job with Republic Steel on Chicago’s Southeast Side.

As a Catholic school kid growing up in San Luis Potosi, Mexico, Hernandez was forced to learn Latin. His studies served him well; one day at the mill, co-workers noticed that he recognized certain metallurgy terms. They wondered if he was some sort of chemical engineer back in Mexico.

“I didn’t agree, but I didn’t say no,” he says, laughing. “I just went along with it.”

The rumor spread and he quickly moved up the ranks.

Back in Michigan, Judy wrote faithfully to Raul, and he enlisted bilingual friends to translate her letters. They gave him all the encouragement he needed.

That following summer, Raul Hernandez went back to Michigan and proposed.

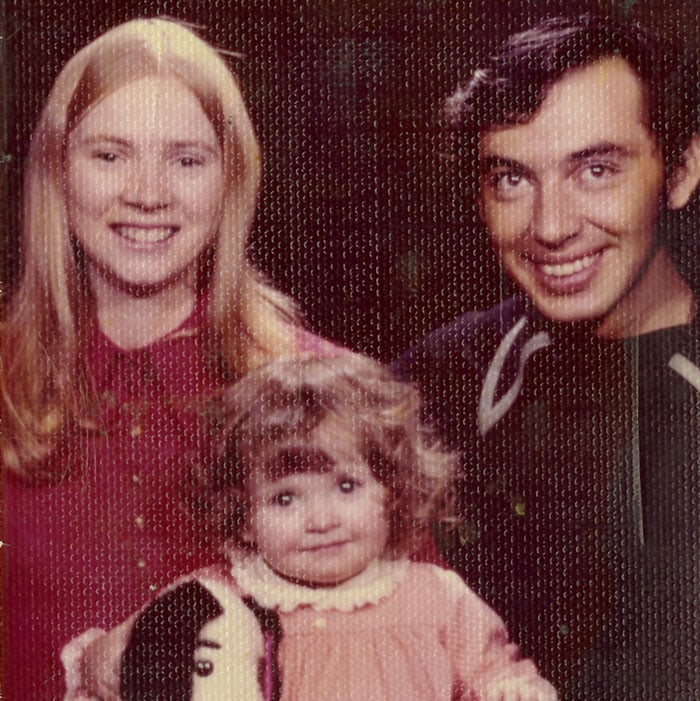

Raul Hernandez with his wife, Judy, and eldest daughter, Tina. Courtesy of the Hernandez Family

After their wedding, the young couple moved to Pilsen, a neighborhood that had a minority, but growing, Mexican population. Hernandez’s mother soon joined them from Texas. Their first daughter, Tina, was born within the year, and another child arrived in 1974. They bought their home at 1815 17th Street in 1975.

Two more children followed and the years rolled by.

Life was good, but it wasn’t easy. Pilsen is one of the oldest neighborhoods in the city – with sections that escaped the Chicago Fire – and the housing stock was old and dilapidated.

City services were scarce. Garbage would pile up in the alleyways, attracting rodents and bugs. The stench was overwhelming in the summer.

Garbage piled in the alleyways. Courtesy of the Hernandez Family

Gang violence was rampant. According to a 1988 article in the Tribune, there were 21 different gangs vying for turf along 18th Street between Des Plaines and Western.

“The Saints, the Disciples, La Raza, the Bishops…They were always killing each other,” says Hernandez.

And there seemed to be little anyone could do about it. The old-guard aldermen were indifferent to the needs of their growing Latino constituency.

Some of their neighbors were downright hostile. In the ’70s and ’80s, Pilsen was still a divided neighborhood, with longtime Bohemian residents leery of the Latino newcomers. White flight contributed to the rapidly shifting ethnic makeup of the neighborhood and to the anxiety of many Bohemian old-timers. Whites and Latinos frequented different stores and attended separate masses.

“Polish people would walk on one side of the street and Mexicans on the other side,” says Hernandez.

His eldest, Tina, often asked if they could just leave Pilsen and move to a neighborhood that wasn’t so unwelcoming, violent, and rundown.

“I used to tell her, when you have a problem, you don’t run. You’ve got to solve the problem. If we start running, we’re never going to stop.”

“I used to tell her, when you have a problem, you don’t run. You’ve got to solve the problem. If we start running, we’re never going to stop,” he says.

One day, in the late 1980s, a progressive priest from a local parish knocked on the door. Father Jim Kaczorowski of St. Adalbert’s knew Hernandez’s mother well. She regaled him with stories of Raul’s fight to organize the Mexican workers at Republic Steel.

Father Kaczorowski asked Hernandez if he could come to the rectory to help him with something the following night.

“I thought he needed my help to move some furniture or something,” says Hernandez. “I didn’t think anything else.”

When he got to the rectory, there were approximately fifteen Polish parishioners sitting in a circle.

“This is your meeting,” Father Jim said to Hernandez. He wanted Hernandez, now bilingual, to help him build a bridge between the Eastern European and Latino communities.

“I’m not gonna lie,” says Hernandez. “It started off a little awkward.”

But before long, they found they had a lot in common. They wanted better schools, less crime, and more responsive landlords. Soon, Hernandez was also coordinating conversations between the parishioners at St. Adalbert’s and other neighborhood churches.

At approximately the same time, the pastors at six local churches, headed up by Father Charles Dahm, co-founder of the progressive Eighth Day Center for Justice, were discussing ways to organize and empower the local community. The pastors of the other five churches – St. Procopius, Holy Trinity, Providence of God, St. Vitus, and St. Adalbert -- each contributed one representative and $5,000. They used the money to hire a local community organizer, Mike Loftin.

Father Dahm says that he had one mission: “to develop the people in a way that would empower them to do more in their communities.”

"I don’t think any of us saw how big this could possibly get, but we certainly saw that we were going to have to do this on our own. We had to start an organization."

“I don’t think any of us saw how big this could possibly get, but we certainly saw that we were going to have to do this on our own. We had to start an organization.”

Representatives from each of the churches started knocking on doors – first within their own networks and then to people referred to them.

“You tell them a little bit about yourself and try to learn about them: what their ambitions are, what their needs are, what they are willing to do to get the things done,” explains Hernandez.

The interviews gave the team a clearer sense of the priorities of the community, as well as a strong network of people with a stake in the organization and an inventory of their skills.

Most of the people were most concerned about gang violence at that time. But Loftin was afraid that it was too difficult to achieve.

“Groups at UIC and the police had been working on it for years, but they never accomplish[ed] anything,” says Hernandez.

To avoid defeatism among their members, Loftin urged the coalition to identify a winnable issue. They landed on trash pick-up – one of the most visible and pervasive problems in the neighborhood. Hernandez estimates that Streets and Sanitation came about once a month at that time.

“The garbage would pile up in the alley so bad, sometimes you couldn’t even walk back there,” says Hernandez, “especially in the summer, when the smell would be horrible.”

They wanted to double that, to two pick-ups per month.

The coalition, then calling itself the Catholic Community of Pilsen, or CCP, invited a representative from Streets and Sanitation to meet with them.

The victory gave the new coalition momentum, and they began planning their next campaign. Pilsen’s housing stock was a picture of neglect: vacant lots strewn with garbage and old furniture, known gang houses, and rundown housing with peeling lead paint, no heat, and broken locks.

Mayor Richard M. Daley had recently launched a program, New Homes for Chicago, aimed at reassigning ownership of city lots to community organizations to develop as new affordable homes.

It could be just the opening they needed.

“That was something you could see. You could measure success,” said Hernandez. “We decided that was the way we wanted to go.”

They began taking an inventory and targeting blocks in need of improvement.

Then, in 1990, they invited Daley to St. Procopius and packed the sanctuary with nearly 800 people.

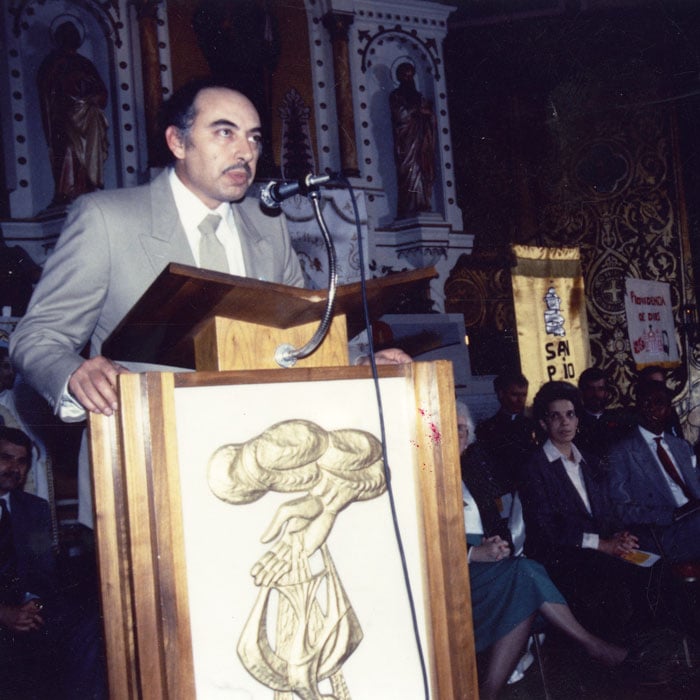

Raul Hernandez speaking at St. Procopius Church. Courtesy of the Hernandez Family

Hernandez got up and explained the problem. He asked Daley for two dozen lots.

“I said it in Spanish and then in English,” Hernandez explains. “When I started saying it in English, you could see Daley [squirming in his seat].”

But Daley acquiesced.

“A politician is never going to say ‘no’ in front of a big crowd,” says Hernandez.

Afterward, when Daley shook Hernandez’s hand, he wasn’t happy. Hernandez says he muttered under his breath, “‘Don’t you ever do that shit again. I don’t like to be ambushed.’”

Nevertheless, they eventually got their lots.

And they got to work.

To expand on such a grand scale, the coalition of church members needed some help. So they started building alliances.

They reached out to a civic-minded developer, Barry Bigelow, who walked them through the process of applying for permits, hiring contractors and architects, and navigating city building codes.

They established a relationship with Northern Trust to secure low-interest loans for potential home buyers, as well as current homeowners who were willing to fix up their properties.

They created a partnership with Neighborhood Housing Services of Chicago, a nonprofit that trained dozens of CCP leaders so that they could counsel interested community members on building credit, budgeting, and applying for a mortgage.

Last but not least, they continued reaching out to community members – not through email blasts or hanging up flyers, but by knocking on doors. Lots and lots of doors.

“Word of mouth is such a better tool,” says Hernandez.

He says personal relationships were a key to their success, as was the support of the churches, which gave them not only legitimacy but a built-in audience for their appeals.

“They [gave] us the opportunity to use the pulpit to talk to the people, and you know, it just gives you a little bit more trust from the people when you’re talking from the pulpit,” he said.

The churches also helped them out financially.

For example, the Mercy Sisters of Chicago loaned the CCP more than $280,000 to help the organization build a line of credit for construction financing.

In the end, 105 families were pre-qualified for mortgages. But they ran into a problem: they had only 24 homes.

Hernandez says they felt that they were in a jam. Their efforts in financial literacy and counseling had been almost too successful. Now they risked turning their supporters against them.

“You wake up expectations in the people and then how are you going to tell them, ‘Sorry, you’re not going to get it’? They were pre-qualified. How are you going to tell them no? ” says Hernandez.

Father Jim suggested they hold a raffle.

But Hernandez was afraid that the stakes were too high. People would think it was rigged.

So Father Jim invited Cardinal Bernardin to pick the winners.

When the day of the raffle finally arrived on Tuesday, September 3, 1991, Hernandez says he was “very, very nervous.”

But when he got to the church, the mood was electric.

Winners were announced to waves of applause and hugs and tears. Antonio and Angela Morales. Abelina and Rosa Garcia. Roberto and Carmen Mejia.

It was not just a relief, says Hernandez. It was a triumph.

“The people were so happy. It was like too many victories in the same event,” he said.

And then the real work began. What started as a small band of community organizers now had their work cut out for them. They needed to construct 24 homes.

They asked the archdiocese if they could purchase the recently shuttered St. Vitus to use as an office space. But the bishop at the time said they would need to charge them $300,000.

So they went directly to Cardinal Bernardin.

“He wanted to know what our plans were for the property. We told him, specifically. We wanted to open a daycare and we wanted to do financial literacy,” says Hernandez. “He asked us how much we wanted to pay for it and Raymundo said, ‘One dollar.’”

“Bernardin said that they were going to have to get something for it.”

“He sat and thought and finally he said, ‘How about ten dollars?’”

The CCP membership helped them clean out and transform the building. The additional space allowed them to expand their involvement in the community.

A few years later, now operating as The Resurrection Project (TRP), they were able to open a sliding-scale daycare center, which served 180 Pilsen children and created 22 jobs in the community. They took what they learned in setting up the daycare center and shared it with other members of the community interested in opening in-home daycare.

After struggling to find qualified contractors to build those first 24 homes, they also created a construction cooperative. Even though many Pilsen residents had the know-how, they often lacked the required insurance, union membership, or license for large-scale, city-supported projects. They held workshops on bidding on large, city-financed projects and applying for permits. The cooperative helped carpenters and contractors not only share skills but helped build a network and a pathway into union membership.

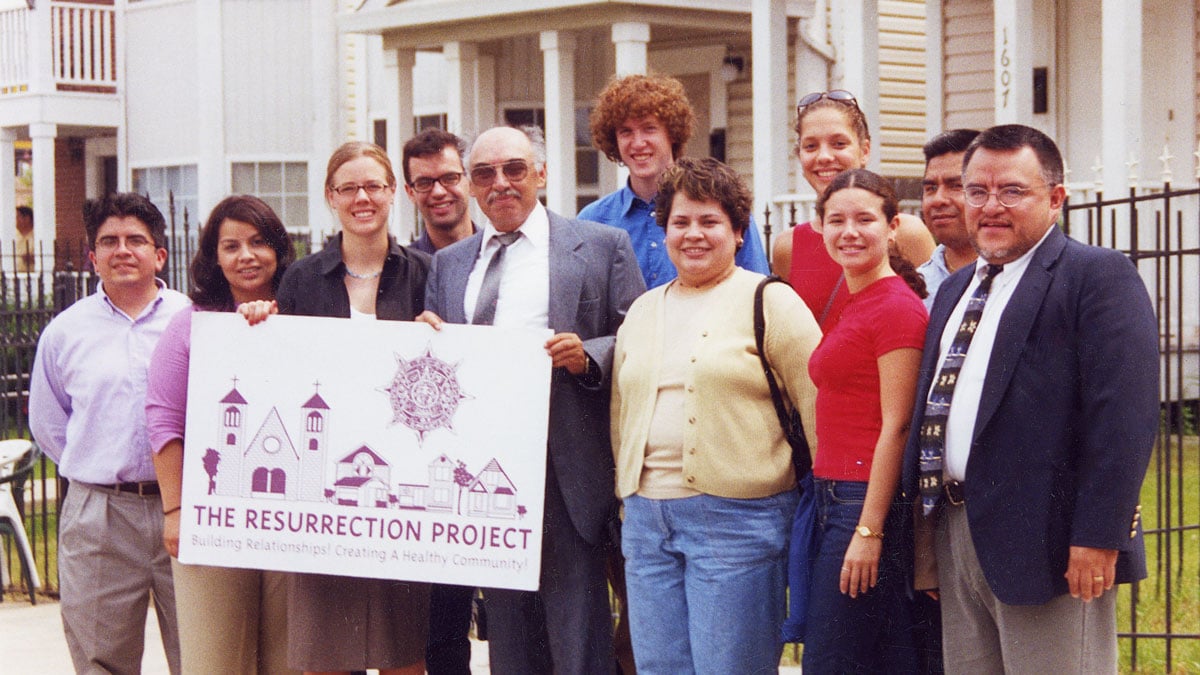

The Resurrection Project team stands in front of the new houses on Throop. Courtesy of the Hernandez Family

But it was what happened in 1993 that really put TRP on the map.

After some additional organizing and the successful construction of their first homes, they convinced Mayor Richard M. Daley to grant them an additional 100 lots and $2 million in city subsidies. With the money, they were able to reduce the costs to the home buyer so that the new houses ranged in price from $69,000 to $109,000. On the higher end of the scale were two-flats and a small number of five-bedroom homes, designed to entice moderate-income buyers to stay in what was then still a struggling community.

The lottery for the additional 100 homes was held in September of that year. A Chicago Tribune reporter described the scene, or “what may have been the largest lottery held in the city for affordable housing,” as filled with “thundering applause” and “shrieks of joy.” One woman was so overwhelmed, she reportedly needed help getting up from her seat after her name was called.

To distribute the investment through a wider swath of the neighborhood, the organization scattered their lot requests throughout Pilsen.

Raul Hernandez says that increasing home ownership rates has been the key to transforming the community.

"When you build a house, you build a community."

“We like to say that when you build a house, you build a community,” he explained. “When you buy a house, you’re buying part of the community. You’re buying the problems and the advantages that come with it. It’s all something you have to support and maintain. You’re more concerned about the problems around you, the education…You have an investment in all of it.”

Affordable Homes Created in Pilsen by The Resurrection Project (1992-2017)

They began targeting drug houses and working to acquire and, at times, demolish structures that were magnets for criminal activity. In the mid-’90s, Hernandez, his neighbors, and TRP pressured the city to tear down abandoned silos just a couple of blocks from his house. The site was called the “shooting range,” not because of violence, per se, but because of the drug activity that took place there.

The community of Pilsen has changed dramatically since that time, and TRP, with Raul Hernandez now on the board, continues to be a driving force behind those changes. They’ve expanded into the affordable rental market and opened a center for senior housing, as well as a new home for undocumented students, many of whom are unable to access traditional loans. They’ve supported other neighborhood nonprofits, such as Instituto del Progreso Latino, helping them obtain new facilities and leverage the needed tools to save money on those investments. They’ve expanded beyond financial and housing services to create after-school programs, immigration services, and small business support. They’ve been recognized locally and across the country for their innovative approach and impact.

And they are taking everything they learned in Pilsen and working to replicate their success in other neighborhoods – including Little Village, Back of the Yards, and Melrose Park.

“We now have to have a map for them to follow,” says Hernandez.

But their success has come with a downside: new construction is no longer the result of subsidized, community-driven initiatives. Today, Pilsen development is big business.

“In a way, we put ourselves out of the market in Pilsen,” says Hernandez. “We cannot compete. We cannot do it.”

Today, TRP fights to preserve the neighborhood’s affordability through working with the local alderman to ensure that any new, large-scale housing developments in the ward set aside 21 percent of their units as affordable housing.

Hernandez retired from the steel mills in 2002. His children are now grown, and they’ve had children of their own.

Left: Raul Hernandez stands in front of his living room wall covered in family photos.

Right: Hernandez plays with his youngest grandson. Photos by Kaitlynn Scannell

Their son, Raul Jr., and his wife live a few blocks away, with their son, Raul III. They are expecting another child this summer.

Their daughter, Erica, lives next door with her husband and son.

And Tina, the one who always wanted to leave Pilsen as a child, moved to Park Forest in her early twenties but returned eight years ago to raise her own children.

She says that things are different for them – there is less violence and more opportunity. Her daughter is in eighth grade and next year she’ll go to Whitney Young, one of Chicago’s top high schools.

“The improvements are obvious,” she said. “And I think TRP has a lot if not everything to do with that. They’ve made it better.”

Today, they live in the house across the street from Raul and Judy.

“I definitely never want to leave Pilsen again,” she said.

– Jessica Pupovac