The Tenement

The Tenement

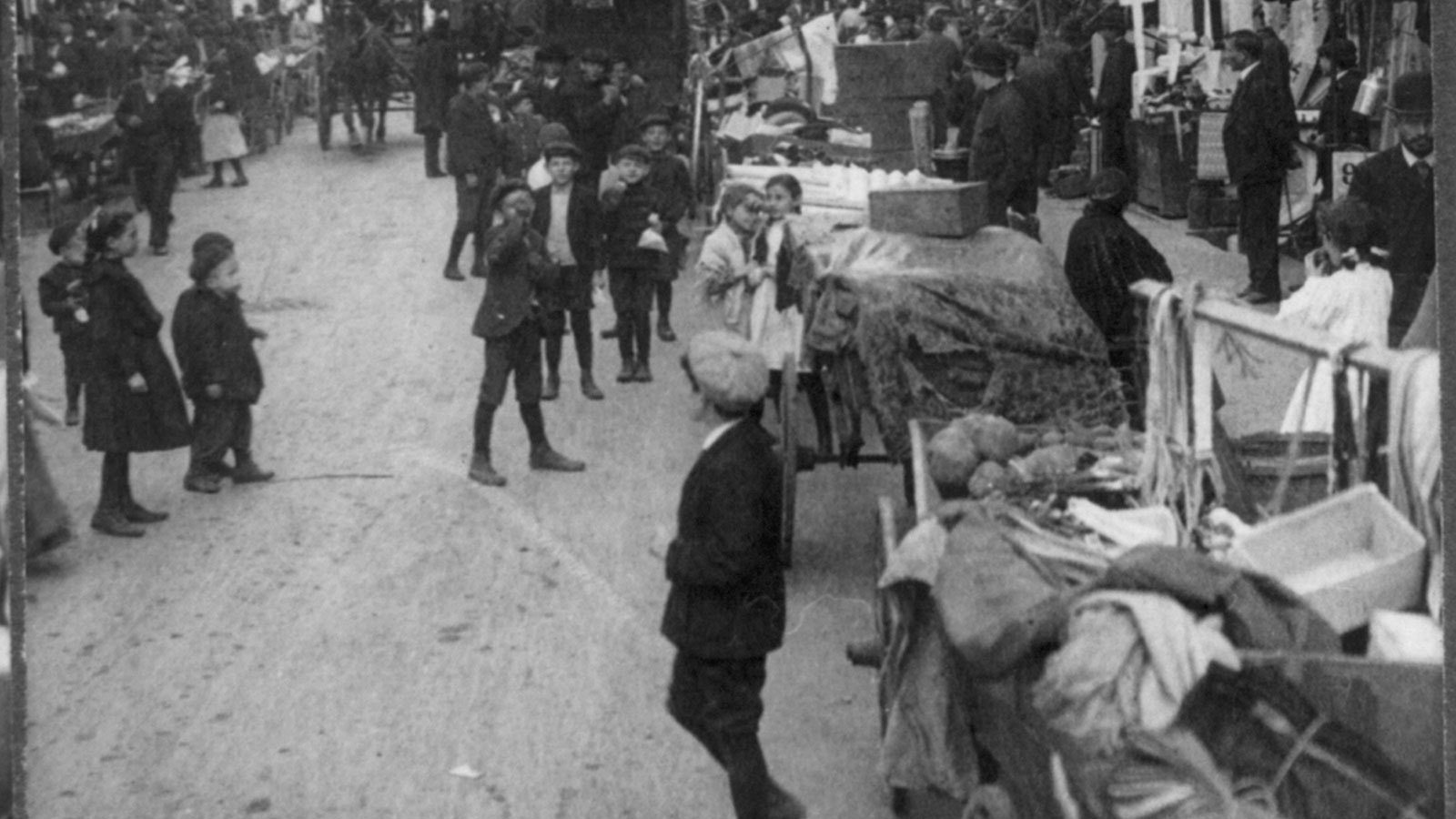

In the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution spawned opportunity in America's cities. Waves of immigrants from Poland, Germany, Ireland, and beyond joined migrants from America's countryside, swelling urban populations. In New York City, the population grew more than 50-fold during the century - increasing from 79,000 in 1800 to more than 3.4 million by 1900.

Watch the Segment

With these massive waves of newcomers came a major housing challenge for cities. With too many people and too little space, something had to give.

Thus was born the American tenement: narrow buildings, typically five to seven stories tall and with a footprint of 25 by 100 feet, carved into apartment units of approximately 350 square feet each. The crowded buildings solved the housing supply problem, but often provided abysmal living conditions, with little natural light, poor ventilation, and no indoor plumbing.

Web Exclusive Video

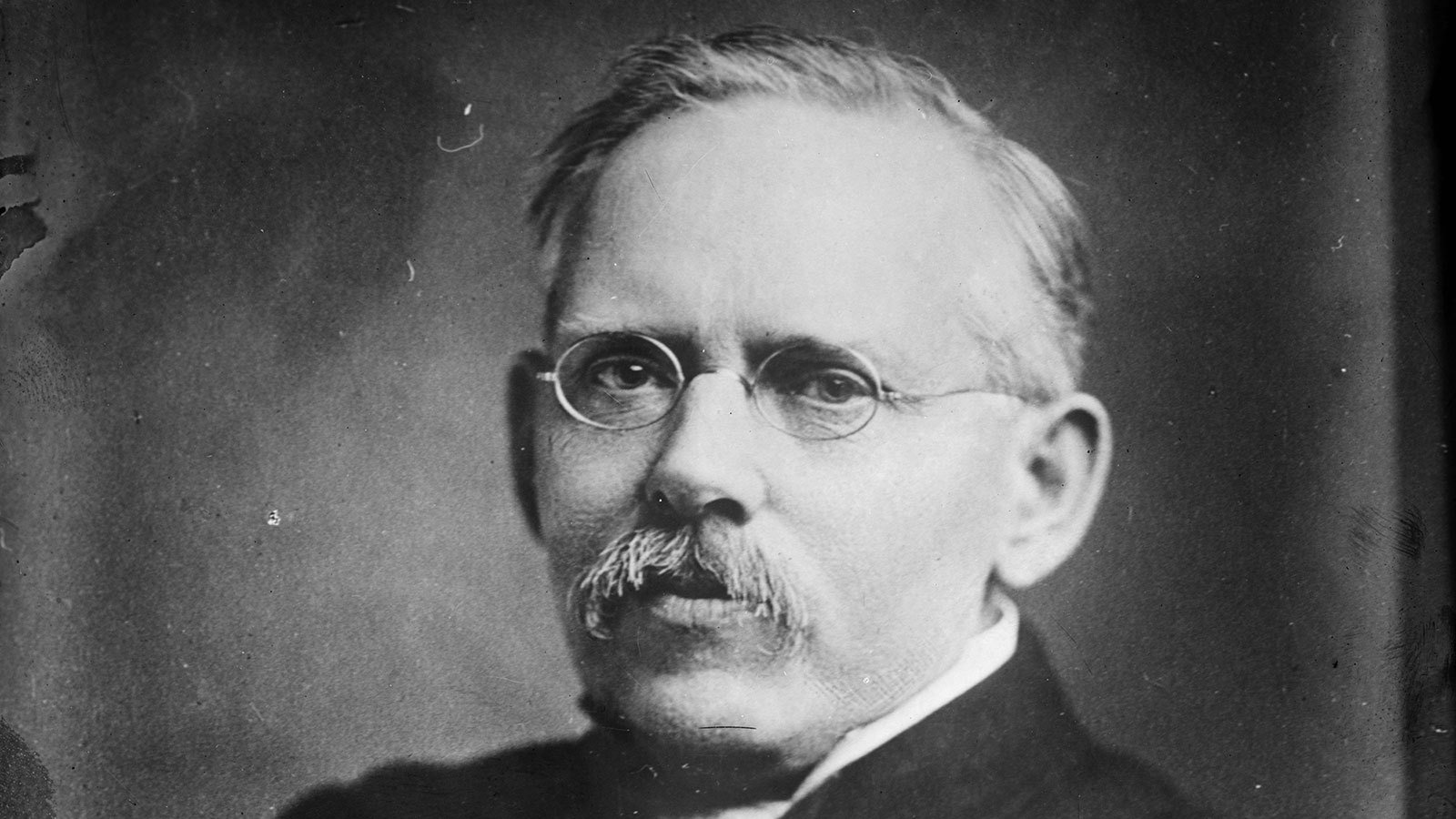

These conditions attracted the attention of social reformers, including journalist and photographer Jacob Riis, who documented them in How the Other Half Lives. This work of muckraking photojournalism described tenements as "ugly barracks" with "rotten floors" and "poorly patched roofs." Riis blamed profiteering landlords for conspiring "to shelter at as little outlay as possible, the greatest crowds out of which rent could be wrung."

Jane Addams cited tenement conditions in Chicago:

A woman's simplest duty, one would say, is to keep her house clean and wholesome and to feed her children properly. Yet if she lives in a tenement house, as so many of my neighbors do ... her basement will not be dry, her stairways will not be fireproof, her house will not be provided with sufficient windows to give light and air, nor will it be equipped with sanitary plumbing, unless the Public Works Department sends inspectors who constantly insist that these elementary decencies be provided.

As the plight of tenement dwellers came to public attention, reforms eventually took place, including requirements that landlords install fire escapes, indoor plumbing, and gas lighting to make hallways safer.

Today, you can experience tenement life at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum in Manhattan, where living conditions have been preserved as they were in the 19th century.

Learn More

- Explore the Tenement Museum site.

- Read Jacob Riis's description of tenement life.

- Play a simulation game to see what immigrant life was like.