The (Im)Perfect Crime

Daniel Hautzinger

October 31, 2017

Genius IQs, wealth, dashing good looks, respected families – and an arrogant desire to commit the perfect crime. Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb had everything going for them when they kidnapped and murdered a fourteen-year-old boy simply to prove they could. Despite their utter confidence, they were caught and confessed within ten days of the murder, leading to a highly publicized trial that became a referendum on justice and capital punishment as the eminent social crusader Clarence Darrow fought to save the pair from the death sentence.

Dubbed the “crime of the century,” Leopold and Loeb’s coldblooded act captivated the nation as surely as did the killings of Chicago’s first infamous murderer, H. H. Holmes, three decades earlier. As with Holmes, the motives of Leopold and Loeb were murky. But unlike with their predecessor, there was an explanation offered, involving feelings of superiority, a wicked sexual pact, and malformed psychologies. How were two brilliant teenagers led to commit a heinous act?

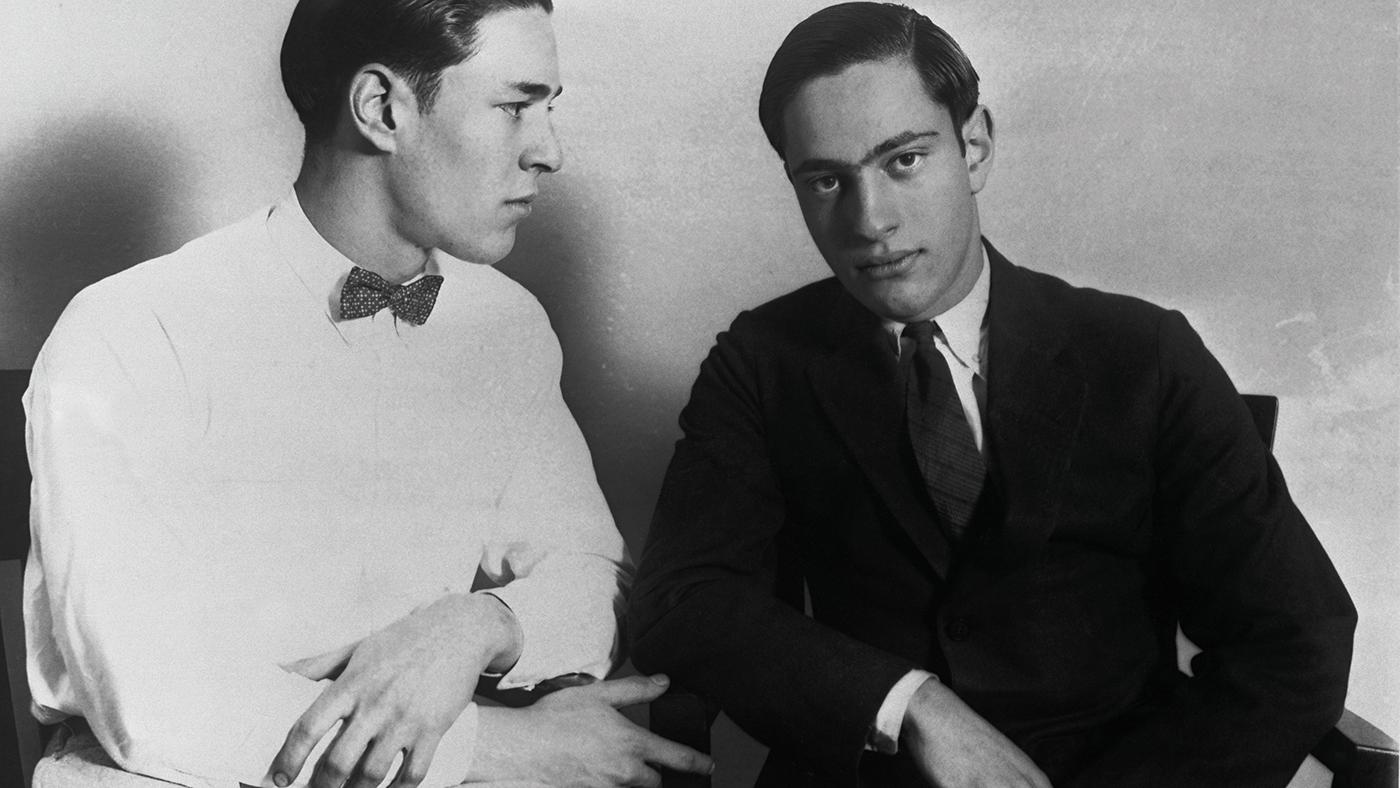

Leopold and Loeb considered a number of victims before settling on Bobby Franks. Image: Courtesy of Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago LibraryLeopold and Loeb were cut from the same cloth, although they were a mismatched pair. They grew up in the privileged, cloistered world of Kenwood, a neighborhood of mansions and tennis courts populated by successful Jewish families and scholars at the nearby University of Chicago. The Leopolds had a fortune of a million dollars; the Loebs, four million. Loeb graduated from high school at 15, while Leopold spoke fifteen languages by the time he was 18, five of them fluently. But where Loeb was a dazzling socializer whose handsomeness inured him to any crowd, Leopold was more reserved and awkward, a bird-lover with a poetic bent.

Leopold and Loeb considered a number of victims before settling on Bobby Franks. Image: Courtesy of Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago LibraryLeopold and Loeb were cut from the same cloth, although they were a mismatched pair. They grew up in the privileged, cloistered world of Kenwood, a neighborhood of mansions and tennis courts populated by successful Jewish families and scholars at the nearby University of Chicago. The Leopolds had a fortune of a million dollars; the Loebs, four million. Loeb graduated from high school at 15, while Leopold spoke fifteen languages by the time he was 18, five of them fluently. But where Loeb was a dazzling socializer whose handsomeness inured him to any crowd, Leopold was more reserved and awkward, a bird-lover with a poetic bent.

The pair had been friends for about two years when they began committing petty crimes for sheer excitement – they certainly didn’t need the money they stole. Within a year, they had decided to commit the “perfect crime” both for the thrill and to prove their superiority: Leopold had read Friedrich Nietzsche and decided that he and Loeb embodied the philosopher’s idea of the Übermensch, or “super-man,” who was literally “above man.”

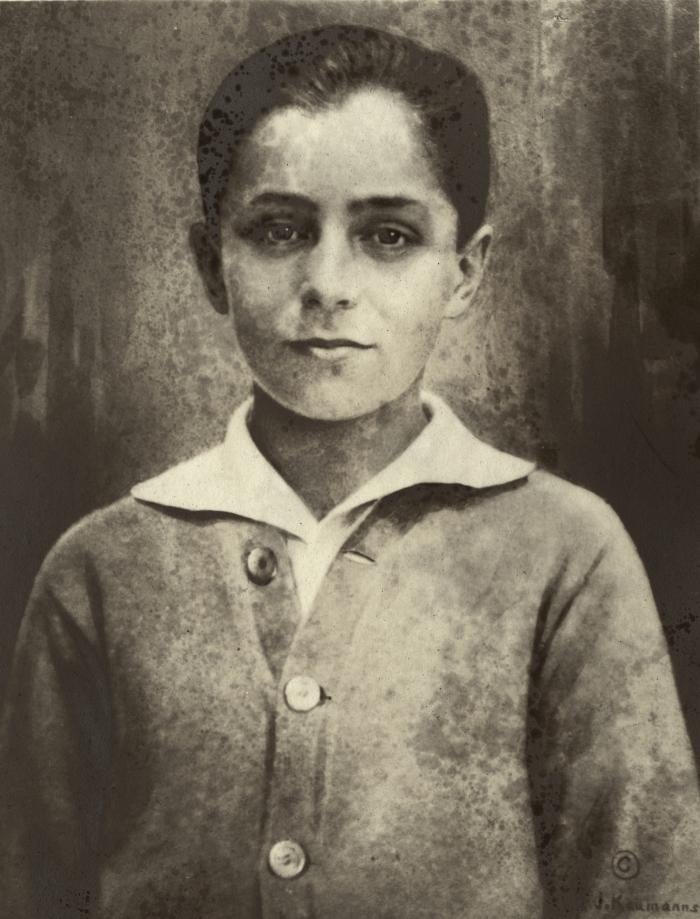

They carefully planned out a kidnapping and murder, and began to contemplate victims. Deciding it would be easiest if the person knew them so that he wouldn’t hesitate to get in a car with the two young men, they considered Loeb’s brother as well as a close friend – the idea of being his pallbearers titillated them – before settling on the first boy they saw walking alone.

On May 21, 1924, they cruised around Kenwood in a rented car before picking up Bobby Franks, a distant cousin of Loeb. As Leopold drove with Franks in the front seat, Loeb grabbed the boy from the back and smashed his head with a chisel. The idea was to knock him out and kill him later, but Franks remained conscious. As the boy struggled, his head streaming with blood, Loeb stuffed a cloth in his mouth and suffocated him.

Leopold and Loeb stopped for a calm dinner, then proceeded to the marshes on the far southeast side of Chicago, near the Indiana border. After disfiguring the boy with acid and stripping him of his clothes, they stashed his body in a culvert. They called the Franks that night to inform them of the kidnapping, then sent them a typed ransom letter the next day demanding $10,000 and promising that Bobby was still alive.

Despite their self-assured cleverness, Leopold and Loeb’s plan quickly started to unravel. A worker found Bobby’s body the day after it was dumped, as well as a pair of glasses. A relative of the Franks identified the corpse immediately, foiling the attempt at ransom money. As reporters swarmed over roiling Kenwood, Loeb arrogantly offered to help find the killer, even telling one journalist that if he were to murder a boy, it would be “a cocky little son of a bitch” like Franks.

One simple clue led the police to Leopold and Loeb, though they still needed more evidence. Photo: Chicago History Museum

One simple clue led the police to Leopold and Loeb, though they still needed more evidence. Photo: Chicago History Museum

Nine days after the murder, police discovered that the glasses had a unique hinge that was only sold at one location in Chicago. Only three pairs like it had been purchased, one by Leopold. He was brought in for questioning but insisted that he had been joy-riding with Loeb at the time, and that he often went bird-watching in the marshes; he had simply lost his glasses there. Loeb corroborated the alibi. Even after an expert hired by a reporter determined that the ransom letter and typed study notes from Leopold were written on the same typewriter, the police lacked the evidence to pin the crime on him: they couldn’t find the typewriter.

But then the chauffeur for the Leopolds sealed the case in an attempt to save the young men. They couldn’t have kidnapped Franks because they didn’t have a car, the chaffeur said; he had been working on Leopold’s all day. The only problem was that the pair had said in their alibi that they were joy-riding in the very same vehicle that the chauffeur was working on. Faced with the mounting evidence, Loeb cracked and confessed; Leopold quickly followed.

Loeb’s uncle approached Clarence Darrow, who had gained a reputation as a social rights-defending lawyer from his work with unions, to defend Leopold and Loeb. After initially refusing, Darrow reconsidered when he realized that the massive publicity of the case would help him make a stand against capital punishment.

The trial opened on July 1. Right at the outset, Darrow reversed his clients’ plea of not guilty – now their punishment would be left to the Judge John R. Caverly alone rather than a jury. Darrow – who found his clients cocky – built his defense on a new kind of testimony: that of psychiatric experts, then called alienists, who plumbed the depths of Leopold and Loeb’s childhoods, dreams, and lives, and used Freudian analysis to explain their attraction to crime. (Such detailed examination of the defendants’ lives also helped the public, who were avidly following the trial in the daily papers, come to see the murderers as human.) How else could you explain why two promising young men with no concrete motivation turned to crime?

Clarence Darrow (right) found his clients cocky but saw an opportunity for publicity against capital punishment. Photo: Chicago History Museum

Clarence Darrow (right) found his clients cocky but saw an opportunity for publicity against capital punishment. Photo: Chicago History Museum

Well, there was also the strange pact between Leopold and Loeb. It seems that, on certain days, Loeb would have sex with Leopold if Leopold would commit a crime with Loeb. That’s not to say that Loeb was not interested in sex or that Leopold didn’t get off on crime; rather, the two seem to have fed off each other’s predominant desires.

Darrow’s twelve-hour closing remarks, delivered over three days, are legendary, considered one of the greatest examples of eloquence in American legal history. After nineteen days of deliberation, Caverly announced that Darrow’s psychological experts had not swayed him. But because of the defendants’ ages – 18 and 19 – he would not sentence them to death. Instead, they received a life sentence for murder, plus 99 years for kidnapping.

Watch Jay Shefsky try to unravel a nagging mystery related to the Leopold and Loeb case: what happened to Leopold's excellent and extensive bird collection?

For the first seven years of their confinement, Leopold and Loeb were kept separated. Once they were again allowed contact, they started a correspondence school for their fellow prisoners. But in 1936, an inmate slashed Loeb with a razor. The story went that Loeb propositioned the other man, enraging him, but that account is probably false. Either way, Loeb died in the infirmary with Leopold standing distraught at his side. Although Leopold later claimed in a memoir that Loeb was the mastermind of the murder and forced him into it, his emotional writing at Loeb’s death suggests that he was deeply attached to his partner in crime and willingly collaborated with him on their devilish plan.

Leopold was a model prisoner, setting up a library, teaching inmates, and becoming an x-ray technician while serving out his sentence. After being denied parole in 1953, he was released in 1958. He moved to Puerto Rico to work as a medical technician and married a Puerto Rican widow in 1961. Nathan Leopold died in 1971, 35 years after the death of his beloved companion and 47 years after they murdered a fellow teenage boy for almost no reason at all.