The Father of Black History

Daniel Hautzinger

February 1, 2018

This story was originally published in 2018.

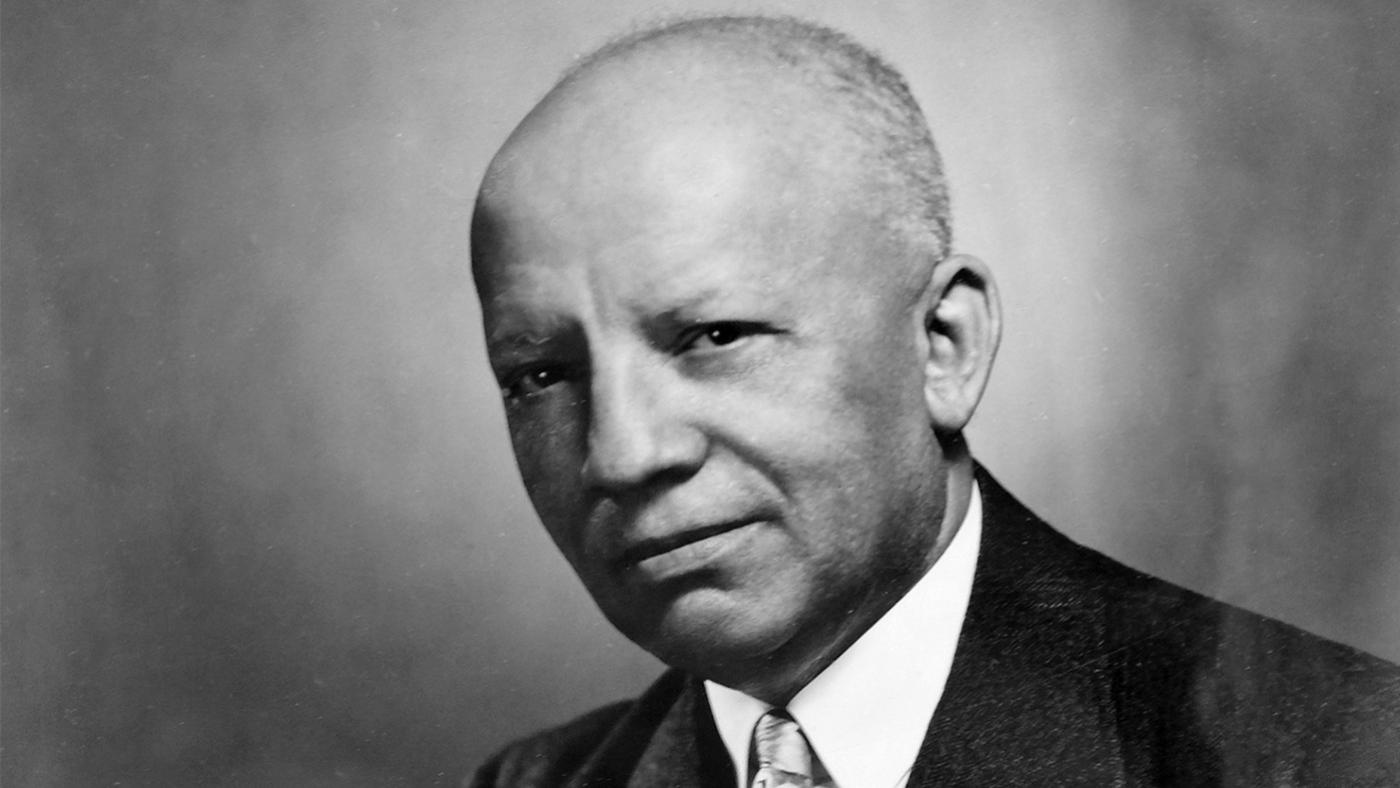

If you go to the Google search page today, you’ll see a doodle of a distinguished gentleman writing at a desk in front of shelves of hefty tomes, pages flying from his notebook filled with illustrations come to life of celebrated African American figures: Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, a jazz musician. The scholarly gentleman animating these icons is Carter G. Woodson, the “father of black history” who inspired the designation of February as Black History Month. (Today is also the birthday of Langston Hughes, who briefly worked as an assistant to Woodson when the budding poet was in his early twenties.)

Woodson was born to freed slaves in 1875 and quickly proved himself an outstanding student. His studies were continually delayed by the need to earn a living, but he devoted himself to learning and self-education. He eventually earned a degree from Berea College in Kentucky, a bachelor’s and master’s from the University of Chicago, and a PhD from Harvard, making him the second African American to earn a doctorate from that hallowed institution, after W.E.B. Du Bois, whom he later befriended. Woodson eventually became a professor and later a dean at Howard University.

Dismayed by the lack of knowledge and research around African American history – American history was told by and about white people, and African Americans were presented as having very little history beyond that of slavery – Woodson made it his life’s work to study and spread awareness of the history of African Americans. In 1915 he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now called the Association for the Study of African American Life and History) to support research into African American history and educate the wider public about it through both scholarly and popular publications.

Image: Google

Image: Google

To the same end, Woodson and his Association celebrated Negro History Week in 1926 during the second week of February, dates so chosen because they included the birthdays of both Frederick Douglass (exact date unknown, but Douglass celebrated it on February 14) and Abraham Lincoln (February 12). The Week was taken up by cities and states across the country in the next few years. In 1970, students at Kent State University inaugurated Black History Month; six years later, during the bicentennial, President Ford officially recognized the Month.

Woodson’s focus on Black History and education was based in his belief that knowledge of this neglected but proud history could help end racial prejudice and that white education had severely failed African Americans. In his seminal 1933 book The Mis-Education of the Negro, he wrote that through modern education “the Negro’s mind has been brought under the control of his oppressor… When you control a man’s thinking you do not have to worry about his actions.” He continues, “The same educational process which inspires and stimulates the oppressor with the thought that he is everything and has accomplished everything worth while, depresses and crushes at the same time the spark of genius in the Negro by making him feel that his race does not amount to much and never will measure up to the standards of other peoples.”

Thus, Woodson sought to educate African Americans – and whites – about their own past rather than stick with an educational system which ignored, caricatured, or downplayed the achievements of black people in America. He published books such as The History of the Negro Church, A Century of Negro Migration, African myths and folk tales, Negro makers of history, and many more, including an unfinished Encyclopedia Africana. His widespread scholarship makes up some of the founding work of what is now known as African American History or Africana Studies. His integral scholarly legacy is also obvious in the numerous libraries and schools named after him across America; Chicagoans might recognize his name from the Chicago Public Library’s South District Regional Library in Washington Heights, which includes an impressive collection on Black History, the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature. In his honor, why not go there and learn something new?