Langston Terrace Dwellings

Langston Terrace Dwellings

In the mid-1930s, there were 20,000 architects in the United States. Only 20 of those architects were people of color. Among those 20 was a young black architect named Hilyard Robinson.

Watch the Segment

Robinson had returned from an 18-month tour of European cities with his eyes opened to Modernist styles and ideals. He believed in the power of architecture to change lives, and his studies had shown him the potential of government-sponsored housing to address the needs of the poor.

When he was chosen by the New Deal’s Public Works Administration (PWA) to design the first federally-funded public housing project in Washington, DC (and only the second in the entire nation), Robinson brought a clean, modern perspective shaped by the International Style, which he had seen in Germany, Austria, and the Netherlands.

Web Exclusive Video

Hoping to uplift the lives of residents, Robinson created a design for Langston Terrace Dwellings in direct opposition to the tenements of the prior decades. He created a low-rise, sleek development of 274 apartments and row houses in a setting that responded to its landscape and showed that publically funded housing could be aesthetically pleasing.

Working with prominent black landscape architect David Augustus Williams, Robinson included a central courtyard commons, offering a gathering place for residents; playgrounds for the children; and places for public art by Works Progress Administration (WPA) artists.

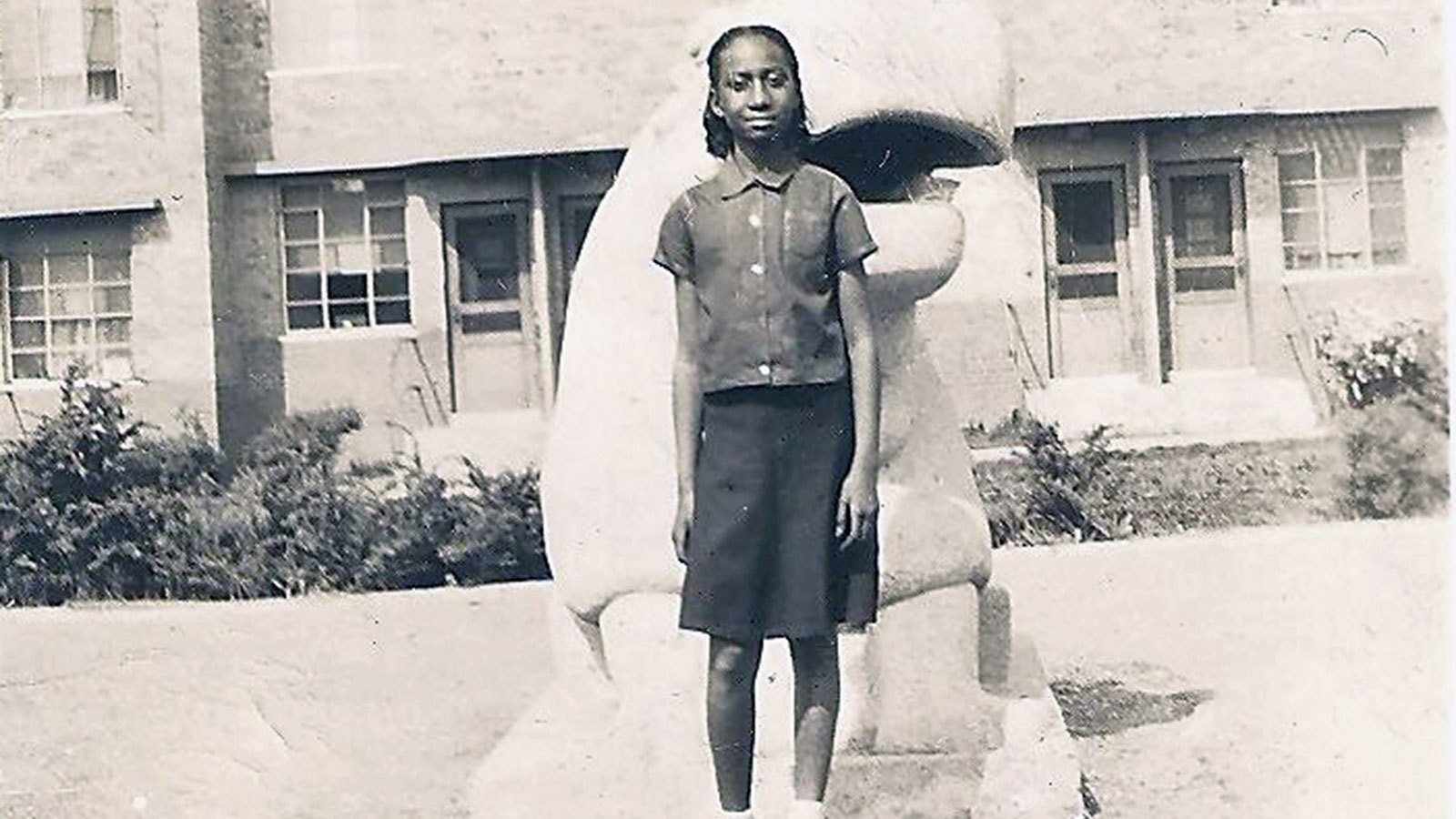

A large terra cotta frieze in the central courtyard, titled The Progress of the Negro Race, portrays black labor and migration from rural fields to urban industrialization. Large and fanciful frog, walrus, hippo, and horse sculptures enhance the playground. These sculptures were fondly remembered by Eloise Little Greenfield, who moved to Langston Terrace on her ninth birthday and went on to become an author of children's books: "They were friends to climb on or to lean against, or to gather around in the evening. You could sit on the frog's head and look out over the city at the tall trees and rooftops."

Langston Terrace Dwellings welcomed its first residents in 1938. It was named for John Mercer Langston, the abolitionist and U.S. congressman who founded Howard Law School. Its success helped to spur passage of the national Housing Act. And while it did not solve all of the problems of the poor, it provided 274 families (selected from a pool of 2200 hopeful applicants) with decent, affordable housing. As Greenfield described it:

For us, Langston Terrace wasn't an in-between place. It was a growing-up place, a good growing-up place with neighbors who cared, family, friends, and a lot of fun. Life was good. Not perfect, but good. We knew about problems, heard about them, saw them, lived through some hard ones ourselves; but our community wrapped itself around us and put itself between us and the hard knocks, to cushion the blows.

Learn More

- Read a detailed history of Langston Terrace Dwellings.

- Review the National Register of Historic Places listing for Langston Terrace Dwellings.

- Watch interviews with long-time and former residents.

- Read about a plan under consideration to redevelop the former Langston Terrace power plant as a renewable energy operation.