Gateway Arch

Gateway Arch

Join Geoffrey for a ride to the top of Eero Saarinen’s famous arch, a memorial to Thomas Jefferson and a gateway to the West.

The Gateway Arch is a testament to Americans’ vision, ambition and audacity – a feat of engineering, a marvel of political maneuvering, and a stunning work of modern architecture.

The official story is that the Midwest’s most recognizable monument was built to pay homage to St. Louis’s role as the waystation for early westward explorers, including Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

But historians such as Tracy Campbell, author of The Gateway Arch: A Biography, say that the project’s primary impetus was racism and a desire to raze what had become a largely low-income, African American community in the heart of St. Louis.

In the 1930s, the area that the arch now stands on was home to some of St. Louis’s oldest buildings and, before that, its earliest settlers. It was the center of the western fur trade and later a central shipping hub where river boats traveling along the Mississippi River docked and transferred their goods to covered wagons headed westward.

But after the introduction of the railroad and then the automobile, the center of commerce in St. Louis shifted. Many of the old riverfront buildings fell into disrepair. Then the Great Migration and a 1917 race war across the river in East St. Louis brought an influx of poor African American residents to the area.

Local lawyer and St. Louis booster Luther Ely Smith had the idea to demolish the area while riding a train across the river, entering St. Louis.

“This was the first thing that greeted you in the 1930s,…some old, somewhat rundown buildings that looked old-fashioned, didn’t look like the image that they wanted to portray of St. Louis,” explains National Park Historian Bob Moore. “So Luther Ely Smith saw these buildings and said, ‘We can do better. St. Louis can look better.’”

In late 1933, Smith proposed razing the entire neighborhood and creating a park that would both elevate the city’s profile and attract federal construction dollars. He pitched the idea to St. Louis Mayor Bernard Dickmann, and soon local political and business leaders got on board. City engineer W. C. Bernard specifically touted the plan as “an enforced slum-clearance program.” They hoped the project would create jobs – and boost real estate values.

They soon arrived at a concept that could draw national interest and financial support: a monument that would pay tribute to St. Louis’s role as the gateway to western expansion and honor Thomas Jefferson, responsible for signing the Louisiana Purchase. (Conveniently, he was also a favorite of then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt.)

The Roosevelt administration embraced the proposal. In 1935, Roosevelt signed an executive order ensuring a three-to-one federal match for the memorial and enough funds through the Public Works Administration to begin the building condemnation and demolition process.

But it took another few years of negotiations, lawsuits, and a rigged referendum in support of land-clearance bonds before the first building finally came down in 1939. In the end, 39 blocks of buildings – 91 acres of early St. Louis architectural artifacts, as well as existing, predominantly black businesses and homes – were leveled to make way for the monument.

World War II eventually halted federal funds, with many legislators unconvinced that a memorial in St. Louis, Missouri, ought to be a national priority.

And so it wasn’t until 1947 that the planning committee finally launched a national competition for the monument’s design. The prize attracted interest from big-name architects, including Finnish-born Eliel Saarinen, who had designed art nouveau landmarks in his home country before moving to the U.S. and peppering several American cities with his art deco and Gothic designs.

In September 1947, Saarinen received a congratulatory telegram.

In an interview decades later, Lilian Swann Saarinen, Eliel Saarinen’s daughter-in-law, said that upon hearing her father-in-law’s news, she traveled to his home to celebrate with her husband Eero, Eliel’s son and prodigy, who had also submitted his own design.

“And then when we got back, just as we walked in the door, the telephone rang, and it was [competition adviser] George Howe on the phone, and he said he felt simply terrible, that he'd made an awful mistake. It was Eero who had won it.”

But her father-in-law took the news in stride.

“Eero called that up to his father, and his father said, ‘Well, congratulations, come on over and have another bottle of champagne.’ Which we did, of course,” she said. “And then Eliel was happy in two ways. He'd come that close, and his son had come first.”

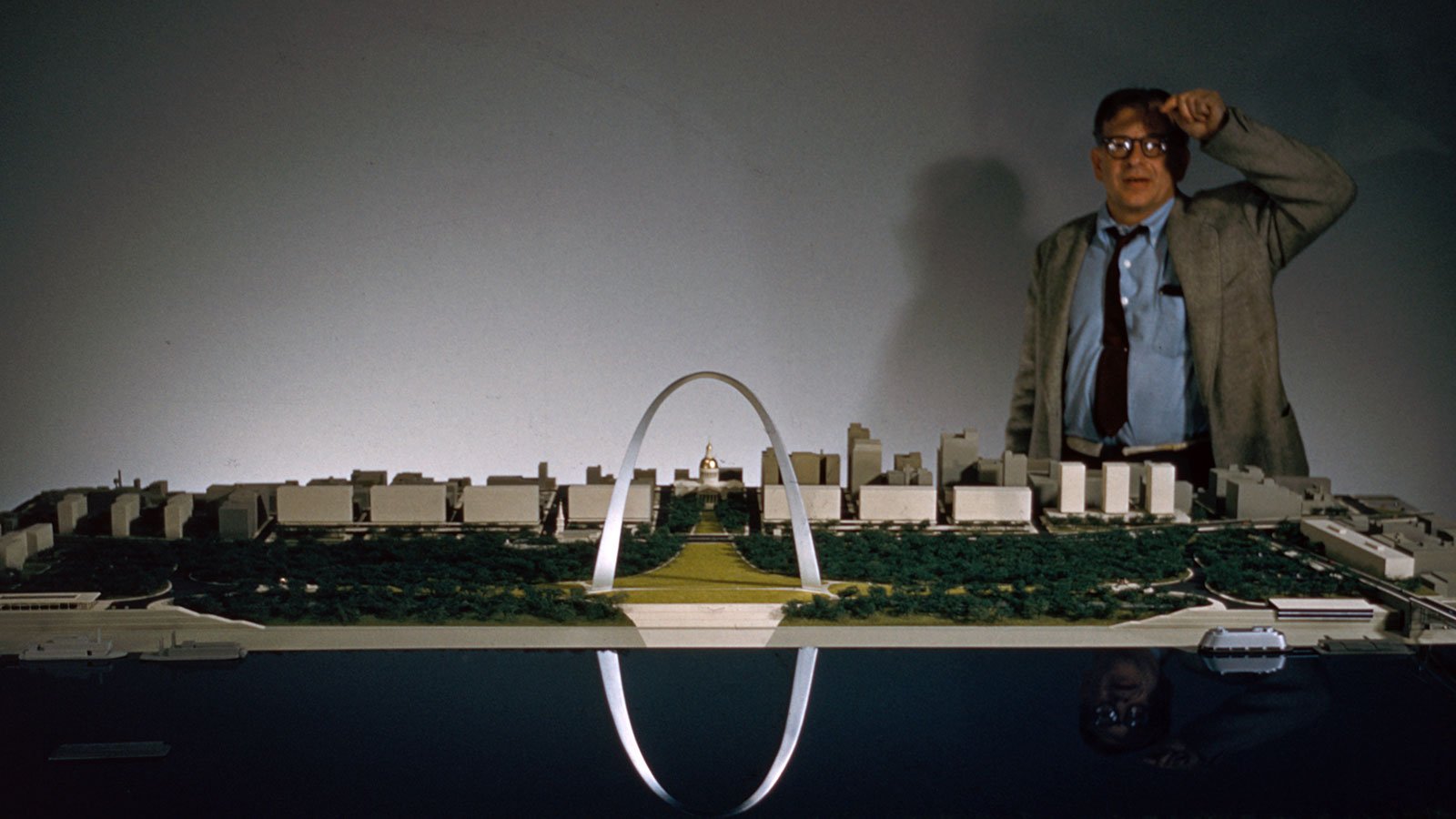

Eero Saarinen’s design was a drastic departure from past memorials.

“It’s the first time someone, in a very profound way, steps outside the tradition of neoclassical expression of memorializing, and it shocks people,” said Reed Kroloff, architecture critic and historian.

“They were asking people to represent the bigness of the vision of America, something that’s jumping the largest river of that continent and sweeping unstopped to the other coast,” he said. “It’s a beautiful, simple…mathematical equation spelled out.”

Eero Saarinen had honored the past but with a new kind of monument for the modern age.

But funding for construction lagged. Then in 1961, fourteen years after he won the memorial design competition and just six months after crews began excavation work to build the arch’s foundation, Eero Saarinen died at age 51.

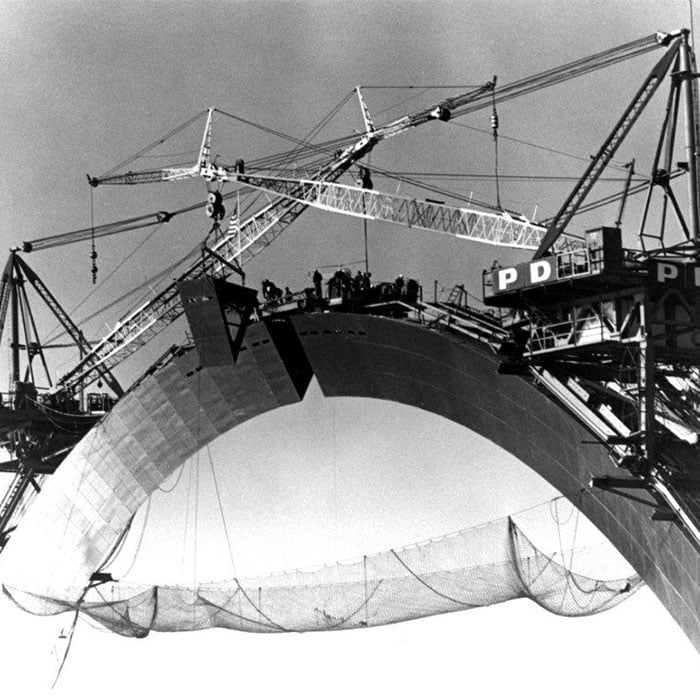

Construction of the arch itself began in 1963. Workers hoisted 142 stainless steel segments, one at a time, with incredible care and precision, slowly forming two elongated towers that joined in the middle into a catenary curve.

It was precarious work and took place before the advent of federal worker safety laws. The insurance company underwriting the project predicted that thirteen workers would die before the project was completed. But in the end, not one life was lost.

The project also took place at a time when racial discrimination was rampant in unions. Demonstrations at the site, combined with a landmark federal lawsuit over hiring practices, helped open the arch project, as well as the trades more broadly, to a greater number of black workers.

On October 28, 1965, crowds from throughout the St. Louis area gathered to watch the last triangular piece of the arch put into its place. In the end, the arch had cost nearly $13 million to build, or more than $100 million in today’s dollars. At 630 feet, it remains the tallest monument in the U.S.

The success of the arch is debated to this day. According to the National Park Service, more than 135 million people have visited the arch since it opened in 1965. But the ripples of development and prosperity haven’t traveled through the rest of St. Louis. In 1940, St. Louis was America’s eighth-largest city. Today its population ranking has fallen to 60th, and its per capita income, at $21,000, is far below the national median.

Still, the arch continues to be a great source of local pride. In recent years, another $380 million in local sales taxes, private dollars, and federal grants have been invested in upgrading the surrounding parkland and building a new underground visitor center. The center highlights the history of westward expansion, of St. Louis’s glory days, and of the great feats involved in constructing the massive arch. One of its exhibits includes a model of what the St. Louis riverfront looked like decades before large-scale demolitions made way for the arch.

“What we had was a national treasure. You know, the buildings that were here and the cast iron facades and everything was a national treasure,” said National Park Historian Bob Moore. “But we replaced it with an international icon.”