Chicago's Neighborhood Parks

Chicago's Neighborhood Parks

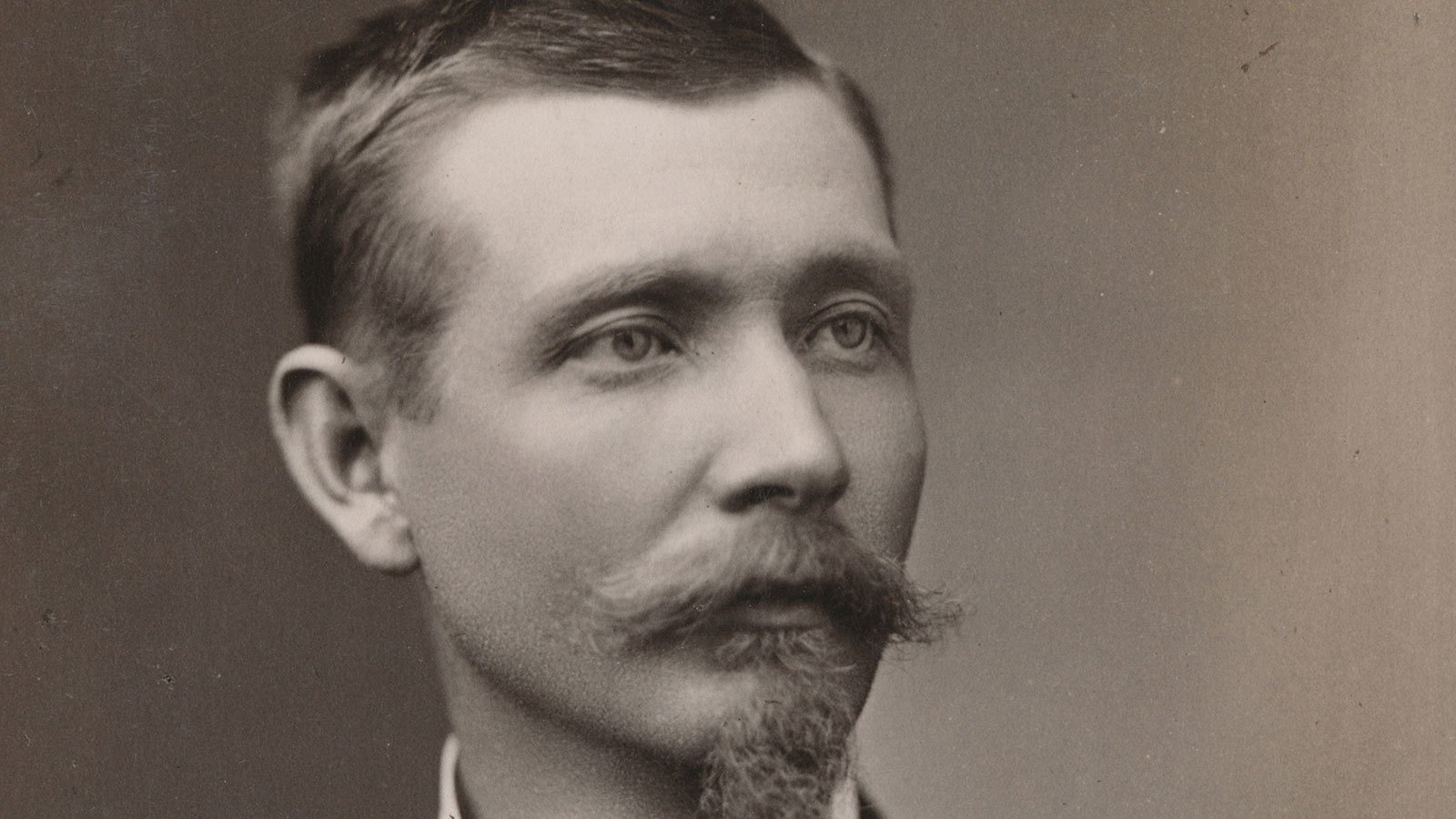

When J. Frank Foster took the job of superintendent of Chicago’s South Park System in 1891, the ideal of a city park was New York’s Central Park, which had created a nationwide trend of large landscapes.

Watch the Segment

Chicago already had several such parks near its lakefront, including Lincoln Park on the North Side, and Jackson Park and Washington Park on the South Side (connected by a green boulevard called the Midway Plaisance). These latter three were originally conceived as one "South Park" in 1871, covering a combined 1,055 acres. Their design, patterned on the Central Park model, was conceived by the same designers – Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux – whose pioneering work in Central Park made them the go-to designers for major park projects nationwide.

Jackson Park, Washington Park, and the Midway Plaisance were chosen to house the World's Colombian Exposition of 1893 and were at the time being urgently transformed by Frederick Law Olmsted and a cadre of the leading architects of the day, led by Daniel Burnham.

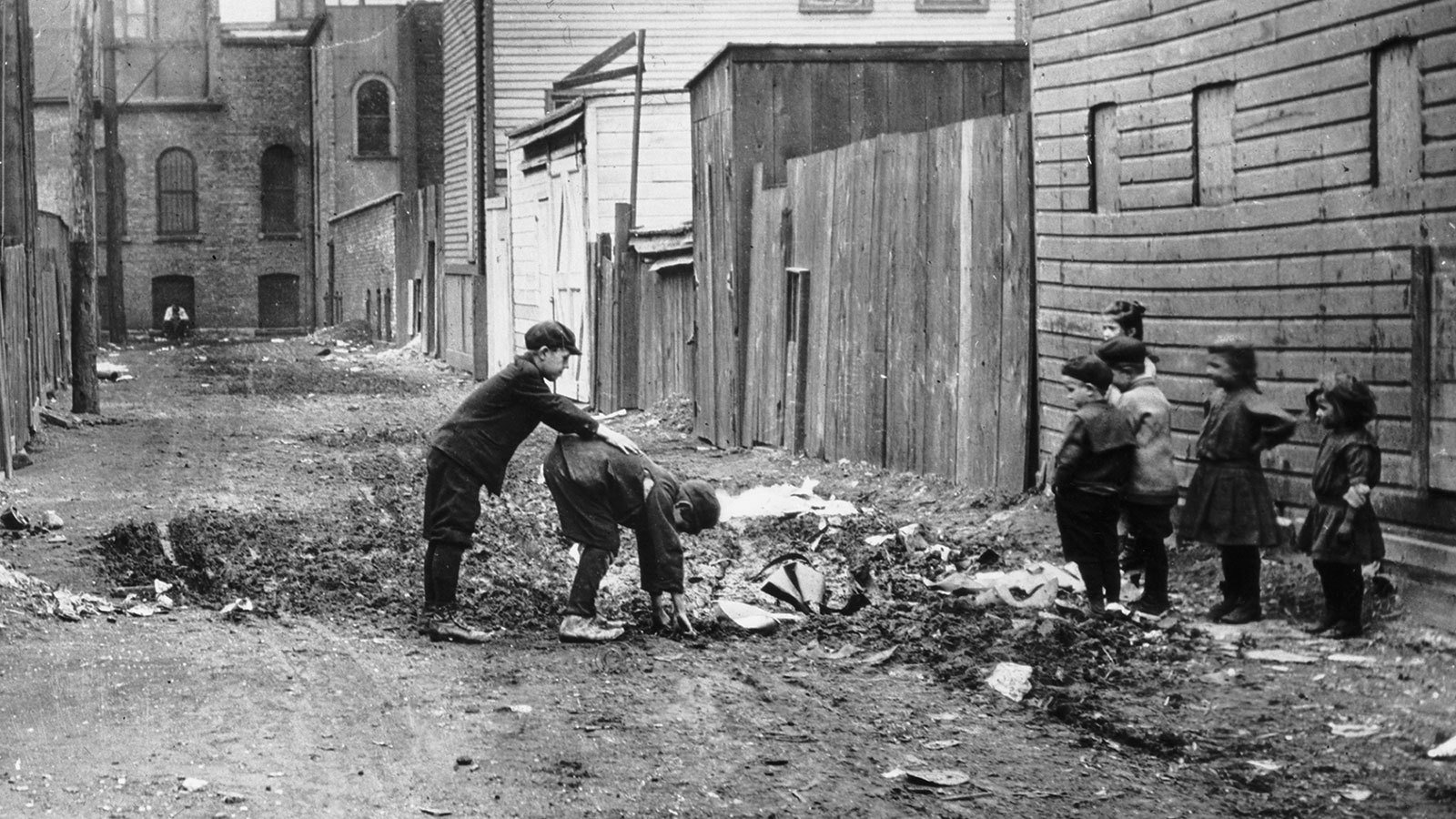

But while such parks were the pride and focus of Chicago's elite, Foster saw widespread social needs that were going unmet in the community. Vast tenement districts, geographically remote from the lakefront parks, housed poor immigrants who had no access to basic services. For these working poor, the idea of a lovely Sunday stroll by a landscaped lagoon was a luxury - perhaps even folly - when necessities such as health care, education, and basic hygiene were not addressed.

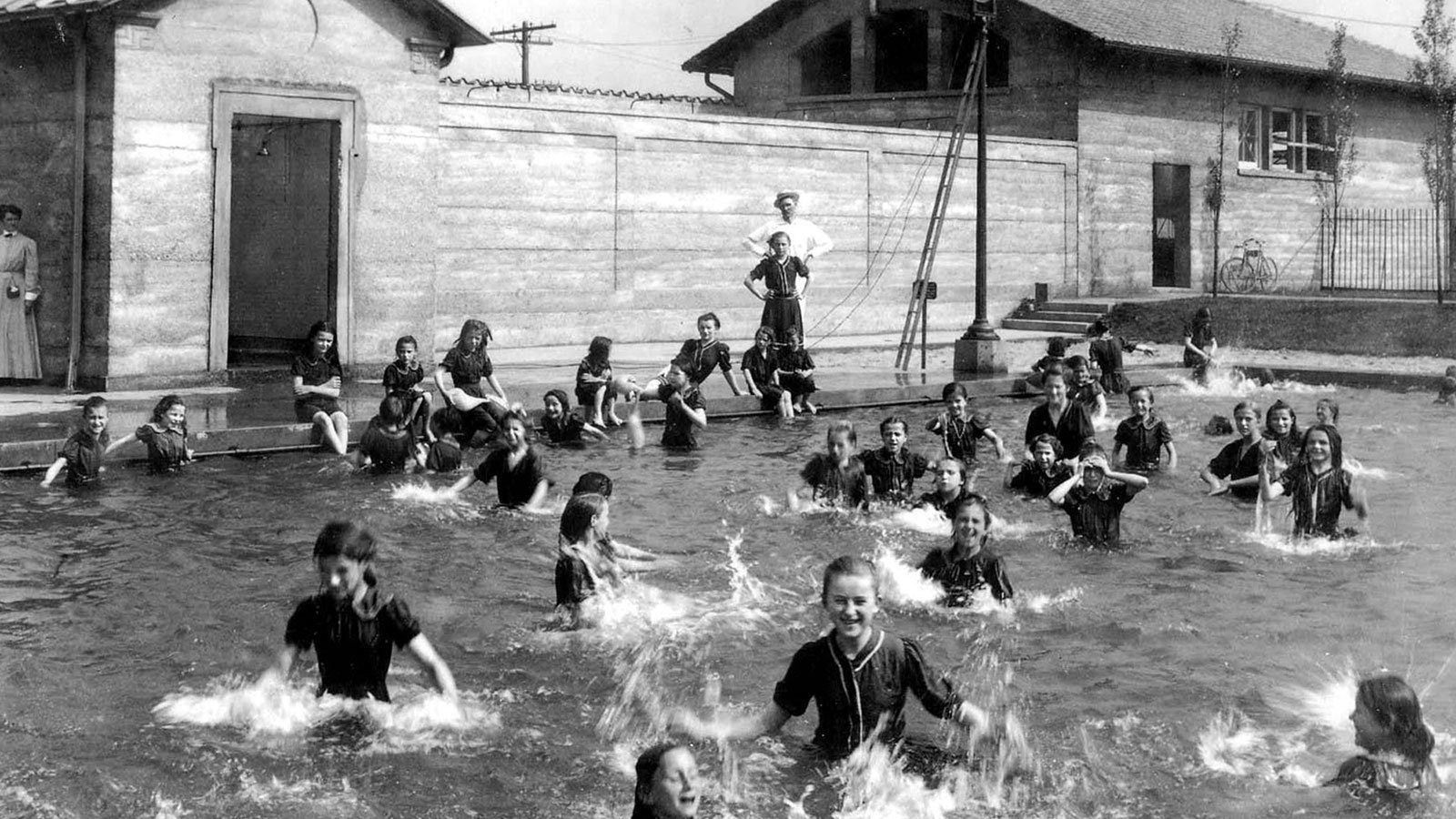

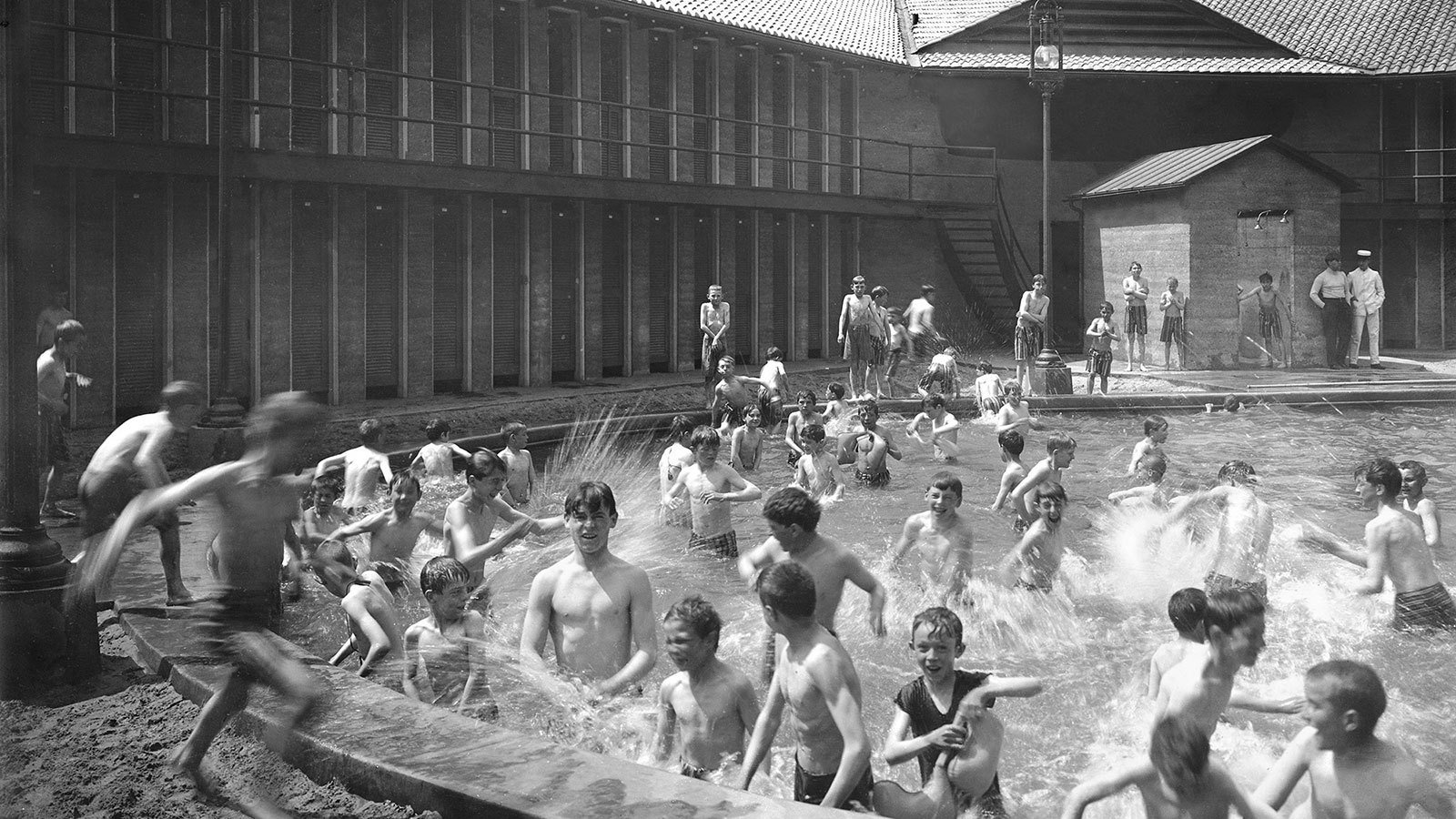

With this group of citizens in mind, Foster had a much more progressive idea for what a park could be. And he executed that vision in a system of smaller neighborhood parks that impacted the lives of Chicago’s working class for the better. These innovative parks were just the beginning in bringing amenities such as swimming pools, Chicago’s first branch libraries, gymnasiums, ball fields, and "fieldhouses" offering a wide variety of programs and services.

At these new-style parks, people could access nursing care, get a hot meal, take a shower, sign up for courses in English or hygiene, learn woodworking and crafts, participate in community theatre, and much more. The wide variety of programming expanded every year, as more needs were identified.

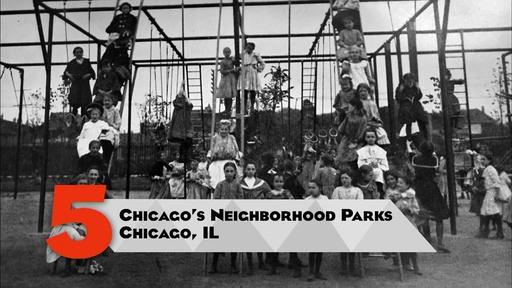

And for children, there was something new in the smaller parks: playgrounds. Foster’s parks expanded on a concept that had begun a few decades earlier, offering children supervised recreation and safer alternatives to the gritty streets and alleys of the tenement districts.

To design the new parks, Foster hired none other than Frederick Law Olmsted's sons, landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and John Charles Olmsted, who directed their family talents toward a more pragmatic and service-oriented approach to parks and recreation. Fieldhouses were designed by Daniel Burnham's firm.

Foster's concern for the people of Chicago's poor and immigrant neighborhoods helped transform the concept of what a park could provide. The parks were a great success, and many more were added in the decades that followed; today, Chicago has 300 fieldhouses. It was an idea whose impact reached far beyond Chicago.

Learn More

- View a map of Chicago's parks from 1913.

- Read more about J. Frank Foster.

- Explore some of Chicago's immigrant communities of 1895.

- View Olmsted's original 1871 design for South Park.