RED BRIDGE

Bridgeport

The Halsted Street Bridge over the South Branch of the Chicago River happens to be red, but that’s a coincidence. It was called the Red Bridge because of the blood that was shed there during the great railway strike of 1877 and the violent riots that ensued.

Battle of the Viaduct

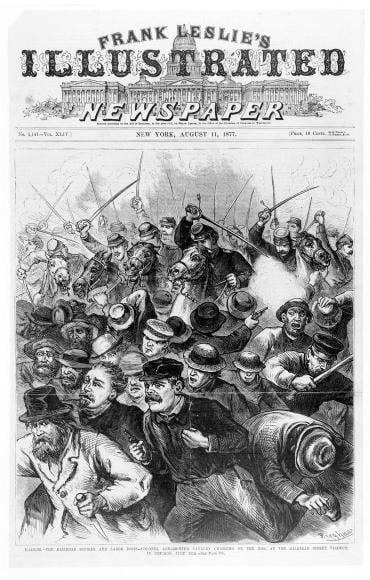

The Second Regiment of the U.S. Army sent its cavalry to suppress the mob. At least 18 people were killed, including one policeman. Scores were injured. The battle made the national press and was known as the Battle of the Viaduct. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

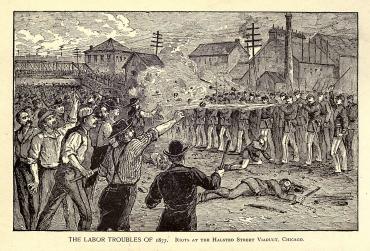

The labor demonstrators brought rocks and stones; the Army and police brought clubs and guns. Photo Credit: Public Domain

A few blocks north of the Bridgeport neighborhood, Halsted Street crosses the South Branch of the Chicago River. Some people used to call this the Red Bridge, not for the color of the bridge, but for the blood that was shed here when rioters and police met in an infamous series of battles.

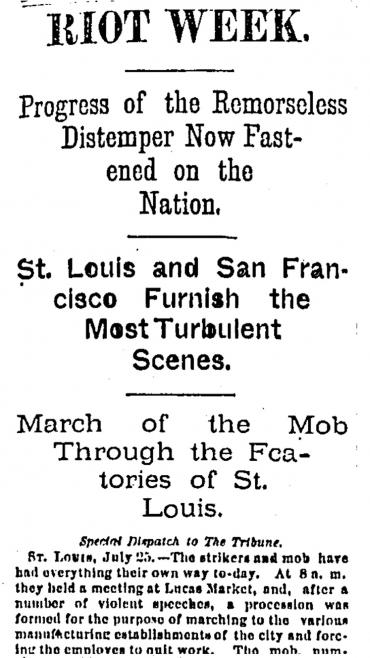

In July 1877, a national rail strike, inspired by cuts in rail workers’ wages, turned ugly in several cities. Mobs marching in St. Louis and San Francisco made headlines in the Chicago Tribune.

In Chicago on July 25, a crowd of workingmen marched along a route that moved through the rail yards and stockyards, picking up sympathetic workers and supporters along the way.

The group headed north up Halsted Street toward the viaduct at the Chicago River, where they were met not only by the police, but also by the U.S. Army’s Second Regiment. The violence that ensued became known as the Battle of the Viaduct.

It took the full force of the police, the infantry, and the cavalry to put down the angry mob. Uncounted numbers of rioters – and some innocent bystanders – were injured (uncounted, in part, because local women took the injured into their homes and hid them).

At least eighteen rioters were killed, as well as one Chicago policeman.

The Tribune’s bias against the workers, which would later play a role in Haymarket Affair, is evident as the newspaper labeled the marchers, many of them Irish, as “people of poor classes,” “savages,” “brutes,” and “greasy rioters” – and even describes the women as “amazons” and children as “waifs.”

As for justice, the Tribune reporter says of the people clubbed by police: “Some who didn’t move fast enough, or who persisted in going south, were knocked down with clubs and were badly bruised. These men who were clubbed [by police] were doing nothing, but they deserved what they got, since their place was at home, and not attempting to swell a crowd.”

Palmisano Park

On their way to the battle, the marchers likely passed the former Stearns Quarry, a few blocks south of the Halsted Street Bridge. The quarry was in operation from the late 1830s until 1970; after that, the site was used as a landfill for clean construction debris.

In 2009, after a $10 million remediation and renovation, the site re-opened as Palmisano Park – an innovative, 27-acre green space with a stocked fishing pond 40 feet below street level, plus hiking on a hill that owes its origins to the aforementioned construction debris – right in the middle of Bridgeport.

It is certainly one of the more unusual properties in the Chicago Park District portfolio. The park is named for the late Henry Palmisano, whose family owns sports and shop at the east end of Bridgeport.

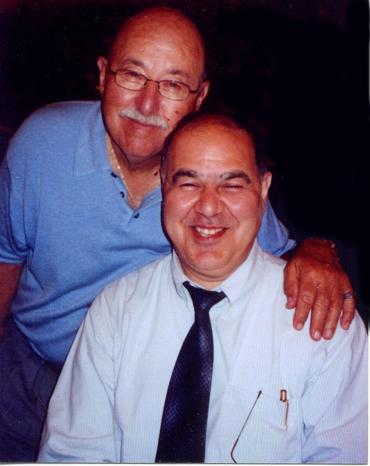

Palmisano Park was named for Henry C. Palmisano, owner of Henry’s Sports, Bait and Marine Shop, who died at age 54 in 2006. Palmisano was an advocate for local fishing. His work is carried on by his brothers, who continue to offer fishing programs for kids at Palmisano Park. He is shown here with his father, Henry J. Palmisano, who opened the Bridgeport shop in 1952.

The Chicago riots were part of a national strike that broke out after railroads tried to cut workers’ wages. In several cities, the labor demonstrations turned violent. These Chicago Tribune headlines appeared the day before the first riots in Chicago.

Just a few blocks south of the bridge, this limestone quarry was in operation from 1830 through 1970. After the quarry closed, the site became a landfill, accepting such clean construction debris as lumber and ash. But its next incarnation would be the most unusual. Photo Credit: Chicago Park District

In 2009, the park was not so much restored as completely re-imagined – as a green space with a topography made possible by its former industrial uses. The quarry’s deep void became a below-grade, stocked fishing pond, and a pile of construction debris became a man-made hill – the first such hill in nearly 14,000 years, when retreating glaciers scraped them away.