From Riots to Renaissance: Bronzeville: The Black Metropolis

Bronzeville: The Black Metropolis

From the 1920s through the 1950s, Chicago's South Side was the center for African-American culture and business. Known as "Bronzeville," the neighborhood was surprisingly small, but at its peak more than 300,000 lived in the narrow, seven-mile strip.

Chicago's black population stretched along 22nd to 63rd streets between State Street and Cottage Grove. But the pulsing energy of Bronzeville was located at the crowded corners of 35th and State Street and 47th Street and South Parkway Boulevard (later renamed Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive). At those intersections, people came to see and be seen, shop, conduct business, dine and dance, and experience this bustling black metropolis. The crowds reflected the diverse mix of people living in the black belt: young and old, poor and prosperous, professionals and laborers.

Bronzeville was well known for its nightclubs and dance halls. The jazz, blues, and gospel music that developed with the migration of Southern musicians attracted scores of diverse listeners and admirers. In the 1920s, the Regal Theater opened its doors and hosted the country's most talented and glamorous black entertainers. The community was also home to many prominent African-American artists and intellectuals, including dancer Katherine Dunham, sociologist Horace Clayton, journalist and social activist Ida B. Wells, jazz man Louis Armstrong, author Richard Wright, and poet Gwendolyn Brooks.

Bronzeville's businesses and community institutions Provident Hospital, the Wabash YMCA, the George Cleveland Hall Library, Parkway Community House, the Michigan Boulevard Garden Apartments, Binga Bank, Overton Hygienic Company were more than alternatives to racially restricted establishments downtown. They were pillars of the community which helped to instill pride and contribute to the upward mobility of African Americans.

But Bronzeville fell into decline after the end of racially restricted housing. Upper and middle class families moved away, and over-population and poverty overwhelmed the neighborhood. Today, black heritage tours guide visitors to the nine architectural landmarks that remain from the historic community, while neighborhood groups and business interests continue to work toward rebuilding the "city within a city" that was once a national center of urban African-American commerce and art.

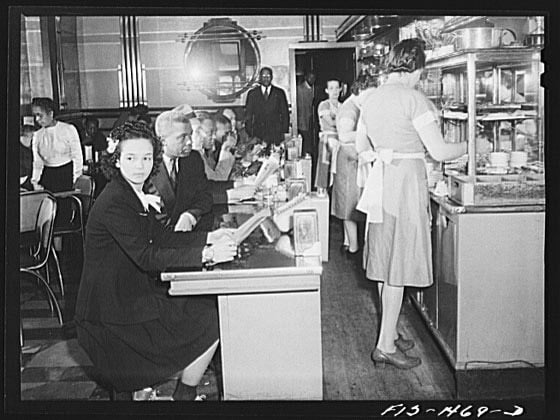

Celebrities at the next table

(Source: Library of Congress)

"At an exclusive 'Eat Shoppe' just off the boulevard, you may find a Negro Congressman or ex-Congressman dining at your elbow, or former heavyweight champion Jack Johnson, beret pushed back on his head, chuckling at the next table; in the private dining room there may be a party of civic leaders, black and white, planning reforms."

- Black Metropolis

Awed by Bronzeville

Susan Cayton Woodson remembers the thrill of arriving in Bronzeville for the first time after a cross-country road trip with Gene Coleman and renowned singer and actor Paul Robeson.

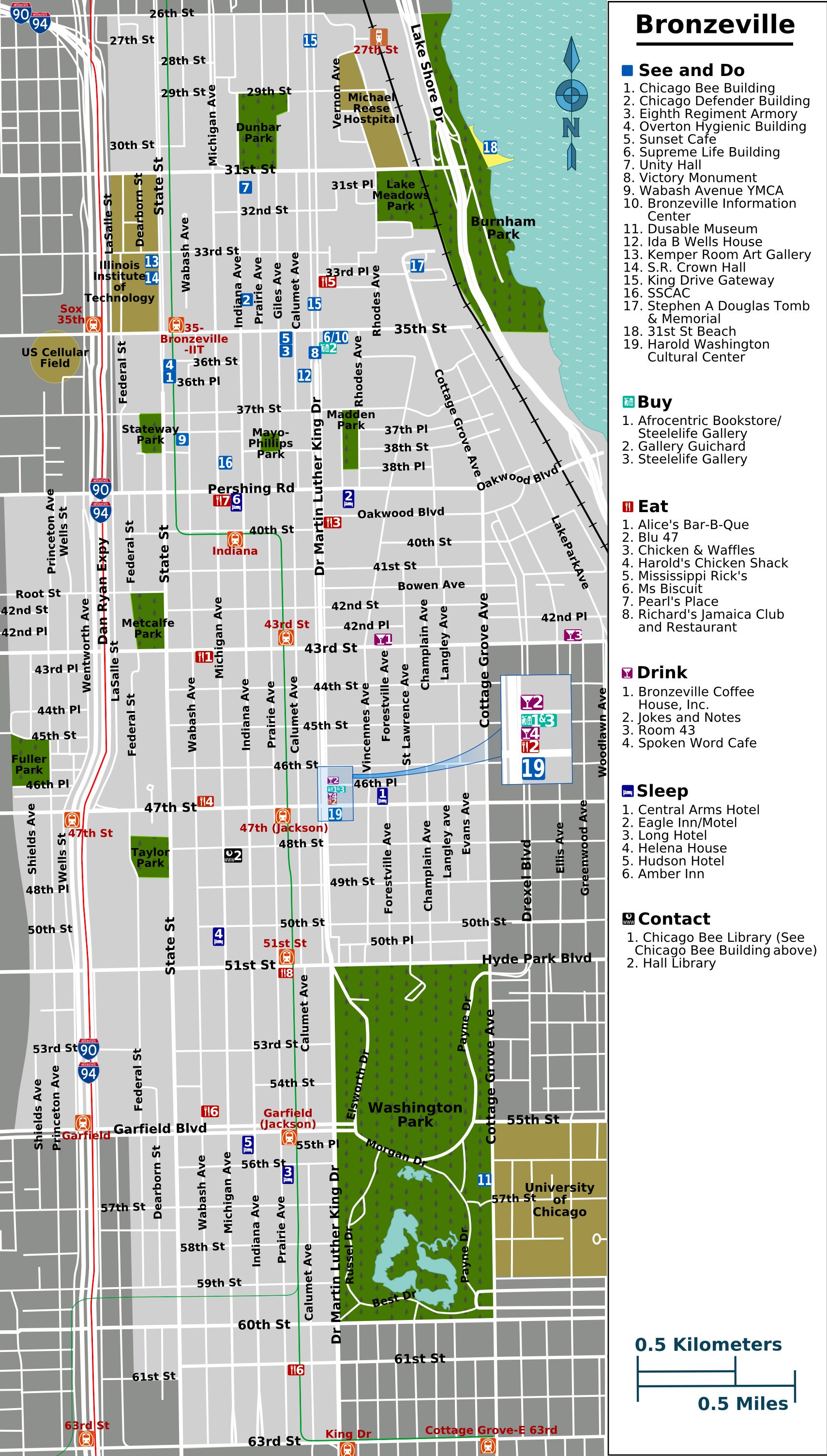

Map of historic Bronzeville buildings

Dave Young’s Group

Source: Library of Congress

Bronzeville had the best of black entertainment. Jazz, blues, dancing, theater and more could all be found at the nightclubs and theaters that dotted the Southside.

Planning meeting

Source: Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature

Many residents in Bronzeville were socially and politically active. In 1940, this group was meeting to plan a proposed march on Washington led by A. Philip Randolph.

Bud Billiken 8th Regiment

Source: Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection

Public events, like the Bud Billiken Parade shown here, picnics, concerts, lectures, exhibitions, and athletic events were plentiful.