Go Beyond Chicago from the Air

How did Chicago become one of America’s boldest and most dynamic cities with its location way out in the middle of the country? The keys to that story are in the waterways — both natural and human-made — and in the land that drew people to settle here. Traveling by air beyond Chicago’s borders, out into Illinois, and back through time, the water and land that paint the landscape tell the stories of people who fought, built, reshaped, and restored this region.

Waterways

The Mississippi River carves its way through the United States, starting in Lake Itasca, Minnesota and emptying into the Gulf of Mexico. For 581 miles, it winds its way along Illinois’s western border.

In 1886, Mark Twain told the Chicago Tribune how “strange” it was that not much had been written about the upper Mississippi compared to what had been written about the river south of St. Louis. Twain — a riverboat captain named Samuel Clemens before he assumed his pen name — told the reporter, “Along the Upper Mississippi every hour brings something new. There are crowds of odd islands, bluffs, prairies, hills, woods, and villages — everything one could desire to amuse the children.” In northwestern Illinois, Mississippi Palisades State Park captures the spirit of Twain’s description with impressive views and limestone formations. Twain grew up in Hannibal, Missouri, just down the river from Quincy, Illinois. Hannibal served as the inspiration for Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn’s hometown.

The Mississippi River shaped commerce in the midwest and beyond – and helped Chicago become an important trading hub.

The Mississippi River was a key route for European explorers, traders, and colonizers. By the 1800s, through a series of treaties, the United States government had pushed many Native American tribes to the land west of the Mississippi River, and the river became a commercial route, teeming with steamboats. Eventually, the railroad industry surpassed the steamboat, but cargo is still shipped along the Mississippi River on barges. Today, the Great River Road allows people to follow the river by car, with 3,000 miles of road following the Mississippi across 10 states.

Near where the Mississippi and Missouri rivers meet is a small town jam-packed with history. On October 15, 1858, Alton, Illinois was the stage for the seventh and final debate between Abraham Lincoln and Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Lincoln was challenging Douglas for his senate seat, while arguing for the abolition of slavery in the United States. The Elijah Lovejoy Monument, a 10-story column located in Alton, also acknowledges the town’s ties to abolition. Lovejoy was a Presbyterian minister and editor of an abolitionist newspaper. He continued to publish the newspaper despite death threats, but he was ultimately killed by a pro-slavery mob when they attacked his printing press. Because of Alton’s location on the river, the homes of many Alton residents were stops on the Underground Railroad as people who were enslaved fled north.

Down the river from Alton, the Lewis and Clark Confluence Tower marks the spot where the Missouri River and the Mississippi River — the country’s two longest rivers — converge. The 150-foot tower was built to acknowledge the location where Meriwether Lewis and William Clark began their two-year expedition. Starting in 1804, the men and their crew traveled 8,000 miles up the Missouri River to explore the American West and to find a route to the Pacific Ocean.

As Chicago grew, the city’s industry needed access to the commercial waterways of the Mississippi River. The Illinois and Michigan Canal served that purpose for several years upon its completion in 1848. Mostly Irish immigrants constructed the canal, which connected the Chicago River in Bridgeport with the Illinois River in LaSalle, Illinois. But as railroads took over, traffic in the canal dwindled and effectively ceased by the early 1900s. Today, one of two mules — Moe or Larry — pulls a replica of an 1840s canal boat called The Volunteer.

Nearly 50 years after the Illinois and Michigan Canal opened, another, bigger canal called the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal was constructed alongside it to carry Chicago’s wastewater away from Lake Michigan and down to the Mississippi River. In a massive feat of engineering, the canal reversed the flow of the Chicago River to carry diseases away from Lake Michigan — the source of Chicago’s drinking water. The Lockport Lock and Dam controls the flow of that water. When it opened in 1907, the dam had hydroelectric generators that supplied some electricity to Chicago’s parks. It still generates a small amount of power and is the only hydroelectric dam in the Chicago area.

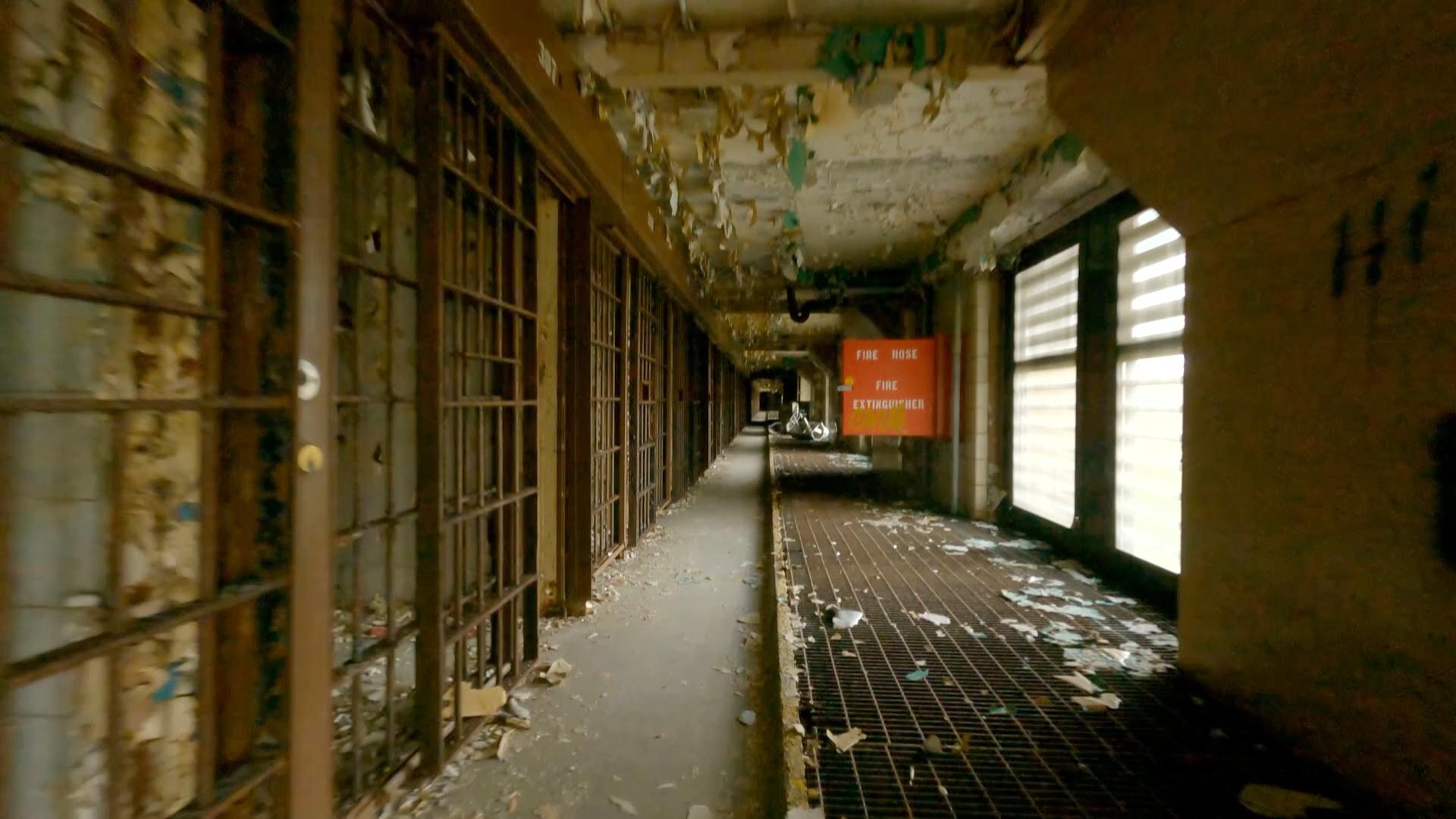

See the abandoned halls of Old Joliet Prison from the perspective of a first-person view drone.

Further downstream in Joliet, water traffic keeps the Des Plaines River so busy that workers staff the moveable bridges 24 hours a day. Not far from the river’s edge, Old Joliet Prison looms. The prison was built out of limestone by the prisoners themselves and opened in 1858. It was notorious for its foul conditions but didn’t close until 2002. The prison, which has been used during the filming of several movies and television shows, is probably recognizable to anyone who’s seen The Blues Brothers, as “Joliet Jake” was an inmate there.

(1) The Lockport Lock and Dam; (2) Old Joliet Prison Photos: Colin Hinkle / WTTW

While some of Illinois’s rivers are busy with boat traffic, others are busy with foot traffic. Along the DuPage River, the Naperville Riverwalk is a 1.75-mile scenic trail that follows the banks of the river. Three small lakes that were once quarries sit along the path. Families go to enjoy swimming, paddleboats, kayaking, or sunbathing at Centennial Beach.

Centennial Beach in Naperville Photo: Colin Hinkle / WTTW

Closer to the Wisconsin border, things get a little more adventurous. Chain o’ Lakes near Fox Lake is home to drag boat races where competitors race 800 feet across the lake every week in the summer. The lakes were also once the home of rare American lotus flowers, which were picked every August until they stopped growing. However, in recent years, the lotuses have started to reappear. The adventure on the water doesn’t stop when icy winter comes to the region. Down the Fox River from Chain o’ Lakes is the Norge Ski Club. Norwegian men started the club in 1905 so they could practice their beloved sport: ski jumping. Today, Olympic athletes train at the facility. Atop the 160-foot hill, jumpers soar off the 10-, 20-, and 70-meter towers.

The Land

Beyond the skyscrapers, mass transit, and general bustle of Chicago, amber waves of grain blanket the land. According to the Illinois Department of Agriculture, 75 percent of the Prairie State’s land area is farmland. On the state’s 72,000 farms, farmers tend to their corn, wheat, soybeans, fruits, vegetables, livestock, and even ostriches and Christmas trees.

A natural resource found below the soil in Galena, Illinois is lead. The word galena actually refers to the mineral form of lead sulphide. Though it may not quite glitter like gold, lead was originally mined by the Sauk and Meskwaki peoples and was later an important part of the mineral rush that brought those in search of fortune to Illinois in the early 1800s. Today, Galena appears to be frozen in time. The population of Galena dropped at the end of the nineteenth century with the decline of the lead industry, but the town was restored in the 1970s and now many of the buildings are part of a National Register Historic District.

In the 1830s, other settlers came to Illinois after hearing about the promising farmlands from soldiers fighting in the Black Hawk War. That land was farmed by Native American peoples until the Treaty of 1804 forced them to move west of the Mississippi River. But a Sauk warrior named Black Hawk thought the treaty was invalid because a small group of men without tribal authority had ceded the land. In April 1832, Black Hawk returned with 1,500 of his people to farm the land. A conflict quickly emerged with militias.

Apple River Fort in Elizabeth is a replica of the fort that Black Hawk and 200 warriors attacked during the war. Further east near Pearl City, Blackhawk Battlefield Park marks the location of the last battle fought in Illinois during the war and includes a cemetery for some of the militiamen who died in battle, though no such site exists for Native American people who died in the war. The United States Army eventually intervened, pushing Black Hawk and his followers back across the Mississippi River and killing many of them. More than 1,000 of Black Hawk’s followers died in the four-month-long war.

(1) Apple River Fort in Elizabeth, Illinois; (2) The Black Hawk Statue in Oregon, Illinois Photos: Colin Hinkle / WTTW

In Oregon, Illinois, a monument known as the Black Hawk Statue was originally designed as a tribute to Native American tribes in Illinois, but has long been associated specifically with Black Hawk, according to the town’s website. Sculptor Lorado Taft created the 100-ton figure, which stands 50-feet-tall atop a bluff. The statue was dedicated in 1911, and a years-long restoration project was completed in 2019.

The forced removal of Native Americans from the region ultimately paved the way for Chicago’s growth. But long before Chicago was incorporated, a massive Native American city called Cahokia (which was larger than London at the time) was home to as many as 20,000 Mississippian people. Today, anyone can visit the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site near St. Louis to see the earthen mounds that once wound their way around this city. Read more about the history of Cahokia at the link below.

Massive earthen mounds provide clues for a Native American city that was once the largest pre-Columbian city north of Mexico.

Starved Rock State Park near Utica gets its name from a Native American legend. In the eighteenth century, an Ottawa chief named Pontiac was stabbed by an Illiniwek warrior. During the battle that ensued, the Illiniwek sought refuge on a butte. The tale says that because they were surrounded by Ottawa and Potawatomi warriors and without food, the Illiniwek died of starvation. Starved Rock became a state park in 1911 and offers a change in the state’s mostly flat landscape.

Another deviation from the flat prairie lands sits closer to Chicago in Lemont. Sagawau Canyon is the only natural canyon in Cook County, according to the Cook County Forest Preserves. The canyon is part of the forest preserve system that surrounds Chicago. Landscape architect Jens Jensen, architect Dwight Perkins, and city planner Daniel Burnham played key roles in fighting for a permanent forest preserve system in the early twentieth century in order to preserve some of the area’s natural beauty as the city expanded into the landscape. Today, more than 70,000 acres of forests, prairies, wetlands, lakes, and streams are protected by the Cook County Forest Preserves, including Bemis Woods outside Western Springs, Illinois, which features a zip-line attraction called Go Ape.

Fly through the scenic Sagawau Canyon near Lemont, Illinois with a first-person view drone.

One popular forest attraction isn’t actually natural at all; it’s man-made. The Morton Arboretum in Lisle is an outdoor museum of trees. Joy Morton, the founder of the Morton Salt Company, first built a country home on the land in 1909 and later transformed it into the arboretum, which opened in 1922. Morton was the son of J. Sterling Morton, a U.S. secretary of agriculture and the man who created Arbor Day. Today, the arboretum spans 1,700 acres complete with walking trails, a maze, and massive sculptures by South African artist Daniel Popper.

(1) The maze at the Morton Arboretum; (2) One of Daniel Popper’s sculptures at the Morton Arboretum Photos: Colin Hinkle / WTTW

Before the land was developed, 22 million acres of prairie covered Illinois, according to the Illinois Natural History Survey. Today, only 2,000 acres remain. Near Wilmington, the United States Forest Service operates the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie, which was once the location of the Joliet Army Ammunitions Plant, the world’s largest explosives and munitions factory at the time. After the plant closed following the Vietnam War, the prairie returned as native plants took root once more. It became the country’s first national tallgrass prairie in 1996. A herd of bison roam the prairie, which you can sometimes see on the Bison Cam. On another part of the former arsenal site is Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery, where members of the armed forces who meet a minimum active duty requirement may be buried with full honors.

The winds that ripple through Illinois’s prairie are being put to use at wind farms around the state, including Streator Cayuga Wind Farm in Odell. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, Illinois ranks fifth in the country for wind generation, but wind still accounts for only 11 percent of the state’s electricity.

The wind that powers some of the state has also formed the massive sand dunes on Indiana’s lakefront. Though it sits between a sprawling steel plant in Gary and a large coal and natural gas power plant in Michigan City, Indiana Dunes National Park stands in contrast to its surroundings with a rich, biodiverse ecosystem. Spanning 15,000 acres of dunes, savannas, swamps, marshes, and prairielands, it was first preserved as a national lakeshore in 1966 and became a national park in 2019. Explore even more of the Indiana Dunes on Geoffrey Baer’s Chicago on Vacation.

The Landscape Reshaped

The millions of people who have called Chicagoland home have reshaped the region’s water and soil over time. Many of the people that influenced Chicago and beyond were laid to rest in the city’s cemeteries. At Oak Woods Cemetery on the South Side, many prominent African Americans are buried. Journalist and civil rights pioneer Ida B. Wells and her husband, Ferdinand Barnett, are buried at Oak Woods. The cemetery is also the final resting place of track-and-field Olympian Jesse Owens, as well as the father of gospel music, Thomas A. Dorsey, publishing power couple Eunice and John H. Johnson of Ebony and Jet magazines, and former Chicago mayor Harold Washington.

First established on the North Side in 1860, Graceland Cemetery was once beyond the city’s borders. Landscape architect H. W. S. Cleveland designed the cemetery to feel like a park just outside the crowded, bustling city. Many architects are buried at Graceland, including Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Louis Sullivan, John Root, and Marion Mahony Griffin. Urban planner Daniel Burnham is buried on his own island. Other famous Chicagoans, such as Marshall Field, Cyrus McCormick, Bertha and Potter Palmer, Ernie Banks, and George Pullman, are all buried at Graceland.

In Union, Illinois, one museum celebrates precisely that which helped Chicago flourish: the railroad. By the mid-nineteenth century, Chicago had become the railroad capital of America as the city grew rapidly. The Illinois Railway Museum travels through that history with a collection of 450 pieces of railroad and other transit equipment. Its 100 acres also have train cars and five miles of track.

Chicago’s location in the middle of the country made it an ideal rail hub and allowed the city’s industry to flourish. The Chicago and Northwestern Railway Bridge close to the Merchandise Mart is near the spot where Chicago’s first railroad began. In 1848, the first train on the Galena and Chicago Union Railroad departed. In the 1860s, the line was consolidated with the Chicago and Northwestern line. The region’s railroad networks continued to grow. The grand scale of the convergence of several railroads is visible from the air at Blue Island Rail Yard Interchange south of the city. Today, 25 percent of the country’s freight trains still pass through Chicago, according to the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning.

(1) The Chicago and Northwestern Railway Bridge in downtown Chicago; (2) Railroad bridges at the Blue Island Rail Yard Photos: Colin Hinkle / WTTW

In Aurora, the former Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad Roundhouse is now a brewpub called Two Brothers Roundhouse. According to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad was the first railway to link Chicago to the Mississippi River. Built in 1856, the roundhouse was where steam engines were maintained and turned around for their return trips. Today, it is the oldest limestone roundhouse in the United States and is where Metra’s BNSF commuter line terminates.

Railroads also played a role in creating a popular North Shore concert venue. In 1904, the Chicago and Milwaukee Electric Railroad created Ravinia as an amusement park to get more people to ride the rails. Complete with a dance hall, casino, baseball diamond, and more, it was billed as “high-class,” alcohol-free amusement. Read more at the link below.

A railroad company was behind the creation of a popular North Shore entertainment and music venue. Uncover the early history of the park.

Across the Chicago region, unique buildings with interesting stories dot the landscape. Sitting at the edge of the Fox River in Plano, Illinois is the famous Edith Farnsworth House. Completed in 1951, the minimalist glass and steel house was designed as a peaceful country retreat by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe for Dr. Edith Farnsworth. The house cost more than double Farnsworth’s initial $30,000 budget, and she and Mies ended up suing one another. Farnsworth eventually sold the property to a British developer who preserved the house. With its proximity to the Fox River, the house has flooded several times and required various repairs and restoration. In 2004, it opened as a museum.

Get an up-close look at the Edith Farnsworth House with a first-person view drone.

While the glass walls of Farnsworth House were meant to open the home to the beauty of its natural surroundings, a quirky home in Oak Park looks as though it’s trying to achieve the opposite. With its thick, sloping walls and narrow windows, Kirsch House looks a little bit like a sandcastle — or a bunker. Built in 1982, the house was designed by Errol J. Kirsch and it stands out in the neighborhood of otherwise typical homes. Its goal was to be an early example of a sustainable and energy-efficient house.

The Fabyan Windmill is yet another oddity that soars 70 feet into the sky on the Fabyan Forest Preserve. Colonel George Fabyan purchased the property in 1914 and acquired more than 300 acres over the next two decades. He reportedly added the windmill because he liked bread made from freshly milled flour. Fabyan often invited scientists and other researchers to his property to live and work on projects that touched on his other eccentric interests. One of those researchers was a code-breaker who cracked an important Japanese code during World War II while living on the property. The windmill and the rest of the property are now part of the Kane County Forest Preserves.

Another stand-out property in Harvard, Illinois transports visitors back in time. RavenStone Castle may have been built in 2001, but it was designed to emulate a dramatic sixteenth century style. The Michel family built it themselves and now operate it as a bed and breakfast.

The Lipizzan horses at Tempel Farms in Old Mill Creek also have ties to the sixteenth century. According to the farm’s website, the Lipizzan breed “got its start in 1580 when Archduke Charles of the Austro-Hungarian Empire established a stud farm at Lipizza near the Adriatic Sea in modern-day Slovenia.” They were bred to pull carriages, fight in wars, and perform dressage; they came to Illinois in the 1950s after a couple visited a riding school in Vienna. Horses and their humans also get together at the Barrington Hills Polo Club, which is the only polo school in the area.

Those in search of a golf course in Illinois likely don’t need to look far, as there are hundreds in the state. Just west of Chicago, Medinah Country Club has hosted several major tournaments. The Shriners founded the private club, and the Middle Eastern-style clubhouse reflects the imagery that the Shriners often use. In Riverdale, Joe Louis “The Champ” Golf Course is named for the heavyweight champion and golf enthusiast. A champion of diversifying golf, Louis was the first person of color to compete in a PGA-sanctioned event, according to the PGA. In keeping with that tradition, Joe Louis Golf Course is also the home of the Chicago Women Golf Club, the second-oldest Black women’s golf club in the nation.

Back in Chicago, the lakefront is teeming with the energy of the people that flock to Lake Michigan. Whether it’s for a football game at Soldier Field, a concert at Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park, a casual volleyball game among friends at North Avenue Beach, or a group of sailboats competing in the Race to Mackinac Island, people continue to shape the land and waterways in Chicago and beyond.