Architects Marc & Nada Breitman | Geoffrey Baer Travel Journal

Geoffrey Baer Travel Journal

Filming the documentary Architects Marc & Nada Breitman: Talk of the Town early this year offered me some special delights in addition to filmmaking: travel to Paris, Northern France, and Amsterdam; using my Sony A6300 camera (although quite a few of the pics in this journal were shot with my iPhone 6); speaking French; and – food!

DAY ONE

We arrive at our hotel exhausted after an overnight flight to Paris from Chicago and the failure of our car service to show up at the airport.

Nonetheless, producers Dan Andries and Liz Reeves and I venture out to meet Marc and Nada Breitman, the husband-and-wife architect team we are here to profile. They are the winners of this year’s Chicago-based Driehaus Prize at the University of Notre Dame, being honored for their work in classical and traditional architecture. Charming people in a charming place! Their office is in the historic Paris district of Saint-Germain-des-Prés (Left Bank, 6th Arrondissment). Centuries-old buildings and streets barely wide enough for a single automobile. Just steps away is the Seine and Notre Dame Cathedral. Marc tells me their building dates from the medieval era, which can easily be seen in the exposed hand-hewn wood ceiling beams and rough stone walls.

Soon after arriving, we casually mention to Marc and Nada that we haven’t really eaten anything since our airplane breakfast. Marc immediately jumps up and puts on his coat to go and get us some pastries at one of his favorite local pâtisseries. I quickly don my coat to walk with him. I figure we’ll “bond” a little along the way. Very helpful to establish a relationship with someone I’ll be interviewing extensively. Less than 24 hours after leaving home, I send my wife a selfie looking somewhat French in my scarf, with an impossibly beautiful array of croissants, macarons, tartes, etc., etc., in the background.

I will continue to torture her with such selfies, including a photo of me holding up a pain au chocolat (a.k.a. chocolate croissant) on a bridge over the Seine with Notre Dame Cathedral in the background. I mean, how much more Paris can you get?

Throughout our time in Paris, we are offered coffee again and again. In the U.S., “coffee” means a large cup of something brown in varying degrees of strength adulterated with varying amounts of milk, cream, synthetic whitener, and real or artificial sweetener. But in France… it’s a tiny cup of something so flavorful that three sips is all you need – and all you get. There is always a sugar cube on the saucer. And even though I never sweeten my coffee in the U.S., I enjoy it immensely here. The idea of having this “to go” seems to be entirely foreign to the French. They sit and savor it.

It feels like they savor life itself here. Case in point: during our very first meeting with Marc and Nada, they tell us that the next day workers at one of their construction sites will be celebrating the completion of the building’s exterior walls with a traditional ritual that only the French could dream up. It’s a lavish meal of lamb cooked in a vat of boiling tar that is normally used for roofing material. It’s called “gigot bitume” (lamb cooked in tar). Dan and Liz immediately decide to chuck what we originally planned to shoot and bring our cameras to this celebration.

DAY TWO

Gigot Bitume. I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw it. The smoking vat looked – and smelled – just like the acrid roofing tar kettles you see everywhere. Except immersed in the boiling muck was… lunch. I completely forget that I haven’t spoken French in years, and start asking the chef a million questions. In French. Turns out he actually has a business going around to construction sites preparing this bizarre meal. He tells me the lamb is sealed up in aluminum foil and a kind of paper also used in building construction so that it never touches the tar, and that the meat has no taste of tar at all. And the lamb is only one part of the feast. There are impeccably prepared appetizers and side dishes, and of course the wine and champagne are free-flowing. It is DELICIOUS even though it’s served in a partially completed garage that’s unheated and the January air chills me to the bone. I only hope those construction workers didn’t go back to the job after that heavy meal and all that champagne. If they did I hope the next day they checked to make sure the walls were straight and the plumbing was hooked up correctly.

DAY THREE

Although we are in Paris to profile architects who eschew modernism (in fact disdain it!) in favor of classical and traditional design, we nonetheless visit a masterpiece of modernist architecture, UNESCO World Headquarters, built in 1958. A who’s-who of modern architects were involved in the design, including Marcel Breuer, Pier Luigi Nervi, Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Eero Saarinen, and later, Renzo Piano. But we’re not here for the architecture. We’re here to interview Assistant Director General for Culture Francesco Bandarin about Marc and Nada’s work restoring and rebuilding the coal mining towns of northern France in their signature traditional style. UNESCO has declared this now-defunct mining region a World Heritage Site. After the interview, while the crew is packing equipment, Francesco gives me an enthusiastic whirlwind tour of the building. In addition to the stunning architecture, he shows me artworks by Picasso, Tadao Ando, and others.

As I follow Francesco around I notice a few things that are unintentionally amusing, like a sign on an office door reading, “Director, Division of Creativity, Culture Sector.” The UN has managed to make creativity sound like a government bureaucracy.

And then I spot something that haters of modernism would point to gleefully. The sleek modern architecture leaves no room for something as untidy as a photocopy machine. So it sits in the hallway with its wiggly cord snaking up to the ceiling. Breuer, Nervi and the rest of them are rolling in their graves.

DAY FOUR

Today, we film our “hero” interviews with Marc and Nada in their home. Just steps from their office, it’s carved out of a former alleyway and an old printing shop. A lovely space they designed that blends ancient architecture and contemporary style.

How do we make a 30-minute documentary in two countries with just 10 days of filming (two of which are spent on airplanes)? Lots of preparation by producers Dan Andries and Liz Reeves before we depart and then marathon days of shooting! Dan directs what’s happening in front of the camera while Liz works the phone and computer, making sure things are on track for the hours and days ahead (and “going with the flow” as the inevitable complications arise. Liz calls it being “on the river”). I never cease to be amazed by our director of photography, Tim Boyd. He somehow manages to make stunningly beautiful images while also having to pack, schlep, and unpack hundreds of pounds of equipment. And after long days of filming, he still has to spend hours in his hotel room downloading the day’s footage to hard drives, putting batteries on charge, and prepping the gear for tomorrow.

Victor Borjat, Tim Boyd, Roland Venner, and Dan Andries.

Victor Borjat, Tim Boyd, Roland Venner, and Dan Andries.

Every day in Paris is so jam-packed with work that there is no time for sightseeing. This was the best view I got of the Eiffel Tower, from the fogged-up rear window of a taxi.

DAYS FIVE AND SIX

We have bid adieu to Paris. After a three-and-a-half-hour drive we are in the economically depressed former coal mining region of northern France. Quite a shock after having lived the Parisian life for five days. Since the mines closed in the early 2000s, this region has experienced as much as 50 percent unemployment.

I’m fascinated by the industrial-age worker housing. Endless rows of tiny residences all leading in one direction – to the mine. It reminds me of the Chicago neighborhood of Pullman, built in the 1880s as a company town for the famous railcar magnate’s empire.

The landscape in this region is dotted with what look like mountains but are actually towering heaps of coal mine waste called terrils. We are told that some are as large as the pyramids of Egypt.

A handful of Victorian-looking steel towers have been preserved. Called chevalements (headframes), they once lowered miners deep below ground and lifted coal to the surface.

The social safety net in France makes sure people have a roof over their heads. Marc and Nada have made a career out of upgrading typically austere social housing (what we call public or low-income housing) to something more humane and dignified. And they are beloved for it here. We found a mining town native to tell us about the Breitmans’ work. Jean-Pierre Kucheida turned out to be a real character, and one of my favorite interviews. He’s a well-known politician who represents this region. He answers my questions in a pompous manner as if making a campaign speech. At first it seems off-putting, but it quickly becomes endearing. And how could I not like a guy who keeps inserting “cher Geoffrey” (“dear Geoffrey”) into his answers? Kucheida’s father and both his grandfathers worked in the mines, where many didn’t live to see their 50th birthday. He said they never, ever wanted him to follow the same path.

I speak some French, but certainly not enough to understand the nuances in an interview. So we hired a translator whose name you might recognize if you are an NPR junkie like me: a Texas-born expat named Jake Cigainero (pronounced sig-AN-er-oh). He is periodically heard reporting from France on Morning Edition and All Things Considered.

Oddly, our lodging in this struggling region is in what looks at first like a palace, the Hôtel La Chartreuse du Val Saint Esprit. Turns out it’s a former monastery that the owners claim dates from the year 1320. The grand stairway, sumptuous lobby, and beautiful grounds seem anything but monastic. I keep expecting Mr. Carson from Downton Abbey to show up and offer to assist me.

For those of us who usually settle for what I call the “Styrofoam breakfast” at typical American budget hotels, the breakfast here is astonishing! Lovely pastries, meats, cheeses, and fresh fruits, served on china. And of course that heavenly coffee. Every time I’ve been lucky enough to travel in France I’ve found that even in bargain hotels the breakfasts are spectacular. I imagine the French simply wouldn’t tolerate anything less.

DAYS SEVEN, EIGHT, AND NINE

Another three-and-a-half-hour drive and we’re in Amsterdam, by way of Belgium. The Breitmans, who are Jewish, built a mosque here for the Turkish immigrant community.

It’s my first time in Amsterdam and I’m totally charmed. Canals, narrow streets, historic buildings, BICYCLES, trams; everything a city-lover loves.

Bike culture is unbelievable here. Even in cold, rainy January the bike lanes are bustling. Stylishly dressed riders wear no helmets. Apparently they don’t like how they look. (Okay, so that’s one thing I don’t admire about the culture here).

This town is a model of the “complete streets” we’re striving for in the U.S. Designated lanes and even signals for pedestrians, bikes, trams, and cars. Ideally this system cuts down on pollution and congestion from cars and encourages street life.

On a rare morning off, I stroll the residential neighborhoods between our hotel and the mosque. I start noticing long rows of brick apartment buildings, all the same height and with a consistent rhythm of windows, subtle modern details, and beautifully crafted modern wood doors. I go a little overboard photographing them. Later in the day I show some of my photos to Marc Breitman, and he explains that this is a style from the early 20th century known as the Amsterdam School of architecture.

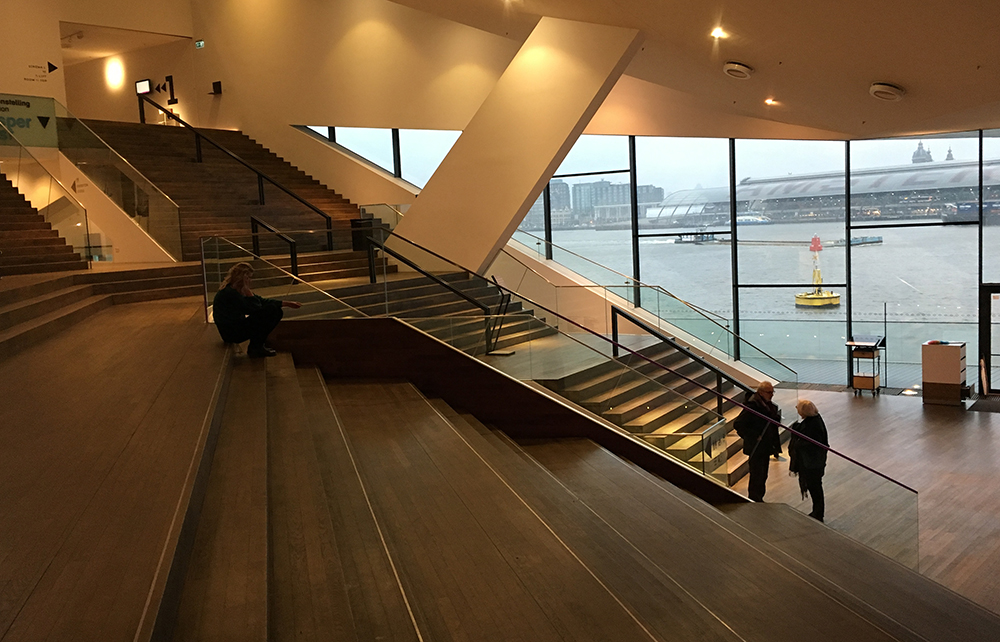

Another architectural standout (modern… sorry Marc and Nada) is the Eye Museum, the Netherlands’ national museum for film, by the Viennese architects Delugan Meissl. Its gravity-defying profile derives from the raked shape of the four movie theaters inside. It’s perched on the edge of the harbor across from the main part of the city.

Steeply sloping tiers in a glass-walled main hall double as stairs and seating for the café, so that the harbor becomes sort of a theater of life passing by through the windows. The day I visit, ferries depart from the train station every four minutes, packed with bike riders heedless of the biting wind and cold drizzle.

And oh yes… there’s FOOD in Amsterdam too. My wife (who is a real foodie) said I should be sure to sample one of Amsterdam’s famous Indonesian “rice table” restaurants – a reminder of the time when Indonesia was a Dutch colony. Dan Andries and I manage to carve out some time to visit one called Sama Sebo. If you have trouble making decisions, these restaurants are for you! The waiter brings about 30 small dishes filled with all kinds of Indonesian delights, from veggies to meats and fish and all kinds of sauces. I am NOT disappointed.

DAY TEN

Even the flight home offers some final thrills for me (aviation geek alert!). We take an uneventful short hop from Amsterdam to London. At Heathrow Airport, for some reason our 747 is not at a gate, but on a ramp out on the airfield. The result is that we are shuttled at ground level on a bus past all kinds of jumbo jets one normally only gets to see from the waiting room windows or far overhead. And then we climb a long stairway up to the door of our massive plane.

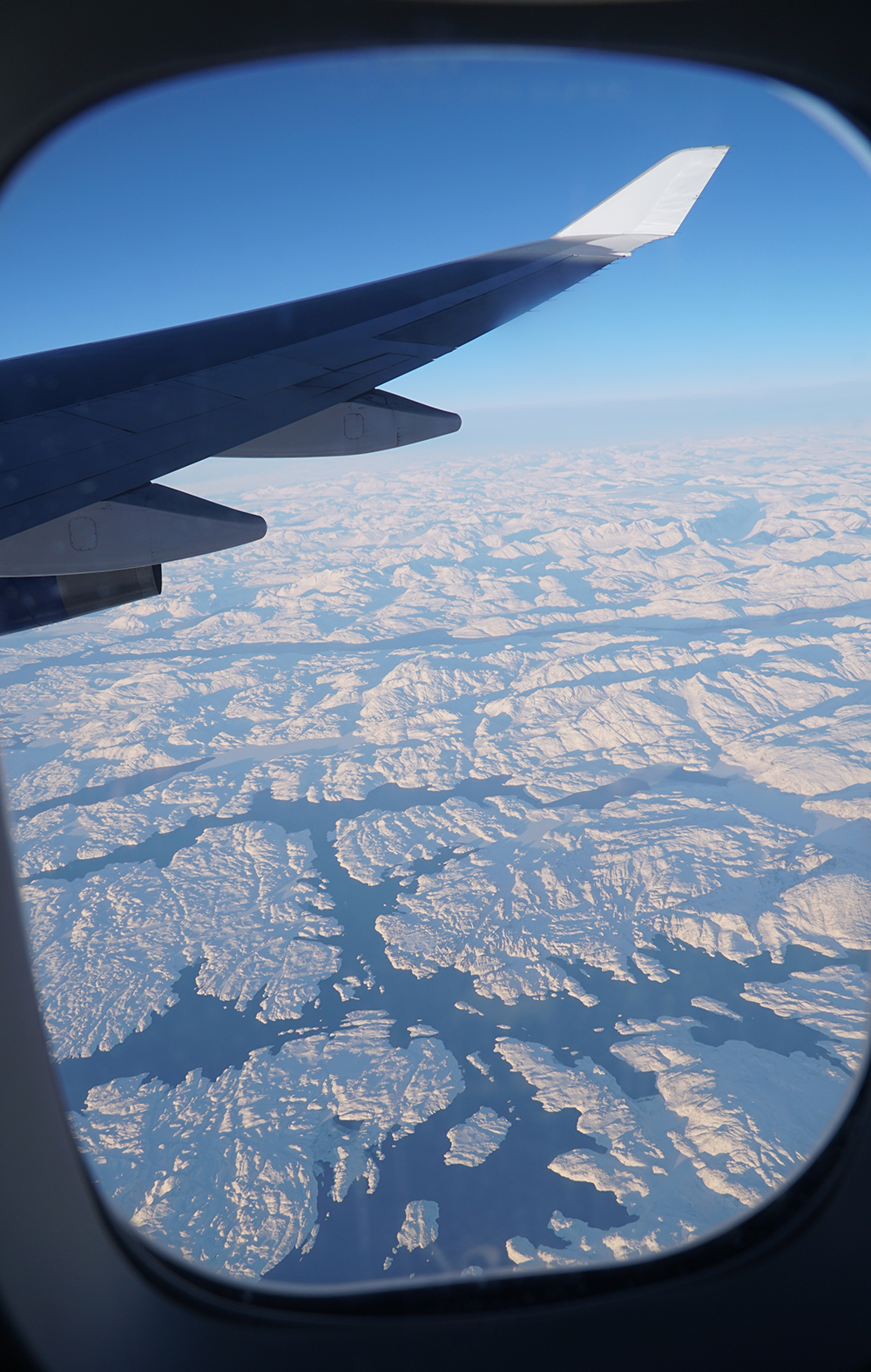

About halfway home, we fly right over Greenland. I have an aisle seat, so I’m not aware of it until I happen to check the interactive map on the video screen in front of me. I grab my camera and race to a window in the galley area. What an amazing sight to finish off an amazing trip.