On and Off the Grid

Like many cities, Chicago is laid out using a grid system. In fact, Chicago has the most orderly street grids in the world, according to the journal Applied Network Science. That’s why it looks like many of Chicago’s streets stretch out in mostly straight lines if, for example, you look north from one of the top floors of Willis Tower.

Get to know Chicago’s grid system – imperfections and all.

If you’ve ever heard people in Chicago give their location based on street addresses like “6500 south and 400 east,” that’s a way of calculating the distance from the starting point of Chicago’s grid at State and Madison streets, a.k.a. “Zero-Zero.” For the most part, every 8 blocks is about a mile.

Surveyor James Thompson created the city’s first grid in 1830 by overlaying streets on government survey lines laid out all across the country to settle the American West. He even included alleys, so we don’t have to keep our garbage on the street.

But in the late nineteenth century, Chicago voraciously annexed what were then suburbs of the city. In 1889, the city annexed more than 125 square miles, along with its 225,000 residents. But that expansion complicated things when it came to street names and numbers. For example, there were duplicate street names in different parts of the city, and sometimes streets would change names as they crossed the former boundaries of different townships.

On Chicago’s grid system, every 800 street addresses is roughly a mile. Photo: iStock.com/marchello74

Enter Edward P. Brennan, an amateur city planner. He proposed that the numbering for the grid start at zero at State and Madison. The City Council adopted his plan in 1908, and in the years that followed, Brennan helped rename streets to eliminate duplicate names and solved other issues.

Of course, things don’t always go as planned. The grid isn’t perfect, given certain natural disruptions, such as the river and, later, the construction of the city’s expressways. And some places were established before the grid system, such as one section of Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood, called “Old Bridgeport,” where streets near 31st and Halsted are angled at 45 degrees relative to the overall city grid.

Native American Trails

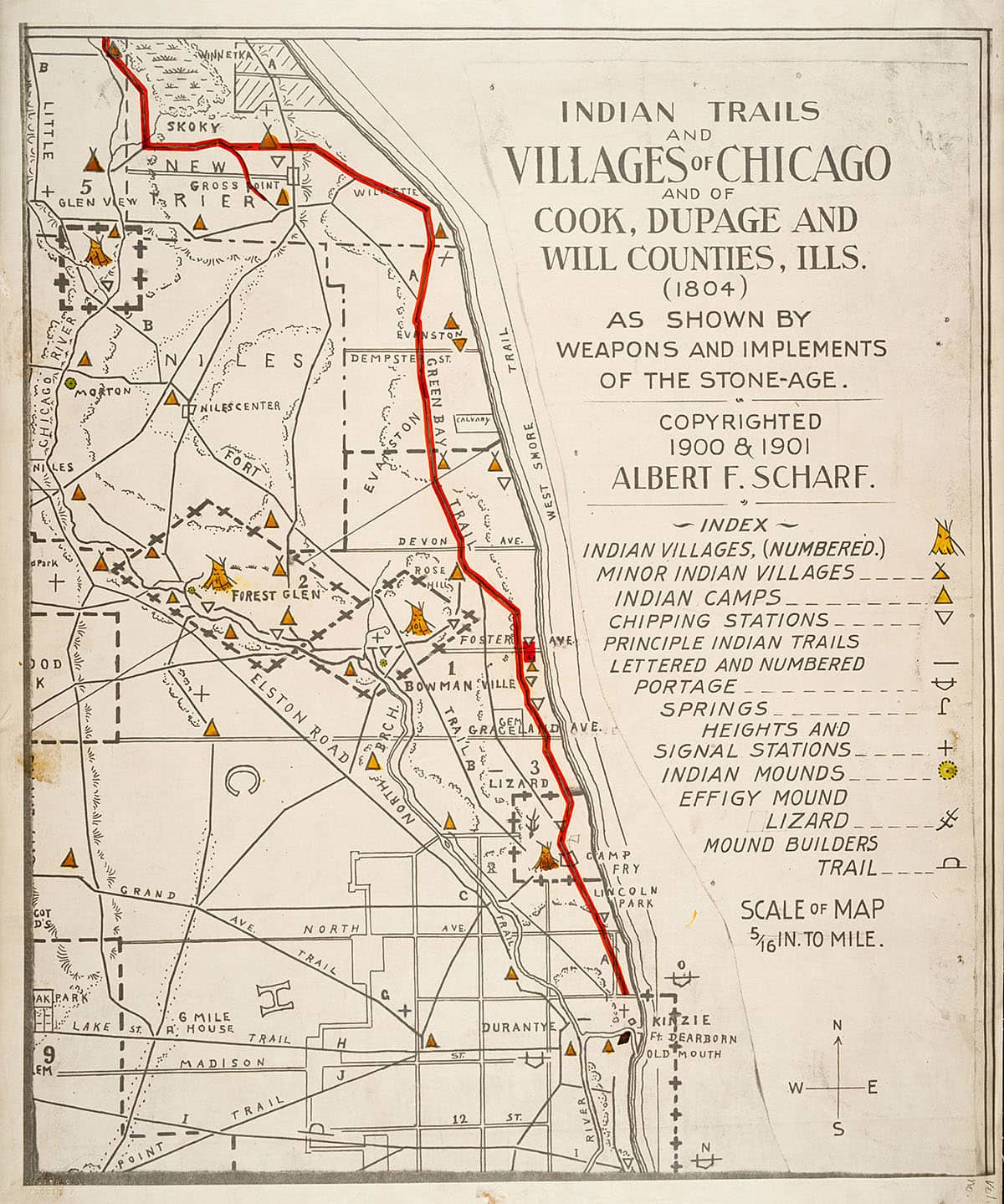

On Chicago’s grid system, every 800 street addresses is roughly a mile. Many of Chicago’s diagonal streets were once important Native American trails and trading routes. In this particular map, the Green Bay trail is highlighted in red. Image: Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum, ICHi-031997

Long before Chicago was incorporated as a city in 1837, the region was home to the Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, Miami, and other Native American nations. Various treaties, along with the Indian Removal Act of 1830, forced tribes off their land and west of the Mississippi River.

But from above, you can see many diagonal streets cutting through Chicago’s grid, revealing traces of the extensive network of trails and trade routes that Native American tribes used. Many of the trails converged near the mouth of the Chicago River, a busy trading hub hundreds of years before non-native settlers moved in.

You’ve probably traversed some of those streets: Milwaukee Avenue, Lincoln Avenue, Clark Street, Archer Avenue, Ogden Avenue, Vincennes Avenue, and more. Ice Age glaciers carved out some of these routes, leaving behind elevated ridges that allowed for easier travel through the muddy prairie.

Of course, not every diagonal street was a Native American trail. Rogers Avenue, another diagonal street on the city’s North Side, has a different story. Rogers Avenue partly follows a boundary line established by the Treaty of 1816 between the United States Government and the Potawatomi Nation. The treaty prohibited Native Americans from living on the much sought-after land near the Chicago River, reserving it for white settlers. The boundary line ran through what is today called Indian Boundary Park in the West Ridge community area. If you follow the line southwest on a map, it eventually becomes Forest Preserve Drive, which ends at Indian Boundary Golf Course.

Some of Chicago’s diagonal street corridors follow the paths of former Native American trails, which were once used for travel and trade.

A Look at Disparity from the Air

Much like Bridgeport’s angled streets or the diagonal streets that were once Native American trails, Chicago’s expressways disrupt the grid. The expressways also reflect inequities in infrastructure and housing policies.

Starting in the 1950s, many major cities across the United States and the federal government began constructing vast expressways to keep up with increased automobile use. In Chicago, the construction of the Dan Ryan Expressway and the Eisenhower Expressway displaced thousands of Chicagoans on the South and West Sides, disproportionately affecting Black, Brown, and immigrant populations.

The construction of Chicago’s expressways disproportionately affected Black, Brown, poor, and immigrant communities. Photo: iStock.com/Steve_Gadomski

Starting in the 1930s, certain discriminatory policies and practices shaped American cities in ways we can still see today. One such policy was redlining, the widespread practice in which lenders denied home loans to borrowers living in what they deemed to be “undesirable” areas, which were most often majority Black neighborhoods. You can see the red “undesirable” zones marked on maps, such as this one.

Blockbusting was another discriminatory practice. According to Richard Rothstein in The Color of Law, blockbusting “was a scheme in which speculators bought properties in borderline black-white areas; rented or sold them to African American families at above-market prices; persuaded white families residing in these areas that their neighborhoods were turning into African American slums and that their values would soon fall precipitously; and then purchased the panicked whites’ homes for less than their worth.”

From the air, the inequality between different Chicago neighborhoods is evident in everything from the tree canopy to the proximity to expressways.

Urban renewal – efforts that sought to “revitalize” cities by removing blighted or older properties – often erased entire neighborhoods in which primarily people of color lived. Sandburg Village, located in Chicago’s Gold Coast neighborhood between Clark and LaSalle streets, replaced a Puerto Rican community nicknamed “La Clark” in the 1960s. After they were displaced, many Puerto Ricans formed the Young Lords, a former street-gang-turned-political-organization that fought for the rights of Chicago’s Puerto Rican community. Sandburg Village’s buildings are oriented away from the major streets and towards a park-like courtyard to emulate a suburban feel.

From the air, vacant lots and even a lack of tree cover show the evidence of these tactics decades after they were halted. A map from the Morton Arboretum illustrates a sparse tree canopy particularly on the South and West sides as compared to more affluent neighborhoods, while a report from the Nature Conservancy reveals that “trees could help cool cities while reducing life-threatening air pollution and offering many other co-benefits for individuals and communities.”

A Suburban View

As Chicago’s expressways expanded in the mid-twentieth century, more people began to move outside of the city. Developers often designed suburban communities with curved streets to set them apart from urban life.

Chicago’s suburbs, and even some suburban-inspired neighborhoods within city limits, stand in stark contrast to Chicago’s grid system.

But some of Chicago’s early suburbs came long before the advent of the automobile, thanks to the railroad. West suburban Riverside was one of the country’s first planned suburbs, its winding streets inspired by the Des Plaines River that runs through it. Designed in 1869 by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, who created New York’s Central Park, the community has been a National Historic Landmark since 1970. According to its landmark status documentation, Riverside’s homes share similar-sized lots setback 30 feet from the road.

Riverside, Illinois was one of America’s first planned suburban communities. Photo: Bill Richert/WTTW

Suburban design can be found within Chicago’s city limits, too. Before they were annexed by Chicago in the late 1800s, Auburn Park and Norwood Park both offered a retreat from busy city life. According to the Chicago Park District, Auburn Park was once swampy marshland that developers drained in the 1880s to create a picturesque lagoon, giving the community a different feel from the urban bustle nine miles to the north. Similarly, a section of present-day Norwood Park was developed in the 1860s with the hopes of creating a resort-like atmosphere, with a subdivision between Avondale and Talcott avenues that is shaped like an oval.

One of the city’s neighborhoods takes the idea of a retreat to a whole new level. Though it’s located within the city, Old Edgebrook’s setting in the forest along a winding stretch of the North Branch of the Chicago River makes it feel far from urban life. According to the website Forgotten Chicago, railroad executives built the community as a railroad suburb in the 1890s. There were plans to build a larger community, but they never came to fruition. The Forest Preserve took the surrounding land, leaving a small island of houses tucked away in the woods. With its large homes in varying styles, Old Edgebrook is now a historic district.

Fast forward to the 1950s, when developers began bringing the suburbs into the city. South Side communities such as Scottsdale in Ashburn or Jeffrey Manor in South Deering were designed to imitate the suburban experience.

Doin' Work

Chicago has always been a city at work. In the nineteenth century, much of Chicago’s industry was concentrated near the lake and rivers. According to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, Chicago was at one time the busiest port in the nation. But as ships grew larger in the early twentieth century, the city center couldn’t accommodate them, and maritime industry shifted to the Calumet River on the South Side. Since then, waterway freight transportation has “declined significantly,” says the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning.

With its proximity to Lake Calumet and the Calumet River, the South Deering community area was at one time teeming with factories that made everything from steel to cereal. Today, much of that land is used for shipping and storage.

With its central location in the United States, Chicago was an ideal hub for rail and industry starting in the nineteenth century. Photo: iStock.com/InterCreativeSolutions

The smokestacks and pollution that used to fill the air on the South Side have now, at least in some cases, given way to greener endeavors. In the West Pullman community area, west of Lake Calumet, the Exelon energy company built what it claims is the nation’s largest urban solar plant. The 9-megawatt plant was built on a brownfield site, meaning “a property, the expansion, redevelopment, or reuse of which may be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant,” according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The solar plant can power 1,500 homes, which Exelon says is the equivalent of taking 2,500 cars off the road.

East of Lake Calumet, the Ford Chicago Assembly Plant occupies 2.8 million square feet of land in Hegewisch, just a couple of miles from the Illinois-Indiana border. The plant opened at its current location in 1924 to produce Model Ts, making it the oldest Ford assembly plant still in operation in the country, according to the company.

Chicago was built on the backs of hard-working people. Learn more about the history of industry in Chicago and how it looks different today.

All of the industry that once took up much of the Southeast Side has left behind waste in some areas, including a steel factory byproduct called slag. The EPA designated an 87-acre dumping ground for chemical and industrial waste a national Superfund site in 2010.

Reimagining Industry

Recently, some of Chicago’s industrial landscapes have been reclaimed by nature and adapted for recreation. Atop the slag near Lake Calumet, there is now a place for BMX, mountain biking, and cyclo-cross enthusiasts. Big Marsh Bike Park is a 40-acre park on existing slag fields where environmental restoration would be too hard or too expensive. It was modeled after a similar bike park in Boulder, Colorado.

Big Marsh Bike Park sits on the slag fields of what used to be industrial land. Photo: Courtesy of Friends of Big Marsh

Similar initiatives are happening all over the city. In 2016, the developer Related Midwest purchased a 62-acre patch of vacant land near the South Loop, which will be called The 78 — the name referring to the idea that it’ll be Chicago’s 78th community area when completed. The 78 will be built on what was once a large railroad yard along a bend in the South Branch of the Chicago River. That bend was straightened by moving the river 850 feet to the west between 1928 and 1930. According to the developer, the $7-billion, mixed-use development will take decades to complete. Plans include corporate offices, park space, and river access.

Some of Chicago’s former industrial sites have been reimagined over the years. Former railroads or industrial sites have become popular natural and recreational destinations.

Other former railroads have been transformed into popular recreation trails. Starting in the Dan Ryan Woods on the city’s South Side, a former rail line is now the Major Taylor Trail, a bike and pedestrian path named for Marshall W. “Major” Taylor, a celebrated, record-setting cyclist. Taylor, writes the Chicago Park District, was the son of a Black Civil War veteran. He was often banned from competing in cycling events in America because of his race, but he won several competitions in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand.

An abandoned railroad embankment in Wicker Park and Bucktown has also become a busy bike and pedestrian path called the Bloomingdale Trail, or The 606. Designed by landscape architect Michael Van Valkenbergh, who also designed Maggie Daley Park and the grounds of the planned Obama Presidential Center, the path has contributed to soaring property values as luxury homes pop up along the path, fueling a debate over gentrification in the community.

Other spaces have made use of different kinds of former industry. Palmisano Park in Bridgeport was once Stearns Quarry, a limestone quarry that opened in the nineteenth century. The quarry operated until 1970, when it became a landfill for construction debris. In 2009, it opened as a park, designed by Site Design, the same landscape architecture firm behind Ping Tom Park in Chinatown. Palmisano Park features a wetland area, a fishing pond at the bottom of the old quarry with cliff-like walls above, and a scenic hillbuilt atop the old construction debris.

At the River's Edge

The Chicago River and its surrounding areas still have traces of the city’s industrial past.

From the air, you can get a clear view of how the Chicago River and its branches wind their way through the city and its neighborhoods. One small tributary between Bridgeport and McKinley Park is a relic of Chicago’s industrial heyday — and was once a big problem. During the nineteenth century, Bubbly Creek was an open sewer, carrying animal waste and other industrial muck away from the Union Stock Yard and other factories. The decaying, unsavory contents used to literally cause the creek to bubble, giving it its name. Local legend said that Bubbly Creek was so dirty that a person could actually stand atop the stockyard waste without sinking into the water. Today, Bubbly Creek isn’t quite so dirty, but there are still ongoing efforts to clean the water.

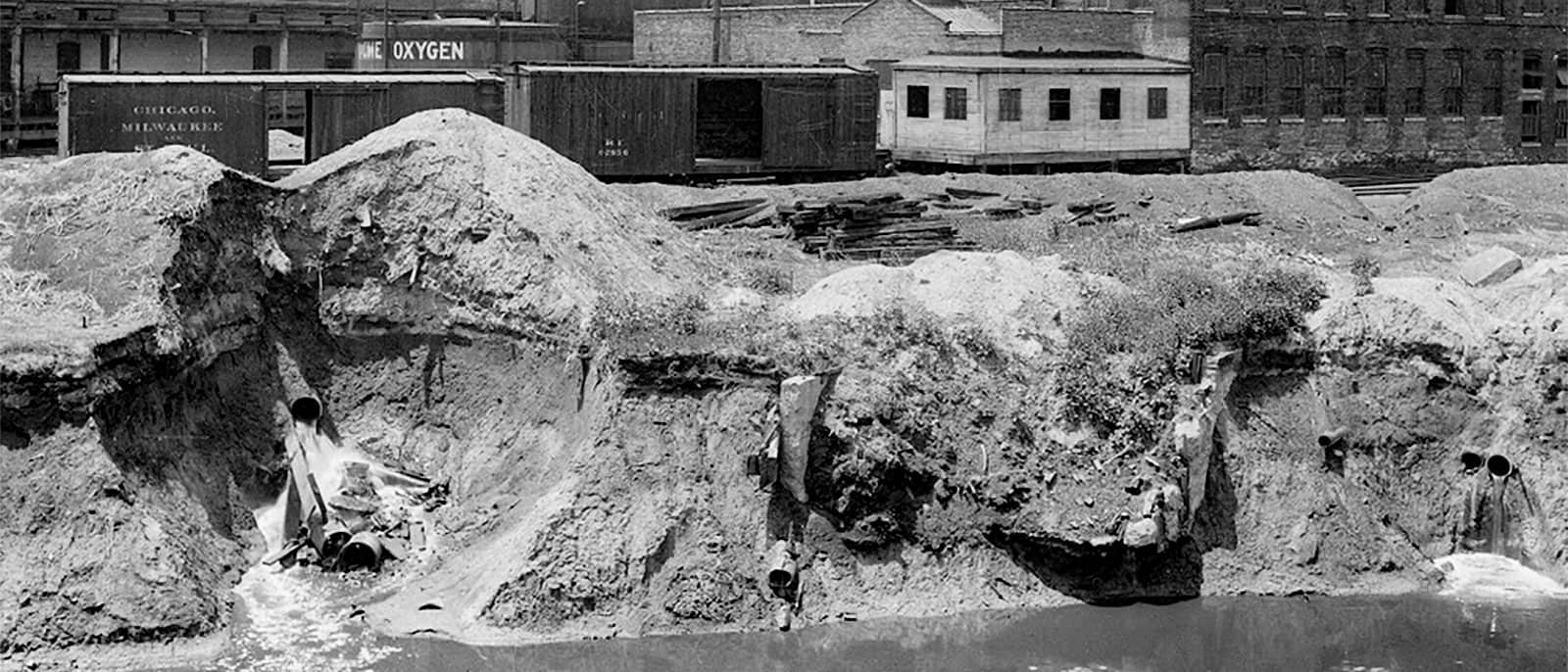

The Union Stock Yard and other factories dumped so much waste into the creek that it actually bubbled. Photo: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago

Though efforts to clean the entirety of the Chicago River continue, its history as a wastewater channel cannot be ignored. Engineers reversed the river in 1900 in an effort to steer sewage away from Lake Michigan, which is the source of the city’s drinking water. The river’s flow was redirected southwest to the Mississippi, much to the dismay of St. Louis.

Today, water treatment plants clean the water before it heads to the Mississippi River. One such plant is the Stickney Water Reclamation Plant, just north of Midway Airport. According to the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago, it is one of the largest water treatment plants in the world, serving more than 2.3 million people and treating 1.4 billion gallons of water per day. Some of the things caught in the treatment plant’s screens for larger objects? Money, a snapping turtle, a bowling ball, and “two opossums,” according to a factsheet.

On the North Branch of the Chicago River, there are other traces of the city’s industrial past. Goose Island, a man-made island built in the mid-1800s, was one of William Ogden’s many business ventures. According to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, the Chicago Land Company, of which Ogden was a major stockholder, bought the land that would become Goose Island on the North Side in 1853. Ogden, who was the city’s first mayor, dug a canal east of the river, using the clay for brickmaking and creating the island. The surrounding area became a large industrial sector, nicknamed “Little Hell” for the nearby coal gasification plants and steel mill that sent flames and smoke into the air.

The Concrete Jungle

One thing is abundantly clear from the air: Chicago has no shortage of impressive architecture, and concrete and steel are the stars of the show.

Chicago puts concrete to use in creative ways, especially in its towering skyscrapers. But for some skyscrapers, it’s metal, not concrete, that allow them to soar.

One creative use of concrete can be found in one of Chicago’s most recognizable duos: the 65-story Marina City towers. Designed by Bertrand Goldberg, Marina City was completed in 1962. According to the Chicago Architecture Center (CAC), Goldberg wanted to create a residence that allowed people to live close to work at a time when many city-dwellers were fleeing to the suburbs. “Goldberg believed that since no right angles exist in nature, none should exist in architecture,” writes the CAC, and that’s evident in the curved, corncob-like forms of Marina City — though Goldberg likened them to a sunflower.

Chicago is home to skyscrapers that come in all styles, including the new Vista Tower, pictured here on the left while under construction. Photo: iStock.com/Igor Kutyaev

You’ll also find concrete at work in the balconies of Jeanne Gang’s Aqua Tower. Each balcony in the 82-story, mixed-use building has a unique shape and size. Studio Gang claims it has one of the largest green roofs in Chicago, too. (Though you can see them only from above, more and more green roofs are popping up in the city — including on City Hall.) Gang’s new Vista Tower also puts reinforced concrete to use, as the frame for the glass exterior. Vista is now the third-tallest building in Chicago, nudging past the Aon Center.

But it was steel and iron that made skyscrapers possible in the early days. Though it’s sometimes disputed, Chicago is considered by many to be the birthplace of the skyscraper in the late 1800s, as architects and engineers discovered that steel or iron frames — such as that in the Reliance Building, with its terra cotta exterior, completed in 1895 — were ideal for supporting tall buildings, rather than thick stone or brick walls. Similarly, the Merchandise Mart and Burnham Center might look like stone and terra cotta, respectively, on the outside, but the frames inside are steel.

Steel made its exterior debut in the 1950s, when architects such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe designed buildings to show off their structure. This can be seen in his AMA Plaza, completed in 1972. Of course, the most prominent example is Willis Tower (formerly known as Sears Tower) — Chicago’s tallest building, reaching 1,450 feet, or 110 stories, into the sky.

Urbs in Horto

When Chicago was incorporated in 1837, it adopted as its motto the Latin phrase Urbs in Horto, which means “City in a Garden.” But that motto may have been more aspirational at the time, as the city lacked much green space in its early days.

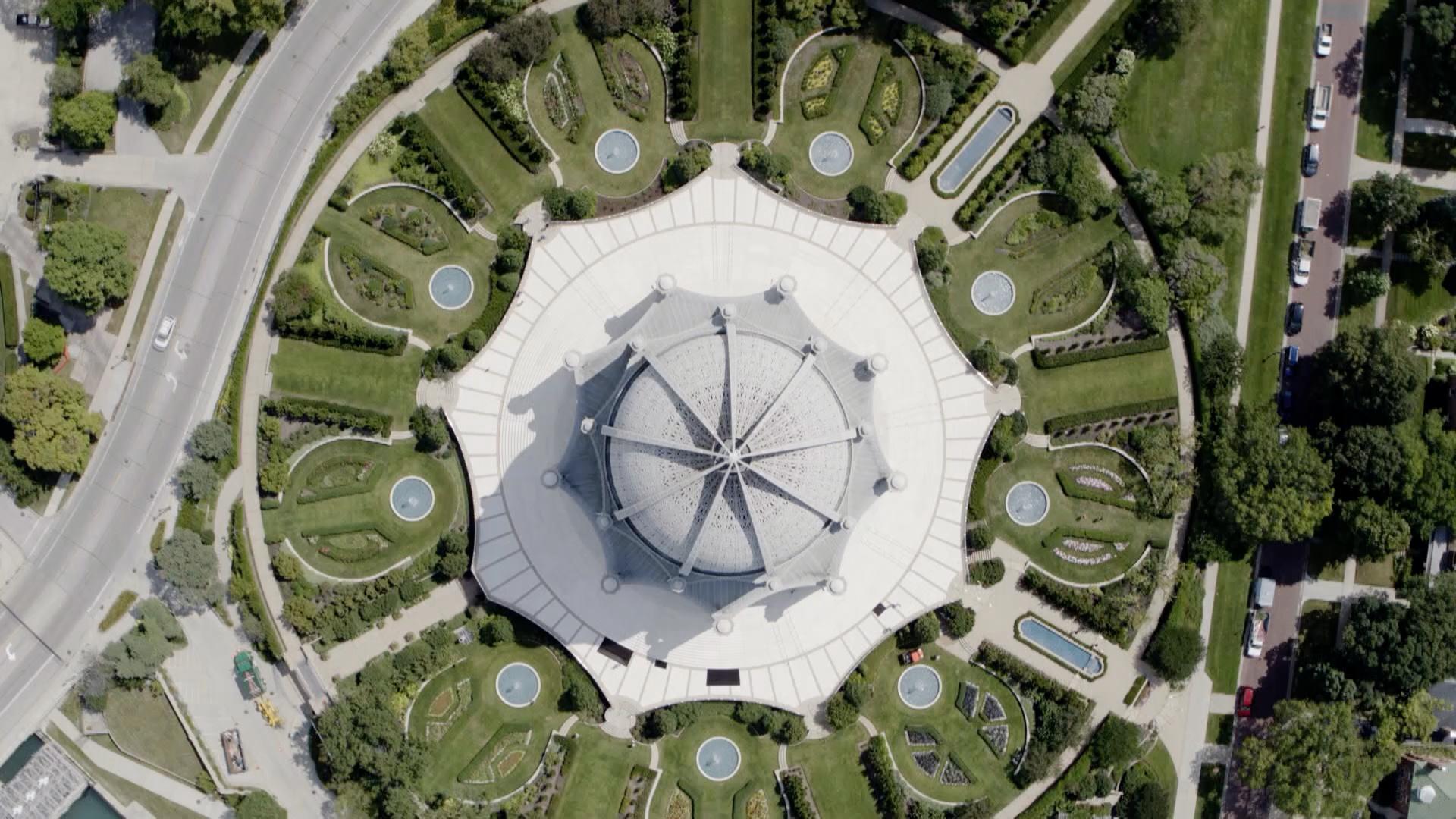

As Chicago grew, so did the need for parks and other green space. In the early twentieth century, some of the city’s leaders were worried that rapid urban growth would overtake the area’s natural beauty. According to the Forest Preserves of Cook County, landscape architect Jens Jensen, architect Dwight Perkins, and city planner Daniel Burnham played key roles in fighting for a permanent forest preserve system. In 1914, the Forest Preserve District of Cook County was established, and two years later, its first section of land was set aside in what would become Deer Grove, northwest of Chicago. The Skokie Lagoons, once a marsh, became what they are today with human intervention. In the 1930s and ’40s, workers reconfigured the land to createartificial lagoons. The Chicago Botanic Garden in Glencoe is perhaps the best-known land operated by the Forest Preserves. The 385-acre garden opened in 1972 and includes 27 gardens, nine islands, and four natural areas.

On the South Side, one 593-acre park embodies Chicago’s early commitment to becoming a city in a garden. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux designed Jackson Park in 1871; they “envisioned an interconnected system of waterways, lushly planted and accessible from Lake Michigan,” according to the Cultural Landscape Foundation. In 1893, it became the site of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Olmsted and Daniel Burnham designed the fair’s temporary “White City” as a neoclassical dreamland, with waterways, pavilions, gardens, and art. Though the original Statue of the Republic that stood in the Court of Honor is gone, a replica of the statue that’s roughly one-third of the size of the original is near the original’s location.

The Statue of the Republic is a replica of the original Daniel Chester French sculpture that stood at the Court of Honor at the World’s Fair. This 24-foot statue is one-third the size of the original. Photo: Alan Brunettin/WTTW

Most of the fair’s structures are long gone, but the Museum of Science and Industry remains. During the fair, it served as the Palace of the Fine Arts, and was therefore built as a sturdy brick structure to protect the valuable works of art within, unlike the other fair buildings which were covered in plaster. After the fair, the building became the first site of the Field Museum, and was vacant from 1920 to 1933, when the Museum of Science and Industry moved in.

The Fair’s Wooded Island also remains. Nestled between the park’s east and west lagoons, Olmsted intended for the island to offer a peaceful retreat from the bustle of the fair, much as the park itself was designed to be a respite from the city, writes the Chicago Park District. During the fair, Wooded Island was the location of the Japanese Pavilion, which was burned down in an act of arson when anti-Japanese racist sentiment was high after World War II. But today, the Osaka Garden, also referred to as the Garden of the Phoenix, preserves that heritage and stands as a symbol of Chicago’s relationship with its sister city in Osaka, Japan. In 2016, artist Yoko Ono installed the Skylanding sculpture just outside the Osaka Garden. The sculpture emulates lotus petals and stands as a symbol of peace.

But Jackson Park is just one piece of the puzzle. It is part of a network of South and West Side parks developed in the nineteenth century and connected by a boulevard system. On the West Side, leafy boulevards connect Garfield, Humboldt, and Douglass parks, all of which were designed by William Le Baron Jenney. As if that’s not an impressive enough resume, Jenney is also credited as the father of the skyscraper. In the early 1900s, landscape architect Jens Jensen added his touch to the parks, adding native plants to the design which came to be called the Prairie Style. Jensen also designed the Garfield Park Conservatory, one of the largest greenhouses in the world.

From the beginning, Chicago’s motto has been Urbs in Horto, which is Latin for “city in a garden.” Today, the city’s parks and greenery still seek to fulfill that motto.

A Spiritual Journey

A view from the air uncovers the diversity of Chicago’s faith communities and their grand houses of worship. In Wilmette, the Bahá’í House of Worship soars 190 feet over the Wilmette Harbor. The Bahá’í faith was founded in the mid-1800s in present-day Iran and emphasizes the oneness of humanity and all religions under a single God. The temple combines various forms of architectural style, including a Renaissance dome and intricate Gothic ribbing.

Farther north on the lakefront, you’ll find North Shore Congregation Israel, a reform Jewish synagogue. The congregation acquired the property in the 1950s. Renowned architect Minoru Yamasaki — who also designed the original World Trade Center towers in New York City — designed the mid-century modern building.

The Bahá’í House of Worship is decorated with the religious symbols of Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, Islam, and Christianity. Photo: Courtesy of the Bahá’í House of Worship

In one southwest suburb, an Islamic prayer center pays homage to the famous Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. The Prayer Center of Orland Park opened in 2006. The three-story, 22,000-square-foot mosque features a golden dome, eight-sided design, and arched entrance, similar to its inspiration in Jerusalem, according to its website.

The many houses of worship in Chicago and the surrounding communities add to the city’s beauty and diversity.

In west suburban Bartlett, the BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir offers another ornate example of Chicagoland’s spiritual community. According to its website, “Mandir is a word of Sanskrit origin and it means the dwelling place for the Deities.” More than 1,700 volunteers from three continents donated their expertise during the temple’s construction. The building was shipped in 40,000 different pieces from India after 3,000 artisans chiseled the traditional, intricate patterns into the stones.

In Chicago, there is certainly no shortage of churches. In Bucktown, 26 angels adorn the dome — inspired by St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome — of St. Mary of the Angels. Dedicated in 1920, the church structure was designed in the Renaissance style. That style, along with baroque, was popular for the city’s many Polish churches, sometimes called “Polish Cathedrals.” St. Stanislaus Kostka Parish in Wicker Park is another example of that style. It was almost torn down in the 1950s during the construction of the Kennedy Expressway, but the parish fought to reroute the expressway so the building wasn’t demolished.

In the Loop, First United Methodist Church of Chicago at the Chicago Temple combines the spiritual with the professional. The church has been located on the corner of Washington and Clark streets in one building or another since 1838. In 1924, the combination office building and house of worship was built, and its 23 floors make it a skyscraper. It has a chapel at the base of its towering spire, one of three sanctuary spaces in the building.

A church on the Near South Side is home to the city’s oldest Black congregation. According to the Chicago Public Library, Quinn Chapel A.M.E. Church started as a prayer group of seven people in 1844, and the church’s first congregants were mostly formerly enslaved people and abolitionists. It was also a stop on the Underground Railroad. Throughout its long history, Quinn Chapel A.M.E. Church has hosted many prominent speakers, including Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, Susan B. Anthony, and former President Barack Obama.

The Lakefront

From the air, you can trace the edge where the bright blue waters of Lake Michigan meet the concrete, sand, and green of Chicago. Nearly all of that coast is a manmade park — the 18-mile Lakefront Trail was part of the larger vision of Daniel Burnham and Edward H. Bennett’s 1909 Plan of Chicago, also known as the Burnham Plan.

One of Chicago’s signature landmarks is its lakefront park along Lake Michigan. It was all part of the 1909 Plan of Chicago.

According to the Chicago Architecture Center, the Burnham Plan was “a visionary Progressive Era proposal that sought to beautify Chicago and improve efficiency of commerce” at a time when Chicago was overcrowded and dirty. Burnham, who was already respected for overseeing the World’s Columbian Exposition, worked with Edward H. Bennett to create the plan, which focused on six key areas: lakefront improvement, building a highway system, improving railroad terminals, creating a park and parkway system, reconfiguring city streets to suit the needs of downtown, and creating centers for civic life. It took years to implement many of these, and not all were fully realized. But the 1909 Plan of Chicago is still referenced in urban design today, and the preserved lakefront stands as the most recognizable achievement from the plan.

Chicago’s beloved lakefront, including the “athletic grounds” where Soldier Field now stands, was all part of the 1909 Plan of Chicago. Photo: iStock.com/marchello74

In recent years, lakefront access has been updated and improved. The 35th and 41st Street pedestrian bridges gave South Siders direct access to the lakefront, which for years had been blocked by Lake Shore Drive and the Illinois Central Railroad, allowed by the city to take up valuable lakefront property in the 1860s. Senator Stephen A. Douglas provided the land grant for that railroad, since it came up the lakefront and passed his property. Douglas, who was the owner of enslaved people, is entombed on that property at the base of a column topped by a statue of him overlooking the historically Black neighborhood of Bronzeville. Recently, there have been calls to remove the statue.

Burnham envisioned a series of manmade islands between Grant and Jackson parks. Just south of downtown, a small part of that vision came true — partially, anyway. The 119-acre Northerly Island was the only portion of the island chain ever to be built. Chicago’s second World’s Fair, the Century of Progress, took place on Northerly Island in 1933-1934. The island was also the location of a small airport called Meigs Field from 1947 until 2003, when the city decided to return the island to park land. Mayor Richard M. Daley had bulldozers secretly and infamously carve “X’s” into the runways overnight. It took years, but today, it’s a natural area with prairie grasses, rippling hills, and views of the city.

Just a stroll from Northerly Island are two significant landmarks: Soldier Field and the Museum Campus. The Burnham Plan conceived of “athletic grounds” where Soldier Field stands today. In 1996, the northbound lanes of Lake Shore Drive were moved to the west, forming the “campus” where the Field Museum, Shedd Aquarium, and Adler Planetarium all live. Prior to 1996, the Field Museum was isolated in a kind of island between the north- and southbound lanes of Lake Shore Drive.

Chicago's Front Yard

Like much of the Chicago lakefront, Grant Park is a man-made gem. Grant Park’s early days can be traced back to as early as 1835, when citizens lobbied to keep the areaan open, public space. In 1847, it was known as Lake Park, but the Illinois Central Railroad ran past the area on a trestle 300 yards out into the lake, creating stagnant water between the trestle and the shore.

Grant Park is the product of a decades-long fight to preserve open, public park land along the lakefront. Photo: iStock.com/Brunomili

After the Great Chicago Fire, the water between the trestle and the shore became a dumping ground for ashes and rubble from the fire, creating a new parcel of land. At this point, Lake Park could hardly be called a park. In 1901, it was renamed for President Ulysses S. Grant, and Chicago businessman Aaron Montgomery Ward embarked on a 20-year legal battle for the soul of that land, forcing the city to transform it into a park. Over time, the railroad tracks were lowered below grade, and the park was built out further into the lake.

Grant Park is Chicago’s front yard, and like the lakefront, it’s an entirely manmade natural wonder. It was also the battleground for the fight to reclaim the lakefront for the public.

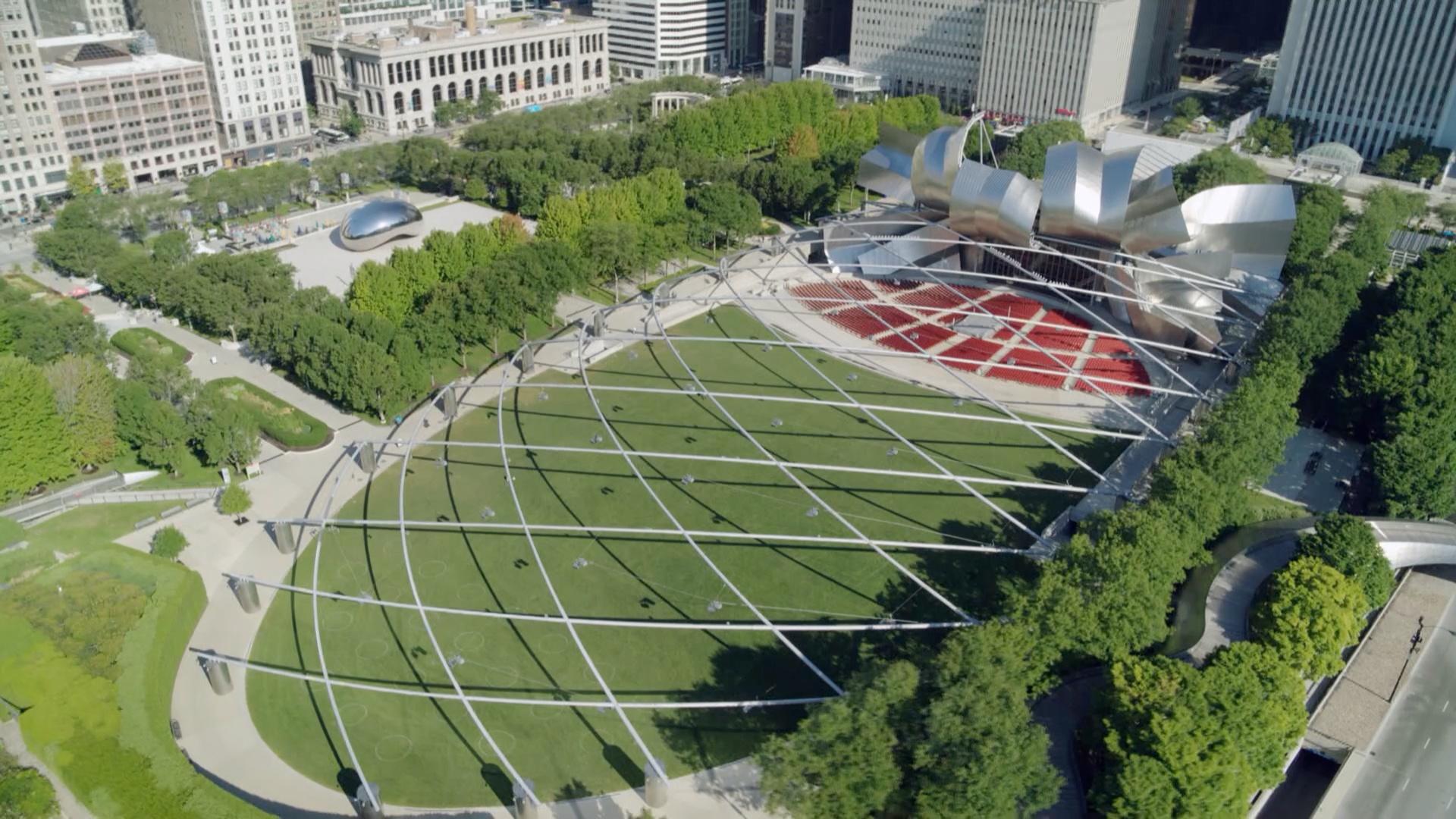

Today, the sprawling 312-acre park includes athletic fields, tennis courts, and gardens, and is home to festivals such as The Taste of Chicago and Lollapalooza. The park’s focal point is Buckingham Fountain. Built in 1927, the fountain features a water display every 20 minutes during the warmer months. Also near Grant Park are Maggie Daley Park, The Art Institute of Chicago, and Millennium Park. Completed in 2004, Millennium Park is a popular destination for visitors and includes such attractions as Cloud Gate (or, the Bean), Pritzker Pavilion, the Crown Fountain, and the Lurie Gardens.