Can We Swim in the River Yet? | The Chicago River Tour with Geoffrey Baer

Courtesy of Metropolitan Water Reclamation District

Can We Swim in the Chicago River Yet?

On a warm, September day at Ping Tom Memorial Park in Chicago’s Chinatown, more than a dozen local, state, and federal officials signed waivers, put on life jackets, and lined up along the edge of the Chicago River, ready to jump in.

They laughed, posed for the cameras, and looked down at the rotten leaves floating along the top of the slow, murky waters. Several rescue boats sat in the river, ready to spring into action if anything went wrong, while downstream, near the site of what was once the largest slaughterhouse in the world, gasses from decades-old carcasses and other industrial waste bubbled up to the surface.

Swimming in the Chicago River has been a running joke in this city for nearly half a century, ever since the late Mayor Richard J. Daley proclaimed his desire to “see the day there will be fishing in the river…perhaps swimming.”

The city erupted in laughter. But since that time, a lot has changed.

The 1972 Clean Water Act established water quality standards and a system of accountability for all pollutants discharged into national waterways and gave local environmentalists a set of tools with which to hold industries and government agencies accountable.

In recent decades, a coalition of local and national environmental groups – including Friends of the Chicago River, the Environmental Law and Policy Center, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and others – has banded together to do just that.

Their efforts have transformed the Chicago River.

A young angler gets help from a Chicago Park District fishing instructor during #ChicagoFishes event in October 2017. Courtesy of Shedd Aquarium

Now, on a sunny, summer day, local families and tourists vie for space in kayaks, yachts, and rented pontoons on the river’s Main Branch, while along the shore, fishermen cast their lines, and groups of friends sip wine, sitting close enough to dip their toes in the water.

And then there are the politicians, who will jump in the water just to drive the point home.

But how safe is it, really, to swim in that stuff?

The answer is complicated, for several reasons. First, though many portions of the Chicago River are manmade, it is still a moving body of water, filled with living organisms and aquatic wildlife. It will never be as clean as, say, a pool. Second, the river and its branches comprise 150 miles of waterways. There are many different stories – past and present – along different stretches along the river: century-old pollutants that have settled on the bottom, chemicals and bacteria that survive the wastewater treatment processes, and runoff and raw sewage that sometimes enters the waterways during rainstorms.

The most serious threat to human health in the Chicago River is fecal coliform: a bacteria that typically originates in the intestines of humans and other warm-blooded animals. E. coli is one type of this bacteria. Scientists sometimes use fecal coliform to predict the presence of a whole host of waterborne diseases, including typhoid fever, hepatitis, gastroenteritis, and dysentery. Public health officials say that no human should swim in any body of water with high levels of fecal coliform. Doing so can make you sick, whether by accidentally swallowing the water or from pathogens entering the body through cuts, sinuses, or other entry points.

Outfall warning sign Courtesy of Eric Allix Rogers/Flikr

The good news is that improvements over the past several years have reduced the fecal coliform count along much of the Chicago River to safe levels – most of the time.

How Poop Gets into the River (And Sometimes the Lake)

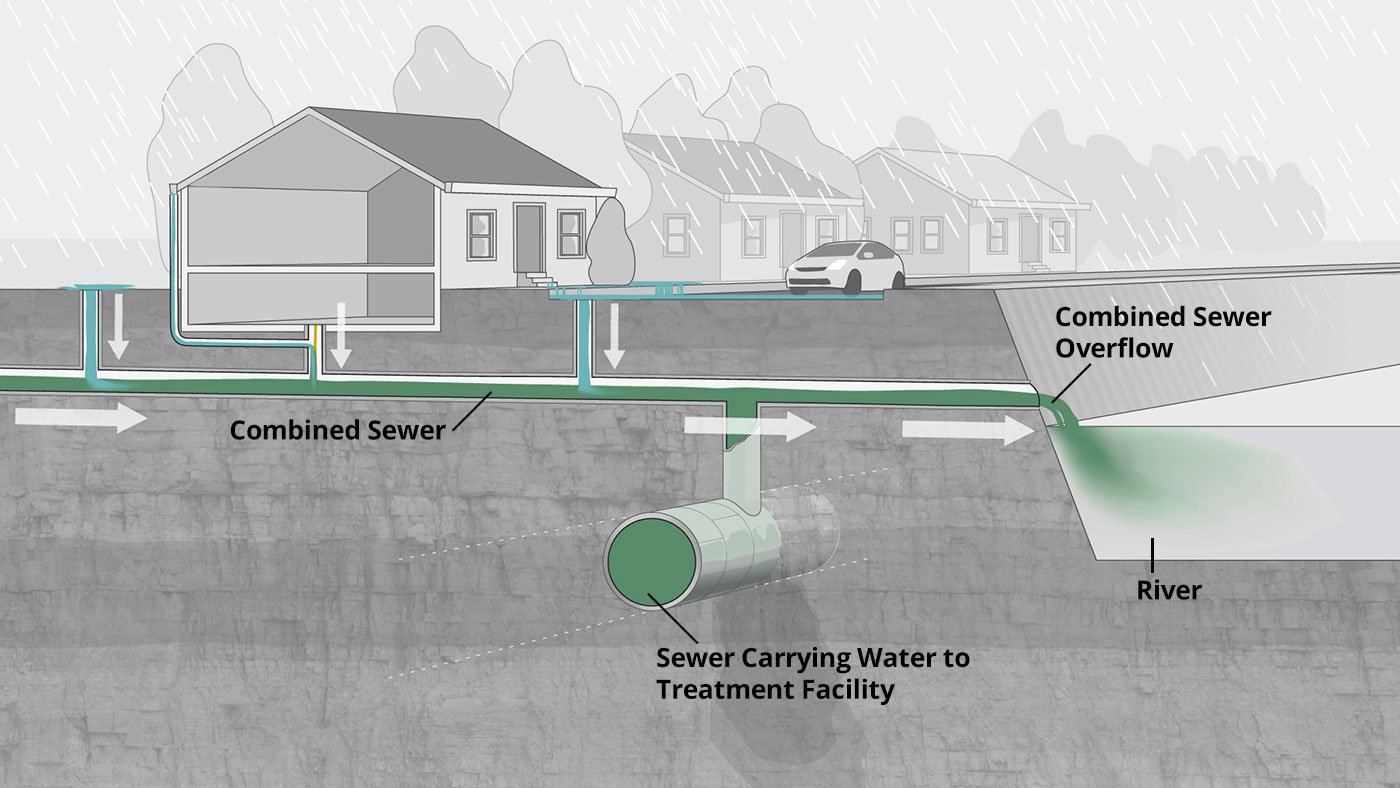

The largest source of fecal coliform in the Chicago River is the city’s combined storm-sewer system, which was designed in the 1850s, when freshwater was a seemingly endless resource, major rainfall events were less frequent, and the population was a fraction (literally one hundredth) of what it is today. The biggest threats to the city’s future at that time were the swampy marshland that the city was built on and the cobbled-together sewer system, which employed things such as open oak gutters to carry away Chicago’s waste.

So, engineers designed a system that would solve both problems by carrying both storm water and sewage through the same underground pipes into the river.

Feature: How Chicago Reversed Its River — An Animated History

Learn the story of how, more than 100 years ago, Chicagoans pulled off one of the most audacious engineering feats in U.S. history.

Over time, that network was improved. The river was reversed so that sewage would be carried away from Lake Michigan (the source of our drinking water) instead of toward it. As technology advanced, additional pipes were laid to reroute the rain and wastewater to treatment plants where it could be filtered before entering local waterways.

But to this day, whenever there is a heavy rain, the aging labyrinth of sewer lines gets overwhelmed. The noxious stew of rainwater, runoff, and all of the slop dumped down regional drains gets backed up, flows into those old pipes, and empties into the river. This is called a “combined sewer overflow,” or CSO (not to be confused with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra).

Courtesy of Metropolitan Water Reclamation District

When it really pours, the locks and gates that slow the flow of Lake Michigan into the river are thrown open and Chicago’s sewage flows directly into the lake, just like old times. Nearly 40 billion gallons of sewage-laden river water has been released into Lake Michigan during CSOs since 2000, more than half of it from the Main Stem.

The $4 Billion Fix

Through much of the twentieth century, urban sprawl and a growing population combined to increase the amount of wastewater produced in Cook County, decrease the amount of greenspace, and further increase frequency of CSOs.

By the late 1960s, sewer overflows were taking place an average of 100 days per year, according to the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD), the regional wastewater treatment agency that deals with wastewater from Chicago and its environs. State, county, and city representatives decided that something had to be done, so they devised a system of deep tunnels and reservoirs that would hold excess water until the MWRD’s treatment plants could process it.

Construction on the Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP), or Deep Tunnel, began in 1975. The first portion of the massive underground system began functioning in 1981. Portions of the system are still under construction. When it is completed in 2029, at a cost of $3.8 billion, it should be able to hold up to 20.55 billion gallons of excess water.

Combined Sewer Overflows, Central Chicago Waterways, 2007-2016

Volume of CSOs in Main and McCook TARP Service Areas, which have not yet been completed

| Year | CSO volume (billions of gallons) | Number of CSO days | Precipitation (inches) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 12.45 | 40 | 25.6 |

| 2008 | 28.44 | 46 | 38.6 |

| 2009 | 14.93 | 67 | 35.4 |

| 2010 | 71.72 | 51 | 32.8 |

| 2011 | 29.92 | 57 | 25.0 |

| 2012 | 87.35 | 27 | 18.7 |

| 2013 | 31.15 | 65 | 26.5 |

| 2014 | 19.60 | 70 | 31.5 |

| 2015 | 15.49 | 36 | 29.1 |

| 2016 | 13.65 | 51 | 21.3 |

Waterways included in the above data include the North Shore Channel, North Branch of Chicago River, Chicago River, South Branch of Chicago River, Bubbly Creek, Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, Des Plaines River, and Addison Creek, according to the MWRD. Precipitation is measured by total rainfall at Stickney Water Reclamation Plant.

Still, even in the areas where it is fully operating, TARP hasn’t managed to completely eliminate sewer overflows. And given the increasing prevalence of intense, fast-moving storms, even the MWRD now says that it’s unlikely Deep Tunnel will be able to completely solve Chicago’s sewage overflow problem in the future.

Combined Sewer Overflows, Southern Chicago Waterways, 2007-2016

Volume below for Calumet TARP Service Area, which became fully functional in November 2015

| Year | CSO volume (billions of gallons) | Number of CSO days | Precipitation (inches) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 3.05 | 16 | 39 |

| 2008 | 8.43 | 21 | 45.6 |

| 2009 | 3.74 | 27 | 43.3 |

| 2010 | 10.34 | 19 | 40.7 |

| 2011 | 5.65 | 18 | 44.1 |

| 2012 | .74 | 6 | 27.8 |

| 2013 | 4.02 | 22 | 43.2 |

| 2014 | 2.98 | 24 | 44.1 |

| 2015 | .55 | 9 | 37.6 |

| 2016 | .004 | 1 | 34.6 |

Waterways that will be served by the Calumet Tunnels include the Calumet River, Grand Calumet River, Little Calumet River, Cal-Sag Channel, and the Calumet-Union Drainage Ditch. Precipitation is measured at the Calumet Water Reclamation Plant.

The Answers in Our Backyards

One solution is to stop so much of the water from reaching the combined-sewer system in the first place. To that end, the MWRD, city planners, and local environmentalists are promoting green infrastructure – things such as rain gardens, permeable pavement, and open space that will allow rainwater soak into the ground rather than run into the gutter.

In recent years, the MWRD has also joined Friends of the Chicago River and other groups in raising awareness about the role residents can play to reduce flooding by proactively conserving water during rainstorms.

Disinfecting the Sewage for a Cleaner River

When there hasn’t been a recent storm, the Chicago River is actually much safer to swim in than it was just a few years ago. That’s because approximately 70 percent of the water in the river comes directly from the wastewater treatment plants, and that wastewater just got a lot cleaner.

In 2016, following years of pressure from Friends of the Chicago River, the Environmental Law and Policy Center, Openlands, and other regional environmental organizations, the MWRD implemented disinfection technology at two of its seven treatment plants. The upgraded treatment process has resulted in a dramatic reduction in bacteria levels downstream from the Calumet and O’Brien treatment plants, where disinfection has been implemented during the nine warmest months of the year, when the MWRD expects residents to be recreating on or along the waterways.

Fecal Coliform Readings During Routine MWRD Monitoring

Samples taken at Touhy Avenue on the North Shore Channel, 0.5 mile downstream of the O'Brien Water Reclamation Plant

| Month collected | CFU/100mL |

|---|---|

| March 2015 | 4400 |

| April 2015 | 12000 |

| May 2015 | 4400 |

| June 2015 | 3400 |

| July 2015 | 7200 |

| August 2015 | 11000 |

| September 2015 | 7900 |

| October 2015 | 25000 |

| November 2015 | 10000 |

| December 2015 | 20000 |

| January 2016 | 5300 |

| DISINFECTION BEGAN | |

| March 2016 | 220 |

| April 2016 | 100 |

| May 2016 | 50 |

| June 2016 | 99 |

| July 2016 | 150 |

| August 2016 | 99 |

| September 2016 | 20 |

| November 2016 | 380 |

| December 2016 | 31000 |

| January 2017 | 5900 |

| February 2017 | 4200 |

| March 2017 | 100 |

| April 2017 | 100 |

| May 2017 | 210 |

| June 2017 | 490 |

| July 2017 | 220 |

| August 2017 | 260 |

The above data show fecal coliform counts during routine MWRD monitoring. On at least five occasions between March 2016 and September 2017, additional samples taken following rainstorms showed fecal coliform counts above 200, the EPA’s 1986 limit for recreational waters. On one occasion, in June 2017, a sample showed 360,000 CFU/100mL of fecal coliform, or 1800 times the legal limit for recreational swimming. In 2017, disinfection took place between March 1 and November 30 at both Calumet and O'Brien treatment plants. By Jessica Pupovac

“It’s exciting to watch this progression, and we think it’s snowballing, and it is only going to get better,” Stacy Meyers, staff attorney with Openlands, told WTTW. “With a growing recognition of our community responsibility to manage storm water, disinfection coming online, beautiful projects that are improving access to our riverfront…people are seeing Chicago’s ‘second shoreline’ as a real gem for the whole region.”

Other Nasty Things in the Water

But we shouldn’t put on our swimsuits just yet – not even during dry spells. That’s because while fecal coliform is on the decline, it isn’t the only contaminant that isn’t good for humans to come in contact with or accidentally ingest.

One pervasive problem is the toxic chemicals that people put down their drains. To put it simply, at most Chicago-area treatment plants, two things happen. First, solids are filtered out. Then, microorganisms – or tiny, microscopic bugs – eat the actual organic matter, or what’s left of the poop, before the water is released into local waterways. The new, third step – disinfection – kills the fecal coliform that all of that poop left behind.

But most pharmaceuticals, paint thinner, household cleaning products, and other chemicals that people pour down their drains still make it through the treatment process and wind up in the river. They probably won’t make humans immediately ill, but they might not be good for us.

Allen LaPointe, vice president of environmental quality at the Shedd Aquarium, says that most people don’t realize that a lot of what we put down our drains winds up in the river.

“The wastewater treatment process is really not designed, in most cases, to remove all of these pollutants,” said LaPointe. “You should not use the drain for waste, period.”

Feature: Six Ways You Can Help the Chicago River

The biggest obstacle to a cleaner river is us — the millions of humans who live along the river’s vast watershed. Here are some ways to make your impact a positive one.

Another source of river pollution is runoff – all of the road salt, oils, and chemicals that are on our roads. Those flow directly into the river, either through storm drains that empty into the river or through surface water flowing downhill.

Last but not least, there are several legacy pollutants that still lurk on the bottom of the river – from the glue-making factories, tanneries, and meat-processing plants that used to line the Chicago River back in the city’s industrial heyday. As the river gets cleaner, government agencies and advocates will be more able to pinpoint where those hazards remain and develop comprehensive proposals for remediating them.

Should Swimming in the River Be a Goal?

A spokesperson for the MWRD said that while there have been significant improvements in cleaning area waterways in recent years, some of the problems aren’t going away any time soon.

“Although water quality is improved, many hazards exist on the waterways due to boat traffic, currents, temperature and lack of ingress and egress, to name a few,” the MWRD said in a statement. “In short, the CAWS [Chicago Area Waterways] is not designed for swimming.”

Indeed, many portions of the waterways were built specifically to be used as shipping canals or dock slips. But advocates of a swimmable river say that is just one more obstacle to overcome.

“If it’s connected and it’s water and there’s fish in it, it doesn’t matter whether you dug it or not,” said Margaret Frisbie, the executive director of Friends of the Chicago River. “It is all part of our waterways now, and it needs to be protected, cleaned up, and made accessible.”

Frisbie pointed to legally binding, water quality standards that legally require key portions of the Chicago and Calumet Rivers to be clean enough to swim in. The Illinois Pollution Control Board adopted the new standards in 2011 at the urging of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, in accordance with the Clean Water Act.

In reality, they aren’t always clean enough for swimming, said Frisbie – but they are supposed to be. And, most importantly, they are constantly improving.

“We’re used to talking about its history of pollution and neglect. But the Chicago River is cleaner than you think it is,” she said. “Most of the time, for most of the people, the river is fine.”

What she calls the “cultural barrier” to coming into contact with the river – the generations-old fear born of knowing the river’s industrial legacy – is also changing, albeit slowly.

“People’s perceptions of the river have changed dramatically,” said Frisbie. “People think things are possible that they never thought were going to happen in a million years.”

Margaret Frisbie, executive director of Friends of the Chicago River, participated in the Big Jump at Ping Tom Memorial Park in September 2017. Photo by Kaitlynn Scannell

Frisbie believes that, in the near future, there could likely be more widespread interest in cordoning off portions of the river for swimmers, adding infrastructure such as ladders and life rings, and warning the public about the occasional bacterial hazard – much as is the current practice along Chicago’s lakefront beaches.

“They have a flag system, a hotline, and a web site,” she said. “If you want to swim, you can find out from your home whether or not it’s a good day for it.”

The MWRD is already monitoring sewer overflows and has an online notification system to alerts residents when they occur, so Frisbie says the capability is there – we just need the collective will, and investment, to make it happen.

“Not only do we still need to figure out any other sources of pollution that may make people sick, but we need to convince local government that we want and deserve to swim here,” she said.

And, as Chicagoans come to see their river as more of an asset than a liability, more are asking not if, but when we can all jump in.