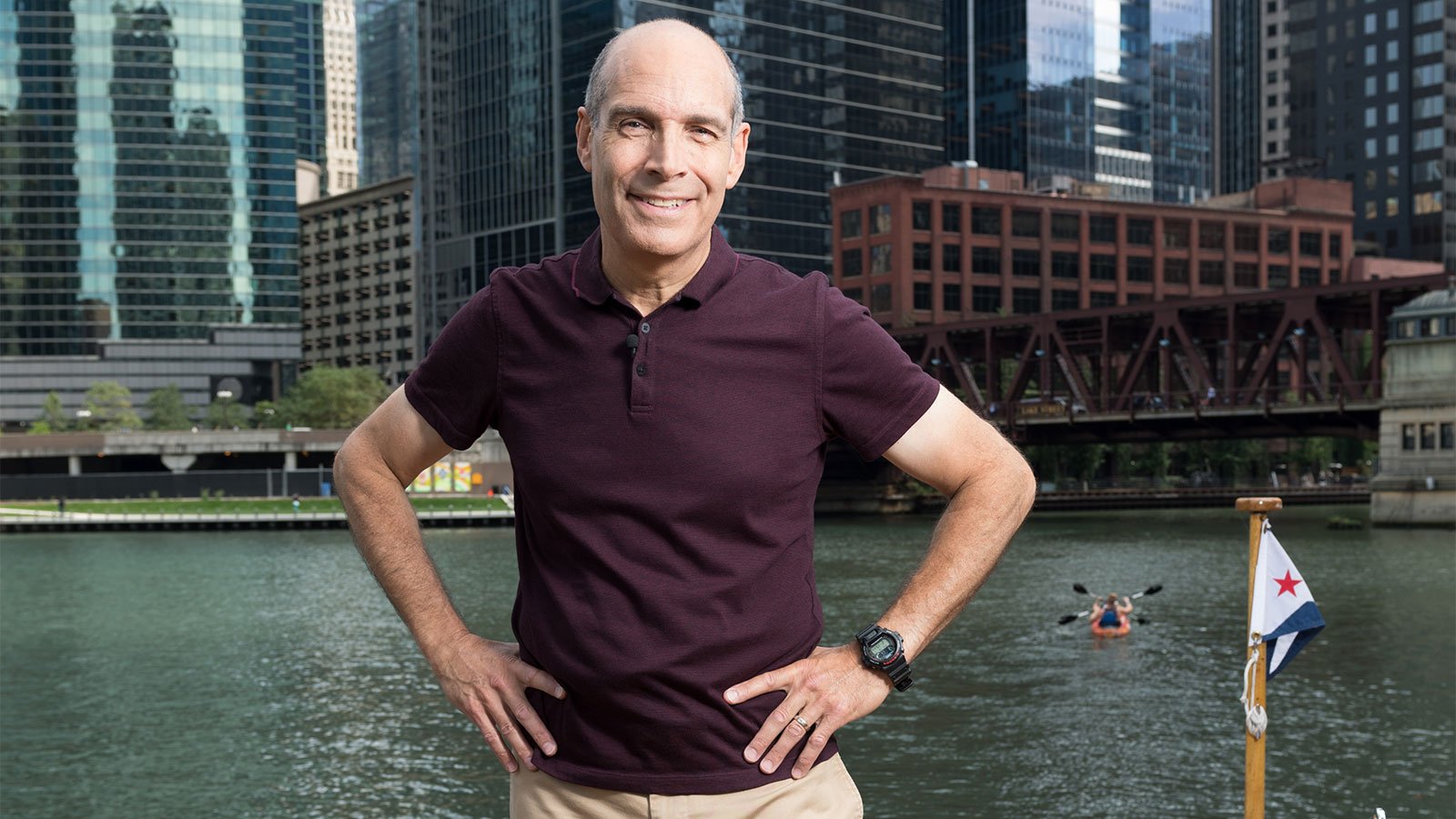

The History of the Chicago River | The Chicago River Tour with Geoffrey Baer

The History of the Chicago River

For centuries, the Chicago River has drawn intrepid explorers, immigrant laborers, and industrial giants to its shores, lured by the promise of its opportunities.

Yet as much as the river has been Chicago’s raison d’être, it has also been our most precarious problem to solve. Chicago has persevered both because of and in spite of its river and only through great feats of ingenuity, hard work, and sheer will. We have deepened and dredged the river, widened it, and even reversed its flow.

This is the story of the Chicago River. It is at turns hapless and hopeful and, like Chicago itself, it is always evolving, and never dull.

Part One: The New Frontier

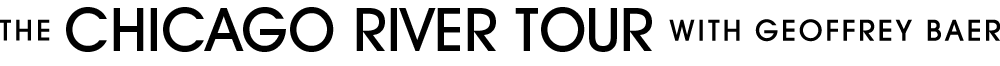

Marquette and Jolliet were on a mapping expedition exploring the Mississippi River, when local Miami people showed them a shortcut to the Great Lakes, which became known as the Chicago Portage. Courtesy of WikiCommons

Native American peoples traversed Chicago’s waterways for hundreds of years before the arrival of the first Europeans. Among them were Woodland, Archaic, and Upper Mississippian peoples and later the Miami and Potawatomi.

Back then, the area teemed with beaver, black bear, fox, and deer.

The Algonquian people called the slow and meandering river that led to the Great Lakes Checagou in reference to the pungent wild leek that grew along its bank.

In 1673, a French missionary and a French-Canadian explorer — Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet — were returning to Canada after a mapping expedition that had brought them along the Mississippi River into present-day Arkansas and Mississippi. They paddled upstream in their birchbark canoes, headed for the Fox River and Green Bay, until some local Miami people tipped them off to a valuable shortcut. If they headed instead for the Illinois and Des Plaines Rivers, they would come to a portage where they could carry their canoes across a few miles of swampy marshland and arrive at the Great Lakes in a fraction of the time.

Marquette and Jolliet paddled to what is now the suburban town of Lyons, slogged across the muddy portage to the Chicago River, put their boats back in the water, and continued on to Green Bay.

Jolliet immediately recognized the significance of the portage. The shortcut could accelerate travel and trade between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River, the two major transportation networks of the North American continent.

A city built at the mouth of that canal would be poised for greatness.

“We could easily sail a ship to Florida,” he wrote in his journal. “All that needs to be done is to dig a canal through but half a league of prairie from the lower end of Lake Michigan to the River of St. Louis [today’s Illinois River].”

Word of the “Chicago Portage” spread quickly, and it soon became a popular route for French and British fur traders and missionaries.

The First Settlers

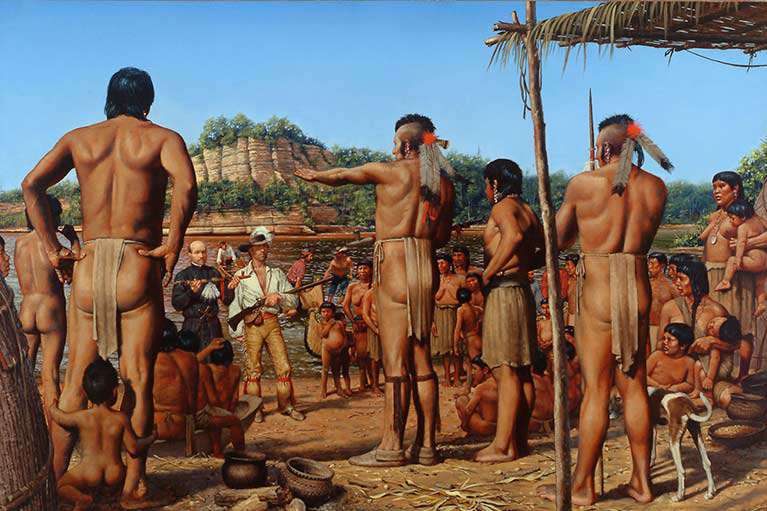

A bust of Jean Baptiste Point DuSable today stands on the north bank of the Chicago River, near Michigan Avenue, where his home once stood. Photo by Jessica Pupovac

Sometime in the late 1770s, Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, a black man of French and African descent, and his wife, a Potawatomi woman named Kittahawa, became the first known settlers to build a permanent home and raise a family on the banks of the Chicago River.

Leveraging Kittahawa’s kin networks, they opened what became a highly successful trading post along the northern bank of the river near the lakefront, where the Michigan Avenue Bridge stands today. In time, a small community built up around them. By the time DuSable sold his property in 1800, the DuSables had amassed a large estate — and Chicago had earned national attention as a strategic location in the growing economy of the new American frontier.

Fort Dearborn and The First Channels

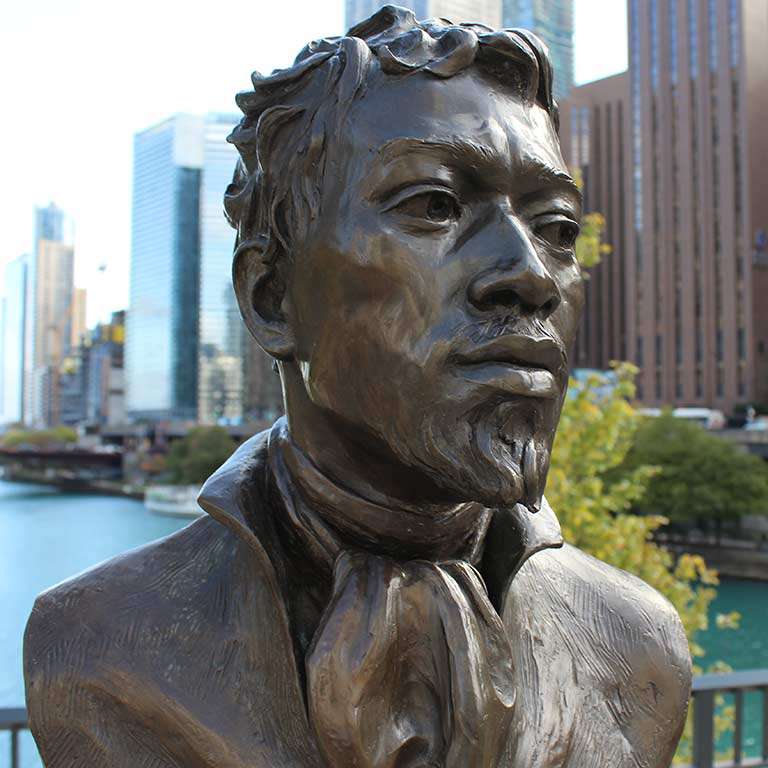

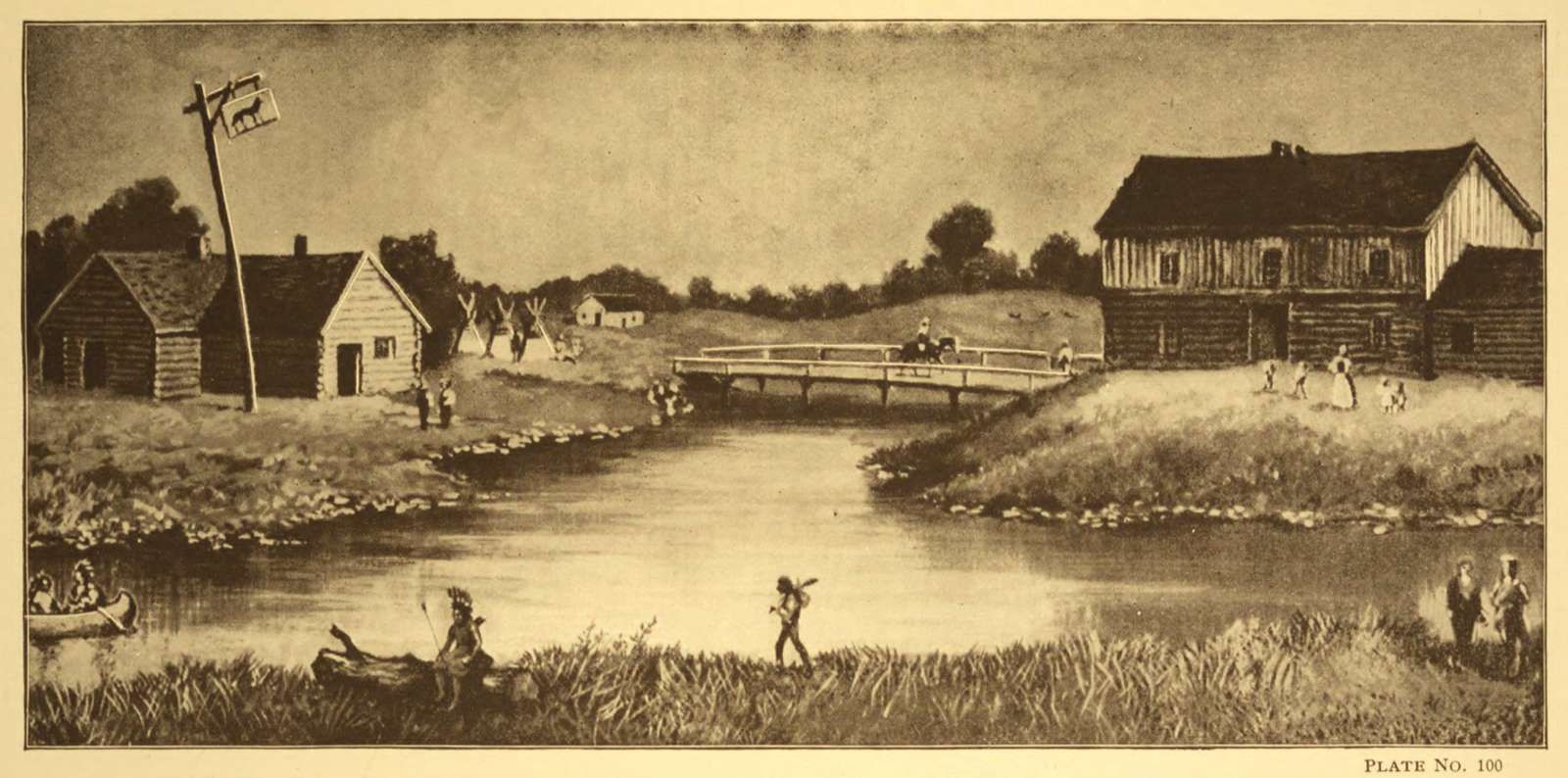

The Kinzie Mansion, which John Kinzie purchased from Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, and Fort Dearborn, painted circa 1900 by an unidentified artist. Oil on canvas. Photo credit: Chicago History Museum

In 1795, as part of the Treaty of Greenville, a confederation of Native American tribes granted the United States rights to a six-mile parcel of land at the mouth of the Chicago River.

Soon after, in 1803, the U.S. military built — and after a devastating battle with the Potawatomi, rebuilt an outpost. Fort Dearborn was erected across the river from the old DuSable estate to guard the Chicago Portage and formally claim the territory for the young United States of America.

At that time, the Chicago River turned south at what is now Michigan Avenue, forcing sailors to navigate around a sandbar the shape of an elephant’s trunk to get in and out of the harbor. It made travel particularly difficult for large vessels, which would drop anchor outside of the harbor and send their goods to shore on smaller ships.

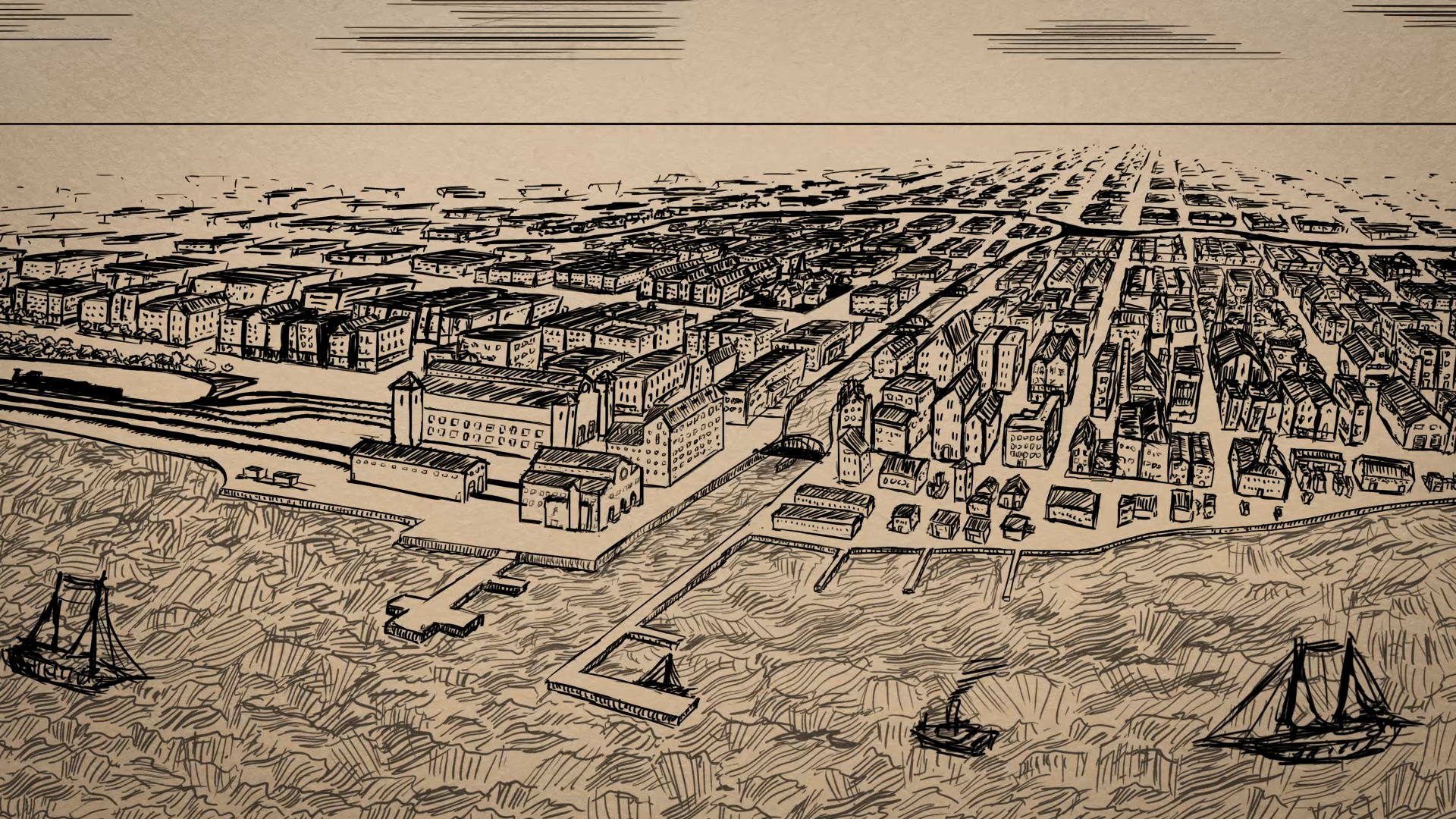

A map of Chicago in 1812, from History of Chicago by A.T. Andreas. Photo credit: Chicago History Museum

Several times between 1816 and 1828, in what is the first recorded attempt to engineer the river, soldiers dug channels through the sandbar. But their attempts proved futile. The wind and waves of Lake Michigan were stronger than their ditches, and their channels repeatedly filled in with sand.

In 1833, Congress appropriated funds to improve the harbor and construct piers to fortify the channel. The investment opened the river for larger ships and increased Chicago’s standing as a center for cross-continental trade.

Wolf Point

Photo courtesy of University of Illinois

Mark Beaubien, owner of the Sauganash Hotel. Photo credit: Chicago History Museum

By the 1830s, Chicago had become a raucous frontier village with a mix of French Canadians, Yankees and Native Americans. The social center of that village was Wolf Point. Located at the junction of the Main Stem and the North and South Branches, Wolf Point provided the perfect stopping place for explorers and traders en route to and from the Chicago Portage.

The taverns that stood on each of the three points were the epicenter of social and economic activity in the young town of Chicago, and the spot where locals held dances, public debates, and in the winter, hatched plans for impromptu horse races across the frozen river.

Mark Beaubien was the owner of one of the most famous of those taverns. He arrived in Chicago from Detroit in 1826 with his wife, Monique, and their five children. He would ultimately father 23 children by two wives.

Feature: The View From Wolf Point, Chicago’s Birthplace

Travel with Geoffrey Baer to the modern river junction that was the first economic and social hub of Chicago, back when it was just a little-known frontier town.

Beaubien opened his hotel in 1831 near the corner of today’s Lake Street and Wacker Drive. He named it the Sauganash Hotel, in honor of his friend Billy Caldwell, who was half-Native American and half-Irish and whose Indian name was Sauganash.

Beaubien cracked open casks of whiskey, played his fiddle, and regaled guests with stories late into the night. When the city was incorporated in 1833, the first elections and many of Chicago’s first town meetings took place at the Sauganash.

Beaubien sold the hotel in 1834, and it operated under various owners and names until the building was destroyed by fire in 1851.

Part Two: An Industrial Boomtown

View east of Rush Street Bridge, toward the mouth of the Chicago River, heavily congested with ship traffic. The footing of the Rush Street Bridge is visible in the foreground. At left, the McCormick Reaper Works can be seen, and on the left, one of the Sturges and Buckingham elevators is visible. Note on back reads: “A reproduction of a photograph taken before fire of 1871. Photo courtesy Chicago History Museum

It took only a few decades for Chicago to completely transform from a small, rowdy, frontier settlement to a bustling, industrial boomtown full of builders, hustlers, and businessmen.

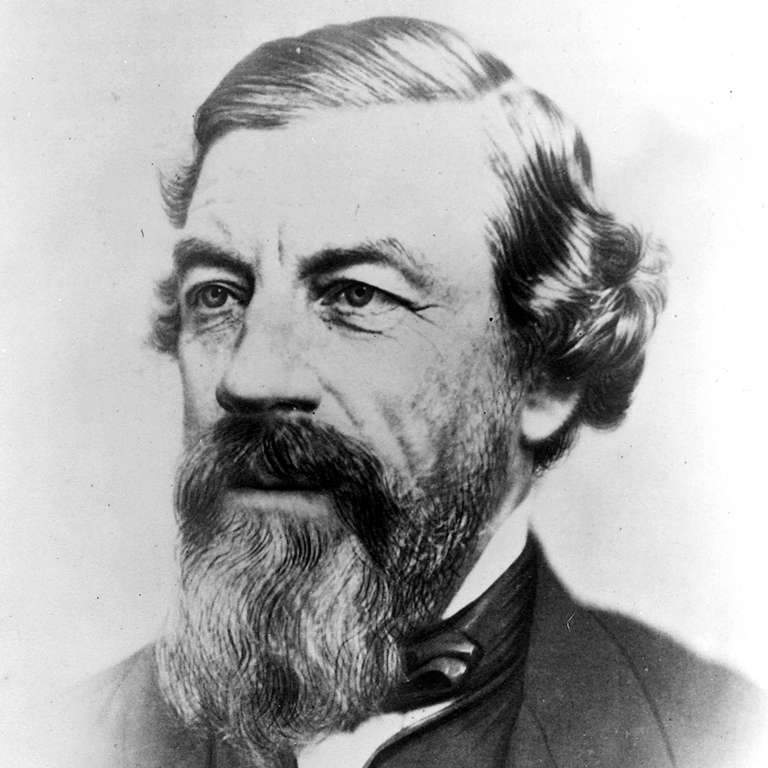

One of the few people to witness that transformation in its entirety was Gurdon S. Hubbard. He grew up in Vermont and Montreal and first arrived in Chicago in 1818 as a young employee of a fur trading company. He later recounted his first glimpse of the place that would become his home:

“The waving grass, intermingled with a rich profusion of wild flowers, was the most beautiful sight I had ever gazed upon. In the distance the grove of Blue Island loomed up, beyond it the timber on the Des Plaines River, while to give animation to the scene, a herd of wild deer appeared, and a pair of red foxes emerged from the grass within gunshot of me...I was spell-bound and amazed at the beautiful scene before me.”

A week later, as his fellow voyagers traversed the Chicago Portage headed for the Mississippi River, he described the “fatigue and hardship” of the crossing through what became known as Mud Lake:

Chicago in 1820 Photo courtesy MWRD

"This lake was well named; it was but a scum of liquid mud, a foot or more deep, over which our boats were slid, not floated over, men wading each side without firm footing, but often sinking deep into this filthy mire, filled with bloodsuckers, which attached themselves in quantities to their legs. Three days were consumed in passing through this sinkhole of only one or two miles in length."

Hubbard later moved from Canada to Danville, Illinois, where he became a member of the Illinois General Assembly and argued for the construction of a canal that could ease the journey across the portage.

The project required a tireless advocate like Hubbard. The task was enormous, and the role of the federal government in funding such a massive public works project in the early nineteenth century was highly controversial. If the young state of Illinois wanted it done, they would have to do it themselves.

Gurdon Hubbard landed in Chicago as a young fur trader. He went on to build Chicago's first stockyard and help Chicago become a great metropolis before his death in 1886. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

Hubbard eventually won the support of the General Assembly, and in 1834, he and his wife moved to Chicago. They built a three-story, brick warehouse on the south bank of the Chicago River, near modern-day LaSalle Street. There, they opened the city’s first meat-packing business, using ice cut from the river during the long, cold winter to cool their meat into the summer. Hubbard also became one of Chicago’s first village trustees.

Meanwhile, with the state in economic crisis, planning for and funding of the canal happened in fits and starts. For a while, due to the complications of digging through the limestone between the Des Plaines and Chicago Rivers, a plan to connect the Des Plaines to the Calumet River instead of the Chicago gained supporters. But as Libby Hill reports in her book, The Chicago River: A Natural and Unnatural History, Hubbard lobbied to preserve the original route, arguing that wherever the canal’s route joined with Lake Michigan, a great city would rise. And if the state of Illinois was footing the bill, shouldn't they also be reaping the benefits, rather than sharing them with Indiana, a stone’s throw from the mouth of the Calumet?

Chicago Population, 1840–1900

|

4,470 |

|

|

29,963 |

|

|

112,172 |

|

|

298,977 |

|

|

503,185 |

|

|

1,099,850 |

|

|

1,698,575 |

|

| Source: U.S. Census |

When the groundbreaking ceremony took place on July 4, 1836 on the banks of what is now the Bridgeport neighborhood, Hubbard wielded a spade and delivered the closing address, sharing stories of crossing the Chicago Portage as a teen.

Meanwhile, the boom was on in Chicago. The flood of canal workers and land speculators transformed Chicago from the town of “four and a half houses, a fort and a Potawatomi town” Hubbard described when he first arrived to the fastest-growing city in the world, according to historian Donald Miller.

In 1832, a small lot on Clark Street sold for $100. Two years later, the same property sold for $3,000. And a year after that, it sold for $15,000. A newspaper reporter wrote, “[E]very man who owned a garden patch stood on his head, [and] imagined himself a millionaire….”

It would take 12 years to finish the 96-mile ditch, dug mainly with picks and shovels. Immigrants, many of them from Ireland, earned a dollar and a pint of whiskey day for up to 15 hours of backbreaking work. Their wages were often paid in a nearly worthless kind of promissory note called canal scrip. Many died of malaria and waterborne diseases while channeling through the swampy lowlands. Still others were killed or maimed in work-related accidents.

Photo courtesy Chicago History Museum

Bridgeport, then a riverside shantytown known as “Hardscrabble.” It became one of Chicago’s many “river wards,” populated mainly by immigrant laborers on the lowest rungs of Chicago’s socioeconomic ladder. Cholera epidemics in the late 1840s and early 1850s took a particularly fierce toll on these communities.

They also suffered intense anti-immigrant sentiment. The editors of the Chicago Tribune, blamed them for the cholera outbreaks that ravaged their communities:

“A large majority of the deaths are confined to the foreign population passing through or permanently stopping here. And when their habits of living are considered — how they dissipate with poisonous liquors and slops, and eat every manner of green and decaying vegetables, in quantities that no native could stand without injury — the wonder is, not how so many die but how they live.”

But outside the river wards, there were fortunes to be made. The Illinois & Michigan (I&M) Canal opened in the spring of 1848. But it soon was eclipsed as the fastest way to transport goods or travel through the Midwest. In October that same year, the Galena and Chicago Union Railroad’s inaugural train left Chicago.

The new accelerated transportation options didn’t just transform Chicago; they transformed the nation. Sugar and cotton from the South were reaching the East Coast in a fraction of the time, reducing prices, and increasing demand. Throughout the Midwest, farmers had gained valuable new markets for their wheat, corn, and lumber. And Chicago was the epicenter of it all.

The Chicago River quickly became a jumble of docks, bustling with cargo and passenger ships.

Construction boomed. Between 1853 and 1873, William B. Ogden, Chicago’s first mayor, dug enough clay for bricks along the North Branch of the river that he created a channel. He connected it at both ends to create Goose Island, the only island in the Chicago River.

Chicago’s public works, which soon included expanding the harbor, widening and dredging the river, lifting the city out of the mud, and building a sewer system, provided jobs for a continuing influx of immigrant laborers.

So did the steel mills, lumber yards, and meat, glue, soap, and leather plants which grew up along the river, dumping their industrial waste into its waters.

In 1865, the Union Stockyards opened in Bridgeport. It became the largest slaughterhouse in the world and a short tributary to the river became its giant, fetid ditch, where meatpackers discarded their unwanted carcasses, eyeballs, bones, and rancid oils. The methane gasses that would often rise from the depths to the surface earned it the nickname of Bubbly Creek. Upton Sinclair immortalized it in his 1906 novel, The Jungle:

“Here and there the grease and filth have caked solid, and the creek looks like a bed of lava; chickens walk about on it…and many times an unwary stranger has started to stroll across and vanished temporarily.”

Though Bubbly Creek may have seen the worst of it, the rest of the river wasn’t much better off.

A chicken standing on crusted sewage in Bubbly Creek at West 39th and South Morgan Streets in 1911. Photo courtesy Chicago History Museum

Man standing on crusted sewage in Bubbly Creek at West 39th and South Morgan Streets in the Bridgeport neighborhood, April 19, 1911. Photo courtesy Chicago History Museum

The kaleidoscope of colors and smells emanating from the river became so putrid, it was a running joke among Chicagoans. As Finley Peter Dunne later wrote in his satirical “Farewell to the Chicago River,” published in the Chicago Journal: “Twas the prettiest river f’r to look at that ye’ll iver see (sic)…. Green at th’ sausage facthry, blue at th’ soap facthry, yellow at th’ tannery, ye’d not thrade it f’r annything...”

After Chicago constructed one of the country’s first comprehensive sewer systems, beginning in 1855, an even larger volume of concentrated sewage began mingling with the river’s industrial and animal waste. They all emptied into the lake, the city’s source of fresh drinking water. Outbreaks of dysentery, cholera, and typhoid arose periodically, stoking fears that one day an outbreak of epidemic proportions would destroy the city. One proposal to solve this problem was to reverse the river so it flowed not into the lake but instead drained instead into the I&M Canal, re-directing the city’s sewage down toward the Mississippi. The first attempt at this involved deepening the I&M Canal where it joined the South Branch and installing pumps to help nudge some of the foul water in the desired direction.

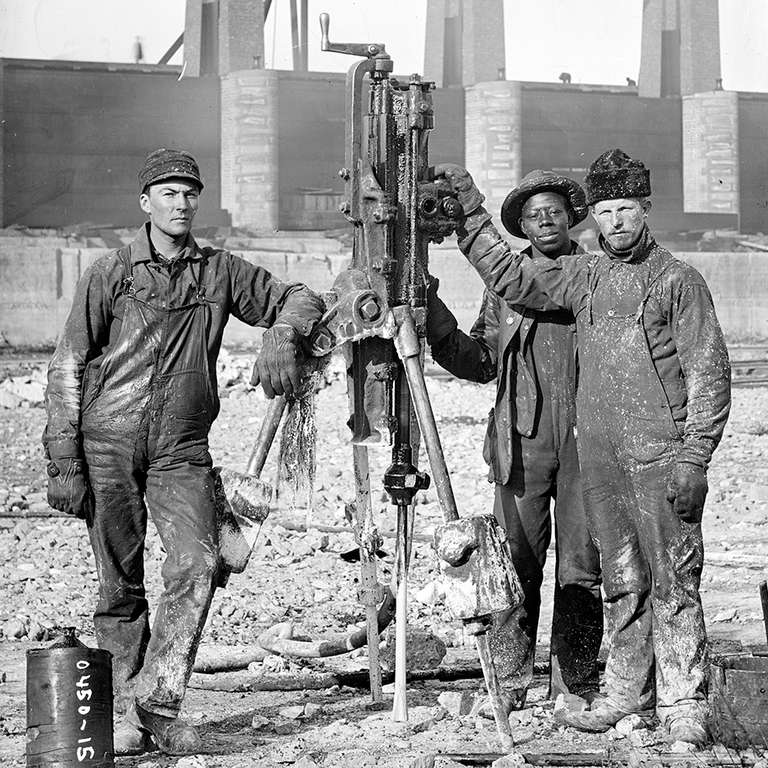

Laborers pose next to a compressed air rock drill during the construction of the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal near Lockport, Illinois in 1896. Photo courtesy MWRD

But the canal simply wasn't deep enough to consistently pull the current away from the lake, particularly during periods of heavy rain. With Chicago’s population continuing to rise, a more drastic and lasting solution was needed.

In 1889, Chicago voted to create the Sanitary District of Chicago (now the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago, or MWRD) and assigned the new agency the task of permanently reversing the direction of the Chicago River by digging an entirely new and bigger canal.

As New York Times reporter Theodore Dreiser wrote of the herculean task at hand in 1895:

“Chicago appears at its best in an enterprise like this…The men who have it in their charges are typical Chicagoans – men of enterprise rather than of education – of action rather than culture. Their faith in their own powers is of the kind that literally moves mountains.”

Feature: How Chicago Reversed Its River — An Animated History

Learn the story of how, more than 100 years ago, Chicagoans pulled off one of the most audacious engineering feats in U.S. history.

Construction of the 28-mile Sanitary and Ship Canal began in 1892 and was completed in 1900. And although the reversal of the Chicago River is one of the greatest American feats of civil engineering, it has been celebrated, and debated, ever since.

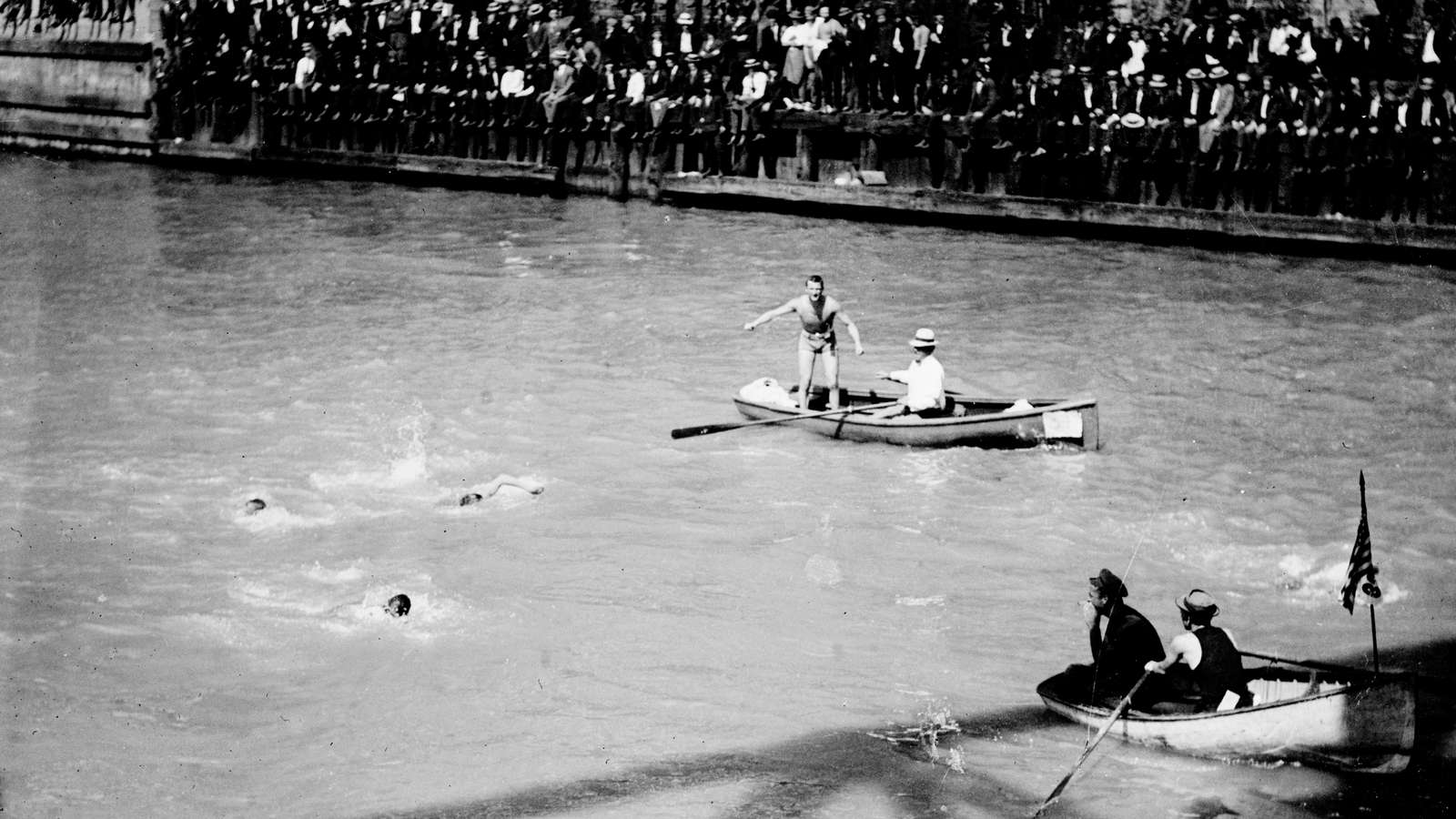

For a short time, Chicagoans were so infatuated with the clean lake water entering the Main Branch that they wanted to jump right in. In 1908, the Illinois Athletic Club organized its first Chicago River Marathon. For more than two decades, it drew thousands of curious spectators to watch swimmers race from the mouth of the river, near Lake Michigan, all the way to Jackson on the South Branch.

Swimmers race down the Main Stem of the Chicago River during a river-swimming marathon in 1909. Photo courtesy MWRD

But the canal didn’t put an end to Chicago’s drinking water challenges. Several growing lakefront communities continued dumping their waste into Lake Michigan.

The Sanitary District’s jurisdiction was expanded, and additional channels and canals were constructed to the north and south of the city to re-direct the flow away from the lake. They included the 8-mile North Shore Channel in 1910 and the 16-mile Cal-Sag Channel in 1922.

Laborers work underground, laying new sewer pipes in 1929. Photo courtesy MWRD

Workers seen inside a cofferdam during bridge construction in 1901. Photo courtesy MWRD

Soon after, the MWRD laid additional pipes so that they could divert wastewater to treatment plants and filter it before it reached the river. Today, there are seven treatment plants scattered throughout what is now referred to as the Chicago Area Waterways.

Meanwhile, neighboring states along the Great Lakes grew concerned about the diversion of what was then 8,500 cubic feet per second of fresh, Lake Michigan water through Chicago and downstream to the Gulf of Mexico. After the Supreme Court ruled against Chicago in 1930, locks and controlling gates were installed to control the diversion.

Part Three: Regeneration

Chicago Fire cyclorama scene of the wholesale district, looking west along the Chicago River in 1871. Photo courtesy MWRD

Much was lost in the Great Chicago Fire: some 250 lives, 17,000 buildings, and thousands of pages of Chicago’s early history. But the monument that stands today on the southeast corner of the bridge that spans the Chicago River at Michigan Avenue is a testament to what came next:

“The Great Chicago Fire in October, eighteen hundred and seventy one, devastated the city. From its ashes the people of Chicago caused a new and greater city to rise, imbued with that indomitable spirit and energy by which they have ever been guided.— Erected by the trustees of the B. F. Ferguson Monument Fund, 1928 signed”

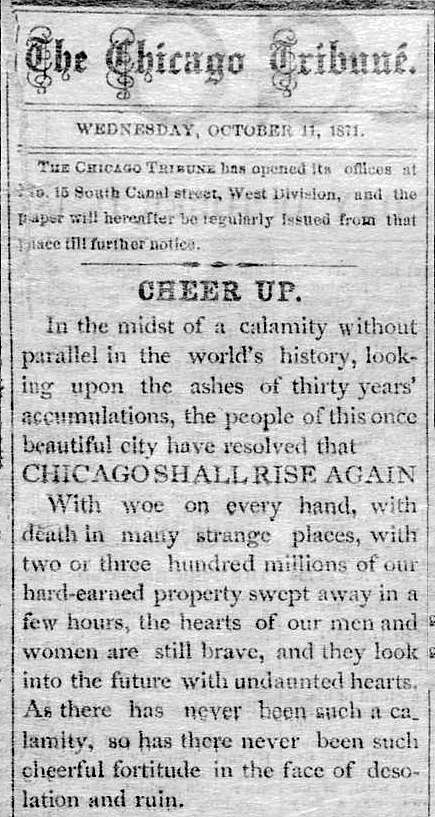

Before the ashes had cooled, Chicago had vowed to rebuild. Three days after the fire, the Chicago Tribune proclaimed, “The people of this once beautiful city have resolved that CHICAGO SHALL RISE AGAIN.”

The determination, energy, and talent summoned to do so transformed the city from an industrial boomtown into a twentieth century metropolis.

William Bross, then part-owner of the Tribune, traveled to New York to seek help for the ravaged city. According to historian Donald Miller, Bross proclaimed, “Go to Chicago now! Young men, hurry there! Old men, send your sons! Women, send your husbands! You will never again have such a chance to make money!”"

The first post-fire buildings didn’t look much different than the ones that burned down. But technology advanced rapidly. Within 20 years, engineers, architects, and inventors converged on Chicago and began designing an entirely new type of city. In the decades that followed, Chicago became the nation’s premiere location for architectural innovation.

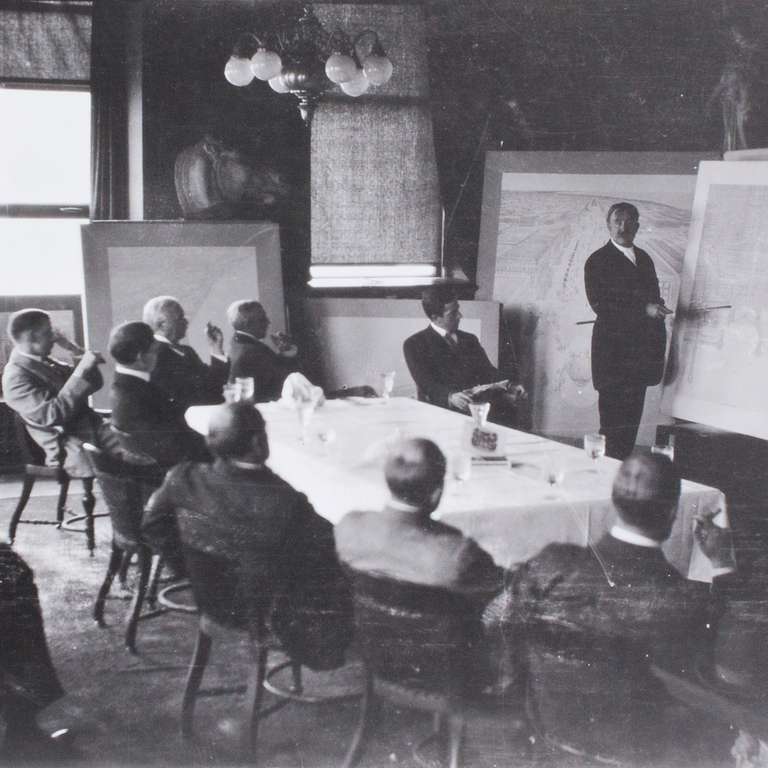

In 1909, city planners Daniel Burnham and Edward H. Bennett reimagined the river as part of their sweeping “Plan of Chicago.” They would alleviate overcrowding of ships in the narrow river by building several lakefront piers. Out of that proposal came Navy Pier, completed in 1916.

A view of Lake Street taken from LaSalle Street in 1872. Photo courtesy Chicago History Museum

Daniel Burnham presenting his plan at his offices in 1908. Courtesy of The Ryerson and Burnham Libraries at School of the Art Institute of Chicago

The grand opening of Wacker Drive in 1926. Photo courtesy Chicago History Museum

Burnham and Bennett also envisioned a magnificent bridge that could join the river’s North and South branches at Michigan Avenue, already Chicago’s main street. The double-decked drawbridge was completed in 1920.

The plan also called for an elegant esplanade lining the river’s Main Stem. The double-decked Wacker Drive was completed in 1926, and its upper level was loaded with neoclassical trimmings, such as balustrades and obelisk-shaped light fixtures.

The Chicago River's Most Deadly Disaster

As Chicago’s downtown riverfront and lakefront were being reimagined and redesigned, tour boats increasingly sailed alongside freighters and other industrial vessels. In 1915, one such vessel tipped over, resulting in one of Chicago’s great tragedies.

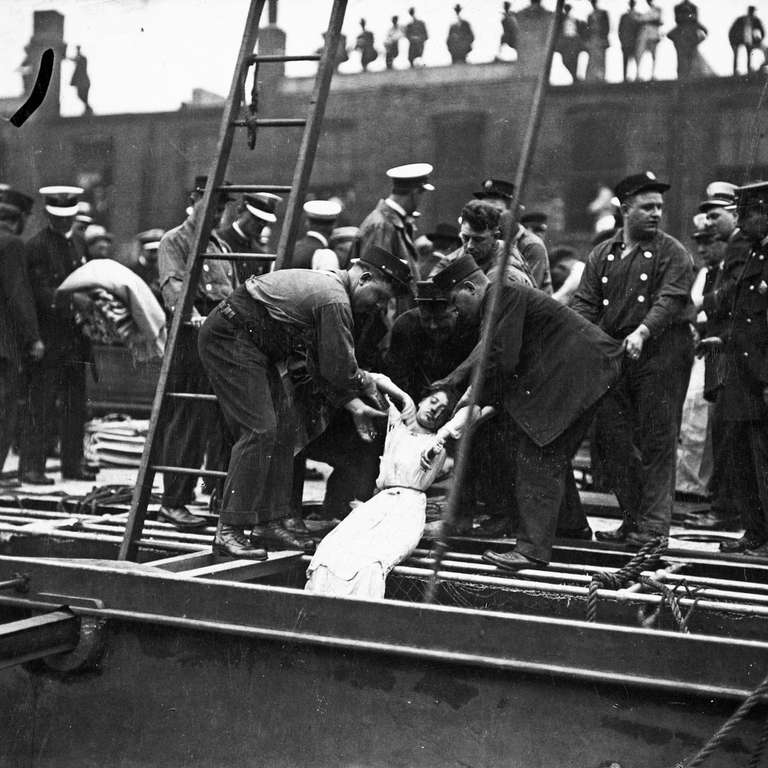

More than 800 people lost their lives on the SS Eastland on July 24, 1915, fewer than 20 feet from shore.

That morning, 2,500 Western Electric employees, many of them young, Czech immigrants, were heading across the lake for a company picnic in Michigan City, Indiana.

Men lifting a lifeless female victim from below deck of the SS Eastland on July 24, 1915. Photo credit: Chicago History Museum

It’s unlikely any of them knew the Eastland’s longtime reputation as an unstable ship. It had been remodeled several times to accommodate more passengers, and a concrete deck had been added above the waterline. Then, in the wake of the Titanic disaster in 1912, several lifeboats were added to the top of the ship, making it even more top heavy.

The huge vessel rolled over on its side in the Chicago River, just moments before the Eastland was scheduled to leave the dock. Some passengers managed to scramble onto the slippery metal hull where they awaited rescue. Several people along the top deck jumped or fell into the filthy river. Some of those who jumped quickly drowned, while others clung to boxes and other floating objects thrown by passersby. Passengers trapped below decks suffered the worst fate. Rescuers cut holes in the ship’s hull and saved a few, but most suffocated or drowned.

River Wards

House boats sitting along the North Branch of the Chicago River, sometime between 1920 and 1929. Photo credit: Chicago History Museum

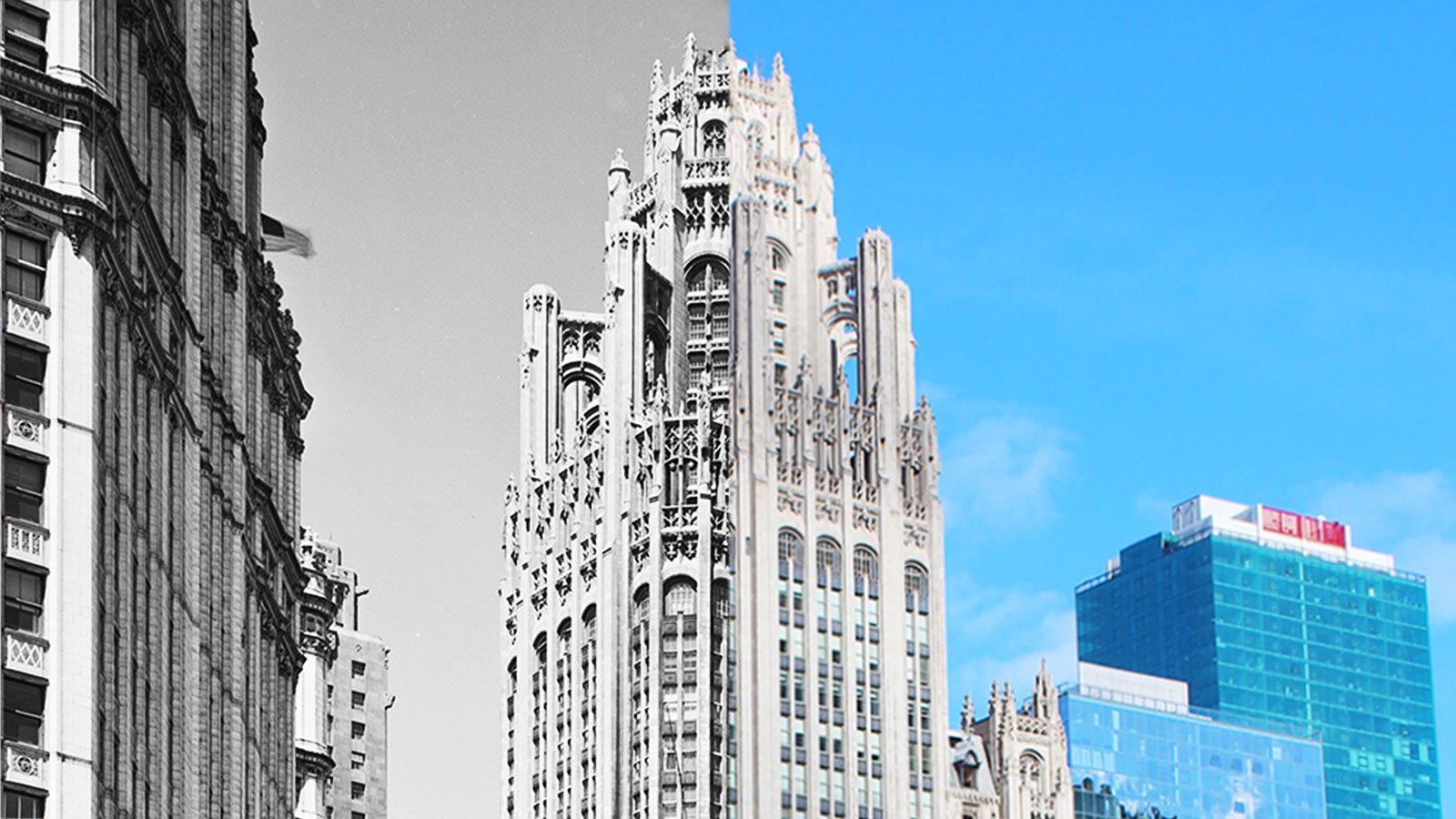

Feature: The Chicago River Then and Now, in Photos

See the ghosts of Chicago’s past in this collection of images taken from various locations along the Chicago River.

Elsewhere along the river, further from the lakefront, the river remained something to be tolerated rather than enjoyed. The opening of Chicago’s first wastewater treatment plant in 1928 reduced the amount of raw sewage, but the river remained laden with industrial chemicals and byproducts. Riverside real estate was cheap, and river wards, dominated by pollution and stench, were still some of the poorest neighborhoods in the city.

During the Great Depression, many people lived directly on the river’s North Branch, in a floating squatters’ camp lined with makeshift houseboats near Irving Park Road.

Around the same time, riverfront property near Division Street was chosen as the site for the one of the nation’s first low-income housing projects, the Chicago Housing Authority’s Julia Lathrop Homes.

The overcrowded, impoverished area on and around Goose Island became known as “Little Hell,” a reference to the conditions on the island as well as the coal-gasification plant that belched out smoke and flames nearby. It was occupied by a succession of immigrant groups who came to work in the steel mills and other factories along the North Branch.

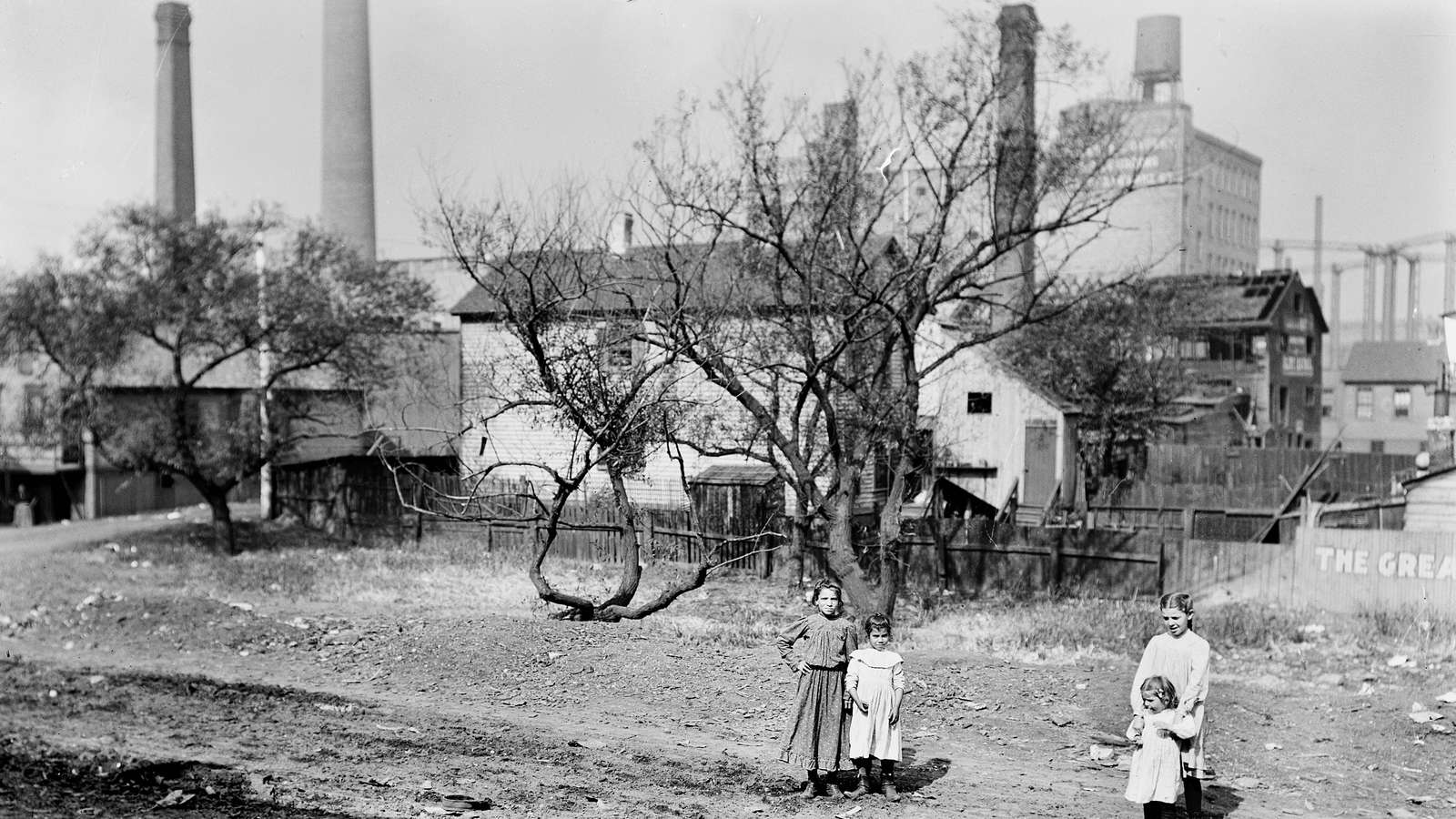

Four girls standing in an empty lot in Little Hell in September 1902. Photo credit: Chicago History Museum

Aerial view of 18th Street and the Chicago River during the river straightening project in May 1929. Photo credit: Chicago History Museum

During World War II, the Chicago Housing Authority bulldozed some of the shanties nearby to build a public housing development called the Frances Cabrini Homes. By the 1960s, it had grown to include high-rise buildings.

Meanwhile, along the South Branch, railroad yards dominated the landscape. As intercity passenger rail gained popularity, the river bank to the south of the Loop became the railroad hub of the Midwest.

A big bend in the river, which previously made it difficult both for trains and river traffic, was straightened in 1929.

Part Four: Rebirth

Kayakers paddle near the Chicago Park District’s Ping Tom Memorial Park on the South Branch of the Chicago River. Photo courtesy of Metropolitan Planning Council

In recent years, the relationship between Chicago’s river and people has entered an entirely new chapter. Aided by the deindustrialization of the mid-twentieth century, a growing sense of environmental stewardship, federal regulations such as the Clean Water Act of 1972, and yet another round of monumental public works projects, the Chicago River continues to undergo dramatic improvements in water quality and accessibility.

Feature: Can We Swim in the River Yet?

The Chicago River is now cleaner than it has been for more than a century, leading some residents to ask when they’ll be able to dive in.

Chicagoans are rediscovering their river, finding new ways to appreciate and improve upon her waters and her shores.

But it hasn’t come easily, and there is still much work to be done. Many of today’s biggest challenges are the unintended consequences of some of the same monumental engineering fixes that saved the city more than a century ago.

The combined storm water and sewage that used to be sent directly to the river is now funneled through water treatment plants before it is released into the river. But population growth and heavy rains continue to overwhelm the system, and rather than immediately back up into area basements, the noxious stew of rainwater, runoff, and human waste is diverted instead into old pipes that flow directly into the river. This is called a combined sewer overflow, or CSO. When it really pours, the locks and gates that were built to slow the flow of Lake Michigan into the river are thrown open, and Chicago’s flooded river releases sewage directly into the lake.

By the late 1960s, these sewer overflows were taking place an average of 100 days per year according to the MWRD, and so state, county, and city leaders devised a system of deep tunnels and storage reservoirs to hold excess storm and sewer water until treatment plants could process it.

The Thornton Composite Reservoir, part of the TARP or Deep Tunnel project, took water for the first time on November 26, 2015. Photo courtesy of MWRD

Construction on the Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP), or Deep Tunnel, began in 1975. The first portion of the massive, underground system began functioning in 1981. It is a project that outdoes even Chicago’s forebearers in terms of investment. When it is completed in 2029 at a cost of $3.8 billion, it should be able to hold up to 20.55 billion gallons of excess water.

The Deep Tunnel project has reduced the number of CSOs that take place in a year. But even in the areas where it is fully operational, it hasn’t managed to eliminate them completely. And given the increasing prevalence of intense, fast-moving storms, the MWRD now says that it will be unlikely that TARP will completely resolve Chicago’s sewage overflow problem in the future.

Volunteers clean up the river near Lathrop Homes in 2004. Courtesy of Friends of the Chicago River

Since shortly after the passage of the federal Clean Water Act of 1972, a network of environmental groups have steadily been gaining in size and political strength and using it to monitor polluters and pressure government agencies, including the MWRD, to continue improvements to the Chicago River.

Foremost among them is Friends of the Chicago River, which also organizes volunteer work days to remove invasive plants and seed the river banks with native, local species. In doing so, they have not only reduced the amount of runoff that flows into the river and storm water that makes it into the sewers, they have also restored dozens of acres of habitat for turtles, fish, and other creatures along the river.

The MWRD has also documented a dramatic increase in the number of species in the river system. From 10 known species in 1974, that number has ballooned to 76 in 2017, including 59 found just since 2000.

Cumulative Number of Fish Species Collected from the Chicago Area Waterway System, 1974–2016

The number of fish species found living in the Chicago River has been increasing in recent decades, thanks in part to upgrades in infrastructure and treatment technologies. Source: MWRD

The improvements in the Chicago River itself have also helped encourage residential and business development along its banks, including another wave of new high rises, many of them paying homage to the river’s curves and color.

It began with the opening of Marina Towers along the river’s Main Branch in the late 1960s. That building was commissioned by the Janitor’s Union, in part to stop the exodus to the post-war suburbs and preserve their city jobs.

Other industrial areas on the North and South Branches have since undergone their own transformations, some of them still in the making.

In the 1970s, the area formerly dubbed “Smokey Hollow” because of the thick smoke that rose from its factories and forges, often blocking the sunlight, became a destination for artists looking for inexpensive lofts. It has since been rebranded as River North, Chicago's most well-established gallery district. Today, it is full of high-end art dealers, designer furniture showrooms, popular restaurants, and nightclubs.

More recently, warehouses in the old Bridgeport neighborhood, once home to immigrant canal diggers and stockyards, have been transformed into art centers. And in 2016, the Chicago Park District opened a $8.8 million boathouse designed by Jeanne Gang, one of Chicago’s leading contemporary architects, along Bubbly Creek.

The last steel mill on the North Branch, Finkl Steel finally closed in 2014 and is now one of several sites on the North Branch, along with Goose Island and the Chicago Tribune’s printing plant, that developers are eyeing for office, commercial, and even residential development. Proposals for all of these sites include parks and riverwalks that would take full advantage of their riverside locations, now considered an asset.

An artist’s rendering of Riverline, a mixed-use development now under construction along the south branch of the Chicago River. Photo courtesy Perkins+Will

For many low-income residents, this has meant a new shortage of affordable riverside housing. Cabrini-Green was demolished in 1995 and is now the site of a mixed-income development surrounded by high-end retail. Lathrop Homes, similarly situated, is now being redeveloped into a mixed-income development that will have significantly fewer public housing units than it did when first constructed.

New city guidelines aim to protect public areas along the riverfront for all Chicagoans to enjoy. Beginning in 1999, all new residential and business development along the river is required to create or preserve at least 30 feet of public space along the river’s edge.

The Chicago Park District, meanwhile, is facilitating that access and has plans to develop several additional acres of trails along the riverfront, with the goal of having uninterrupted river-edge parks and paths along many of the Chicago River’s formerly industrial banks.

A rowing team practices in the North Branch of the Chicago River near the Chicago Park District’s new boathouse at Clark Park in August 2017. Photo by Ken Carl

Two men fish while one of their daughters plays nearby at the Chicago Park District’s Clark Park on the North Branch in October 2017. Photo by Kristan Lieb

One of the first major riverfront parks to be constructed was Ping Tom Memorial Park in Chicago’s Chinatown neighborhood. It opened in 1999 on the site of a former railroad yard and gave a community that long suffered from a dearth of green space a place to walk, jog, bike, and even launch a boat.

People sit along the River Theater portion of the Chicago Riverwalk in June 2016. Courtesy of John W. Iwanski/Flikr

Feature: Riverwalk Audio Tour

Explore the 10 most iconic buildings along the Chicago Riverwalk, with Geoffrey Baer as your guide.

Meanwhile, the Chicago Riverwalk, completed in 2016 along the river’s Main Stem in the heart of downtown, allows people to stroll at river level from Wolf Point all the way to the lakefront. Just before reaching the lake, a pedestrian underpass bears a 170-foot-long ceramic mural by Chicago-born artist Ellen Lanyon celebrating the rise of Chicago and the river’s significance to the city, beginning with the explorations of Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet in 1673.

Today, on a sunny summer day, local families and tourists vie for space in kayaks, yachts, and rented pontoons on the river’s Main Branch, while along the shore, fishermen cast their lines, and groups of friends sip wine, sitting close enough to dip their toes in the water. Further from downtown, great blue herons, muskrats, and river otters leap in and out of the river. Chicagoans are appreciating both what their waterways have meant to the city historically and what they can mean in the future.