When a messenger woke Mayor Roswell B. Mason in the early hours of October 9, 1871, the fire that ravaged his city of 300,000 people illuminated the faults that had been smoldering for decades.

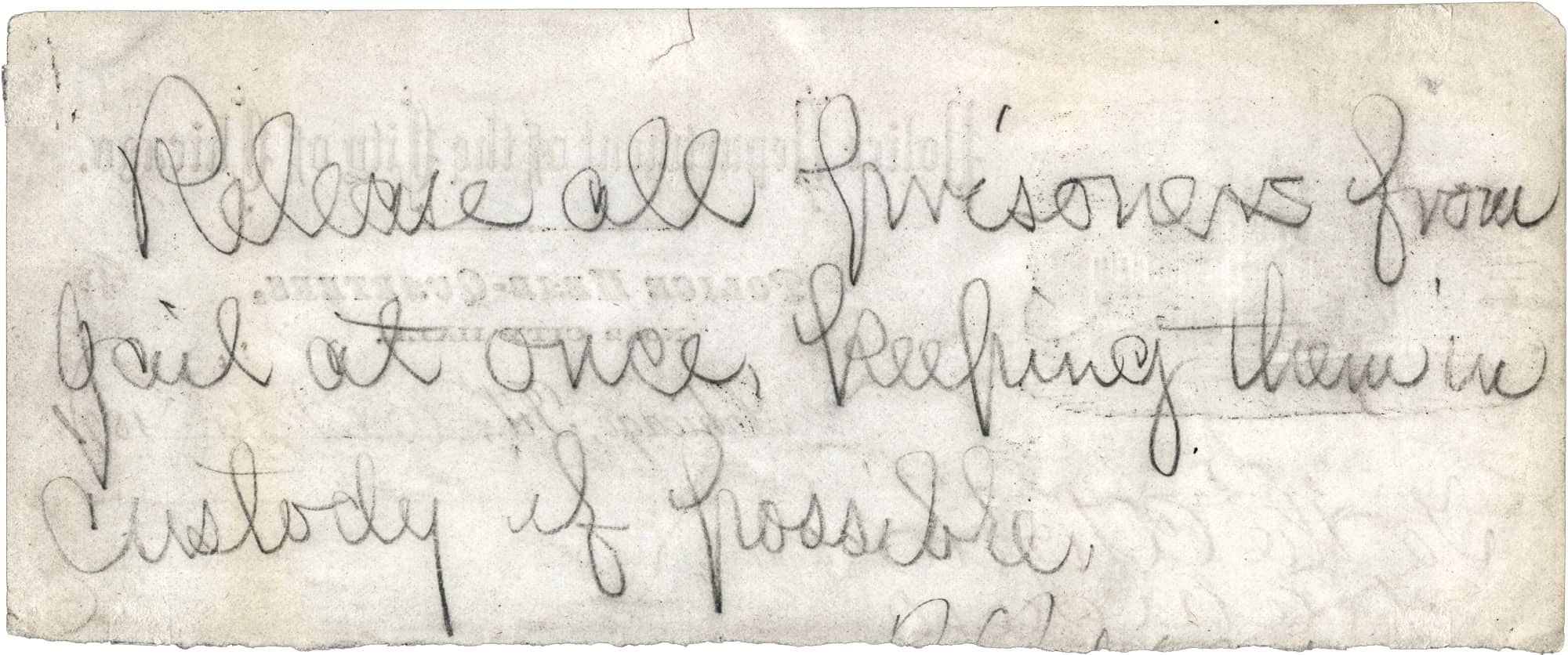

The mayor sprang into action. According to a descendant of Mason, Caroline Thompson, the mayor rode his horse from his home south of the present-day Loop to downtown to send for help, sending a telegraph to Milwaukee and Detroit in search of aid. He ordered the release of prisoners from the courthouse jail as the building caught fire and smoke filled the cells. He authorized buildings in the path of the fire to be blown up to prevent the spread – an effort that was often fruitless.

But the city that Mason tried to save that night was a tinderbox, in part because of poor structural, political, and institutional planning.

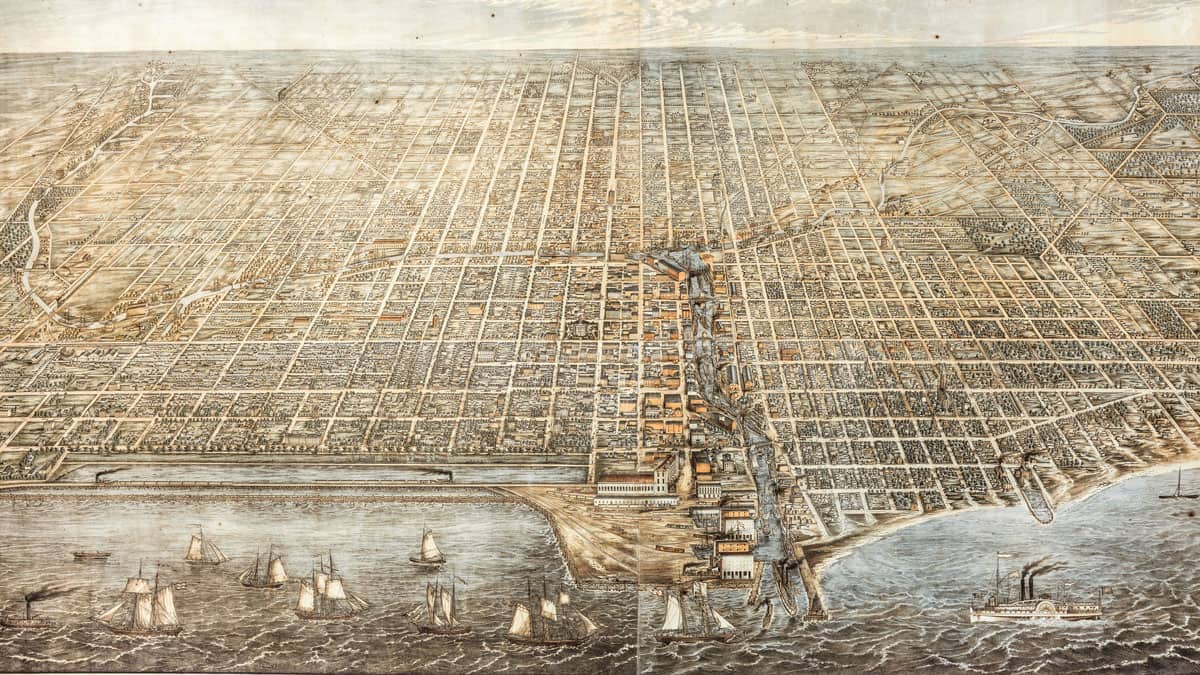

As Dominic Pacyga told WTTW, Chicago’s first flaw was simply its location.

“The city is built without any concern for nature, without any concern for the realities of the prairie. Prairies burn,” he said.

But the city itself was flammable, too. Carl S. Smith, professor emeritus of English at Northwestern University and author of Chicago's Great Fire: The Destruction and Resurrection of an Iconic American City, said there factors – both long-term and short-term – that created the perfect storm for the devastation that followed. Among the long-term factors was the very stuff that the city was made of.

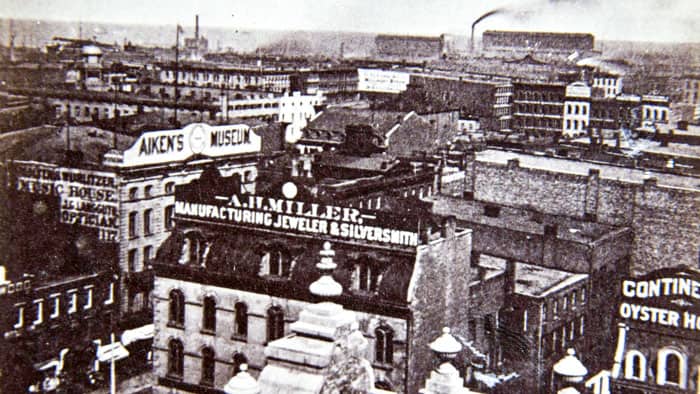

“The city was built in a tremendous hurry, almost entirely out of wood,” said Smith, who is also the curator and author of the Chicago History Museum’s exhibition on the Chicago Fire. “Even stone and masonry buildings had a good deal of wood in them.”

Gallery: Chicago's Wooden Buildings

There were political and economic factors at play that allowed the city to be built so quickly. For starters, there were minimal fire codes, said Smith. Instead there were fire limits – zones in the city where buildings could not be made of flammable materials such as wood. But those limits really only covered the downtown and some adjoining areas, leaving the rest of the city vulnerable.

“The larger problem was that they weren't enforced in any particular way. And so what limited value they had was undercut,” said Smith. Additionally, there were exceptions – such as allowing wooden buildings to be physically moved into the fire limits – that also rendered the codes useless.

Many of the buildings downtown were built haphazardly, giving the city a rickety appearance of densely packed slums and crowded pine buildings. Smith said these buildings were profitable for the owners who rented them out. Adding further restrictions to these buildings – such as using more expensive, less flammable materials – would have meant more money out of the owners’ pockets in the form of higher taxes. And since many landowners held a great deal of wealth in the city, that translated to political power.

City entities warned that the landowners’ buildings were a disaster waiting to happen. According to Donald Miller’s book, City of the Century, the fire department said even Chicago’s nicer downtown buildings were cheaply and dangerously built by “swindling contractors.” These buildings and the wooden sidewalks that lined the streets were “put up in brazen defiance of Chicago’s fire ordinances.” The fire department called for the creation of a building inspection department, more fire hydrants, more firemen, and other measures to prevent a fire. But the local government ignored the recommendations, fearing that increased taxes and more stringent fire codes would dampen economic growth in the rapidly expanding city.

Smith writes in his book that Mason’s immediate predecessor, Mayor John B. Rice, prioritized business growth over safety, warning Chicago’s aldermen that if they wanted safety, it would come at a cost. Rice also claimed that the fire department was well equipped, but officials from the fire department disagreed. And after Mason was elected in 1869, he, too, “hemmed and hawed at the adequacy” of the fire department and also “dodged the question of whether Chicago needed it to be larger and better equipped.”

While these long-term factors allowed Chicago to become a tinderbox, Smith also pointed to more immediate circumstances that exacerbated the city’s lack of preparedness.

“There was a major fire the night before the Great Chicago Fire, which damaged the already-undersized fire department's equipment and put a number of the relatively small number of firemen out of commission. A number of them were just too weak or too injured to work,” Smith said.

In that fire, four blocks were destroyed in a 17-hour blaze at a lumber mill. The fire department was spent. And even though the city had what Smith said was a state-of-the-art alarm system for the time, the delay in responding to the fire proved catastrophic for a city that had seen only an inch of rain since July. And so the tinderbox caught fire, and strong winds that night easily carried the flames through the densely packed buildings, leaving only some stone facades in its wake.

As Smith writes in his book, “In the first twenty-two months of his two-year term, [Mason] had been a low-key administrator who did not try to stretch the limited powers of his office.” However, in the days and weeks that followed the fire, Mason worked to restore order to a city that had been upended by the flames.

As a member of the Citizens Party, Mason was a break from the corrupt brand of politics that was emerging in Chicago. According to Thompson, Mason’s descendant, “Mason was well liked by both his constituents and the press. He was generally thought of as a moral and dedicated family man.”

But Mason wasn’t interested in a second term. Immediately after the blaze, he was consumed by the relief efforts. He imposed martial law, banned smoking, fixed the price of bread, and issued orders that prohibited businesses from increasing prices and profiting from the fire, according to the Chicago History Museum.

As Mayor Mason and other local leaders worked to get aid for the devastated city, Chicagoans began to rebuild. But it would take some time for Chicago leaders and business owners to learn their lesson about fireproofing and constructing safe buildings.