On the morning of April 13, 1992 as commuters were heading to their offices in Chicago’s Loop, fish were swimming in the basement of the Merchandise Mart. A strange flood was rising. But at street level, no one could actually see the flood. What began as a leak in a unique but mostly forgotten underground freight tunnel system became a two-week combination of comedy-of-errors and soap opera that cost almost $2 billion. Building basements were submerged, and life for some was temporarily disrupted. People and institutions were blamed, and unlikely heroes were made. In the end, the Loop dried out, but the flood was an important reminder that forgotten things – even peculiar old tunnels 40 feet below our commute – are worth paying attention to.

Chicago’s Forgotten Freight Tunnels

There would have been no Loop flood in 1992 if it weren’t for the network of underground freight tunnels – and those freight tunnels technically were not supposed to be there in the first place.

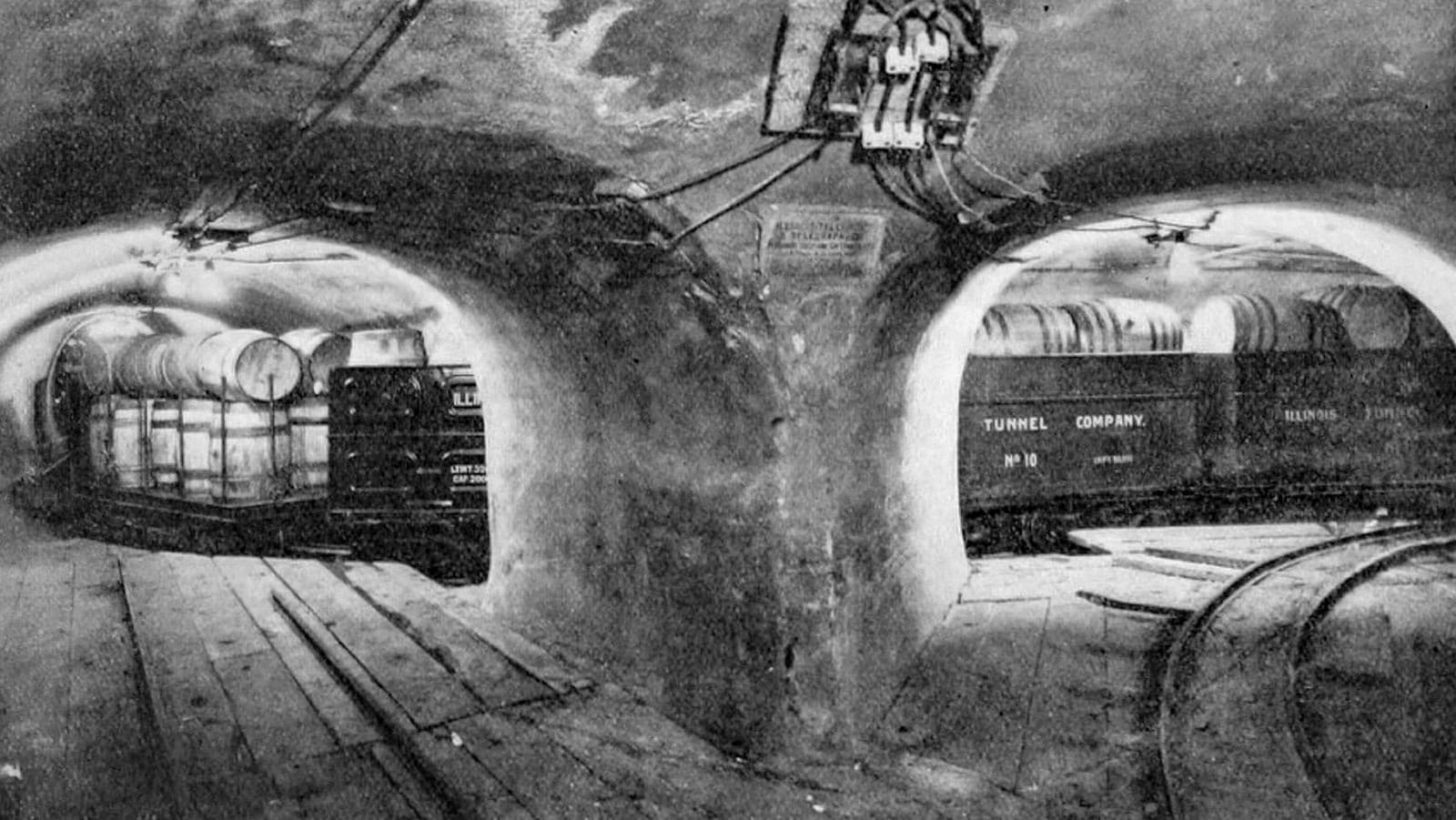

In 1899, the Illinois Telephone and Telegraph Company began construction on the tunnels, digging out clay by hand. The company had received permission to build the tunnels to lay telephone cables, but without informing the city, the tunnels were significantly larger than was needed for telephone cables. The tunnels were large enough for a small electric railroad.

According to transit historian Bruce Moffat, city officials were “shocked” when it came to light what the company was doing in 1902.

“I think the aldermen were more shocked that they were missing out on a revenue-generating opportunity for themselves,” Moffat told Chicago Stories. After some back-and-forth with the city, the Illinois Telephone and Telegraph Company was allowed to continue and was eventually renamed the Chicago Tunnel Company.

The purpose of the freight tunnels was to move such things as coal, water, packages, merchandise, and other items between the buildings that were connected to them. This helped avoid bad traffic congestion in the Loop, which lacked street lights and coherent traffic patterns at the time. A two-foot-wide rail track and small locomotives were also part of the underground activity.

When they were completed in 1914, the tunnels were six-and-a-half-feet wide and as high as eight feet tall in some places. There were 60 miles of tunnels that mostly follow Chicago’s street grid, extending from Superior Street south to 16th Street. In some places, the tunnels run as far west as Halsted Street and as far east as the Field Museum.

“Chicago is the only city in the world that did this,” Moffat said of the freight tunnel system. “It was considered an engineering marvel.”

By 1959, the tunnels had become obsolete as technology advanced and the operation was no longer profitable. It fell to the City of Chicago to maintain the tunnels. Aside from the occasional group of urban explorers touring the tunnels and occasional maintenance, the system was mostly out of sight, out of mind.

“Even though you have abandoned infrastructure, it’s still there,” Moffat said. “It still has maintenance needs. And if you’re not going to do it, sooner or later, something’s going to happen.”

In the early hours of April 13, 1992, something happened.

“There’s Fish in This Water!”

On that cool April morning, many Chicagoans were commuting to their offices downtown. But soon, they would be told to turn around and go back home.

Larry Langford, who at the time was the overnight reporter for WMAQ Radio, told Chicago Stories that in the early hours, he had started to hear some chatter on the scanners that he monitored about water in the basement of several downtown buildings.

“People were having a discussion about the water coming in the basement [of the Merchandise Mart], and one guy says, ‘Hey man, there’s fish in this water!’” Langford said. “Fish in the water? That's no city of Chicago water main leak. We’ve got a big story here.”

(2) Crews worked to clean up buildings on Randolph Street. Image: Chicago Image: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-174350; Chicago Transit Authority, photographer

As the water flooded into the basements of several buildings in the Loop, utilities such as electricity, gas, and plumbing were shut off. Some subway service was disrupted when power was shut down. Trading at the Chicago Board of Trade and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange halted as water poured into their basements. City Hall and the Art Institute reported flooding in their basements, too. Mary Dixon, who was a reporter for WXRT Radio at the time, told Chicago Stories that it was an “odd disaster” because no one could actually see the flood. It also had not rained recently. People were confused as first responders evacuated much of downtown.

“People were just very calm. Some people were kind of laughing,” Dixon said. “It was a reverse commute. They had just gotten in and put down their bags.”

Moffat, whose office was in the Merchandise Mart, described going down to the building’s sub-basement and seeing 25 feet of water.

“You wonder, boy, oh, boy, this is going to take a while to fix this,” he said.

After following the reports from the scanners, Langford went to the river close to the Kinzie Street Bridge.

“What I saw then is a sight that I will never forget as long as I live,” he said. “It looked like the biggest bathtub drain in the world.” That’s when Langford broke the story that the source of the flood was the Chicago River itself. Having been down in the freight tunnels himself, Langford suspected that the river was flooding the tunnels, which were connected to the buildings that were flooding.

Within a few hours, the Loop was mostly deserted except for police cars, fire trucks, and utility trucks.

“On a normal weekday at any given time, you would have thousands of people walking down the street,” Dixon said. “By noon, it was just empty.”

“A Comedy of Errors”

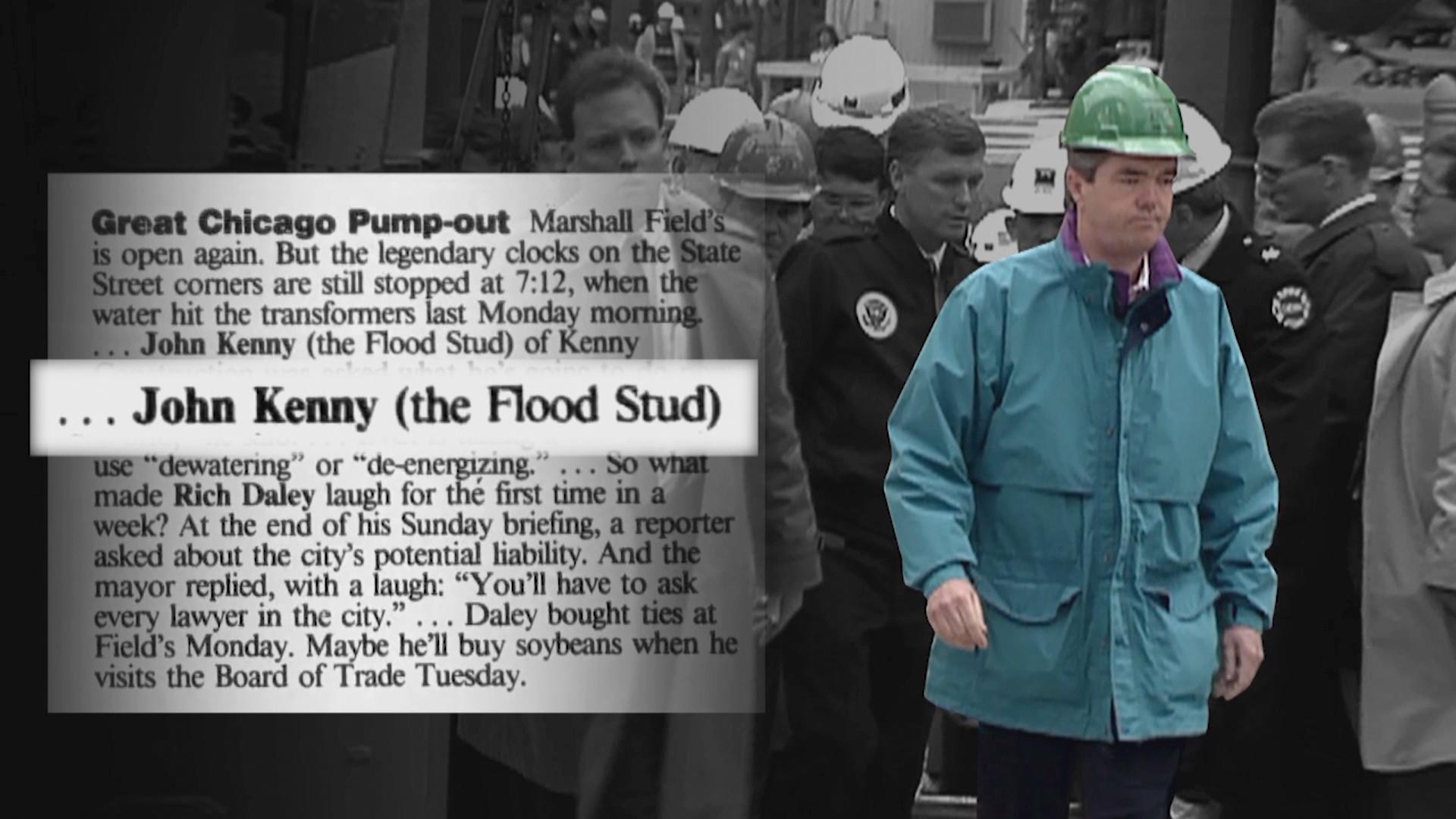

As commuters were leaving the Loop that morning, Mayor Richard M. Daley and officials at City Hall sent in their experts to try to figure out what was going on. Among the experts called in was John Kenny, Jr., of Kenny Construction. His family’s company had worked on several projects for the city, including the CTA, O’Hare runways and roadways, and the Deep Tunnel project.

Kenny, who had heard the reports on the radio about the flooding, told Chicago Stories he didn’t realize the magnitude of the problem until he arrived at City Hall.

“When I walked into City Hall, it was literally total chaos,” Kenny said. Kenny went over to the Kinzie Street Bridge to see how he could help. He directed rocks be loaded into the river near the leak in an attempt to slow it. The locks at the Sanitary and Ship Canal in Lockport were opened to slow the flow of water.

Given Kenny’s history of working on the city’s tunnels, the mayor asked him if he wanted to lead the efforts to solve the problem, and he agreed, but with two caveats.

“I don’t want any red tape on anything. I want to be able to do what I have to do and do it now,” Kenny recalled telling the mayor. “And safety trumps everything.”

During a press conference later that morning, Mayor Daley brought Kenny up to speak. “Whoa, take over the press conference?” Kenny recalled thinking. “I had never been in a press conference in my life.” But it would be the first of many – he would go on to have four press conferences a day every day for two weeks and not much sleep in between that and working the leak site.

“We were in a territory that nobody had been in before. You’ve got a tunnel system filling with water from a river and how do you stop it? It was scary for a while,” Langford said. “After we saw that there was no real danger, it became a bit lighter.”

At a press conference the day after the flood began, Mayor Daley dropped a bombshell: he played a videotape recorded by a cable company that had been surveying the freight tunnels. The video showed a small crack with water and debris entering the tunnel. The video was also proof that the city had known about the hole in the tunnel for a while.

“Here’s the smoking gun; this was a problem that didn’t need to be a problem,” Langford said. The city had known about the leak.

Months before, a company called Great Lakes Dock and Dredge had been installing new pilings on several drawbridges downtown, including the Kinzie Street Bridge. The pilings were originally supposed to be located elsewhere but were moved to avoid damaging the bridge tender’s house. But the new placement of the pilings, it turned out, had forced a crack in the tunnel wall. One of the city engineers missed the inspection of the new piling placement simply because he couldn’t find parking near the bridge.

“The whole run-up to the Loop flood was, in a way, a comedy of errors,” Moffat said. “The poor tunnel couldn’t wait.” When the city was made aware of the problem from the cable company, they began accepting bids from contractors to fix the problem. The bidding took time.

“That space of time was the difference between having a little leak that could be repaired and a big leak that was going to take a lot of effort to be repaired,” Dixon said.

According to a 1992 Chicago Tribune article, the first estimate for city workers to plug the leak was $10,000. When the city took bids from contractors to repair the tunnel, the estimates were approximately $75,000. The city’s transportation commissioner, John LaPlante, feared it was too high a price. It ended up costing LaPlante his job. Daley would fire several other city officials involved in what was viewed as a too-slow response, though he declined to assume any responsibility himself.

The “Flood Stud” Saves the Day

While fingers were being pointed, Kenny and construction crews were hard at work trying to plug a large underwater hole. Water was pumped out of the flooded buildings. Dive teams were sent in. The engineers borrowed cranes from a project at the United Center. Kenny continued to brief the press every day. He told Chicago Stories it was in his nature to always be honest with the press.

“They tried a lot of different things to plug this hole, and they had a lot of trial and error,” Dixon said. “There was a lot going on, but somehow Kenny managed to explain things so calmly.”

“He was the hero,” Langford said. “To the public, he was the man.” At some point, local columnists dubbed Kenny “the Flood Stud.”

“That was comical,” Kenny told Chicago Stories. “Everybody got a big laugh out of it, but that's stuck with me for a while. These 30 years, people still call me that.”

After two weeks of around-the-clock work, the breach in the tunnel wall was sealed using a special kind of concrete, and the water stopped.

“It was sort of like watching the disaster movie in the last scene…when the music’s playing and everyone’s all happy, and they’re all hugging in the control room,” Langford said. “That’s what it was like when the flow started to ebb.”

Kenny was relieved.

“At the end, obviously I was exhausted from the whole thing,” Kenny said. “But you're not exhausted because you’ve accomplished something.” One night while taking his daughter out to dinner, he walked into a restaurant and got a standing ovation.

In the end, the flood cost almost $2 billion – a bit higher than a $75,000 contractor bid. An estimated 250 million gallons of river water flooded the tunnel system and building basements. While many were able to return to their offices after a few days, some couldn’t return for weeks. Water damage repairs took time.

“The smell of musty basement stayed in a lot of those buildings for months,” Dixon said.

The city’s freight tunnels are still used for fiber optic cables and ComEd cables, but for the most part, they are empty – and dry.

While there may have been several players along the way who allowed a small leak to become a big problem, Kenny said that the legacy of the Loop flood should be the teamwork that went into solving the problem.

“I got a lot of credit for it, but we had one heck of a team of subcontractors, suppliers, [and] engineers,” Kenny said. “We had a great team.”