The day before New Year’s Eve in 1903, a tragedy befell the city of Chicago. In the brand-new, dazzling Iroquois Theater, as a packed crowd of mostly women and children watched the matinee performance of a musical, an arc light ignited a curtain backstage. Though initially unnoticed by the audience, the fire quickly spread. Chaos ensued over the next several minutes, and in the end, 602 people perished in the deadliest single-building fire in United States history. The Iroquois Theater fire is a tragic story of cut corners, desperate escapes, and lessons learned.

An “Absolutely Fireproof” Gem

On November 23, 1903, a new theater opened its doors on West Randolph Street in the Loop. At the time, Chicago was trying to establish itself as a premier city.

“It’s more than a theater to Chicago. It’s a matter of civic pride,” theater historian Stuart Hecht told Chicago Stories. “Whoever’s going to be building that is going to be getting all the breaks and all the publicity, and all of the journalists in town are going to be talking it up like crazy. And they’re going to make sure that people in New York are going to hear it, too.”

With mahogany-and-glass doors, marble-and-gold pillars, and ornamental fixtures, the Iroquois Theater was lauded as a success upon its opening. With a capacity of nearly 1,600, the theater also had a grand staircase – which would later prove to be a fatal design flaw – that connected its three levels.

“The Iroquois Theater was considered a gem in Chicago. It was an amazing feat of architecture. People were raving about how beautiful and opulent it was.”— John Russick, Chicago History Museum senior vice-president

But the road to the theater’s opening was paved with delays. Anthony P. Hatch, author of Tinder Box: The Iroquois Theatre Disaster 1903, told Chicago Stories that labor strikes and shortages complicated the timeline for the opening. A young architect with limited experience named Benjamin Marshall designed the theater and apparently didn’t complete his renderings on time.

“He was very young, and he said he studied every theater disaster previously to avoid any such thing happening with the Iroquois,” Hatch said. “Well, he should’ve done more homework.”

The theater’s owners felt the pressure to open for the fall season. And with Chicago growing rapidly, city officials sometimes struggled to keep up.

“Bureaucrats are having a hard time keeping up with not only giving initial permits, but doing building inspections through the process of the construction phases,” Russick said.

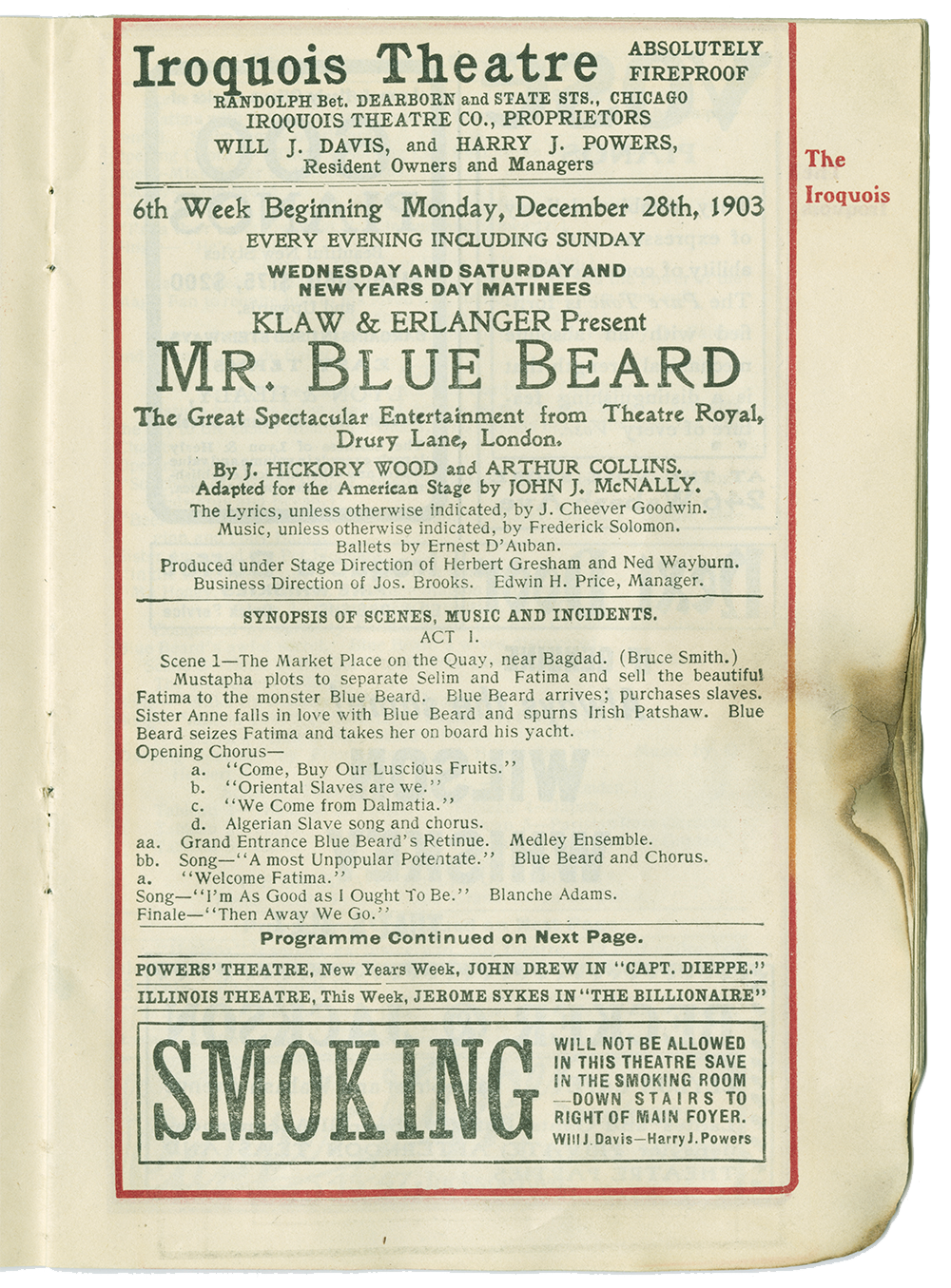

Ready or not, the Iroquois Theater opened that November. In advertisements, the owners touted the building as “absolutely fireproof.” Just over a month after its opening, that would prove to be tragically incorrect.

“Something Out of Hell”

On December 30, 1903, the Iroquois Theater was packed for the performance of a musical called Mr. Blue Beard. Many women and children were in attendance at the matinee, enjoying the three-act show on an icy Chicago day in the midst of the holidays. The show was sold out – and then some. Since the theater had opened behind schedule, the owners and staff were eager to sell tickets. The crowd was well over capacity as people packed into the standing-room-only sections.

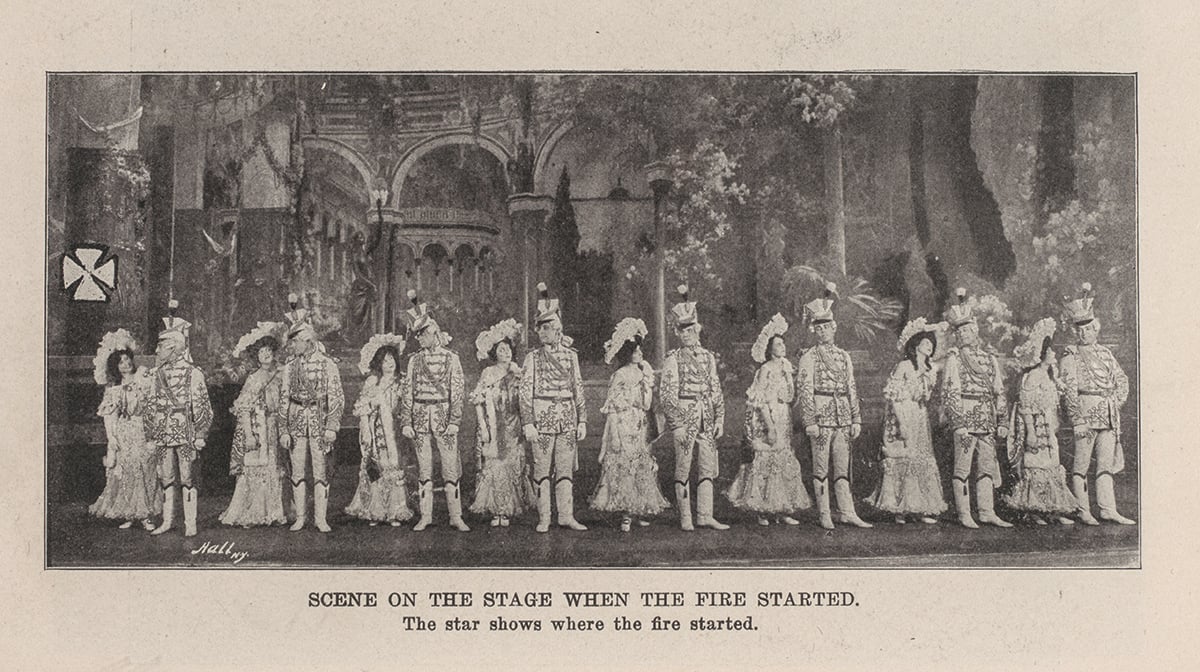

Near the beginning of the second act, a group of performers were on stage performing a song called “In the Pale Moonlight.” An arc light used to create the effect of moonlight sparked a fire, igniting a nearby curtain. Stagehands tried to put the fire out with fire extinguishers they had on hand called “KilFyre.”

“They did not work, and they didn't extinguish the fire. And the fire only grew from there and got out of control very quickly,” Rachel Madden, archivist at Underwriters Laboratories, told Chicago Stories.

The fire climbed up the curtain and began to catch the hundreds of pounds of scenery that hung in the rafters, Hatch said. Not everyone knew what was happening at first, and the performers kept going. The audience didn’t realize the danger. Perhaps, in their view, it was one of the show’s many special effects.

“Many of them sat mesmerized, particularly children who were sitting down front,” Hatch said.

Stagehands tried to lower the asbestos fire curtain, which was designed to delay the spread of the fire, but it got stuck on a light fixture and did not come down. The audience, finally realizing what was happening, began to panic. Eddie Foy, an actor and one of the stars of the show, ran out onto the blazing stage to try to keep people calm. In his autobiography, Foy recounts seeing the audience before the fire broke out.

“It struck me as I looked out over the crowd during the first act that I had never before seen so many women and children in the audience. Even the gallery was full of mothers and children.”- Eddie Foy, Clowning Through Life

The fire quickly grew. People tried to flee, but several obstacles worked against them. The grand staircase that connected all the levels experienced a traffic jam, as people from all the levels were trying to exit at once and converged upon one another. One of the theater’s design flaws – doors that opened inward – prevented people from escaping, as the crush of people against the exit doors made them impossible to open. Some exits were sealed off by iron gates that were installed to keep people in less expensive seats from sneaking down to get a better view. Other elements looked like doors, but were instead decorative. People were trampled in the crowd, while others fell to their death from the balconies.

Skylights that were meant to open to allow heat to escape in the event of a fire had been sealed shut. When actors and stagehands opened a large stage door to escape, the cold air mixed with the hot air inside the blazing theater and created a massive fireball. The flames and gases hit those still in the upper levels, killing many instantly. Foy described it as “a flash and a roar as when a heap of loose powder is fired all at once.”

“They had no chance,” Hatch told Chicago Stories. “It was like a huge fireball that came out. It was already a nightmare, and it just became more.”

Other theatergoers tried to flee down the fire escapes, but they were incomplete or icy and dangerous. While some escaped by crossing to other buildings with the help of onlookers, some fell to their death.

(2) Firemen work to put out the blaze. Image: DN-0001584, Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum

(3) A crowd of onlookers gathered during the fire. Image: DN-0001583, Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum

The flames were swift. Though the estimates vary, the entire ordeal lasted just fifteen minutes. Foy recounts in his autobiography the scene when the fire department arrived.

“When a fire chief thrust his head through a side exit and shouted, ‘Is anybody alive in here?’ not a sound was heard in reply,” Foy writes.

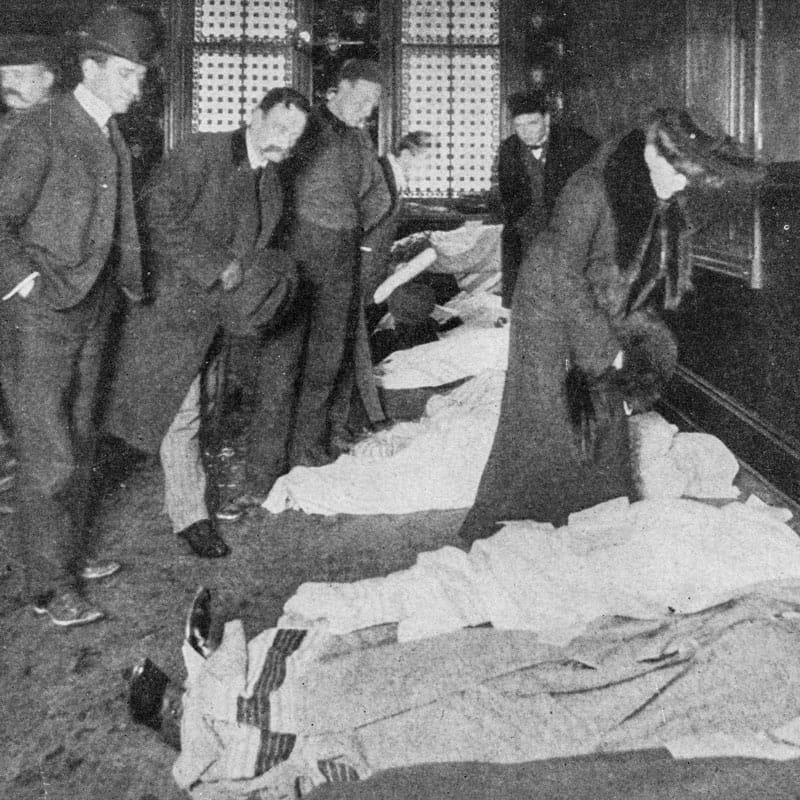

When the firemen and first responders arrived, what they saw horrified them. Bodies had piled up near the exits and in the alleyways. Those who were injured were crying out for help. The once-beautiful theater had been scorched beyond recognition, a shell of its former self.

“Horrific is a word that describes it. It’s unbelievable,” Hatch said. “People described it as like something out of hell.”

“The Terrible Lesson” and What Went Wrong

In the end, an estimated 602 people died. Some families spent the next day – New Year’s Eve – searching for their loved ones in the morgue. Some died weeks later from injuries sustained during the ordeal. The mayor ordered all the theaters to close while officials investigated.

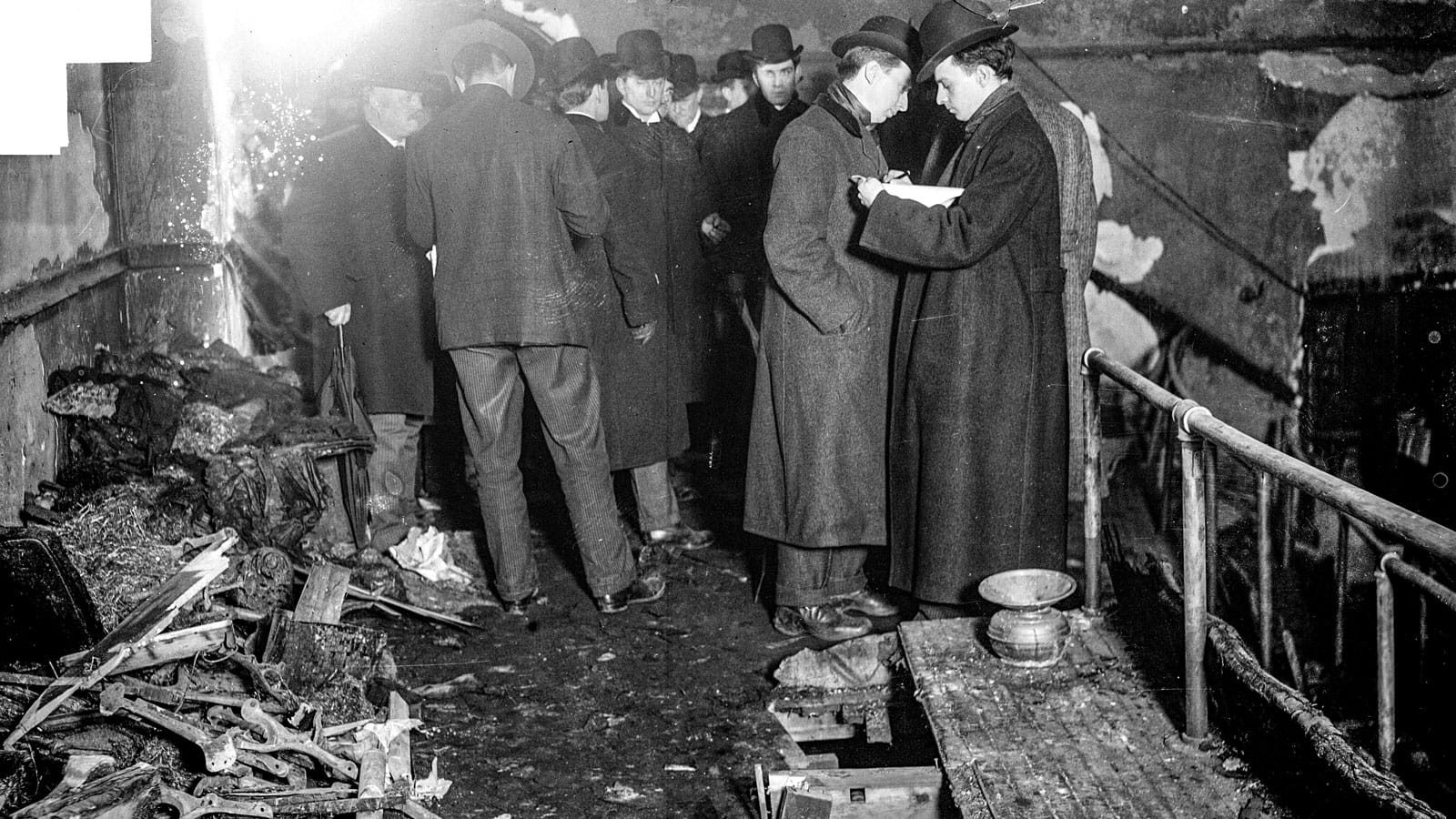

With so many lives lost and so much confusion, many questioned what exactly went so wrong. The mayor, City Council, fire officials, the theater owners, and the architect all deflected blame and pointed fingers at someone else.

“Everybody accused everybody else,” Hatch said. “The owners of the theater deflected criticism and accusations that they had cut corners and didn't have the right kind of equipment or any equipment at all in the theater. They wrote an angry letter to the New York Times…saying that they were being defamed. [They said it] wasn’t their fault.”

But the theater’s design and the lack of proper safety equipment and training played a significant role. In addition to the traffic flow problem brought on by the grand staircase, the gated exits, and the doors that opened inward, there was no emergency lighting and no exit signs in the theater.

“[Architect Benjamin Marshall] didn’t want exit signs to be displayed in the theater because he thought it would ruin the look. He was all for the design,” Hatch said.

The equipment that the stagehands attempted to use to quell the fire when it first broke out was all faulty. The fire extinguishers were useless, and even if the asbestos curtain had been fully lowered, it “was of no value in a fire,” according to one report following the fire. The theater staff was also ill-prepared.

A stagehand had run to the nearest fire station to alert the firemen, costing precious minutes. The faulty KilFyre fire extinguishers, said Madden, created a “false sense of security.”

“The people at the Iroquois thought, ‘Well, we have a fire extinguisher. We don’t need to have a bucket of water on hand and ready. We don’t need to have a lot of fire hose. We don’t need a fire alarm,’” Madden said.

There were some reports that the construction company that built the theater had tampered with evidence after the fire, possibly trying to unseal the skylights that had been nailed shut. But even with 602 deaths, no one was ever held criminally responsible.

“It all kind of fits into a larger picture where the ordinances in the city were not being enforced…The building department wasn’t adequately doing their job. The fire department was not adequately doing their job,” Madden said.

“If the house force had ever had any fire drills, there was no evidence of it in their actions. The stage manager was absent at the moment, and several of the stage hands were in a saloon across the street. No one had even taken the trouble to see that a fire alarm box was located on or near the theatre.”— Eddie Foy, Clowning Through Life

This wasn’t just a Chicago problem, either. Madden said the Iroquois Theater fire was representative of larger problems in the United States during this time.

cket of water on hand and ready. We don’t need to have a lot of fire hose. We don’t need a fire alarm,’” Madden said.“Municipal governments either couldn’t or chose not to exercise the proper authority in holding buildings accountable and building owners accountable and building managers accountable for creating safe buildings,” Madden told Chicago Stories.

(2) Men investigating the Iroquois Theater Fire Image: DN-0001943, Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum

(3) Many of the exits were blocked by grates meant to keep people from sneaking into better seats. Image: DN-0001694, Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum

(4) The skylights that were supposed to allow heat to escape in a fire were nailed shut. Image: DN-0001581, Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum

Many painful truths were revealed in the aftermath of the Iroquois Theater fire.

“[T]he terrible lesson was badly needed,” Foy writes. “In New York at that very moment there were Broadway theaters which had wooden stairways; there were aisles so narrow that not more than one person could pass through them at a time.”

There were, however, important safety protocols and features that came out of the fire that we still use today. For example, the crash bar or panic bar (an emergency mechanism on a door which had been invented after an earlier fire in England) achieved more widespread use. According to a Northern Illinois University article, stricter fire codes, such as capacity limits and equipment and exit signage requirements, were also implemented. But these changes could not make up for the loss of life from the Iroquois Theater fire.

“In my opinion, it shouldn't have happened,” Hatch said. “The people responsible should have been brought to trial. What more can be said, except that the lessons are learned so that we can avoid future accidents like this.”