Warning: This article contains descriptions of violence and includes graphic images.

1885Ida B. Wells Finds the “Real Me” in Writing

Ida B. Wells began her writing career while working as a teacher in Memphis. She joined a lyceum – a kind of intellectual club for literary and artistic minds – founded by other Black teachers. At the end of each lyceum meeting, there were readings from the Evening Star, a newspaper Wells describes as a “spicy journal” in her autobiography, Crusade for Justice. She was surprised when she was offered a writing position with the paper sometime in the mid-1880s. She also began writing for another paper called The Living Way.

For Wells, writing was a true calling, as she explained in her autobiography. “The correspondence I had built up in newspaper work gave me an outlet through which to express the real ‘me’ and I enjoyed my work to the utmost,” she writes. Wells felt she lacked literary verve, but she wanted to write for an audience that could benefit from her direct, succinct style.

I wrote in a plain, common-sense way on the things which concerned our people. Knowing that their education was limited, I never used a word of two syllables where one would serve the purpose. I signed these articles ‘Iola’.

Under her pen name, “Iola,” Black newspapers began to publish Wells’ work in papers around the country. She quickly established herself as a writer on race. Lucy W. Smith, a fellow journalist, dubbed Wells the “Princess of the Press” and wrote, “She reaches the men by dealing with the political aspect of the race question, and the women she meets around the fireside.”

Wells was writing for an audience that had been largely ignored by the mainstream press. According to Michelle Duster’s book Ida B. the Queen, it was “extremely rare” for a Black woman to be writing about race at the time, especially considering so few women were writing for newspapers at all.

“The white press, the newspapers of the day,…ignored Black people unless they were committing crimes or being lynched,” Otis Sandford, Hardin Chair of Excellence in Economic and Managerial Journalism at the University of Memphis, told Chicago Stories producer Stacy Robinson. “So the Black press was vitally important.”

In 1889, Wells became editor and co-owner of the Free Speech and Headlight (which was later shortened to Free Speech). This made her one of only a few women to be both an editor and co-owner of a newspaper, according to Duster. While running that paper, Wells wrote articles that were critical of the conditions of schools for Black children – schools in which she was still teaching.

“You have to think about the type of person who will start writing editorials and news articles about their own employer, but that’s what she was doing,” Nikole Hannah-Jones, reporter for The New York Times Magazine, said in Ida B. Wells: A Chicago Stories Special. Wells’ teaching contract was not renewed the next year, so she focused all of her energy into the newspaper.

1892The Lynching at The Curve

In 1892, Wells’ work took on a sharp new focus.

While I was thus carrying on the work of my newspaper, happy in the thought that our influence was helpful and that I was doing the work I loved and had proved that I could make a living out of it, there came the lynching in Memphis which changed the whole course of my life.

One day in March 1892, a group of Black and white boys got into a fight over a game of marbles outside a store called People’s Grocery in a Memphis district called The Curve. A man named Thomas Moss owned the store. Moss and his wife, Betty, “were the best friends I had in town,” Wells wrote, and she was godmother to their child.

The dispute over the game marbles escalated when the boys’ fathers got involved and got in a fight. The white men vowed to ransack People’s Grocery in revenge. Moss prepared to defend himself along with Calvin McDowell and Will Stewart, who also worked at the store. Several white men, including a sheriff, surrounded and entered People’s Grocery. In the ensuing fight, some of the white men were shot.

Though details in Black newspapers said that Moss and his friends didn’t know law officers were present, the white newspapers called the battle an attack on law officers, calling the Black-owned grocery store “‘a low dive in which drinking and gambling were carried on: a resort of thieves and thugs,’” as Wells quotes it in her autobiography. “So ran the description in the leading white journals of Memphis of this successful effort of decent black men to carry on a legitimate business.”

Moss and the others were arrested, and eventually, a white mob broke into the jail to beat, torture, and lynch Moss, McDowell, and Stewart. Before the mob killed Moss, he had a final message.

Tell my people to go West. There is no justice for them here.

The lynching at People’s Grocery stunned Wells and the Black community in Memphis, leading to weeks of unrest. A judge ordered a sheriff to take over the store.

“Thus, with the aid of the city and county authorities and the daily papers, that white grocer had indeed put an end to his rival Negro grocery as well as to his business,” Wells writes.

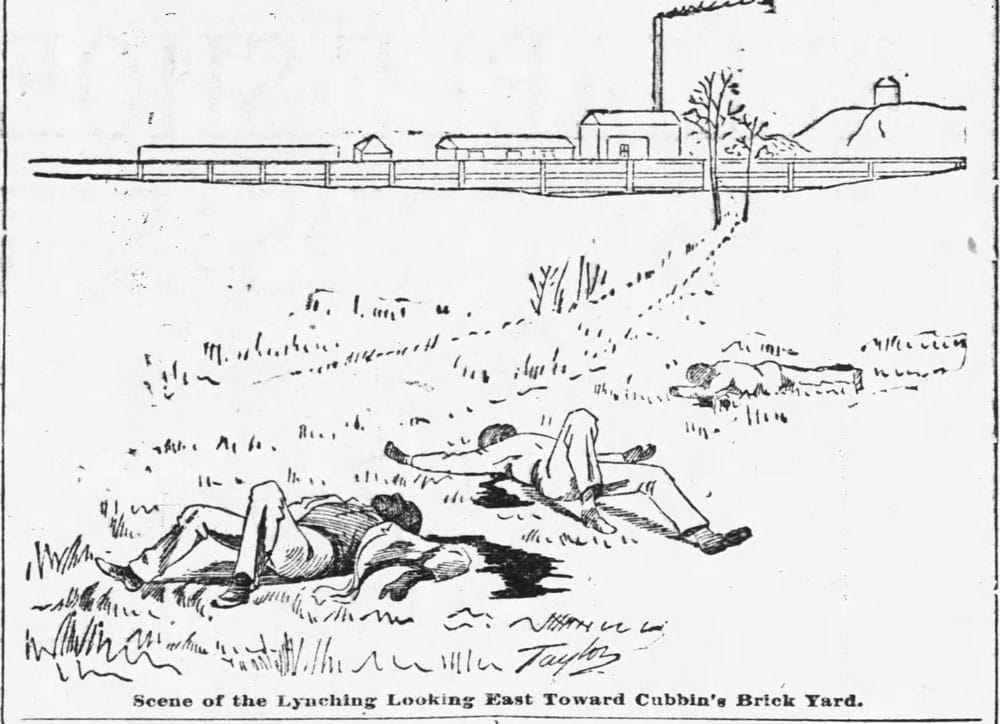

As lynching increased in the 1880s and 1890s, white newspapers and law enforcement were often openly involved. Newspapers would advertise the dates and times of a lynching, and white families would bring their children to watch.

“Lynching was not simply tying a rope around someone’s neck and hanging them, though that is brutal and inhumane enough. Lynching was designed directly to send a message to the larger Black population,” said Hannah-Jones in the documentary. “In the South, in many places, Black people were in the majority. So how does a white minority that has lost power and wants to gain that power back do that when they are in the minority? It was through terrorism.”

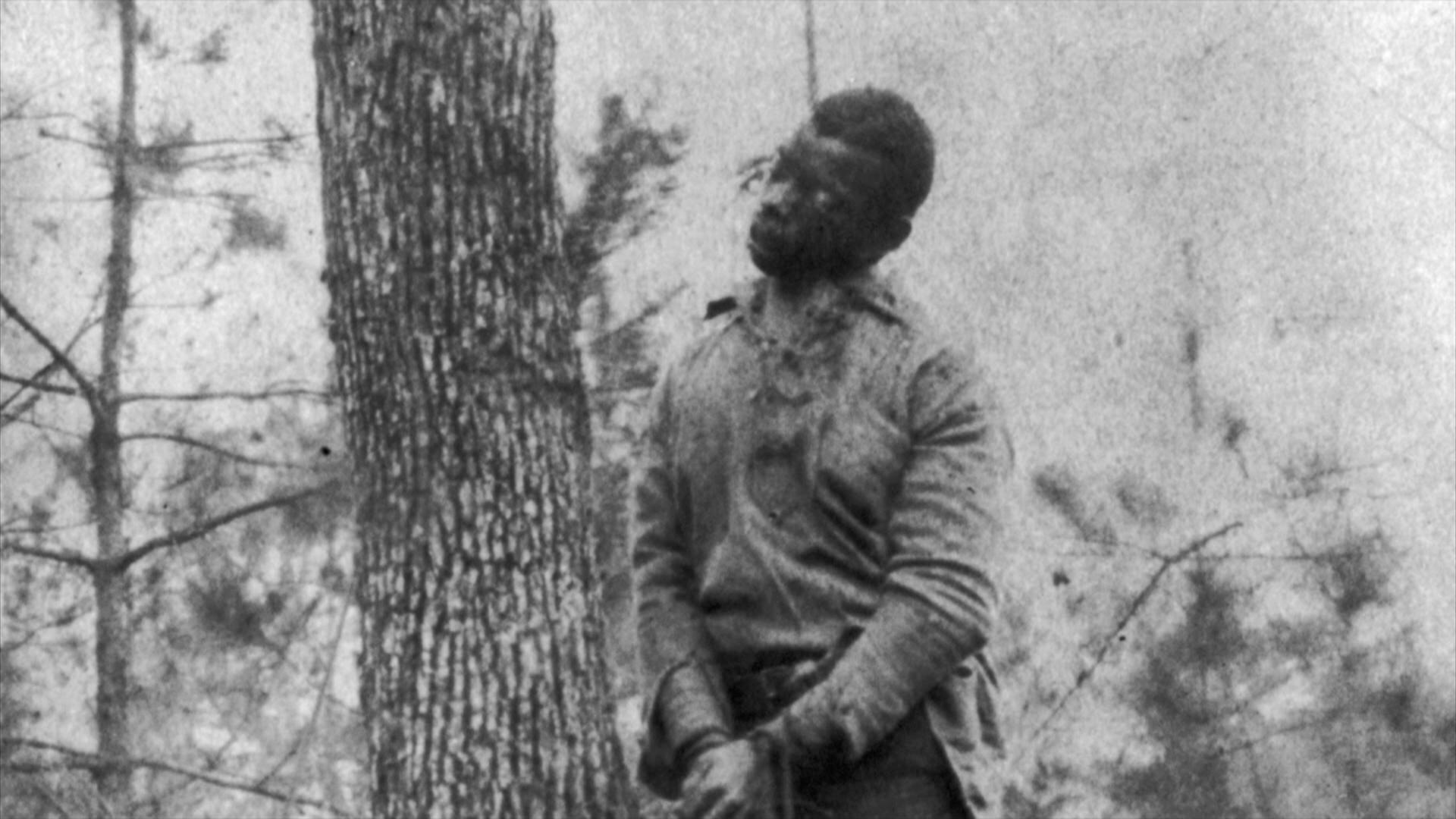

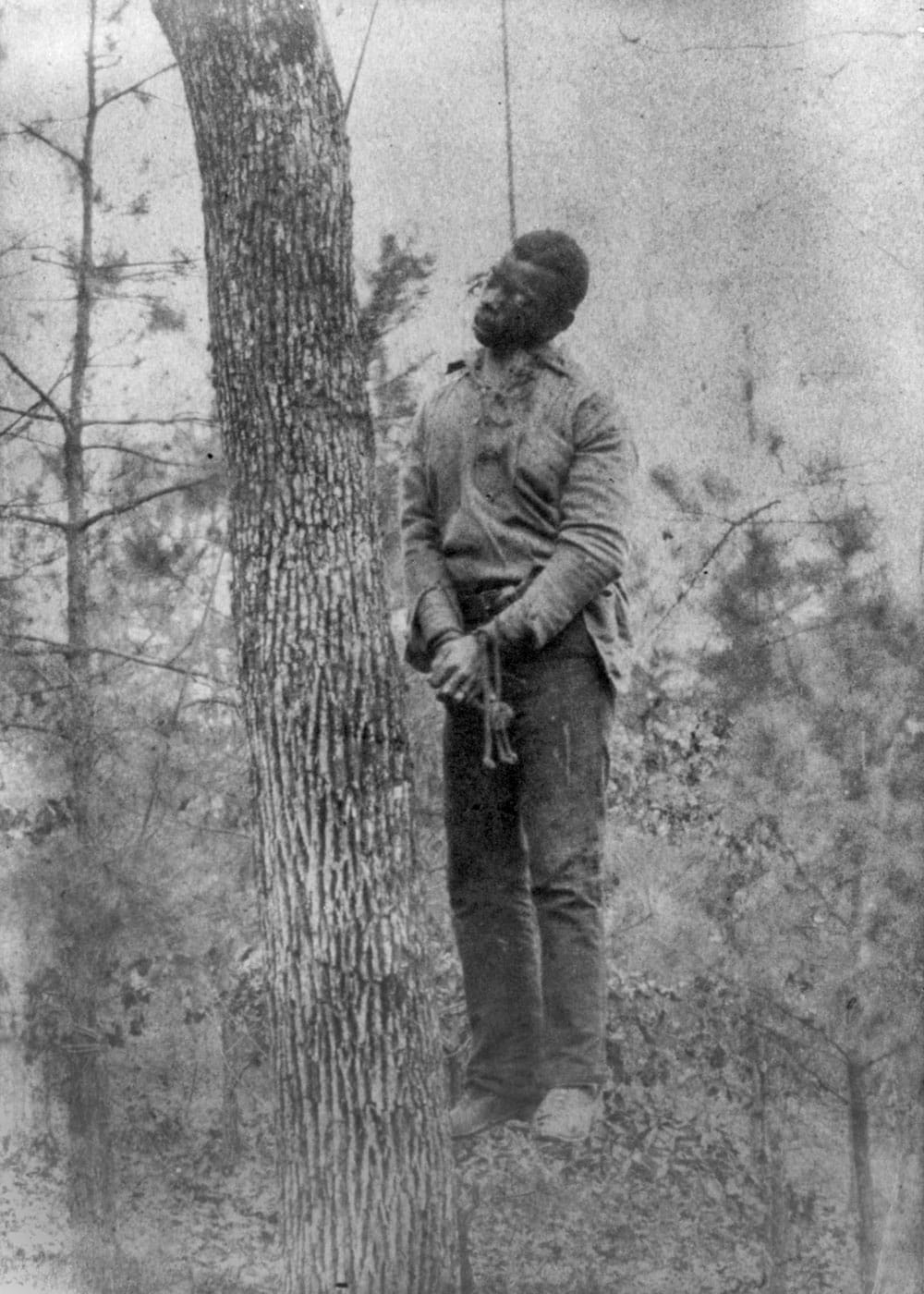

Center: A 17-year-old named Jesse Washington was tortured and lynched in 1916 after allegedly raping and murdering a white woman. His trial lasted less than an hour, and a mob removed him from the courthouse. The murder drew large crowds and was later investigated by the NAACP. Photo: Library of Congress

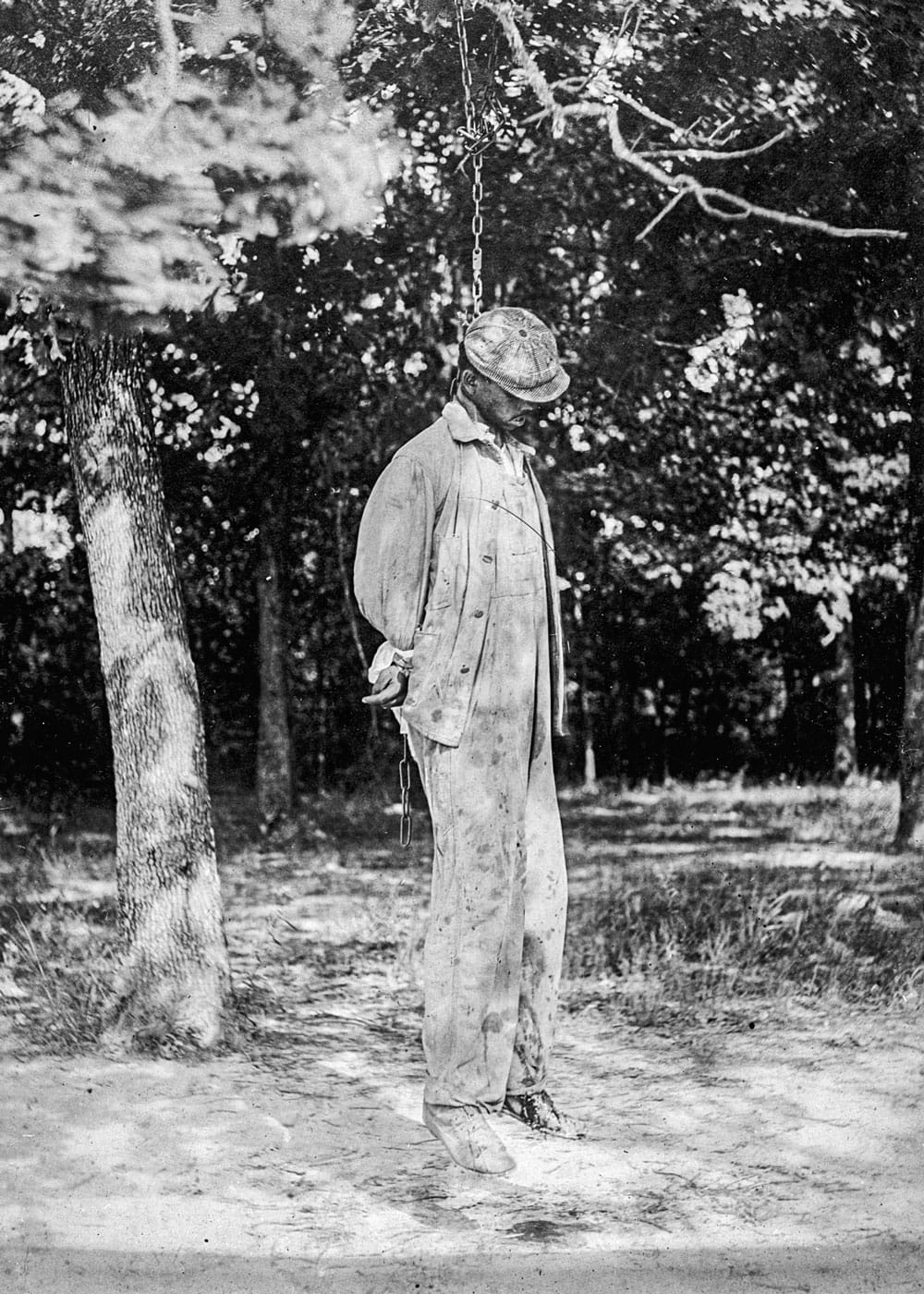

Right/Bottom: A lynching of a man in 1925 Photo: Library of Congress

At the time, a common narrative repeated by white newspapers and law enforcement was that lynching was a punishment for Black men who had allegedly raped white women. According to her autobiography, Wells, like many others, had previously accepted this narrative – that it was punishment for a crime.

But after her friends were lynched having committed no such crime, she began to understand lynching as an “excuse to get rid of Negroes who were acquiring wealth and property and thus keep the race terrorized.” Wells and the Free Speech began publishing editorials calling for boycotts of white businesses and encouraging Black Memphians to leave the city altogether. A couple of months after the murder of her friends, Wells penned an editorial in the Free Speech.

Eight Negroes [have been] lynched since last issue of the Free Speech. Three were charged with killing white men and five with raping white women. Nobody in this section believes the old thread-bare lie that Negro men assault white women. If Southern white men are not careful they will over-reach themselves and a conclusion will be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.

The backlash was swift. While Wells was in New York, an editorial in a white newspaper called for violence against the Free Speech. A mob destroyed the offices and left a note threatening death for anyone who continued to publish the paper. Wells’ friends had informed her that the trains and her home were being watched by white men who planned to kill her. Her friends promised to protect her, but to avoid further bloodshed, Wells stayed away from Memphis, forced to live in exile.

1892Exposing “Southern Horrors”

Wells’ Free Speech editorial was just the beginning. She continued to investigate the truth about lynching, working to uncover facts to dispel the “thread-bare lie.”

They had destroyed my paper, in which every dollar I had in the world was invested. They had made me an exile and threatened my life for hinting at the truth. I felt that I owed it to myself and my race to tell the whole truth.

“One of the things that always attracted me to her as a subject is that she just seems fearless, not just about her physical self, but she was also fearless in the courage of her convictions,” said Paula Giddings, author of Ida: A Sword Among Lions.

Wells spent the next several years implementing investigative journalism techniques to document and track the data surrounding lynchings all over the United States.

“Investigative journalism was a modern innovation of that period, and so was the use of statistics,” Giddings said. “One of the things she does is to aggregate all the cases of lynchings that she can find in the newspapers…And then she has her own data because she's investigating lynching herself.”

Hannah-Jones said in the documentary that, prior to Wells’ work, there was no real sense of how many lynchings occurred in America. Wells began to keep what were basically spreadsheets.

In October 1892, she published a pamphlet called Southern Horrors, which she described as “a true, unvarnished account of the causes of lynch law in the South.” She recounted dozens of lynching stories, condemning the “malicious and untruthful white press” and calling lynch law “that last relic of barbarism and slavery.”

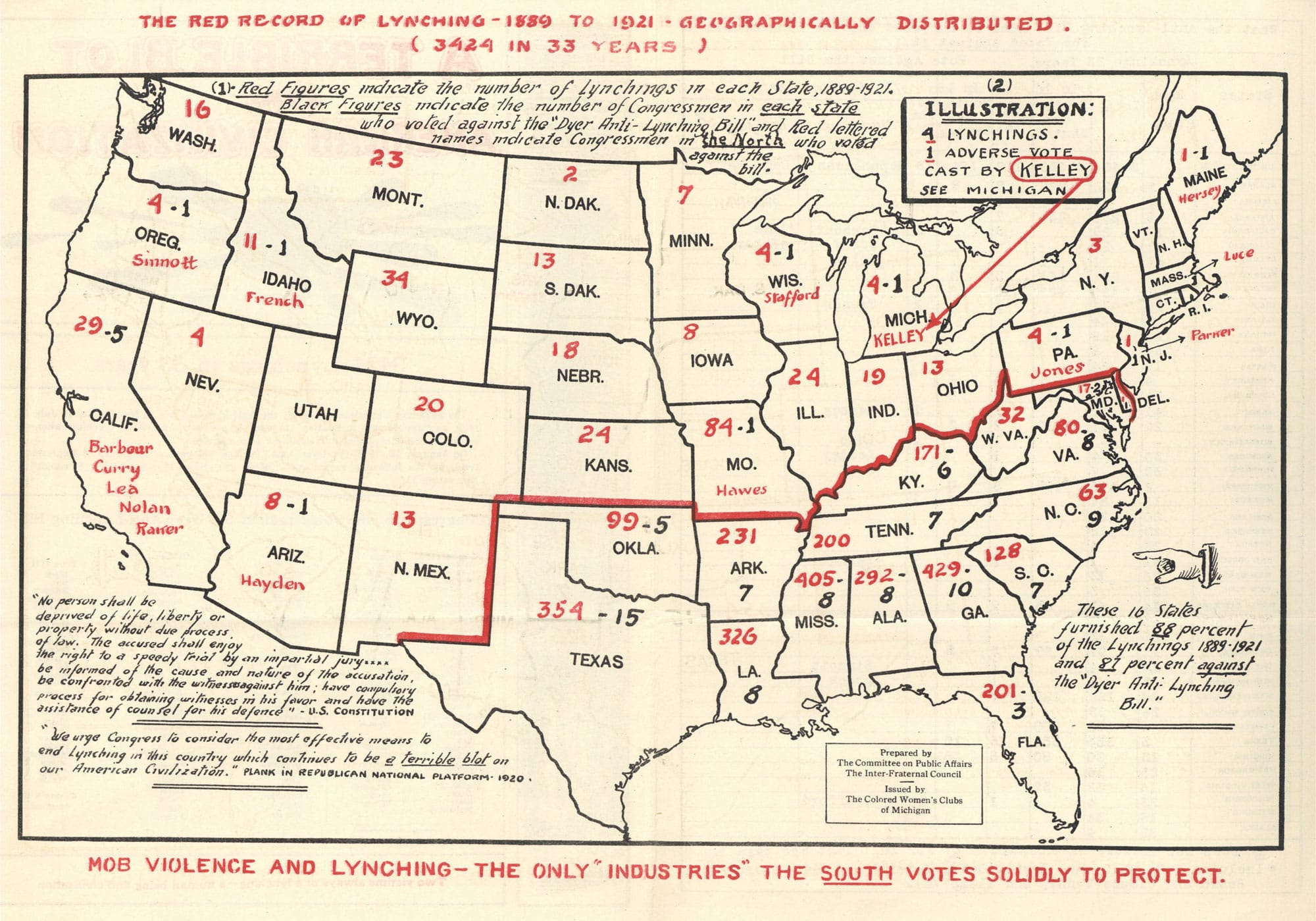

Right/Bottom: Ida B. Wells created this map of lynchings that was submitted to Congress as part of a 1922 anti-lynching bill. The bill did not pass. Credit: National Archives

In her investigation of 728 lynchings in Southern states, Wells found that only a third of the victims had actually been charged with rape, “to say nothing of those of that one-third who were innocent of the charge.”

“What she shows is that lynching is really just an effort to suppress Black people, to contain them, and to make sure that they're not competitive in the new industrial economy,” Giddings said.

The pamphlet was eye-opening for many. Like Wells herself, many Black Americans had believed the white press’s narrative of lynching as punishment for a crime. In her autobiography she recounts how Frederick Douglass, for one, was astonished by Wells’ reporting. In a letter published at the beginning of Southern Horrors, he praises her.

You give us what you know and testify from actual knowledge. You have dealt with the facts with cool, painstaking fidelity and left those naked and uncontradicted facts to speak for themselves. Brave woman! you have done your people and mine a service which can neither be weighed nor measured.

She wrote another pamphlet called The Red Record in 1895, which outlined the increase in violence against Black people following Reconstruction and further investigated lynching. In one section of that pamphlet, she listed examples of some of the reasons people were lynched, ranging from an alleged theft of hogs to a mere verbal disagreement with a white person. In a pamphlet published in 1900 called Mob Rule in New Orleans, she examined the brutal murder of a Black man named Robert Charles and the subsequent race riots in New Orleans.

She continued to dispel the myth that Black men were lynched for sexual violence against white women, asserting that the relationships were sometimes consensual, but white mobs wanted to “defend the honor” of white women. She also embarked on speaking tours to campaign against lynching, first in New York and Philadelphia, and ultimately in England in 1893 and 1894.

“The stuff that she starts talking about – nobody is talking about rape and interracial sexuality in this period,” Giddings said. “So she seems pretty fearless on all fronts.”

2019Ida B. Wells’ Legacy in Journalism

For decades following her death, Wells’ legacy as a journalist and activist went largely unrecognized. According to Giddings, part of the reason is that racism and sexism downplayed her role in getting things done. She added that Wells’ direct writing style and her lack of fear in confronting people with whom she disagreed often put her at odds with fellow activists.

“She was ignored not because she was inconsequential, but because she was controversial,” said Giddings.

Wells’ descendants, including her great-grandchildren Michelle and Dan Duster, have worked in recent years to get Wells’ work recognized in Chicago and beyond. In 2019, the city of Chicago changed the name of Congress Parkway to Ida B. Wells Drive, making it the first Chicago city street to be named for a Black woman.

In 2020, Wells was posthumously recognized with a Pulitzer Prize in the Special Citations and Awards Category “for her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching.”

Hannah-Jones, whose Twitter profile name is “Ida Bae Wells” as a nod to the late journalist, co-founded the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Journalism. The society is “dedicated to increasing and retaining reporters and editors of color in the field of investigative reporting.” On the same day that Ida B. Wells was awarded the Pulitzer Prize, Hannah-Jones won the Pulitzer Prize for Commentary for her work on The 1619 Project.

“When I found out that I had won the Pulitzer on the same day as my spiritual godmother, Ida B. Wells, a woman who did not receive that type of recognition in her life and never would have, I cried like a baby,” Hannah-Jones said in the documentary.

Ida B. Wells would continue to use the power of her pen in the decades to come as she married lawyer Ferdinand Barnett, had children, and settled in Chicago. She shifted some of her focus to political work, but she never stopped being an anti-lynching advocate, and she never stopped writing.