In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, settlement houses were “reform institutions,” often placed in immigrant neighborhoods to help alleviate poverty and provide social services, according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago. In Chicago, Hull House is a well-known settlement house for immigrant women and children. Jane Addams – an activist, social reformer, and friend to Wells – founded Hull House in 1889.

The Negro Fellowship League first emerged following the Springfield race riots of 1908. Over a two-day period that summer, there was wave of violence against the Black community at the hands of a white mob. It followed the alleged assault of a white woman by two Black men. The mob of nearly 5,000 people looted and destroyed Black-owned businesses, assaulted people, and lynched two elderly Black men, Scott Burton and William Donegan. At least seven people were killed before the Illinois National Guard restored order.

Wells wrote that the murders “under the shadow of Abraham Lincoln’s tomb” led to a passionate discussion about racial oppression at her Sunday Bible group. The group continued to meet every Sunday.

That was the beginning of what was afterward to be known as the Negro Fellowship League…Here we discussed matters affecting the race and invited prominent persons who might be in the city to address us.

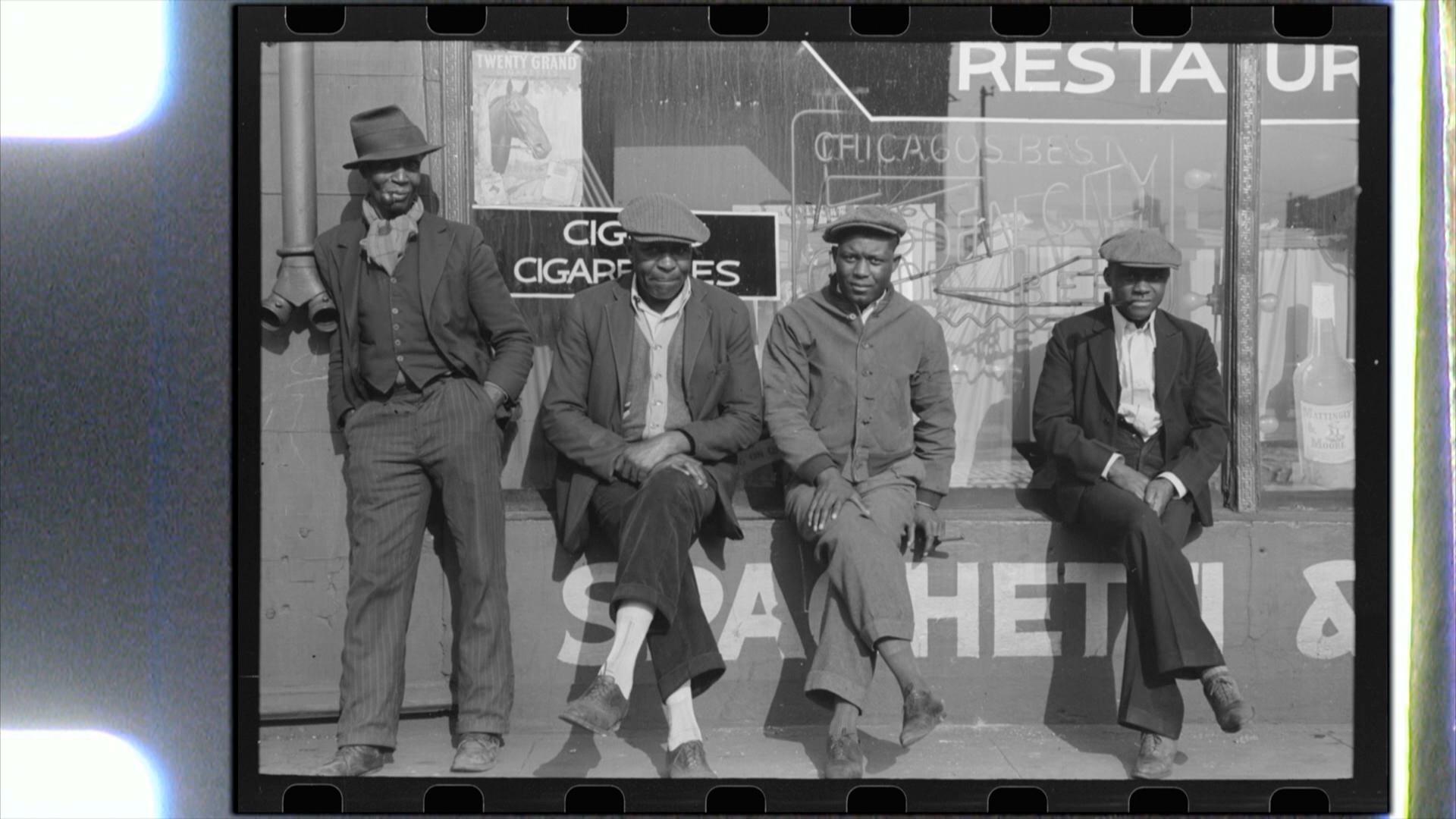

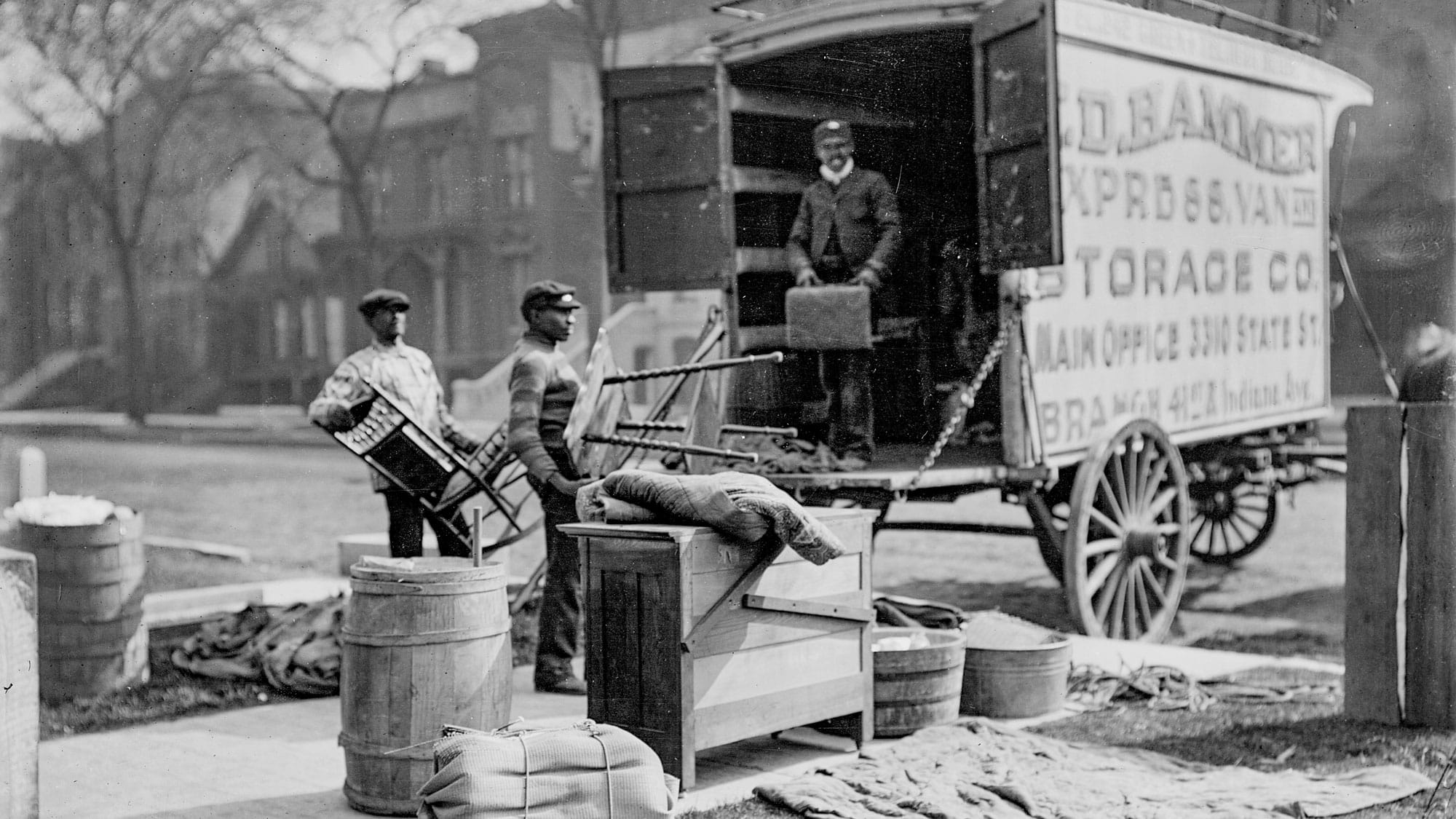

Though the group formed a few years before what historians consider the official start of the Great Migration, Black migrants were already beginning to leave the South in increasingly large numbers.

“She was a probation officer with the county and had seen and heard firsthand the plight of young Black people who had come to the North and were having trouble adjusting to urban life, beginning with earning a living,” historian Christopher Reed told Chicago Stories producer Stacy Robinson.

Since many young men were coming from agricultural jobs in the South, they often had a different skillset than the Northern job market required, and they lacked a social support network.

“There started to be some bad backlash against this flood of Black people coming from the South to the North,” Michelle Duster, author great-granddaughter of Ida B. Wells, told Robinson. “Then there started to be this [reaction] like, ‘Whoa, there are too many of you, and we’re not going to let you live in our neighborhoods, and we’re not going to let you work over here.’”

At this time, the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) did not admit Black men, so the group that emerged from Wells’ Bible study created its own space. On May 1, 1910, the Negro Fellowship League Reading Room and Social Center opened at 2830 South State Street. With a small library, a job center, and, later, a dormitory, its goal was to be a social service center for young Black men who had recently arrived in Chicago from the South. Wells used her salary as a probation officer to pay for the rent for the space.

It was located in the lively entertainment district along State Street known as The Stroll, with theaters, saloons, and gambling. Wells writes, “There was not a single uplifting influence along the whole length of State Street, and I did not think that our Christian forces should leave State Street to the devil.” Some supporters of the Negro Fellowship League voiced “great objection” to the location, thinking it “beneath their consideration.” Wells disagreed.

I told them that I was convinced that they needed State Street as much as State Street needed them. Most of my young men had come from good families and other sections of the country. Many of them were well educated. Some were taking courses in law and medicine while they earned their daily bread by night work in the post office.

In her autobiography, Wells tells how, on their very first day, there was a “disturbance” that disrupted the program they put on for the community. A group of men who had been drinking were shooting dice. A janitor suggested they call the police, but Wells saw it as an opportunity.

“I said, ‘I would rather you would come into the meeting. We have come over here to be your neighbors and we will hold meetings every Sunday. Do come in.’” Wells writes. She asked them to shake on it, but the men were afraid to get her white gloves dirty. But they “repeated their promise to come next Sunday.”

According to Paula Giddings’ biography, Ida: A Sword Among Lions, within a year, the Negro Fellowship League had 40 to 50 patrons a day and had placed 115 men in jobs. It would go on to help a thousand more in the decade that followed, Duster writes.

With the help of Ferdinand Barnett, Wells’ husband and lawyer, the center also provided legal aid for young men accused of crimes. One such man was Steve Green, a tenant farmer from Arkansas. Green had fled to Chicago in 1910 after allegedly killing his landlord in a dispute. He was eventually arrested in Chicago, and his case came to Wells’ attention after he attempted suicide in custody. “The report in our daily papers said that he knew he would be lynched if he was taken back,” Wells writes.

A legal battle to get Green extradited to Arkansas ensued, but Wells managed to get Green out of town. Green returned when the sheriff gave up on the extradition, staying in the dormitory at the Negro Fellowship League. “The last I heard of him he was still here in Chicago,” Wells writes. “He is one Negro who lives to tell the tale that he was not burned alive according to program.”

It came to be the regular work of the Negro Fellowship League to take up all matters affecting the interest of our race.

In addition to being a settlement house, the Negro Fellowship League was the meeting location for the Alpha Suffrage Club, the suffrage organization founded by Wells to engage Black women voters. It was also where government intelligence agents once confronted Wells for creating a button to commemorate the hanging of 13 Black soldiers.

In 1917, the all-Black Third Battalion of the 24th United States Infantry was stationed in Texas. As the soldiers encountered Jim Crow racism, a series of incidents occurred, culminating in the arrest of a Black soldier who allegedly intervened in the arrest and mistreatment of a Black woman at the hands of white police. A rumor had spread to the battalion that a fellow soldier had been killed, sparking a gun battle between the battalion, local police, and white residents. The battle resulted in the deaths of 16 white people, including five policemen, and four Black soldiers. In the largest court martial in U.S. military history, 64 soldiers were tried and 13 were hanged for their role in what was described as a “riot.”

To honor them and draw attention to the event, Wells created buttons. Not long after a reporter came knocking to ask about the buttons, two intelligence officials showed up at the door of the Negro Fellowship League, telling her she could be arrested for treason. She told them the government deserved to be criticized. She writes about the exchange in her autobiography:

“Well,” said the shorter of the two men, “the rest of your people do not agree with you.” I said, “Maybe not. They don’t know any better or they are afraid of losing their whole skins. As for myself I don’t care. I’d rather go down in history as one lone Negro who dared to tell the government that it had done a dastardly thing than to save my skin by taking back what I have said. I would consider it an honor to spend whatever years are necessary in prison as the one member of the race who protested, rather than to be with all the 11,999,999 Negroes who didn’t have to go to prison because they kept their mouths shut.

Nothing ever came of the exchange, but as Michelle Duster writes in Ida B. the Queen, the FBI kept a file on Wells, calling her “one of the most dangerous Negro agitators.”

After ten years, the Negro Fellowship League closed its doors in 1920. Wells had struggled to get the same kind of financial support that Jane Addams’ Hull House received.

“I don't know if she originally thought she would be doing this work by herself,” Duster said in the documentary. “I think she expected and was hoping for other people to be as outraged as she was and to get in the trenches and fight.”

Better-funded organizations, such as the Chicago Urban League and the Wabash YMCA (which, unlike the previous YMCA branches, was formed to serve Black men) eclipsed the Negro Fellowship League.

“These were momentary setbacks. There would be other accomplishments throughout her career,” historian Charles Branham told Robinson. “This is a woman who had been repeatedly defeated, excluded, repudiated, libeled, and she always bounced back.”