1897Chicago’s First Black Kindergarten

In 1897, Wells established the first Black kindergarten in Chicago. A few years prior, Wells had established a civic organization for Black women that would later be called the Ida B. Wells Club – the first club of its kind, according to historian Anne Meis Knupfer. With that club, Wells sought to improv access to education in her community.

“She wanted to understand the nature of African American progress, promote African American progress, and serve the needs of those who would create in the future,” historian Charles Branham told Chicago Stories producer Stacy Robinson. “That's why she founded the first kindergarten for African Americans, because she was always looking, not so much at the past, but into the future.”

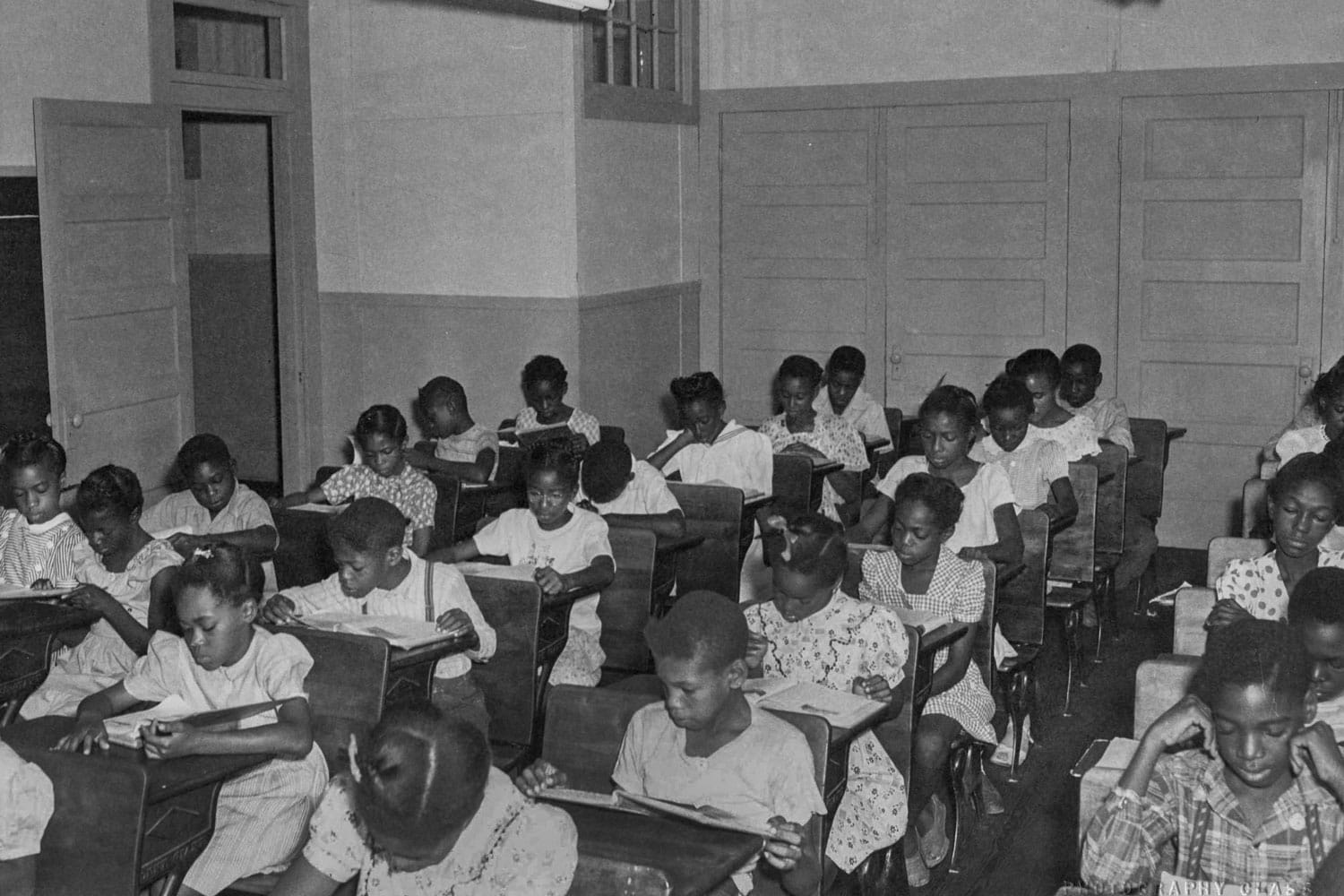

According to Paula Giddings, author of Ida: A Sword Among Lions, more kindergartens began to open as a kind of “trend” and were particularly appealing to Black families who had a higher proportion of working mothers. At the time, the Armour Institute had opened a kindergarten on the South Side near the “Black Belt,” where most of the city’s Black residents lived. But enrolling white children was often prioritized.

Wells set about opening the first kindergarten for Black children at Bethel AME Church but was surprised when the community was hesitant.

“They insisted that if we established a kindergarten in a colored district it would be drawing the color line, and would make it impossible for colored children to be accepted at the Armour Kindergarten,” she writes in her autobiography. “To say that I was surprised does not begin to express my feeling. Here were people so afraid of the color line that they did not want to do anything to help supply the needs of their own people.”

Wells said there was a “battle royal” over the topic, but her club was “very loyal in its support,” and they were able to raise money to open the kindergarten. Not long after it opened, Wells vowed to step out of public life. Pregnant with her second child, Wels found that “motherhood was a profession by itself.” In her autobiography, she expresses that she was always uncertain about having children, having raised her younger siblings. She had been intent on focusing on her work, but called motherhood a “wonderful discovery.”

But following another lynching in South Carolina, she writes, “It seems that the needs of the work were so great that again I had to venture forth.”

1900Challenging the Chicago Tribune

A few years later, Wells took up the issue of education once again when the Chicago Tribune published a series of articles “tending to show the benefits of a separate school system for the races in Chicago,” Wells writes, pointing out that the articles failed to quote any Black families in the school system. At the time, Chicago’s schools were integrated.

Wells writes in her autobiography that her husband, Ferdinand Barnett, came home from work “exasperated” about the topic, too. The couple discussed what they should do about it.

There must always be a remedy for wrong and injustice if we only know how to find it.

Wells wrote a letter to the editor of the Tribune, asking if he would be willing to hear from Black Chicagoans on the matter, but the letter went unanswered. Wells then decided to show up at the Tribune offices to confront the editor. They had “quite a chat,” Wells recounts, as the editor expressed a racist viewpoint beyond just that of education. “He said that he did not believe that it was right that ignorant Negroes should have the right to vote and to rule white people because they were in the majority.” Wells thought the situation looked bad, as the editor said he would publish her letter “when they got around to it.”

Wells wanted to stage a boycott of the Tribune. Believing that “the Negro had neither numerical nor financial strength which could be used in the race’s behalf,” she sought the help of white leaders who would be sympathetic to her cause. She recruited her friend, activist, and social reformer Jane Addams to help. Addams delivered, calling a meeting at Hull House in which Wells delivered her case to white social workers, faith leaders, lawyers, and editors of other papers. Addams formed a committee of seven people to “wait upon” the Tribune.

“I do not know what they did or what argument was brought to bear,” Wells writes in Crusade for Justice, “but I do know that the series of articles ceased and from that day until this there has been no further effort made by the Chicago Tribune to separate the schoolchildren on the basis of race.”