1891Suffrage in Illinois

In 1891, just a few years before Wells settled in Chicago, women in Illinois won the right to vote in school board elections. According to Lori Osborne, director of the Frances Willard House Museum in Evanston, these small steps were part of a strategy.

“This idea that women would gain the right to vote incrementally, with partial ballots on selected elections that were in their wheelhouse – so, related to their roles as mothers, wives, daughters, or traditional women’s roles – was something that was developed and really promoted in Illinois,” Osborne said.

It would take another 20 years before Illinois women gained more voting rights. In 1913, the Illinois Presidential and Municipal Suffrage Bill passed, allowing women to vote for president and in municipal elections, but not for statewide offices.

“Women like Ida B. Wells are well aware of this new power. Women across the state are voting across race lines, across all sorts of lines that would normally have divided them,” Osborne said. Prior to the Civil War, the women’s and abolition movements often worked together. Abolitionists such as Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Sarah Parker Remond, and Frederick Douglass worked with the early suffrage movement. But during Reconstruction there were sometimes “calls for unity” between Northern and Southern suffragists, Osborne said.

“What this often seems to lead to is compromises by Northern activists with Southern racism for the purposes of a reconciliation, which ends up disenfranchising and disempowering the Black community,” said Osborne.

Wells would emerge in the next generation of activists and would do so as a vocal opponent of the racism she experienced firsthand as a Black suffragist.

1894The Dispute Between Ida B. Wells and Frances Willard

According to Osborne, Wells was unequivocal in her expectations that the white women in the suffrage movement must embrace Black women and stand by them in their fight against racial discrimination and violence.

“She is coming out of the Reconstruction era with the hope and the expectation of being respected and treated as an equal partner and an equal player,” Osborne said. Wells was unafraid to point out racism when she saw it within the suffrage movement. In the early 1890s, a public dispute between Wells and Frances Willard, president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), embodied the struggle of Black women to be recognized as equals in the struggle for suffrage.

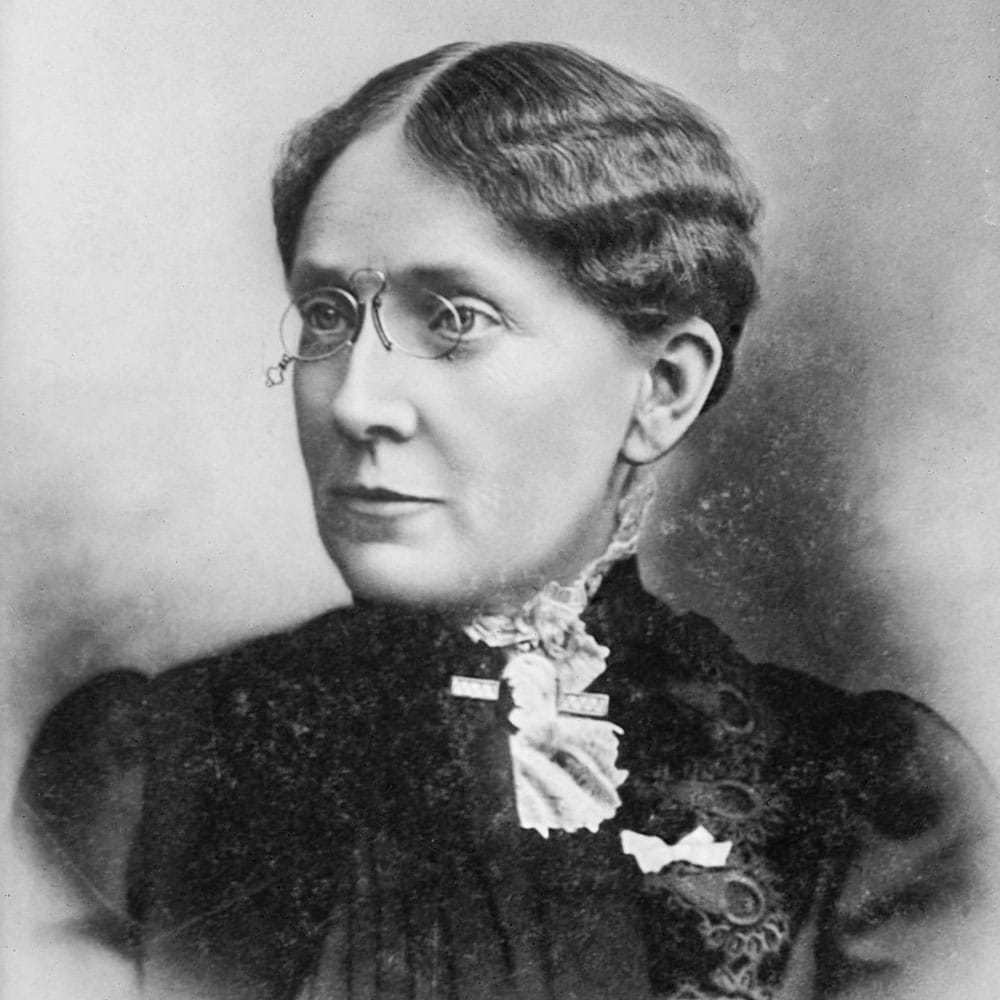

Willard, who lived in Evanston and was a generation older than Wells, became a national figure in the late 19th century as she used her platform as WCTU president to endorse and fight for women’s suffrage. According to the Frances Willard House Museum’s digital exhibition, Truth-Telling: Frances Willard and Ida B. Wells, “Willard argued that the only way women could protect their homes and families from the threat of alcohol was to win the right to vote and make prohibition the law, along with other reforms to improve women’s lives.” Black women were among the WCTU’s thousands of members across the United States.

In 1890, Willard made racist remarks in a newspaper interview while she was traveling with the WCTU. Despite claiming she had “not an atom of race prejudice,” Willard wrongfully blamed Black voters for a defeat of temperance reform in the South. She described Black men as the “great dark-faced mobs whose rallying cry is better whiskey and more of it…The grogshop is their center of power. The safety of women, of childhood, of the home is menaced in a thousand localities at this moment, so that men dare not go beyond the sight of their own roof-tree.”

The comments came at a time when Willard was attempting to grow her organization in the South, often leading her to refuse to take up racial issues to appease the racist views of Southern suffragists.

In 1894, both Willard and Wells visited England – Wells on an anti-lynching speaking tour, Willard to promote suffrage and temperance. In an interview, Wells resurfaced Willard’s previous racist comments, condemning them as dangerous and reinforcing the stereotypes behind lynching. This kicked off a public dispute in the press between the two women. Willard’s comments were mostly defensive, pointing to her family’s abolitionist history as proof that she couldn’t be racist, while Wells continued to question her moral leadership.

Wells continued to hold Willard accountable for her comments, even devoting a chapter of A Red Record, her 1895 investigative pamphlet on lynching, to the dispute. In it, she details the war of words between the women and stands firm in her position:

I desire no quarrel with the W.C.T.U., but my love for the truth is greater than my regard for an alleged friend who, through ignorance or design misrepresents in the most harmful way the cause of a long suffering race….

Wells calls the WCTU “the most powerful organization of women in America,” underscoring the significance that a condemnation of lynching by the group would hold.

“Because the WCTU is a grassroots organization, it is led by all the little chapters and all the little towns all over the United States,” Osborne said. “So when it supports something, it's pretty important.”

WCTU eventually passed anti-lynching resolutions in 1894 and 1895, but according to Truth-Telling, Willard never apologized to Wells for her initial comments.

1913The Alpha Suffrage Club and the 1913 Suffrage Parade

In 1913, Wells co-founded a group called the Alpha Suffrage Club with the white suffragists Belle Squire and Virginia Brooks. At this point, Illinois women were on the cusp of gaining restricted suffrage that would allow them to vote in presidential and city elections, but not statewide elections, such as those for governor or senator.

When I saw that we were likely to have a restricted suffrage, and the white women of the organization were working like beavers to bring it about, I made another effort to get our women interested.

The goal of the club was to engage Black women and mobilize voters, since many white women in the movement either chose to emphasize women’s issues over race or were discriminatory altogether. Some Black men were also resistant to the idea, fearing that the extension of suffrage to women would weaken their own already tenuous voting rights. As Wells recounts in her autobiography, as the women in her club attempted to persuade the community to support women’s suffrage, “The men jeered at them and told them they ought to be at home taking care of the babies. Others insisted that the women were trying to take the place of men and wear the trousers.”

In March 1913, Wells and other members of the Alpha Suffrage Club went to Washington, D.C. to participate in a national suffrage parade that was to take place the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Organized by the National American Women Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and led by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, the march drew more than 5,000 women, according to Paula Giddings’ biography, Ida: A Sword Among Lions.

But before the parade, several white suffragists refused to participate if the march was integrated. They instead asked Wells and other Black suffragists to march in the back. Wells, Squire, and Brooks wouldn’t stand for it and debated with the Illinois delegation and NAWSA leaders.

When I was asked to come down here, I was asked to march with the other women of our state, and I intend to do so or not take part in the parade at all.

Ultimately, NAWSA denied Wells’ request, fearing white women would drop out and deplete their numbers. But when the march began, Wells emerged from the crowd and joined the Illinois delegation alongside her friends.

“Ida B. Wells is enormously important to the suffrage movement for her role in the parade,” historian Joan Johnson told Chicago Stories producer Stacy Robinson. “It is a very visual reminder of what is happening in terms of the [lack of] willingness of white suffragists to work with and to fight for women of color.”

Just two years after the suffrage march in Washington, the Alpha Suffrage Club played a major role in electing Chicago’s first Black alderman, Oscar De Priest.

At a time when the movements for racial and gender equality were separate and at times competing, Wells fought for both. According to Osborne, there is “no question” that Wells was ahead of her time when it comes to the intersection of race and gender.

In Wells’ autobiography, she recounts a conversation she had with her “dear good friend” Susan B. Anthony. Recalling how she once declined to help a group of Black women who wanted to form their own suffrage organization and asked Frederick Douglass not to attend a suffrage conference in order to placate Southern suffragists, Anthony asked Wells if she had been wrong to do so.

“I answered uncompromisingly yes, for I felt that although she may have made gains for suffrage, she had also confirmed white women in their attitude of segregation,” Wells writes.

Similarly, after the incident at the 1913 suffrage parade, Illinois lawyer and suffragist Catharine Waugh McCulloch wrote Wells a letter to express support and invited her to speak in Evanston. In her response, Wells had a clear message.

Our women should be as firm in standing up for their principles as the Southern women are for their prejudices.

“I find that to be just such an important and inspiring reminder today that it's not enough to not be racist. But we talk more now about being anti-racist,” Johnson said. “And I think that's what Ida is saying. It's not enough. We have to actually stand up for our principles.”