For decades, Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church in the South Chicago neighborhood was a cultural center for the community’s Mexican-American families. In that church, families celebrated baptisms, confirmations, weddings, and other major milestones. But after the United States entered the war in Vietnam, funerals for 12 parishioners would take place at Our Lady of Guadalupe – a loss greater than in any other parish in the country. Many of the family members and friends of the young men who died, as well as other veterans, still feel the impact of that tragedy today. But what emerges from a memorial to the young men in the church’s nearby parking lot is a story of love, resilience, and memory.

“It Was a Special Place”: Our Lady of Guadalupe and the South Chicago Community

The first significant arrival of Mexican migrants to Chicago took place in the 1910s as many sought refuge from the violence of the Mexican Revolution. Civil rights and military historian Bill Luna told Chicago Stories that many migrants came to Midwestern cities because of the job opportunities. Unlike in California or the American Southwest where agriculture was the main industry, migrants worked in steel mills, packing plants, and railroads in the Midwest.

“Mostly the steel mills…provided a good living for individuals,” Luna said. “You didn’t have to be fluent in English.” Workers often faced discrimination, inflated rent, and unsafe working conditions, and though the pay wasn’t necessarily high, the ability to work long hours meant higher wages.

Over the next several decades, Mexican immigrants settled in enclaves all around Chicago, including the Southeast Side of the city in a community area called South Chicago. Many of the South Chicago men who would fight in Vietnam had family members who served in World War II, which qualified them for the G.I. Bill, allowing them to more easily get an education or buy a home. Many people in the community had steady middle-class jobs, often union jobs at the steel mills, such as U.S. Steel or the former Wisconsin, Interlake, or Republic steel companies.

“It was very much a middle-class community,” U.S. Army veteran Ray Arias said. “Sometimes I think that concept gets lost because if they think you’re from a steel mill background…you might be a laborer or something and not make a lot of money, but the trades paid very well.”

Many families lived in multigenerational homes and attended church every Sunday. In 1923, an old army barracks building was brought to the Southeast Side to serve as Chicago’s first Mexican-American church, Our Lady of Guadalupe. Over the next few years, the community raised money to build a church at 91st Street and Brandon Avenue. The church was essential to the families in the community.

“They had a good congregation every Sunday,” Luna said. “Everybody had an Our Lady of Guadalupe painting or statue in the house. So it was always part of…their whole religious character.”

Alfonso Padilla was 14 years old when he emigrated from Mexico to Chicago. His father worked in the steel mills, and the family of seven never missed church on Sundays.

“My mom and dad wanted to come here because this is the land of opportunity, the land where you can feel free,” Padilla told Chicago Stories. He said it was a very difficult adjustment since he was not used to the cold and didn’t speak much English. With everything that was new, Our Lady of Guadalupe felt familiar and safe.

“It was a special place because they had priests that said mass in Spanish,” he said.

U.S. Marine Corps veteran Angel Rosario said life revolved around going to church every Sunday.

“It was a must,” he said. “We celebrated weddings there, baptisms, everything related to religion…My mom always insisted that we go to church.”

The neighborhood church also served as a center of faith and support as many young men in the neighborhood went off to war.

Following in Family Footsteps and Going to War

Many of the men from South Chicago who served in Vietnam had fathers or uncles who had served in World War II or the Korean War. Bill Luna said that patriotism was already embedded in those families, so it was “only natural” for the sons to follow in those footsteps.

“Mexican Americans have always been seen as foreigners, even up to this day. And they have been here for generations in this country…they were always tested to prove their loyalty and their patriotism to this country.”— Bill Luna

No one knows exactly how many Latino soldiers served in Vietnam, in part because the military didn’t keep track. Some reports suggest that they represented a disproportionate number of deaths in Vietnam compared to their share of the American population. This would hold true for the parishioners at Our Lady of Guadalupe.

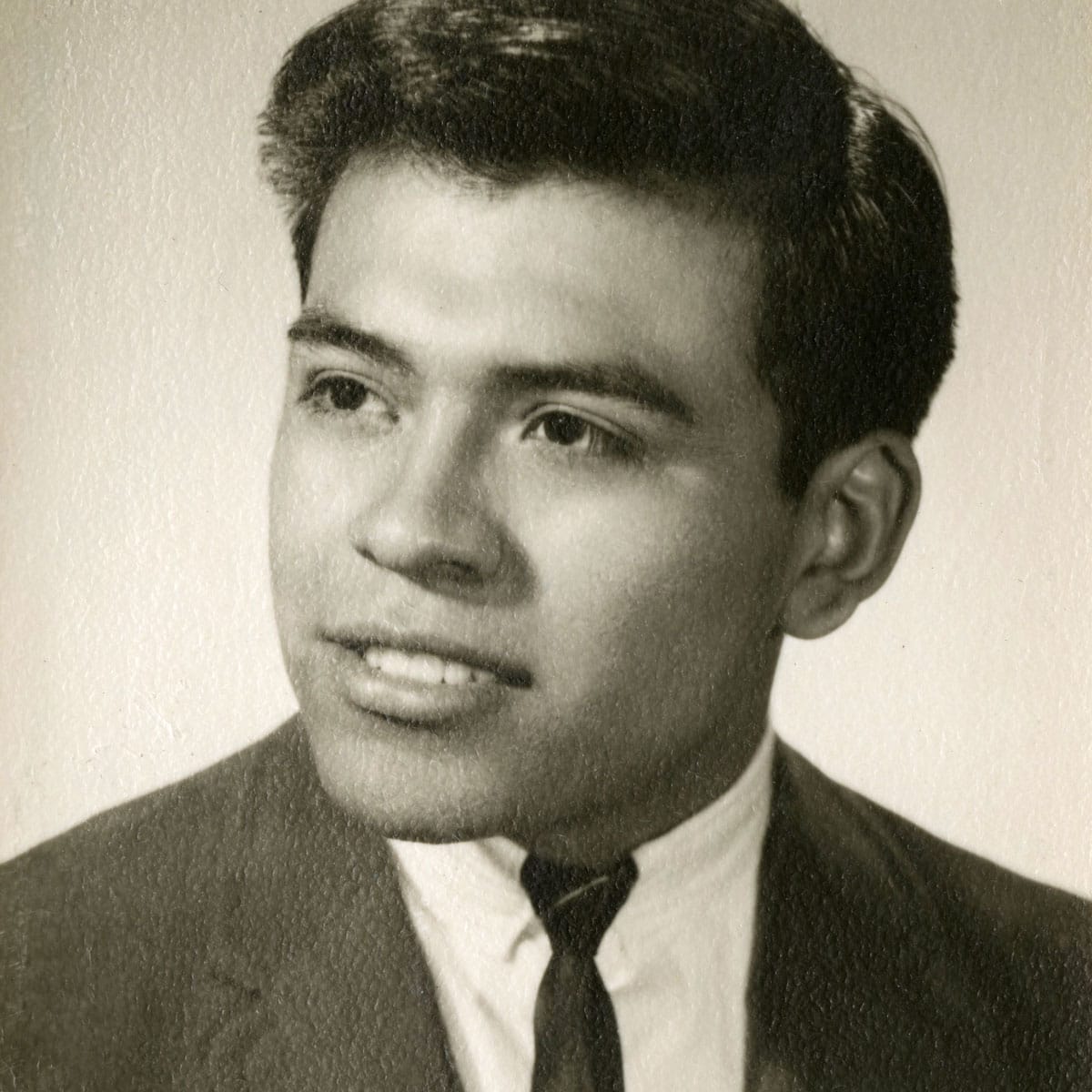

Alfonso Padilla never served in Vietnam, but his younger brother, Thomas, did. Alfonso decided to enlist in the army, but had to convince his mother to sign a form since he was a few months shy of his 18th birthday.

“I just wanted to explore the world…to become a better person,” Alfonso Padilla told Chicago Stories. Thomas had a “kind heart” and wanted to be like Alfonso.

“Tom was a good person. He’ll give you the shirt off his back,” said John Paredes, a friend of the Padillas who also served in the Marines. “He was quiet, and he always wanted to join the army because he wanted to be like his brother.”

So when Thomas got his draft letter, his mother took him to Mexico for a vacation.

“She heard about what was happening and all the body bags that would come back,” Alfonso said. She said he could stay in Mexico to avoid the draft. But Thomas wanted to serve in Vietnam.

“He said to my mom, ‘Mom, all my friends are going. You know how I would feel if I go to Mexico and stay there? I would feel like a coward,’” Alfonso said.

Thomas was deployed a few months later and served as a machine gunner. Before he left, Alfonso had given him advice on how to do well in the service. Thomas was later wounded when he stepped on a booby trap, but he was put back in action. Thomas told Alfonso about the wound, but not his parents, because he didn’t want them to worry.

Like the Padilla brothers, Angel Rosario enlisted as a matter of family pride. He had uncles that served in World War II and the Korean War and a cousin who was wounded in Vietnam before Rosario was old enough to go himself. He was working for powerful Alderman Ed Vrdolyak when he enlisted in the Marine Corps.

When he told his mother, “She didn’t say a word. She went into her room and she cried,” Rosario told Chicago Stories. Training was brutal, but he said he felt prepared as he arrived in Vietnam to serve as a radio operator. Like many of the South Chicago men who would return from Vietnam, Rosario’s experiences in the war proved to be life-altering.

Rosario told Chicago Stories about one story in particular that shaped his experience of the war. Rosario shared a tent with a friend and fellow Marine who owned an item considered a luxury during deployment: an air mattress. When his friend was out on a shift, Rosario got to use the mattress. One night, when his friend returned and got back on his mattress, a round came in. His friend’s body was hit by the shrapnel, and he died in Rosario’s arms.

“He just stayed there, [and I held] him in my arms, rocking him,” Rosario recounted. He escaped that incident unscathed. “I walked away, and I always wondered why.”

“There’s so many… different ways of dying that I couldn't ever believe was possible, but it is,” he said. Rosario would later deal with the trauma of war, but many of his neighbors never returned to South Chicago.

The Fallen Soldiers of Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church

It is believed that Our Lady of Guadalupe suffered more than any other parish in the country. Twelve young men did not return home. Five were killed within five months of each other. One family would comfort another not long after they lost their own son.

Gloria Chavez-Gomez was a member of one of those families. She was still in high school when her older brother, Antonio, went into the service like her other brothers. She said Antonio was brilliant and wanted to be an architect. He had just turned 20 when he was killed in Vietnam in 1967.

“I remember the two officers coming and knocking on the door, and all I saw was my mother. She said, ‘No, no!’ and she fainted,” Chavez-Gomez told Chicago Stories. After she got the news, she went to Our Lady of Guadalupe to light a candle.

“You light the candle, and you pray and say, ‘Why, God? Why?’ But you don't get your answers,” she said. They played “Taps” at Antonio’s funeral. She still keeps a photo of him on her mantel to this day. She said her brother’s death ultimately strengthened her faith.

But Antonio’s death wasn’t the only one that hit close to home. Michael Miranda, another young man from Our Lady of Guadalupe and godchild of Chavez-Gomez’s mother, was also killed in action. Chavez-Gomez has his dog tags. She said he was a lot like Antonio.

“That’s the sad part. You knew them. And they were here. You spoke to them, you played with them, you ate with them here. All of a sudden, boom, they’re gone.”— Gloria Chavez-Gomez

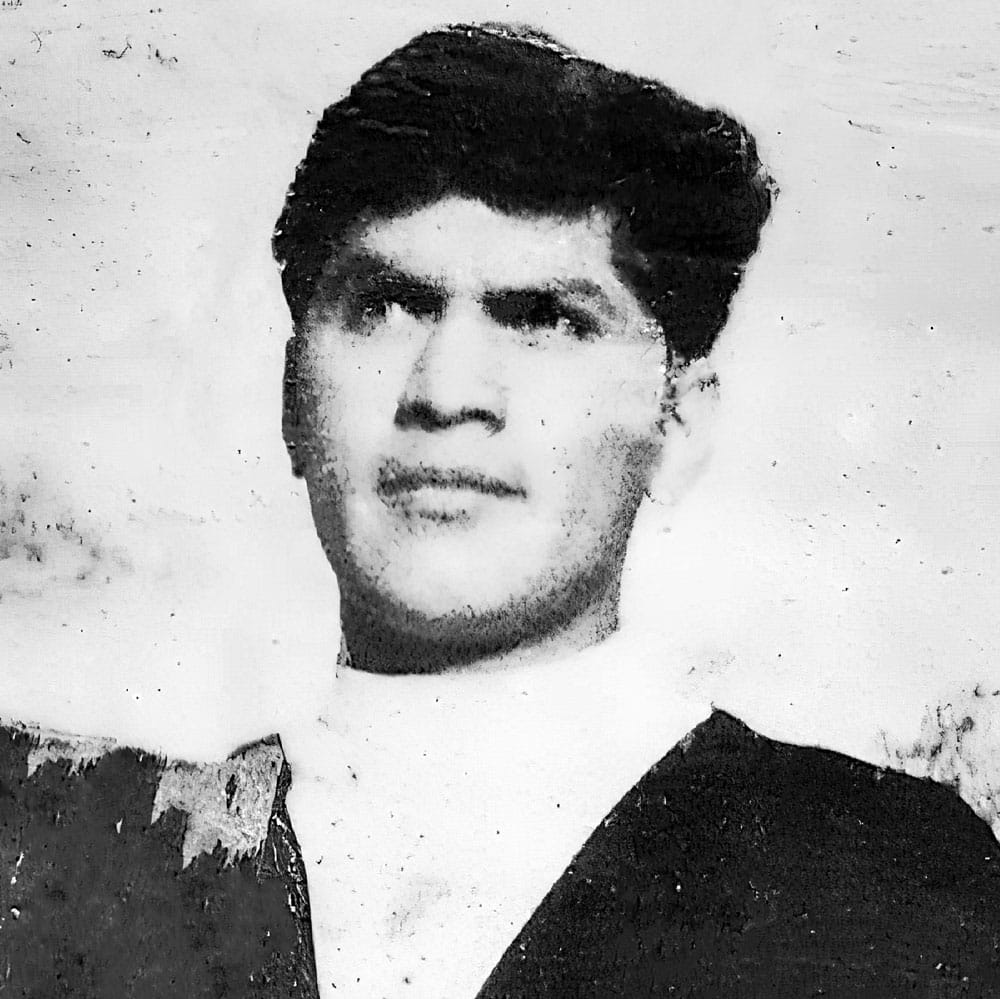

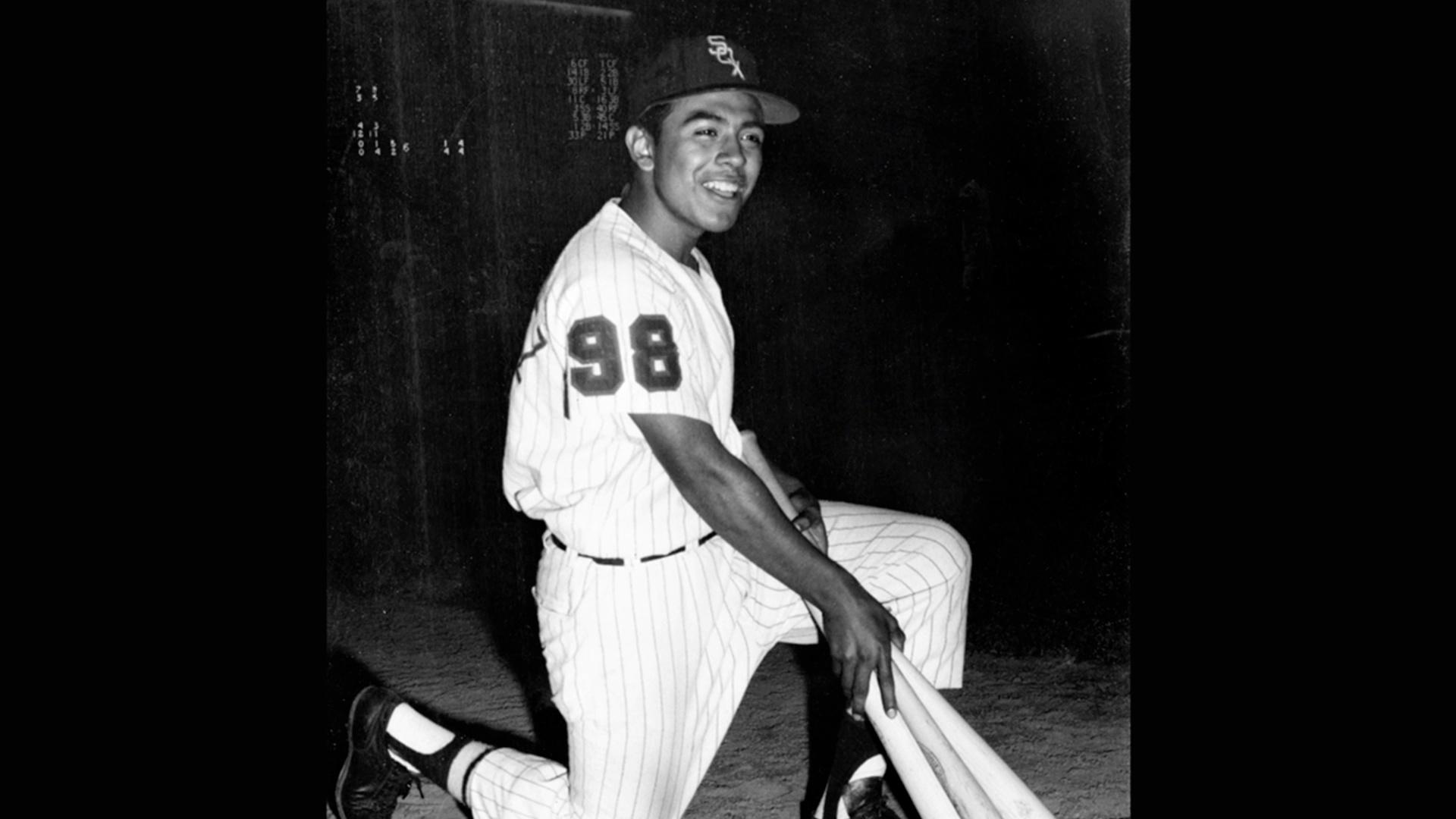

The family of Edward “Eddy” Cervantez also got a knock on the door from uniformed soldiers. Cervantez was the son of a steel worker and the oldest boy of 17 children. Their family went to Our Lady of Guadalupe every Sunday. Cervantez was beloved in his community and had once been chosen as a bat boy for the Chicago White Sox.

“I remember him coming home from work and talking to my dad at the kitchen table about going [to Vietnam]. He wanted to go,” Joe Cervantez, Eddy’s brother, told Chicago Stories. Eddy was killed in 1968.

“They knocked on the door, and they informed my mother that he had passed,” Joe Cervantez said. As soon as she saw them, “She knew right away,” Cervantez said. When Antonio Chavez had died, Joe said his family had comforted the Chavez family.

“My mom went to his house to console [Antonio’s mother], and when they found out, they came and did the same,” he said. It took a double room at the funeral home to host the entire Cervantez family and all of Eddy’s friends. Representatives from the White Sox attended, too.

The 12 Fallen Soldiers of Our Lady of Guadalupe

Edward Cervantez

Antonio G. Chavez

Leopoldo A. Lopez Jr.

Joseph A. Lozano

Michael S. Miranda

Raymond Ordoñez

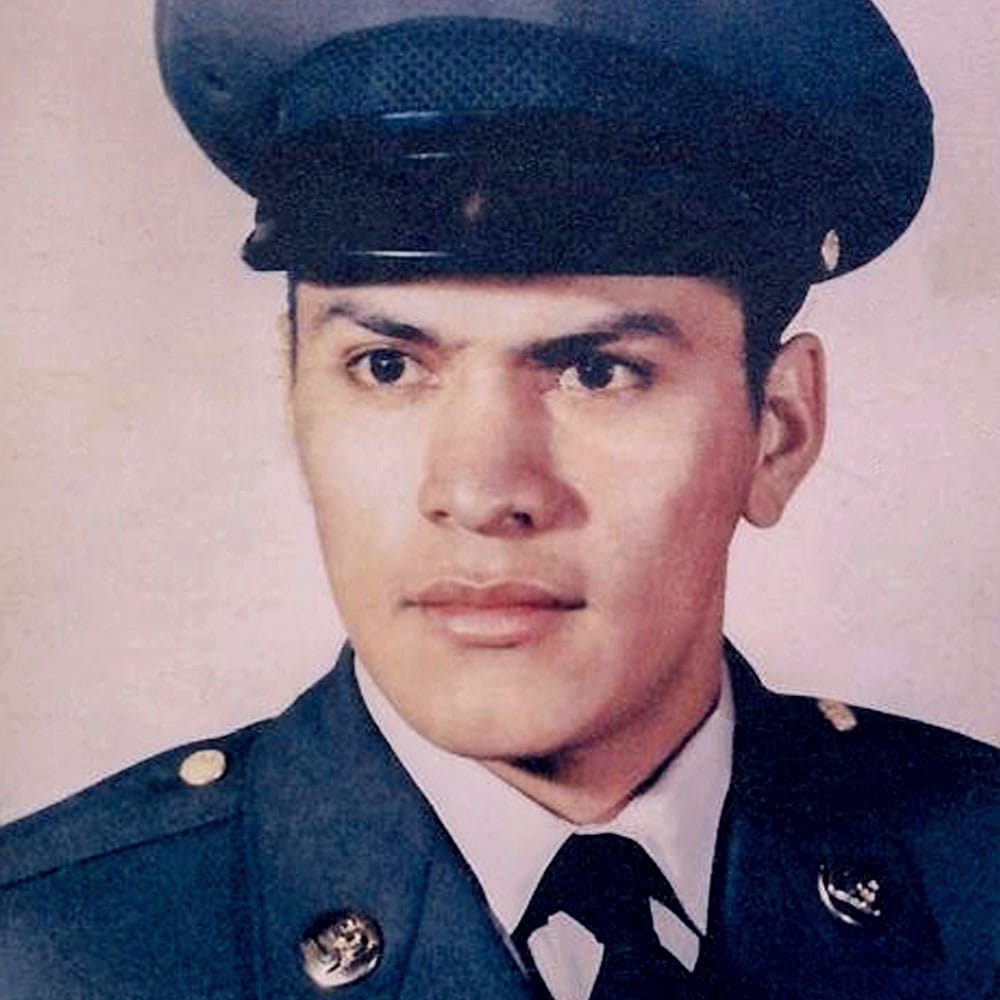

Thomas R. Padilla

Joseph A. Quiroz

Dennis J. Rodriguez

Peter Rodriguez

Alfred Urdiales Jr.

Charles Urdiales Jr.

Alfonso Padilla also lost his brother, Thomas. In late March 1970, Alfonso was opening up work on a snowy morning when his sister called and told him that military escorts had arrived at the house to inform them that Thomas had died.

“I ran all through that snow [to go home],” he said. “We knew he was in danger, but we didn’t expect it.”

Alfonso said his mother was not comforted by a medal Thomas had been awarded.

“She says, ‘Maybe this wouldn’t have happened if we stayed in Mexico,’” he said. “She told them, ‘Who cares about a medal? All I want is my son.’”

Thomas’s funeral was packed, Alfonso said. He said his brother had a lot of friends, had good character, and left behind a girlfriend. Thomas’s death was hard on the family, but his mother turned to Our Lady of Guadalupe.

“That’s the only thing that kept her going – being close to God,” Alfonso said.

Our Lady of Guadalupe was an important resource for the grieving families. Bishop Plácido Rodriguez had just gotten his first assignment as an associate pastor at the church after he was ordained. His own brother had died in Vietnam, so he shared something with the families he visited.

“It was easy to share with them because we had the same loss,” Rodriguez told Chicago Stories. “Our faith was shaken all the time.”

Remembering the Scars of the War

While the families of the 12 soldiers grieved, many other young South Chicago men returned from war with their own burdens.

Upon his return to the United States, Angel Rosario said he was met with protestors throwing eggs and trash at the windows of his bus, calling him and other soldiers “baby killers.” He struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“For a long time, I didn’t talk about it at all,” Rosario told Chicago Stories. “It was a subject that most people didn't want to approach. How are we supposed to talk about something that we didn’t really fully understand ourselves?” Rosario remembers going to confession after returning from Vietnam. The priest told him his penance was to read the entire Bible. “I’m thinking, damn, is it that bad?” he said.

U.S. Army veteran Joseph Sanchez was also from South Chicago and struggled with PTSD. He had two army friends who died by suicide. He recalled attending a seminar that discussed 12 potential signs of PTSD. “I had eight,” he said. “I carry a scar. Every veteran carries a scar.”

In a parking lot across the street from Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church, a reddish-brown stone memorial lists the names of the 12 soldiers who died in Vietnam. It reads, “We owe so much to so few.” Behind the stone is a colorful mural that features paintings of the 12 men. Most were in their early 20s when they were killed. The Urdiales family lost two sons – Alfred and Charles.

Bishop Rodriguez said it was unique for a church to have its own memorial to fallen soldiers, especially since it was established long before the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C.

“It was unusual because it shows that we do have community, that we are family-oriented, that we have a sense of community that is unique,” Rodriguez said. “It not only activates the memory and brings the history of the Vietnam War, but it also brings the memory that our community is good, that our community is looking for healing, that our community sticks together and is able then to contribute to society, no matter what.”

Gloria Chavez-Gomez said it was sad to see just how many young men from the parish were on the memorial when it was first dedicated in 1970. Alfonso Padilla said when he went to the first Memorial Day ceremony at the memorial to honor his brother Thomas, he saw a lot of pride from the soldiers’ families.

“I cried at the time, maybe because I didn’t spend enough time with my brother. Maybe I could have told him something else that would have helped him,” Padilla said.

Bill Luna thinks it’s one of the most “outstanding memorials in the city.”

“When you see it and you see the pictures of all those 12 kids on the wall there, it really tugs at your heartstrings…If you…ask the people in Chicago about the memorial, very few people…know [about] it at all.”— Bill Luna

Joe Cervantez said the fact that people in the community still visit the site on Memorial Day and Veterans Day shows that so many people still respect the sacrifices the families and their sons made. Cervantez goes every year.

“I’ll do it until I can’t walk anymore,” Cervantez said, “and then I’ll go in the wheelchair.”