Dealing with unsafe working conditions and unhealthy living conditions in the Back of the Yards neighborhood, the workers of the Union Stockyards found an unlikely advocate in a woman who became known as the “The Garbage Lady” and the “godmother” of environmental justice. From the late-nineteenth century into the early-twentieth, a woman from a privileged background named Mary McDowell led a crusade for environmental justice that would improve the lives of the immigrants among whom she lived.

Born in 1854, Mary McDowell was originally from Cincinnati, but moved to Chicago with her family as a child. As an adult, McDowell got involved with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union in Evanston, working with reformer and suffragist Frances Willard. McDowell also began working with Jane Addams’s Hull House, teaching kindergarten there.

In 1894, McDowell used her experience at Hull House to help establish the University of Chicago Settlement House in the Back of the Yards neighborhood. According to the Social Welfare History Project, Jane Addams and University of Chicago faculty selected McDowell to lead the settlement house that would serve as a kind of “living laboratory” for understanding the needs of the immigrant population living near the stockyards. For the next several decades, McDowell was the “head resident,” living among the people she served.

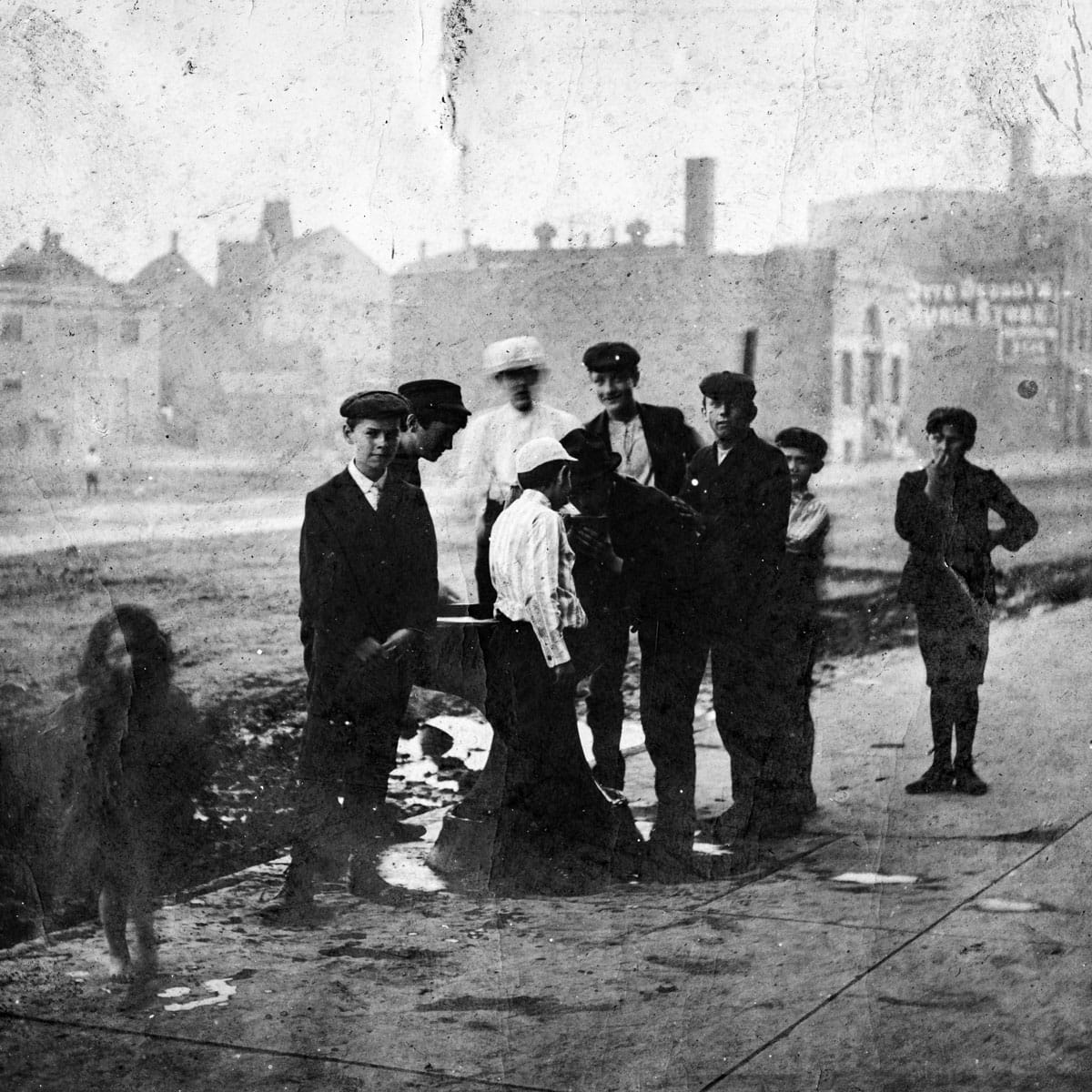

At the end of the nineteenth century, the Union Stockyards often employed Irish, German, Polish, and other European immigrant workers. In addition to unsafe working conditions in the packinghouses, workers’ living conditions were also inadequate. Their families routinely experienced poverty, pollution, and illness.

McDowell’s settlement house sought to alleviate some of those issues. Her work originally started out above a small feed store on Ashland Avenue. Eventually, she worked out of a building on Gross Avenue (later renamed McDowell Avenue) between 46th and 47th streets. She first started offering kindergarten classes, but over the next few years, the programs grew to include women’s clubs, youth groups, English classes, and a play area for children, according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago.

Sanitation was a neighborhood issue that McDowell would work on for decades. Parts of Back of the Yards essentially became large garbage-dump sites. Historian Dominic Pacyga told Chicago Stories that the smell and sanitation concerns from the dump sites were a major problem in the neighborhood. Children sometimes got into them to search for things. Diseases spread more easily.

“These dumps were huge,” Pacyga said. “Mary McDowell…was known as ‘The Garbage Lady’ because she fought against the dumps.”

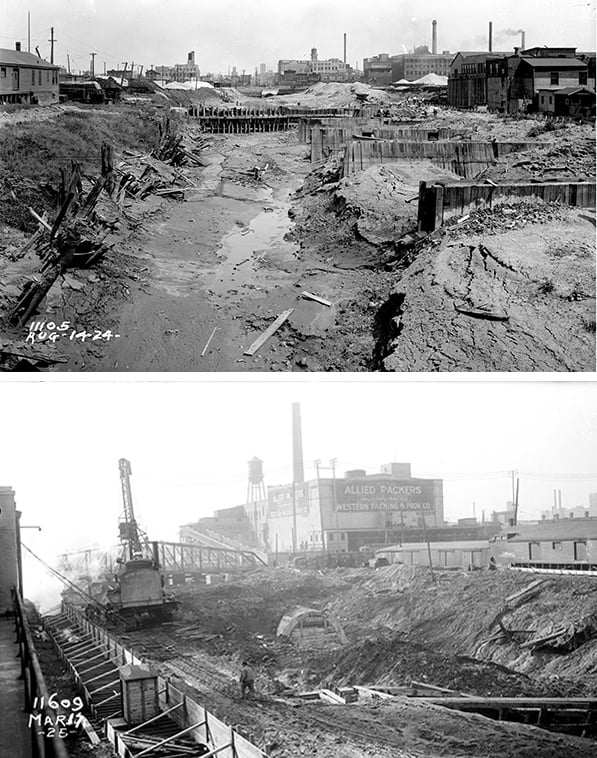

The nearby “Bubbly Creek” – the South Fork of the South Branch of the Chicago River – was also a major health concern. The slaughterhouses dumped raw sewage, animal carcasses, chemicals, and other items that allowed methane to build up in the creek, causing it to sometimes literally bubble. Parts of the creek were so overrun with waste that it was partially solid in places. As Upton Sinclair wrote in his 1906 novel The Jungle, “[C]hickens walk about on it…and many times an unwary stranger has started to stroll across and vanished temporarily.” For decades, McDowell led the call to have Bubbly Creek cleaned up.

Environmental research scientist Sylvia Washington told Chicago Stories that during McDowell’s time, Back of the Yards families were experiencing the same environmental justice issues that many communities in Chicago still deal with today – problems created by the nearby industries, not the people themselves.

“This group of people is suffering more because of environmental conditions that [are] not being produced by them,” Washington said. “Mary McDowell understood very deeply that the disease and the death and the destruction and disruption of immigrant lives in their neighborhood was tied to their environment. And she wanted to clean up that environment because she saw its impact on immigrant lives, immigrant bodies.”

McDowell studied sanitary engineering in Europe to better understand the issue and how to solve it. Though she may not have been allowed to become an engineer, vote, or run for office herself, McDowell used her position in society as an educated woman to work for those with less power.

“She exercised her power in the way that she could. Immigrant women could not do that…but a woman of privilege could do that,” Washington said. “How many women at that time could go off to Europe and be trained in sanitary engineering?”

Washington said she considers McDowell to be the “godmother” of what became the environmental justice movement. In more than three decades of living in the Back of the Yards community, McDowell accomplished a lot. She successfully got the garbage dumps closed down, and she also helped officials implement a city-wide garbage disposal system. Her efforts eventually got the city to fill in a portion of the polluted Bubbly Creek, too. Her settlement house served countless immigrants and, later, Blacks coming to Chicago during the first wave of the Great Migration. McDowell’s work also led to ten new neighborhood parks – including Davis Square Park in Back of the Yards – to give workers and crowded neighborhoods much-needed green space.

“I think that the beauty of the story is [that] she decided to take her power and get the knowledge,” Washington said. “She knew that she had a voice at the table, she knew that it wasn't equal to the men at the table, but it was sufficient enough to motivate them to make change.”