Chicago was famously dubbed “Hog Butcher for the World” by Carl Sandburg in his iconic poem “Chicago.” The city was the center of America’s meatpacking industry for roughly a century, transforming the way livestock were sold, processed, transported, and eaten. Industrialist tycoons such as Philip Armour and Gustavus Swift created and then dominated an industry that changed Americans’ relationship to meat – and squeezed out massive profits at the same time. A century and a half after they first began processing “everything but the squeal” in Chicago, many of their abuses – an indifference to workers, health, the environment, or smaller business – are once again a part of the industry.

A Dangerous Industry

Some of the earliest outbreaks of the COVID-19 pandemic were concentrated in meatpacking plants throughout the country. Workplace safety complaints from meatpackers to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) skyrocketed in the first four months of the pandemic, and by September 8, 2021, at least 298 meatpackers had died of COVID.

Meatpackers were deemed “essential workers,” and President Donald Trump issued an executive order to keep the facilities open in late April 2020. But their pay was low – one worker at a Mountaire poultry plant in Delaware told The New Yorker that she was paid about $13 an hour before the pandemic and given a hazard-pay increase of a dollar an hour only through June, 2020 – 44 percent less than the national average for manufacturing jobs. Roughly one in five meatpacking workers are food stamp recipients, according to The Guardian’s parsing of U.S. census microdata.

The dangers of working in the meatpacking industry – and the larger abuses wrapped up in the industry – long predate the pandemic. They stretch back all the way to the creation of industrial meatpacking in the second half of the nineteenth century, when Chicago was the center of the industry and tycoons such as Philip Armour and Gustavus Swift squeezed massive profits out of processing meat.

The meatpacking industry “is a greater power than in the history of men has been exercised by king, emperor, or irresponsible oligarchy,” wrote the muckraker Charles Edward Russell in 1905.

Armour, Swift, and other Chicago businessmen refined industrial meatpacking into a mercilessly efficient, devastatingly brutal machine indifferent to workers, health, environmental concerns, or competition. “It was truly a social transformation and technological transformation,” the environmental historian Sylvia Washington told Chicago Stories. “Everything from the agriculture to the natural environment to public health to economies.”

“The story of meatpacking in Chicago is a story of American capitalism,” historian Dominic Pacyga told Chicago Stories. Technological innovations were made, monopolies were created, labor clashed with tycoons, economies were transformed, environments destroyed, and the American consumer’s relationship to food was forever changed. And Chicago was its capital.

New Inventions, Mass Production, and Cheaper Meat

Due to its central location, position as a railroad hub, and proximity to Midwestern farms, Chicago was ideally situated to become America’s meatpacking capital, especially during the Civil War, when the Union Army needed food, and blockades disrupted old trade routes.

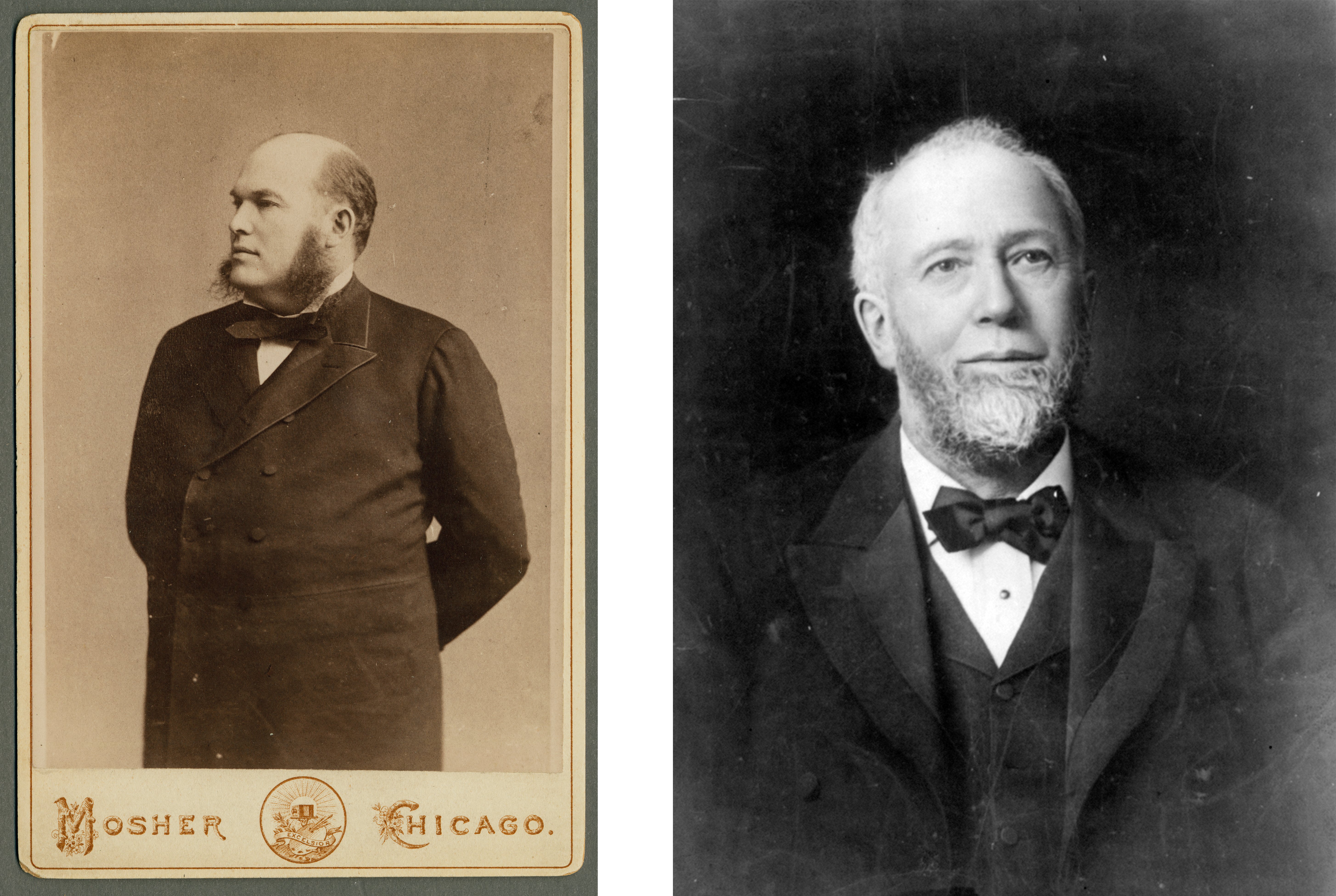

One of the people who helped Chicago dominate meatpacking was Philip Armour. He had amassed a fortune by investing money earned selling supplies to Western gold miners into pork futures in Milwaukee.

“Market manipulation is very important to a guy like Phil Armour,” author Maureen Ogle told Chicago Stories. Soon, “Armour realized that Chicago was going to be the big gold mine for anyone who was interested in profiting from Americans’ passion for meat.”

He had a centralized location for his business: on Christmas Day, 1865, several stockyards and railroads, led in part by Nelson Morris, had consolidated to form the Union Stockyards. Located four miles south of downtown on a drained swamp, the stockyards eventually encompassed a square mile of pens and slaughterhouses where livestock were shipped from across the country to be sold and shipped to other parts of the country. Farmers had to pay to have their animals fed and watered while at the stockyards.

The stockyards transformed Americans’ relationship to meat. Before mass production, most meat came from local farms and was butchered either by the farmer himself or at a nearby market. But now, it could originate halfway across the country and arrive at the customer as a packaged cut of meat. The consumer had been divorced from the origin of the product — a radical change that still describes the way most people in this country eat today, despite efforts to “eat local.”

A new technological development enabled this transformation: the refrigerated train car. Gustavus Swift realized that killing and butchering livestock in Chicago and then sending the cuts of meat out across the country was cheaper than shipping live animals, so he developed a system of icing stations along railroads to keep the refrigerated cars and their contents cool.

When the meat made it to market, the meatpacking bosses used cutthroat tactics on traditional butchers around the country. Demanding that butchers sell their meat or else go bankrupt, meat industry leaders opened their own shops and sold at fire-sale prices until the recalcitrant butchers went out of business.

“A small handful of people reinvented the system of meat delivery,” Ogle said. “They streamlined it, industrialized it, automated it.” Soon, the Chicago companies controlled the industry, as well as much of the infrastructure supporting it.

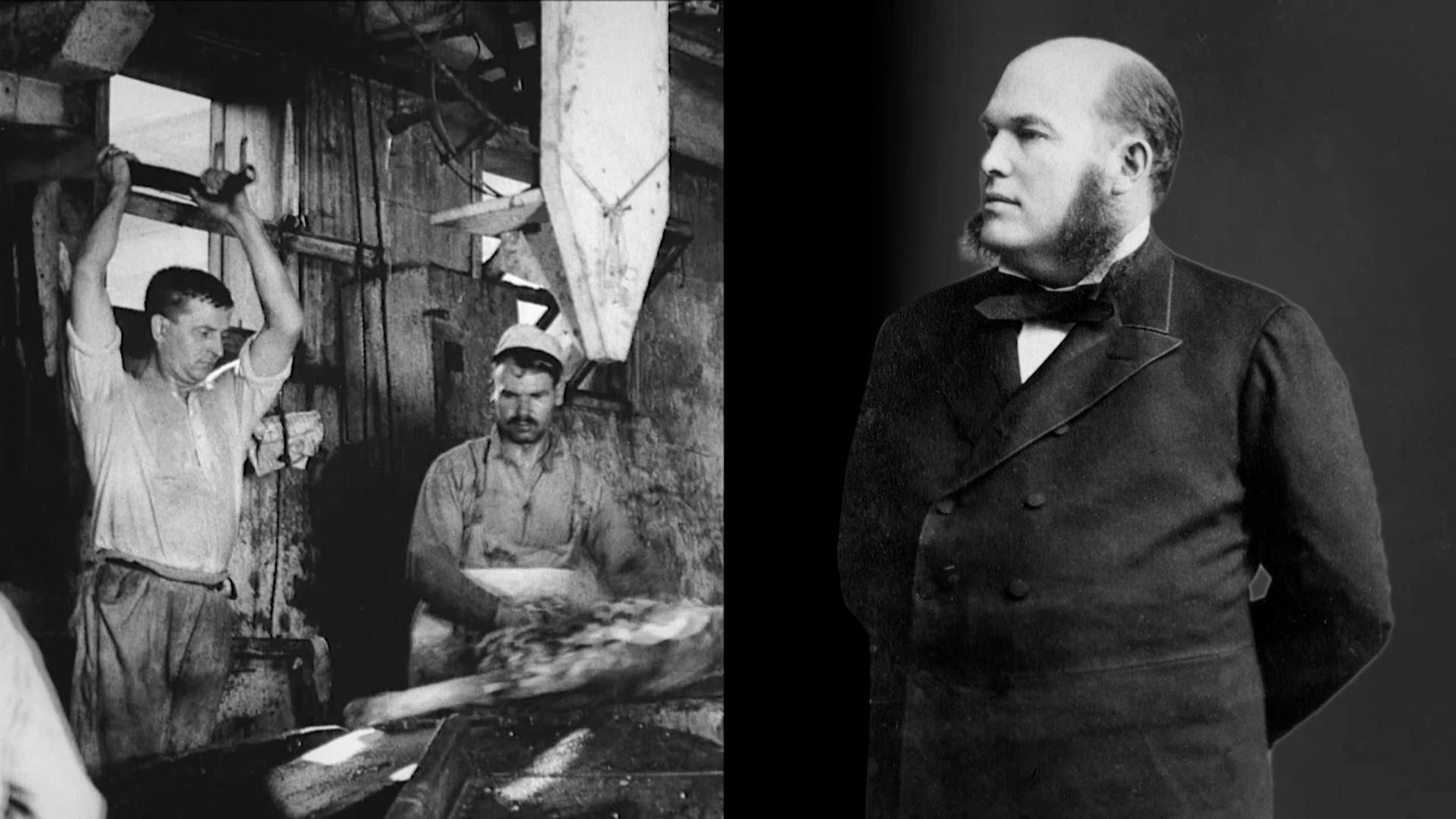

Meat also became amazingly cheap. By developing labor divisions in the breaking down of an animal – a sort of “de-assembly line” that later influenced Henry Ford – Armour maximized efficiency, reducing exponentially the time it took to dress livestock, from eight to ten hours down to 34 minutes for a single steer. And no part of the animal was wasted, thus further increasing profits. Gravy, chili, hot dogs, chitterlings, dog chews, violin strings, paint brushes, leather, make-up, fertilizer, pharmaceuticals: different parts of the animals went into all of them.

“There’s no way to overestimate the importance of byproducts in terms of subsidizing the low cost of meat for Americans in the late nineteenth century,” Ogle said.

The Struggles of the Workers

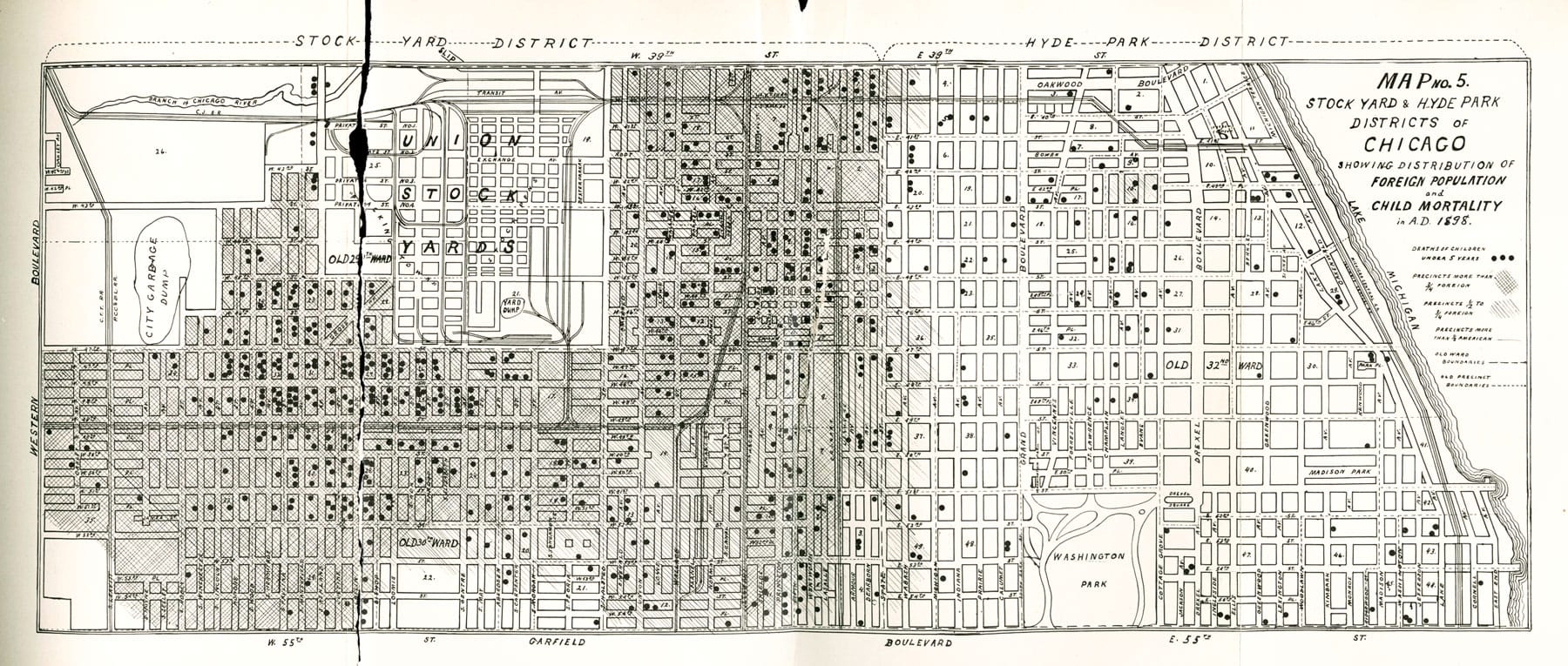

That low cost had an effect on the workers laboring at the stockyards. Just as today many meatpackers are immigrants – including refugees from El Salvador, Somalia, Sudan, Myanmar, and other places – so they were then. Whereas many workers today are Black or Latino, in the late nineteenth century they were primarily European: Polish, Lithuanian, Bohemian, Italian.

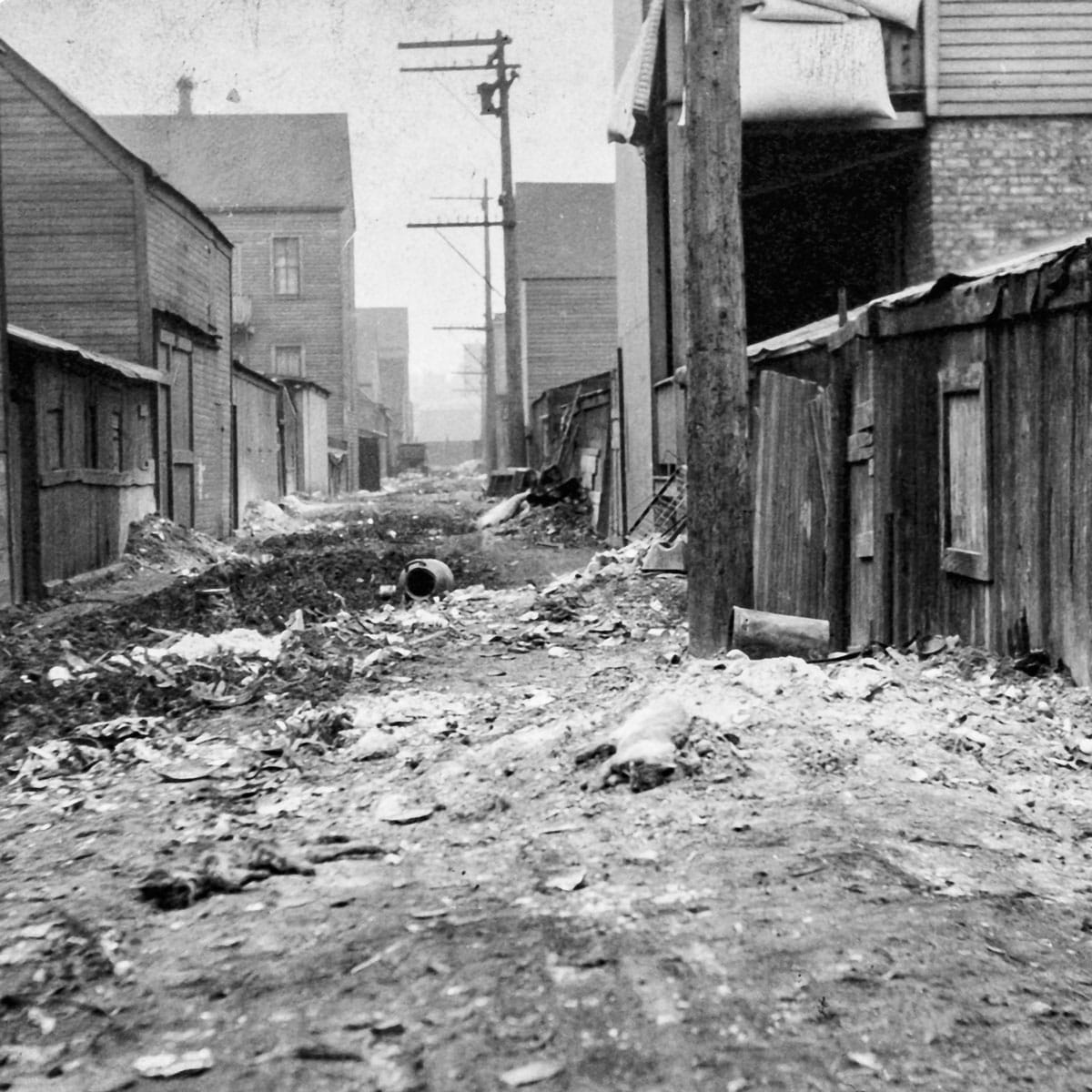

Many of the workers lived in the neighboring Back of the Yards slum, which suffered from the stockyards’ waste with both a dump and the stagnant Bubbly Creek section of the river. Working conditions in the stockyards were also rough. Workers were told to just use a corner of the room as the bathroom. Workers who processed bones for fertilizer contracted lung disease; tanners developed sores and cuts on their fingers from working with chemicals without gloves. And then there were the dangers of amputation and other injuries, still common today.

Attempts to unionize in the early days of the meatpacking industry had been crushed, with Armour threatening to leave Chicago with all the jobs his businesses provided. On May 1, 1886, the Knights of Labor organized the stockyards to join a nationwide strike for an eight-hour workday.

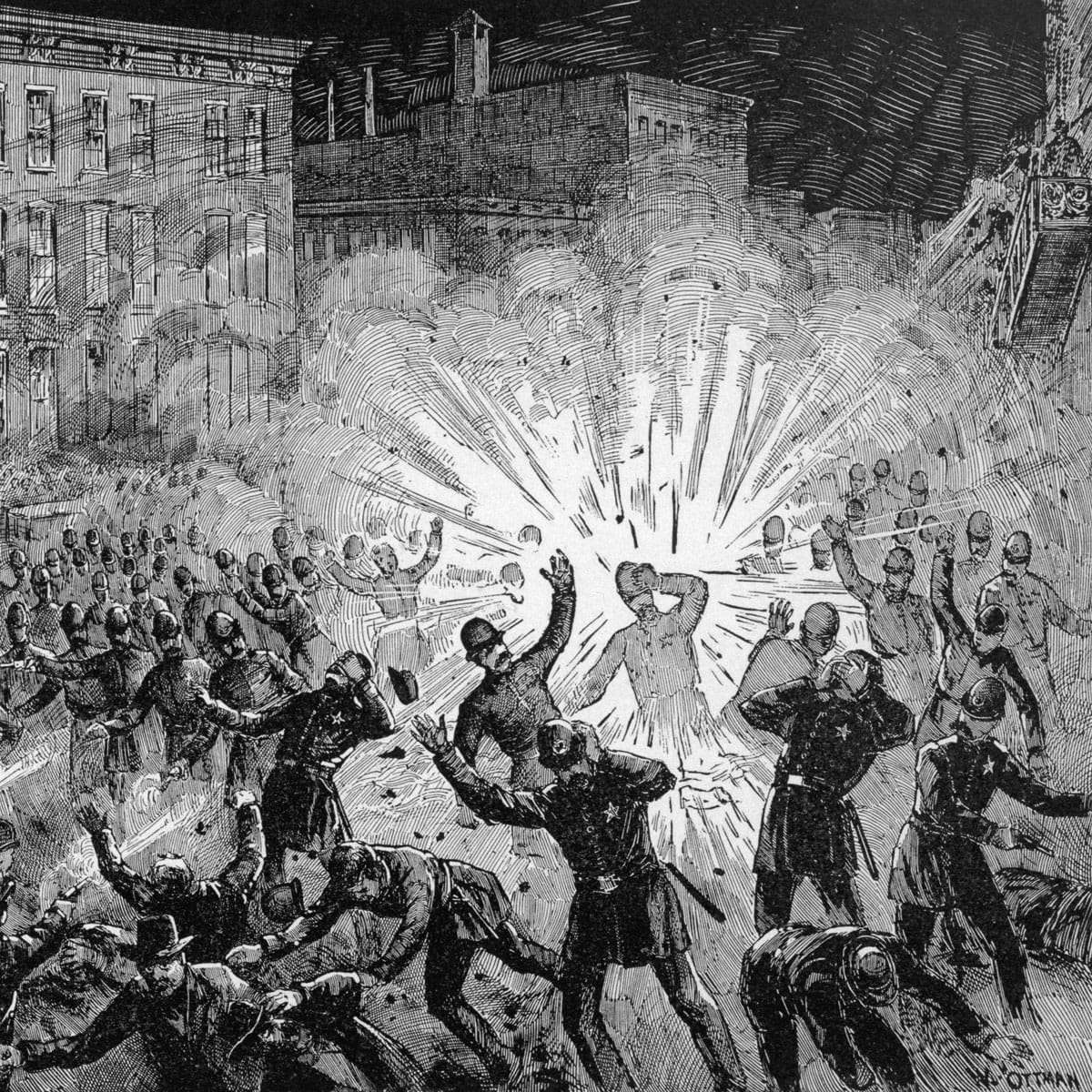

(3) An illustration of the Haymarket Affair Image: Public Domain

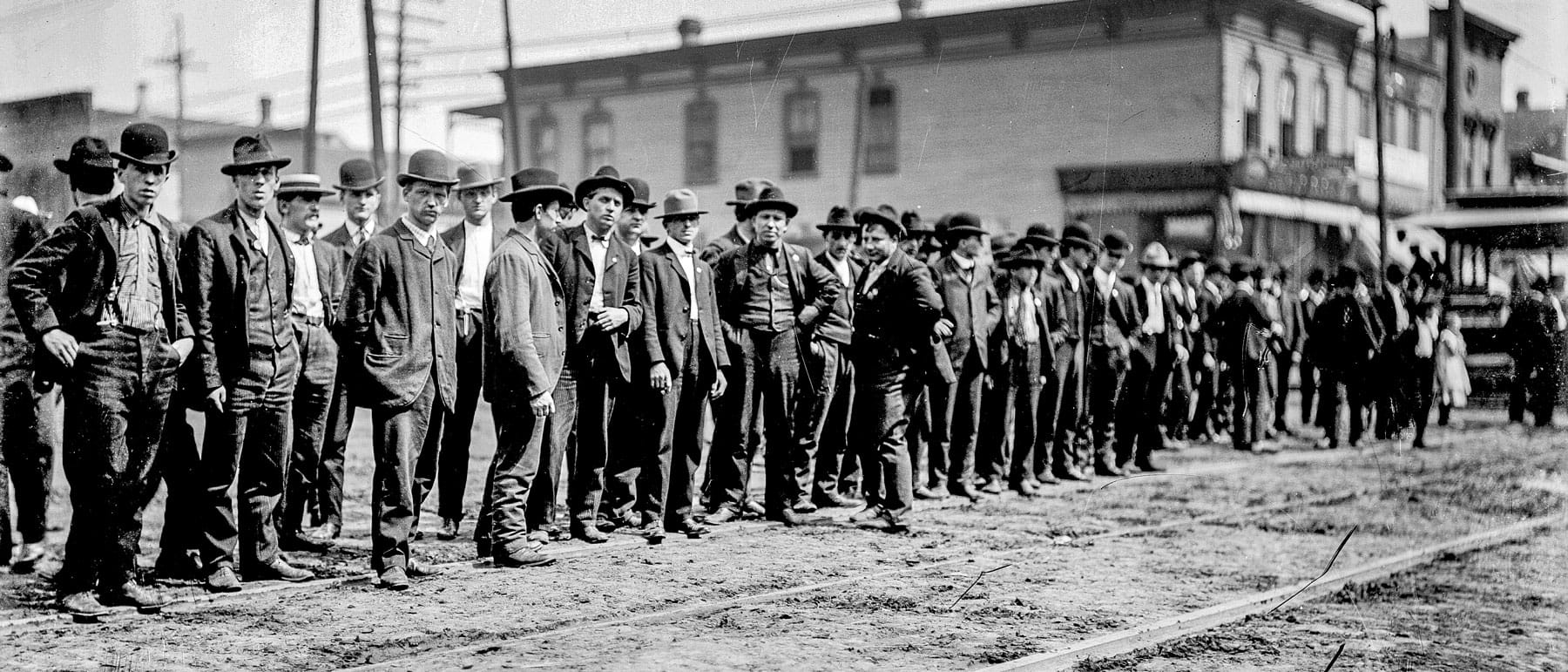

(4) Stockyards workers went on strike in 1904. Image: DN-0000909, Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum

The strike at first seemed successful, but then came the Haymarket Affair. Someone threw a bomb at police during an otherwise peaceful gathering of anarchists, leading the police to retaliate with gunfire. The death of eight officers and several civilians – and the resulting chaos – turned public opinion against labor unions, as did the tycoons’ argument that unionization would lead to higher meat prices for the consumer.

After a strike, firings, the arrival of Blacks from the South to replace workers, and intimidation by the infamous Pinkerton Detective Agency, workers returned to 10-hour days, and the labor movement in Chicago was halted for a time. Another large strike in 1904 during which some 50,000 meatpacking workers walked off their jobs was met with near-total defeat.

By the 1890s, Armour was one of the wealthiest people in Chicago, and his company was the largest industrial employer in the city. One in four Chicagoans depended on the industry for employment.

The industry itself had also become a spectacle. By the turn of the century, 500,000 people were visiting the stockyards every year to see the marvel of their workings.

Armour did engage in philanthropy. An Armour Mission existed, thanks to Armour and his brother’s charity, to provide Sunday school for children. One million dollars from Armour founded the Armour Institute, which eventually became the Illinois Institute of Technology.

“There’s lots of buildings that have the names of industrialists on them who did absolutely terrible things to human beings,” labor historian Robert Bruno told Chicago Stories. “And then you use the wealth that they created from that exploitation to alter their public perception.”

But a backlash was on the way. Armour’s business survived testifying before a Congressional committee investigating the meat industry after a cattle bust in the West hurt ranchers, butchers, and railroads. He died in 1901; Swift died the following year.

In 1906, Upton Sinclair published The Jungle, which detailed the degradations and disgusting conditions of the stockyards. Armour’s son tried to kill the book before publication, but it instead became a bestseller and inspired a national movement for food safety that culminated in the passage of both the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Federal Meat Inspection Act, even though Sinclair wanted to call attention to the plight of workers rather than health standards.

Another federal investigation during World War I led to the passage of the Packers and Stockyards Act in 1921, which further curtailed the industry’s unchecked power by forcing meatpackers to limit their business only to meat processing, not transportation, sales, or any other aspect of their former monopoly. The Congress of Industrial Organizations organized tens of thousands of workers in the stockyards in the 1930s, leading to higher pay and better hours.

By the mid-twentieth century, the construction of a national highway system and the advent of refrigerated trucks had begun to take business away from the stockyards. Centralization of the meatpacking industry was no longer essential. Armour and Swift shuttered their Chicago operations in 1959, and the Union Stockyards closed for good on July 30, 1971. OSHA was created the same year.

Echoes of the Union Stockyards in the Meatpacking Industry Today

Though the industry itself is no longer centralized in big cities, meatpacking has once again in the past several decades begun to resemble the notorious industry over which Armour and Swift presided.

“We’re very much back in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle,” a former head of OSHA told The New Yorker.

Since the 1970s, meatpacking has moved to rural areas. Whereas nearly 80,000 meatpacking workers in the Midwest worked in cities and fewer than 20,000 worked in rural areas, in 2007 there were more rural workers than urban. As deregulation took place in the 1980s and antitrust enforcement declined, companies began to consolidate operations as they had in the past.

They once again turned to non-unionized, immigrant workforces. Many meatpacking workers, especially in the poultry industry, are vulnerable, often immigrants or refugees hired on contract. Only 18 percent of meatpacking workers belonged to unions in 2020, down from 90 percent in 1952. Large meatpacking companies often locate their plants in rural areas where they exert inordinate political power as the main economic driver of the region.

The job is still dangerous, too. According to government statistics, meatpacking companies report more severe injuries, often including amputations, than industries people might expect to be more dangerous, such as mining or sawmills. A meat or poultry industry worker lost a body part or was sent to the hospital for in-patient treatment nearly every other day between 2015 and 2018, according to Human Rights Watch.

Meatpacking companies reported the highest rates of repetitive stress injuries of any industry before OSHA stopped collecting such data in 2001. A report in The Atlantic by a writer who worked in a Cargill plant in Dodge City, Kansas, noted that he took up to four ibuprofen tablets a day to ease pain and stiffness in his hand, while many of his coworkers used the opioids oxycodone and hydrocodone as painkillers. A Southern Poverty Law Center survey found that 79 percent of workers said they are not allowed to use the bathroom when they need to.

The industry is also extremely concentrated, as it was in the days of Armour and Swift. Cargill, JBS, Tyson, and National together control 85% of the beef market and 70% of the pork market. The 10 largest poultry companies controlled nearly 80% of the chicken market, and some have been accused of fixing chicken prices and conspiring to hold down workers’ wages, allegations the companies have denied. A court settlement in 2021 required the poultry company Mountaire to pay a total of $205 million for polluting well water with waste from its plant in Millsboro, Delaware, just as the stockyards polluted Bubbly Creek a century earlier.

Large industrial meatpacking companies also continue to keep meat prices so low that smaller, local producers struggle to compete, as Illinois farmer Louis John Slagel told Chicago Stories. “The industrial system really supplies extremely cheap meat products for the average American consumer,” he said. “I can’t compete with the big guys, the big packers. We charge based off the true cost.”

As in so many other areas, the pandemic laid bare problems in the meatpacking industry. As the history of Chicago’s meatpackers show, those problems are nothing new.