Discussion Guide | FIRSTHAND: Segregation

Discussion Guide

Download a PDF of the Discussion Guide

About the Series and Discussion Guide

FIRSTHAND: Segregation tackles one of Chicago’s most enduring facts of life, doing what research studies, facts, and figures about the racial divide in Chicago cannot do: it shows how segregation and its inequities impact everyday life in Chicago. The 15 stories and 6 talks together reveal the social, economic, and political causes and costs of segregation, the promises and perils of integration, the difference between imposed segregation and self-segregation, and the inspiring efforts to dismantle and disrupt the inequities and divisions that flow from segregation.

The purpose of the FIRSTHAND project is to put a human face on issues facing Chicago and bring to life important stories from personal, firsthand perspectives. This discussion guide for FIRSTHAND: Segregation seeks to guide viewers through the experience of watching the stories, encouraging them to dig deeper into the complexities of segregation and reflect on the ways that this series makes more visible – and personal – the structural forces that create and perpetuate it.

The guide’s goal is to create reflection and discussion that can help viewers experience the reality of segregation by connecting with the people who share their stories of this baked-in feature of Chicago and many other American cities. This discussion guide can support community members and organizations, educators, faith community leaders, and policymakers in facilitating conversations about the issues raised in FIRSTHAND: Segregation.

The discussion guide groups the 15 stories into four themes:

Theme One

Segregation’s Costs

Theme Two

Community, Belonging, and Displacement

Theme Three

Integration’s Promises and Perils

Theme Four

Building Bridges Across Communities

Within each theme, the guide provides story-specific discussion questions that encourage viewers to reflect, connect, and act. The guide also provides quick facts and resources to dig deeper and learn more about each theme. In addition, the series includes six expert talks that provide context around the topic of segregation in Chicago. The goal of the guide is to help build successful conversations that engage viewers and inspire further action to help disrupt the cycle of segregation and the inequities that flow from it.

At the end of the discussion guide, you can find tips for setting up your discussion, advice about laying the groundwork for dialogue about sensitive topics, and a timeline to help in your preparations.

Background Information: Causes and Consequences of Residential Segregation

What Is Segregation?

Segregation is a seemingly simple term that is shorthand for lots of different things, and segregation is caused by many different forces, both past and present. Therefore, it’s helpful to break it down and spell it out. The Othering and Belonging Institute has done just that with the Roots of Structural Racism Project. As they explain it:

"Segregation is the separation across space of one or more groups of people from each other on the basis of their group identity. Racial segregation is the separation of people from each other on the basis of race. Racial residential segregation is the separation of people on the basis of race in terms of residence, rather than some other form, such as occupational or educational segregation, or the segregation of public accommodations, such as buses, trains, or theaters."

It is residential segregation that is the primary focus of FIRSTHAND: Segregation, in part because where we live has such a profound impact on what happens to us in life, but also because residential segregation feeds into other kinds of segregation, such as school and church segregation.

But as the Othering and Belonging Institute further elaborates, these dictionary-like definitions mask its everyday uses and connotations, which often overlook important nuance. For example, despite what many people think, “segregated” neighborhoods are not just those that are predominantly non-White; for there to be segregated Black neighborhoods, there must also be segregated White neighborhoods, even if we seldom refer to them in this way. As we think about the firsthand experience of segregation, it’s important to understand that this means understanding what segregated minority neighborhoods are like, as well as what segregated White neighborhoods are like.

Another important distinction relates to the value judgment attached to segregation – namely, that segregation is bad. And here the Othering and Belonging Institute’s discussion is again informative: “None of the foregoing is intended to suggest that all forms of racial separation are harmful. Certain forms of racial solidarity and community, such as an Irish festival or an Italian-American pride parade, religious services, holiday celebrations, or social gatherings are either innocuous or beneficial. But when segregation leads to the inequitable distribution of resources or access to life-enhancing goods or networks, then it is a source of great harm.”

In Chicago – and many cities throughout the country – residential segregation was set up and continues to do just that. It is this form of segregation – the one connected to the distribution of resources and public goods – that is deeply harmful and generates deep inequities in a city. The stories in this series reveal segregation's many inequities and harms while also pointing to forms that are helpful.

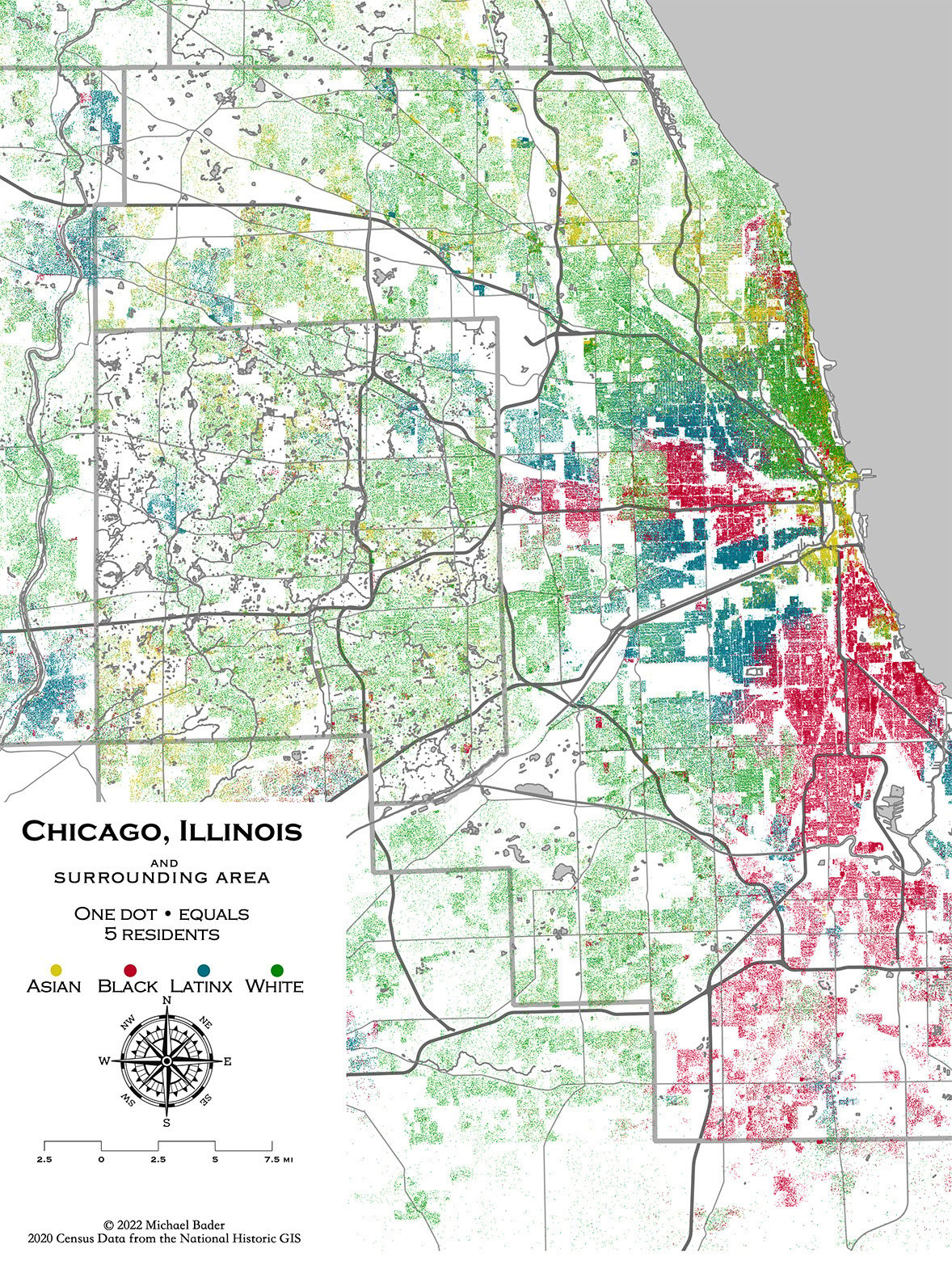

What Does Chicago’s Segregation Look Like?

Demographers have developed many ways to measure and describe Chicago’s residential segregation, but no matter which tool is used, there is no denying that Chicago’s segregation is deep, persistent, and among the highest in the nation. For a detailed analysis of Chicago’s history of segregation, check out the Chicago Urban League’s 2016 report.

One commonly used metric, the index of dissimilarity, shows the extent to which groups are evenly distributed in a city, given its overall population distribution. It ranges from 0 (even distribution) to 100 (complete segregation) and can be interpreted as the percentage of people who would have to move from one neighborhood to another to get an even distribution in each neighborhood. Researchers suggest that places with scores greater than 60 have high segregation. Although Chicago’s segregation has declined from 1980 to 2020, Black-White (81) and Black-Latinx (76) segregation remains extreme, and White-Latinx segregation (61) continues to hover at the high level as well.

As a picture is often worth a thousand words – or in this case, a thousand numbers – here’s a map showing what segregation looked like in 2020 in the Chicago metropolitan region overall.

Image: © 2022 Michael Bader; 2020 Census Data from the National Historic GIS

For an even deeper dive, check out WTTW's interactive map showing a view of the fluctuating – and segregated – demographic makeup of Chicago since the early 20th century.

What Are the Consequences of Segregation?

So much of what happens to a person in their life depends on where they live. In the United States, a person’s racial background has played an important role in determining where they live, due to policies and practices by individuals, industries, and the local, state, and federal government. In fact, residential segregation has been referred to as the “structural linchpin” of all kinds of racial inequality (in wealth, income, health, etc.) in America today.

Thousands of research studies examine the ways segregation harms racial and ethnic minority communities in terms of educational, health, and employment outcomes; exposure to poverty, crime, and environmental pollutants; and the amount of wealth accumulation, social capital, stable local institutions, collective efficacy, and healthy food choices.

In short, racial residential segregation matters because it has been a tool for allocating resources in a way that systematically advantages some while disadvantaging others. In Chicago, the division has resulted in communities of color bearing the brunt of the disadvantages.

What Causes Segregation?

Residential segregation’s causes are multi-faceted and far more complex than can be covered in this brief introduction; interested readers can consult the book, Cycle of Segregation, upon which much of the following discussion is based for details of the argument and references to the research findings. But here are some highlights.

Segregation Was Not an Accident

Segregation did not arise out of pre-existing and neutral preferences for people to want to live with people who looked like them. There were myriad local, state, and federal policies that cemented segregation in our city – things such as redlining, racial covenants, land sale contracts, public housing siting and policies, highway construction, and many more.

The Big Three

Against this backdrop of policies that created the system of segregation, there are three explanations for segregation that scholars have studied and tracked for decades, sometimes called “The Big Three”: economics, discrimination, and preferences.

- Economics, the first of “The Big Three,” reflects what people often think is a cause of segregation: we have racial residential segregation because there are racial/ethnic differences in how much money people can afford to pay for housing. Studies show, for example, that higher-income Black and Latinx people tend to be less segregated from White people than lower-income Black and Latinx people. But other research shows that racial differences in things such as income, education, and wealth can only explain a tiny percentage of the racial differences in where people end up living.

- Discrimination, the second of “The Big Three,” draws attention to the fact that, despite being illegal since the passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act, housing discrimination in the United States persists. Housing discrimination perpetuates segregation because it denies people the opportunity to live in certain neighborhoods based on their racial/ethnic background. And it can take many forms. It can be the landlord who doesn’t return the phone call or email from someone they think is Black or Latinx. It can be the homeowner who tells their agent to avoid showing their home to people of a particular racial/ethnic background. Or the real estate agent who suggests clients might like to look in a different neighborhood, also called “steering.” Or the mortgage broker who targets home buyers in certain neighborhoods with predatory loan products. There are exclusionary acts such as these that keep people out of neighborhoods and homeownership. But there are also acts of non-exclusionary discrimination that happen after someone has moved into such a neigh- borhood. These are behaviors by people in the neighborhood (other residents, police, landlords, etc.), that make life unpleasant or dangerous for people of color through harassment, ignoring requests for repairs, or other acts. Although some forms of housing discrimination, particularly explicit kinds, have declined since becoming illegal, numerous studies show that it persists, even in the online world, and its often more subtle form can make it more diffi- cult to detect.

- Preferences, the third of “The Big Three,” says that segregation happens because we want it that way. The aphorism “Birds of a feather flock together” is often offered as justification for residential segregation. But underneath the surface are layers of complexity, such as whose preferences matter? What is driving those preferences? Research shows that Black and Latinx racial residential preferences are, on average, for racially mixed communities. And there is little support for the idea that Black and Latinx preferences are driven by a strong in-group attraction; rather, a desire to avoid living in predominately White neighborhoods is driven by concerns about the discrimination they might experience in such places. White people express some desire for racial diversity in their neighborhoods, but not as much as people of color. And White preferences are often driven by racial stereotypes and perceptions about racial/ethnic minorities and neighborhoods with racial/ethnic minorities living in them.

Three More Causes of Segregation

In addition to racial differences in economics, preferences, and experiences of discrimination, there are three other, more subtle social processes that shape the information and perceptions we have about our housing options that, in turn, impact where we end up living. For example, our social networks (friends, family, co-workers, neighbors, etc.) expose us to and give us impressions about neighborhoods and communities – even if we’re not looking for a place to live. They tell us where the “good” and “bad” places are to live. And our lived experiences also expose us to places – sometimes brief encounters and other times regular occurrences – and thus shape what we think of a place as a potential neighborhood in which to live. In addition, we learn a lot about communities and neighborhoods through media – social media, traditional media, print, TV, and so on. The reason these factors shape segregation is that in a segregated city, our social networks, lived experiences, and the media are themselves racially segregated or racialized. Therefore, the information about possible places to live that comes from these segregated networks, media, and experiences likely influences us to make moves that perpetuate segregation. Hence, segregation begets segregation.

How Do We Make Segregation Personal?

The background information reviewed above summarizes what researchers and academic studies tell us about the existence, causes, and consequences of segregation. It is based on studies that draw attention to the stark reality of segregation in Chicago through data, numbers, and abstract theories.

But FIRSTHAND: Segregation tells the story of Chicago’s segregation through personal accounts. The stories bring to life the research reports and studies and reveal how the systems, structures, finances, and politics of segregation play themselves out in the lives of everyday Chicagoans. They show how segregation shapes our interactions with each other; how community and meaning are created in our city and how they are shaped by segregation; and how race is constructed and reconstructed everyday through our lived experiences in this segregated city.

FIRSTHAND: Segregation also shines a light on the hope and empowerment of those fighting the system to break down segregation’s inequities. The sometimes-painful stories of the multiple facets of segregation’s inequities are revealed alongside the power within communities to take steps to create a more equitable city for all.

The FIRSTHAND: Segregation series mirrors another compelling, non-academic examination of segregation: The Folded MapTM Project. Creator Tonika Lewis Johnson (who has also contributed an expert talk in this series, see p. 26) uses photography and other multi-media to help us see the stark reality of Chicago’s segregation and its impact on Chicago residents by visually connecting residents who live at corresponding addresses on the North and South Sides of Chicago. The goal of Folded MapTM is to get people talking about segregation. Talking about the personal aspects of it. Talking about the uncomfortable truths. About the dilemmas and impossible choices created by segregation. And about how change is possible and how residents can be part of that change. Because, as Tonika Lewis Johnson says, only by making segregation personal can we end segregation and the inequities that flow from it.

Through FIRSTHAND: Segregation, we see people whose lives embody the personal tolls segregation takes on us individually as human beings and collectively as communities. Like Folded Map™, FIRSTHAND: Segregation offers inspiration to act. To educate ourselves about what is, so that we can imagine what might be possible. To recognize the perils of integration – in the form of racial hostility and displacement – alongside its promises. To acknowledge the costs of segregation – for all of us – and find pathways forward.

You are invited to watch these stories, connect to the people who look like you and who don’t look like you, and see the actions they are taking to question and push back against the inequities of segregation and the costs to our city that flow from its continuation.

Theme One: Segregation’s Costs

The five stories in this theme highlight the varied ways that segregation costs the people and region of Chicago. We see in these stories what everyday life is like when segregation is used to allocate resources and disinvest in segregated Black communities (Ari and Ted Richards and Tia Brown). We see how experiences of discrimination impact how we live, where we live, and our ability to achieve the American Dream of homeownership (Ari and Ted Richards, Tia Brown, Sharon Norwood). And we get a glimpse into the real estate industry itself and efforts to push back against the discriminatory system that has operated to create segregation and disinvestment (Courtney Jones). Finally, we see the cost of segregation through the eyes of residents of a segregated White community and one group’s efforts to address it through increasing affordable housing in their town (Nan Parson).

Quick Facts

- A 2017 Metropolitan Planning Council report concluded that “segregation costs the Chicago region billions in lost income, lost lives and lost potential each year.”

- A joint WBEZ and City Bureau analysis found that between 2012 to 2018, “for every $1 banks loaned in Chicago’s White neighborhoods, they invested just 12 cents in the city’s [B]lack neighborhoods and 13 cents in Latino areas.”

- A joint nationwide study in 2018 by Brookings and Gallup concluded that above and beyond differences in neighborhood features, “across all majority Black neighborhoods, owner-occupied homes are undervalued by $48,000 per home on average, amounting to $156 billion in cumulative losses.”

- A WBEZ report showed that the gap in home values in Black/Latinx neighborhoods versus White neighborhoods grew from a difference of $50,000 more in White neighborhoods in 1980 to more than $324,000 in 2015.

- A Metropolitan Planning Council study found that “in Chicago’s whitest and wealthiest wards there is less than 2.5% affordable rental housing.”

- Despite being illegal, housing discrimination persists. This Vox report summarized a recent study showing that an online inquiry for an apartment from someone with a Black-sounding name was 36% less likely to get a response than an equivalent inquiry from someone with a White-sounding name.

PHOTO: Davon Clark

Ari and Ted Richards

Key Themes: Neighborhood Safety, Disinvestment, Development and Displacement, Discrimination

Ari and Ted Richards have decided to sell their house. When they moved to Jackson Park Highlands it seemed to be a beautiful, tight-knit community. But their concerns about crime and a lack of basic amenities spurred them to search for a new neighborhood. Now finding the right South Side community for their family is proving challenging.

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- What impact do the violence and drug traffic in their neighborhood have on the Richards family and their children? How would you describe the emotions, hopes, and realities of the Richards family in terms of their home and neighborhood?

- As Ari and Ted Richards drive around Bronzeville as part of their search for a new home, what signs of investment and development do they notice? What concerns do they have about it?

2. Connect

- How do Ari and Ted Richards describe their neighborhood versus Hyde Park? How does your neighborhood compare to these neighborhoods? What is it like – or would it be like – to live in a neighborhood without a grocery store?

- The Richardses mention Uber drivers telling them not to go to their own neighborhood and being told by others not to go past 47th Street. Have you ever been told not to go to your own neighborhood? Or other neighborhoods? What did it make you think? What does it/would it feel like to be from a place people are told not to go?

- Ari and Ted Richards are trying to resolve a tension inherent in a city where resources have been allocated differently to White, Black, and Latinx neighborhoods: the need to choose between raising their Black children in the violence of a disinvested neighborhood or subjecting them to the violence of a White neighborhood. How would you resolve that tension? Have you ever had to make a choice like that? How did you decide?

3. Act

- Thinking again about the tension Ari and Ted Richards face in having to choose between accessing resources or having a sense of belonging in the community, what can you or your family or community do to eliminate this tension?

- Ted Richards says, “Police patrols are the only solution to violence that people talk about.” What is the danger of police patrols being the only solution to violence? What other solutions are there?

PHOTO: Davon Clark

Tia Brown

Key Themes: Discrimination, Neighborhood Safety, Disinvestment, Significance of Homeownership

Tia Brown is a proud native of the Austin neighborhood, and she and her husband hoped to return. But the rising cost of housing there put their dream out of reach. After being rejected by a South Side landlord because of their race, the family landed in West Englewood, where their young kids have witnessed violence. Will the family ever find the right home?

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- Tia Brown dreamed of owning her own home. What obstacles did she face? What tradeoffs did she make about where she finally moved?

- We see Tia Brown visiting her childhood home and neighborhood. What did seeing her there and hearing her talk about it reveal about the importance and significance of community to her?

2. Connect

- Tia Brown’s dream neighborhood is one where people know their neighbors, have block parties, and her children can play in the front yard. What are your dreams for your neighborhood? How do they compare to Tia Brown’s? How did you feel hearing her experiences trying to realize this dream?

- Tia Brown talks about being denied a home because she is Black. Has anything like this happened to you? How did you react? If something like this did happen, how would you feel about the neighborhood or the city?

3. Act

- The Fair Housing Act of 1968 made it illegal to discriminate on the basis of race (and other protected classes) in the rental and sale of housing. We know from research that housing discrimination still happens. What is the best way to get rid of it? What can individuals do? What can communities and governments do?

- Tia Brown describes the cycle of good and bad times in her neighborhood – the ebbs and flows of violence. What can be done to ensure that all neighborhoods in Chicago are safe? What can individuals do? Neighborhoods? City officials?

PHOTO: Miguel Zuno, Jr

Sharon Norwood

Key Themes: Discrimination, Significance of Homeownership, Housing Choice Voucher Program, Eviction

Sharon Norwood finds that her government housing voucher comes with strings attached. As a caretaker for an elderly mother and a special-needs child, stable housing is critical, but after being evicted, Sharon feels like she's been discriminated against for her voucher. Not wanting others to go through the same ordeal, she turns to activism.

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- How has the Housing Choice Voucher Program, DCFS, and Eviction Court shaped Sharon Norwood’s ability to raise her family and live her life?

- Why did Sharon Norwood’s grandmother say it was so important to own your own home? What experiences has Sharon Norwood had in her adult life that make her say she was living what her grandmother talked about?

- Sharon Norwood purchased a home in Evergreen Park, which is 74% White. What were her reasons for choosing this neighborhood, and what do those reasons reveal about segregation in Chicago?

2. Connect

- After 11 years of paying her rent on time and using $15,000 of her money to make repairs to her rental home, Sharon Norwood was evicted. How did hearing this story make you feel? Why?

- How important is it to you to own your own home? What obstacles or advantages have you experienced (or do you think you would experience) in becoming a homeowner? How are they the same as or different from Sharon Norwood’s?

- Sharon Norwood decided to move to Evergreen Park, where it was “a hard place to live” because people didn’t want her to live there. Have you ever experienced going somewhere where people didn’t want you? Why did you do it anyway? What were the pros and cons?

3. Act

- What is Sharon Norwood doing to push back against the inequities and experiences she has faced trying to find a home for herself and her family? What strategies is she using?

- We learn in this story that Sharon Norwood faced many barriers and injustices related to housing. From your perspective, what is the biggest barrier she faced? What changes can be made to eliminate that barrier? What, if anything, does that barrier have to do with segregation?

PHOTO: Davon Clark

Courtney Jones

Key Themes: Significance of Homeownership, Real Estate Industry, Disinvestment, Discrimination

Courtney Jones is a Black real estate broker, who knows that the tools of his trade have been used historically not only to segregate people, but to concentrate wealth. After moving from New York to Chicago, he begins to help Black Chicagoans reap the rewards of the city’s real estate growth. In the meantime, Courtney lands a major downtown deal.

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- Suits to Sneakers is a platform that, among other things, elevates the topic of Black homeownership. Why does Courtney Jones say that Black homeownership is so important to addressing racial inequality? Why does he also say it’s important to have Black real estate professionals and Black receivers?

- Courtney and Sanina Jones plan to give their children a piece of property for their college graduation gift. What motivates them to do this?

- During the Receivership Training Program, one of the speakers said, “There’s 80 homes just in the South Shore area that have been purchased by one investor who does not live in the neighborhood and doesn’t care about the neighbor- hood.” What does this statement reveal about real estate and capital in Black neighborhoods? What is the significance of this for the neighborhood itself? For Black homeowners?

2. Connect

- What does homeownership mean to you and your family, personally, socially, and financially? What impact does being a homeowner have on your relationship to your community?

- When you heard that Courtney Jones was the first Black receiver of a high-rise building in downtown Chicago, what did it make you think? How did it make you feel? Why?

3. Act

- Courtney Jones calls himself a Black real estate activist. What are the different ways he and his wife have worked to make a difference in Black homeownership and Black wealth? Which barriers is he trying to address? How can you bring that spirit of activism to the work you do?

- Black homeownership and Black wealth are intertwined. Thinking about the different ways that policies and practices have created inequities for Black families, what are possible solutions to these inequalities? What are the barriers to wealth accumulation and homeownership that individuals or institutions can change? How can these changes be made?

PHOTO: Miguel Zuno, Jr

Nan Parson

Key Themes: Community and Belonging, Integration’s Promises and Perils, Segregation’s Costs, Affordable Housing

Nan Parson has always loved the small-town feel of her suburb, where she has lived for 50 years. But after adopting a biracial son, she realizes that the reason she feels so comfortable in Park Ridge is that most everyone around her is White. As Nan sets out to integrate Park Ridge, it proves to be more challenging than she thought.

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- What are the factors – both today and in the past – that created a segregated Park Ridge?

- “The things attractive to me about Park Ridge are also the things that are difficult about it.” What does Nan Parson mean by this statement, and how does it relate to segregation?

- Nan Parson mentions a few times that integration is healthier and that segregation creates weakness. In what ways does she see integration as healthier and segregation as a weakness?

2. Connect

- Nan Parson remembers thinking the first time she drove around Park Ridge, “This is a place where I could feel comfortable. And now I realized as I look back on that, one reason I felt that way was because everyone I saw was White. And that is what I was used to. We chose Park Ridge because we felt we would fit in.” Have you ever felt this way, whether it’s about where to live or about other settings such as schools, jobs, churches?

- How did you feel hearing Nan Parson and her husband talk about their conflicted feelings toward their segregated community? How are their experiences and feelings the same as the ones you have toward your own community? How are they different?

3. Act

- Nan Parson’s husband comments that he “still struggles with concrete actions that I can take,” to which Nan Parson adds, “We can effect change here. Maybe. A little bit.” What concrete actions have they taken in their lives and in their community? What do you think of their efforts? What challenges have they faced?

- Nan Parson reflects that “the reason we don’t get along is because we don’t know each other.” What can you do as an individual, family, or community to get to know people from other racial/ethnic groups?

Segregation’s Costs

Expert Talk 1

Aaron Allen, Freelance Journalist with stories for City Bureau, Chicago Reader, WBEZ, Austin Weekly News

“Seeing the City with New Eyes”

Photo: Ken Carl

As a kid growing up in Galewood, Aaron Allen wondered why his neighborhood looked so much different than the rest of the West Side. His search for answers pointed him to an unexpected issue – bank lending. He describes the journey that led him through data charts, down memory lane, and into a legendary pink house that made him see the city with new eyes.

Discussion Questions

- What window into the lived experience of segregation does Aaron Allen’s talk reveal?

- What costs of segregation does Aaron Allen’s talk highlight?

- What does Aaron Allen say needs to be done to create a better Chicago?

Expert Talk 2

Monica Peek, MD, MPH, Professor for Health Justice, Professor of Medicine, and Associate Director of the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translational Research at The University of Chicago

“Segregation Is Bad for Your Health”

Photo: Ken Carl

Dr. Monica Peek explains how residential segregation leads to worse health outcomes for Black Americans. In her talk, she navigates our segregated, under-resourced and understaffed health care systems, and chronic disinvestment in commu- nities that have fewer health-promoting resources and attributes.

Discussion Questions

- What window into the lived experience of segregation does Dr. Monica Peek’s talk reveal?

- What costs of segregation does Dr. Monica Peek’s talk highlight?

- What does Dr. Monica Peek say needs to be done to create a better Chicago?

Theme Two: Community, Belonging, and Displacement

These three stories share the themes of the significance of community and belonging, and the pain of displacement or threatened displacement that comes from either specific public policies (Lolly SoulLove, John Nance) and/or gentrification (Karen and Enrique León). The stories highlight the power of community and a sense of belonging that come from sharing residential space with people from the same background. But each story also points to the precarity of those segregated spaces when they are accompanied by an unequal distribution of resources.

Quick Facts

- According to a 2016 study by the Metropolitan Planning Council, Pilsen and Logan Square were Chicago’s most gentrifying neighborhoods. From 2000 to 2016, Pilsen lost 26% of its Latinx population, and its White population grew by 22%. In Logan Square, the percentages were 35% and 44%, respectively.

- Chicago’s Plan for Transformation began in 2000 by then-Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley. A 2017 joint study by WBEZ and Northwestern University’s Medill Social Justice News Nexus summarized the plan’s goal: “To demolish and replace 18,000 ‘obsolete’ public housing units and create ‘mixedincome communities’...[that would serve to] ‘reintegrate low-income families and housing into the larger physical, social and economic fabric of the city.”

- This same WBEZ study found that after 17 years and $3 billion dollars, just under 8% of the 16,846 displaced households were living in the Plan for Transformation’s envisioned mixed-income housing.

PHOTO: Miguel Zuno, Jr

John Nance

Key Themes: Community and Belonging, Significance of Homeownership, Reparations, Economic Development

John Nance’s suburb made national news in 2019 when it established America’s first reparations program for Black residents. As a Black Evanston homeowner, Nance would seem to be well-positioned to benefit from the program. But instead, he says “No, thank you,” and packs up for another suburb.

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- “We had our whole life in West Evanston. We didn’t care about other areas of Evanston.” What childhood memories does John Nance have of West Evanston? What was it like to grow up in this segregated Black community? Is this a case of “good” segregation? Why or why not?

- “The problem is not integration. The problem is economic development.” What does John Nance mean by this? What impact did the disinvestment in the Black community in Evanston have on the community in general and on individual families?

- What did John Nance’s stories about his childhood in West Evanston reveal to you about the meaning of community and belonging? What parts of the story stood out to you?

2. Connect

- When you heard John Nance’s story about losing his childhood home because he had to take care of his sick mother and couldn’t take care of the home and the mounting medical bills, what did you think and feel?

- John Nance pointed out that people living in East Evanston could always buy in West Evanston, but not vice versa. And more recently, he could get a lot more house and property for his money in Country Club Hills (87% Black) than in Evanston (18% Black). How did you feel hearing about these stark differences? Did his story make you feel differently about these economic differences? If yes, in what way?

- John Nance says that they “gutted the soul of the community” and “ran people out of town.” What does our society lose when communities and people are displaced? What impact did it have on you when he described the loss of his community this way? What would it feel like to lose your community?

3. Act

- John Nance is not a fan of the reparations program in Evanston. Why not? What would he like to see instead? What do you think of his ideas?

- The story talks about the barbershop as the hub of Black history in Evanston. What can be done to preserve this history? Why would it be important to do so?

PHOTO: Miguel Zuno, Jr

Lolly SoulLove

Key Themes: Displacement, Public Housing, Community and Belonging

Lolly SoulLove returns to the site of the public housing project she once called home for the first time since it was destroyed during the Chicago Housing Authority’s Plan For Transformation. It stirs up a wave of emotions: While outsiders often saw public housing as an ugly manifestation of segregation, Lolly recalls a strong sense of community.

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- What does community mean to Lolly SoulLove? What are the important elements of community? What are her memories of her community and what impact did housing policy have on those memories?

- In addition to destroying their homes when the Robert Taylor Homes were demolished, what else does Lolly SoulLove feel the city was doing to continue to destroy their community?

- Much of this story is about how other people view communities and especially how people such as cab drivers, politicians, and bureaucrats who run housing programs devalue Black communities. How did these perceptions impact the residents of the Robert Taylor Homes? How did they affect their lives, psychologically, socially, and materially?

2. Connect

- “Let residents be in control.” In what ways did this happen or not happen when the Robert Taylor Homes were demolished? What was the “pink slip”? What would it feel like to be given a pink slip and have little control over where you moved next?

- What is the “sadness that stems from segregation”? How is it the same as or different than you expected?

- What surprised you the most about this story?

3. Act

- “They destroyed the Robert Taylor Homes, but they did not destroy the love.” In what ways do the former residents make sure the love survives?

- “Don’t be embarrassed about where you came from.” What does it mean to be from a place that other people think is bad? What is Lolly SoulLove’s response to that?

PHOTO: Davon Clark

Karen and Enrique León

Key Themes: Displacement, Gentrification, Community and Belonging, Significance of Homeownership

Karen and Enrique León struggled to stay in their rapidly gentrifying neighborhood on musicians’ salaries. The longtime Pilsen residents are mariachis, and the money they make from live performances has dipped with the closure of neighborhood clubs. Now an experiment in cooperative housing is giving them hope.

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- How did Karen and Enrique León feel about their home in Pilsen and the Pilsen neighborhood? What did they love and value most?

- Enrique León is a mariachi musician. What is the cultural and economic significance of him being a musician? How did his profession impact the family and the neighborhood?

- The story focuses on the value of living in a Latinx community for Karen and Enrique León. What are the benefits? Are there any costs to their family?

2. Connect

- How did Karen and Enrique León feel that the developments that impacted housing and businesses threatened their way of life economically, socially, and emotionally? Have you experienced something like this? If so, how did you feel; if not, how do you think you would feel? What would matter the most to you?

- What does this story reveal about what it means to be raised in a community where you belong? Were you raised in such a community? If so, what features of the community made you feel that you belonged? If not, what made you feel you did not belong?

- What did you learn from this story about the significance of homeownership to Karen and Enrique León and other families in Pilsen? How is their perspective the same as or different from your own? Is there a special significance for im- migrant communities?

3. Act

- Members of the community created a way to protect residents in the face of the development in Pilsen and to stave off displacement. What did they do? How did they protect and support themselves?

- Two important themes of this story are displacement and gentrification. What, if anything, should city leaders do about this? How can collective ownership and other alternative pathways to homeownership be supported?

Community, Belonging, and Displacement

Expert Talk 1

Lisa Yun Lee, Executive Director, National Public Housing Museum and Associate Professor Public Culture and Museum Studies, University of Illinois Chicago

"Have your Mooncake, and Eat It, Too"

Photo: Ken Carl

Lisa Yun Lee describes how a question from a shopkeeper in Chinatown led to her awareness of the differences between imposed segregation and self-segregation as an act of resistance and survival. In her talk, she discusses the balance of preserving cultural diversity across Chicago’s neighborhoods while challenging inequity.

Discussion Questions

- What window into the lived experience of segregation does Lisa Yun Lee’s talk reveal?

- What lessons of community and belonging does Lisa Yun Lee’s talk highlight?

- What does Lisa Yun Lee say needs to be done to create a better Chicago?

Expert Talk 2

Soren Spicknall, Data Engineer, The Movement Cooperative

”Unlearning the Bad Advice That Segregates Chicago”

Photo: Ken Carl

When you move to a new neighborhood, it’s often the first things you hear from residents that have the biggest impact on how you view your surroundings. Soren Spicknall discusses how his initial perception of Chicago was shaped by estab- lished stereotypes and boundaries, how he came to realize that these boundaries were often rooted in racism, and how he learned to navigate this city with clearer eyes.

Discussion Questions

- What window into the lived experience of segregation does Soren Spicknall’s talk reveal?

- What lessons of community and belonging does Soren Spicknall’s talk highlight?

- What does Soren Spicknall say needs to be done to create a better Chicago?

Theme Three: Integration’s Promises and Perils

The three stories in this theme explore the promises of integration while also drawing attention to its perils. We see that simply creating diverse spaces does not translate into achieving integration or advancing equity. Segregation as a tool of oppression can find little to redeem itself – except, of course, for the dominant group. But integration without an understanding of decades of oppression, racial tensions, and discrimination does not advance equity. Integration efforts must be intentional to ensure that people are not displaced and that individuals are not simply trading one form of violence for another. This series of stories uncovers the complexity and hope of integration in Pastor Ricky Brown. In the case of Rashad Bailey, we see the heartbreaking perils of integration. And in Rachael Toft’s story, we learn about the unusual merger that sought to create an integrated school in a segregated city.

Quick Facts

- According to a Duke University report, “83% of American congregations remain overwhelmingly White or Black or Latinx or Asian.” At the same time, the percentage of people in congregations where no single ethnic group makes up 80% or more of the participants has grown from 14% in 1998 to 25% in 2018-2019.

- A Pew Research Center survey found in 2020 that 77% of U.S. Blacks said that predominantly Black churches have done “some” or “a great deal” to help Black people move toward equality in the U.S. This compares to 89% who said civil rights organizations and 54% who said the federal government had done “some” or “a great deal.”

- The Woodstock Institute found that in Chicago, "businesses in predominantly minority census tracts constituted an average of 15.1% of businesses, but they received only 8.2% of the number of CRAreported loans under $100,000 and only 6.7% of the total amount of those loans. If those businesses had received the loans in proportion to their share of businesses overall, they would have received more than 23,000 additional loans totaling over $335 million between 2012 and 2014.”

- UIC’s Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy (IRRPP) report used a common indicator of segregation, the index of dissimilarity, which measures the extent to which the racial composition of schools mirrors that of the racial/ethnic mix of the overall district school population. They found that CPS’s school segregation is very high (above 60 is considered high). In 2010, the scores were BlackWhite (87.4), Black-Latinx (85.0), and Latinx-White (68.7).

- The IRRPP report also found that in 2014, “91.1% of Black students and 88.7% of Latinx students attended CPS schools where more than 75% of the student population were eligible for free or reduced price lunch (an indicator of low income).”

PHOTO: Miguel Zuno, Jr.

Pastor Ricky Brown

Key Themes: Integration’s Promises and Perils, Religion and Spirituality, Disinvestment, Segregation’s Costs

Ricky Brown is an airplane pilot and a pastor, who is determined to establish a multiethnic church on the South Side. As a Black man who grew up in Mississippi he is no stranger to segregation. But he wonders how Chicago's segregation might stand in the way of his dreams for a truly integrated faith community.

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- Pastor Ricky Brown says, “We cannot heal and move forward without acknowledging the pain of the past.” What are the pains of segregation that the story refers to? What are other pains of segregation?

- Pastor Ricky Brown points out that an integrated church is not just “getting people with different skin tones together in the same room.” What else is it?

- Pastor Ricky Brown says that creating an integrated church was a risky thing to do. What makes it risky? Is integration always risky? And risky for whom?

2. Connect

- Pastor Ricky Brown talks about taking the Red Line ‘L’ train and witnessing segregation as he moved from the North Side to the South Side of Chicago. Have you ever had this experience? If so, what did you notice about what you saw and how you felt?

- What most interested you about the story of the partnership between the two churches? Did anything surprise you or inspire you? If so, what?

3. Act

- The churches created a partnership to go from “presence to prosperity to action” using what they call justice deposits. What are justice deposits, and what do they hope to accomplish with them? What else can churches do?

- Pastor Ricky Brown notes that we can’t “clear up a 400-year head start” in our lifetimes. But what can we do in our lifetimes? What other institutions besides churches can take action? And what action?

PHOTO: Miguel Zuno, Jr.

Rashad Bailey

Key Themes: Black Business Owners, Integration’s Promises and Perils, Discrimination

Rashad Bailey says his restaurant is a reflection of his personality: young, hip, and “all about taste.” And like Rashad, most of his clientele are Black in a North Side neighborhood that is overwhelmingly White. The restaurant begins to meet resistance from its neighbors – some of it subtle, and some of it overtly racist.

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- What did Rashad Bailey’s story reveal to you about the perils of integration for Black people in general and Black business owners in particular?

- When Rashad Bailey is told “go back where you came from,” what does it does it reveal to you about segregation? What does it reveal about privilege?

- What expenses – emotional and financial – does Rashad Bailey have because he’s a Black business owner with Black customers in a White segregated neighborhood? How does being in a White segregated neighborhood impact his customers?

2. Connect

- In the story, we see that the police are around when Rashad Bailey doesn’t need them and not there when he does. How did you feel when you saw this play out? Are there ways in which segregation creates this dynamic? Or does this dynamic contribute to segregation?

- With whom did you most identify? From whom did you learn the most? Whom would you most like to ask a question, and what is that question?

3. Act

- Rashad Bailey feels like he’s “at war.” What does that mean? And what has he done to respond to this treatment? What other responses might there be?

- How have the stereotypes that people have about Black people impacted Rashad Bailey’s experiences and the experiences of his customers? How does segregation play a role in creating these stereotypes, and how might they be broken down?

PHOTO: Miguel Zuno, Jr.

Rachael Toft

Key Themes: Community and Belonging, Integration’s Promises and Perils, Segregation’s Costs, School Segregation

Rachael Toft was committed to sending her kids to Ogden, their neighborhood public school. It served relatively affluent families like hers in Streeterville and the Gold Coast that is, until Ogden undertook a merger with Jenner, a school on the site of the former CabriniGreen Homes. Rachael reflects on the challenges of this experiment.

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- What does Rachael Toft mention when describing what she likes about her neighborhood? Why was she committed to sending her children to a public school?

- Chicago Public Schools merged the Ogden and Jenner schools to create one school with two campuses. What were the reasons for the merger, and what concerns did people have about making this merger?

2. Connect

- Rachael Toft believes that “my kids aren’t in school only to learn math and a skill, but how to work with their peers and how the world actually is.” Thinking about your own education, what did/have you learned the most other than academics? Is/was your school racially, economically, or culturally diverse? How did that impact what you learned?

- When you heard Rachael Toft’s description of the public forums, what was your reaction to the concerns the parents expressed?

- This story is told from the perspective of a White parent at Ogden; how do you think the students and parents from the Jenner school felt about the merger? What do you think the experiences of Black families and

3. Act

- Rachael Toft decided to send her children to the merged Jenner/Ogden school even though many of her friends decided to leave. Why did she stay and what does she see as the benefits of this decision?

- In a segregated city, schools are often also segregated. As Rachael Toft points out, segregation often means that resources are segregated and unequal. What can cities do to address these inequalities in a way that benefits all students?

Integration’s Promises and Perils

Expert Talk

José Rico, Executive Director of Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation Chicago

“Truth Telling About Violence and Healing”

Photo: Ken Carl

Chicago is a city of ZIP codes that mark cultural and racial differences and inequities. José Rico describes how understanding violence in a city known for its segregated neighborhoods is necessary for true healing and systemic transformation.

Discussion Questions

- What window into the lived experience of segregation does José Rico’s talk reveal?

- What lessons of integration and segregation does José Rico’s talk highlight?

- What does José Rico say needs to be done to create a better Chicago?

Theme Four: Building Bridges Across Communities

Segregation is by definition about separation. Separating people from people; communities from communities. In Chicago, segregation has left us with White, Black, Latinx, and Asian communities living separate realities. In this section, we hear four stories about people working to build bridges from one community to the other (Chris Javier). Of efforts to find shared humanity (Pilar Audain Reed and Susana Banuelos). To find – and come together – to overcome shared challenges (Father Larry Dowling). And to use music to understand and bridge our segregated city (Jason Ivy). Through this group of stories, we see ways to use what we have in common to heal wounds, build power, and uplift communities. In short, to create bridges throughout a segregated Chicago.

Quick Facts

- Between 1980-2020, Chicago’s Asian and Latinx populations grew from 2% to 7% (Asians) and from 14% to 30% (Latinx). At the same time, the percentage of the population who are Black and White declined: 39% to 29% (Black) and 43% to 31% (White).

- According to a UIC Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy (IRRPP) report, Asian Americans are the smallest but fastest growing of Chicago’s major racial/ethnic groups. The largest Asian ethnic groups are Chinese (31.1%), Indian (21.1%), and Filipino (19.1%), and 69% of Asians are immigrants compared to 39% of Latinx, 14% of White, and 3% of Black Chicagoans.

- In Chicago, Black-White and Black-Latinx segregation levels are especially high. Asian-White segregation is comparatively low (but see next fact below), and Latinx-White segregation falls in the middle.

- IRRPP’s report explains that traditional indexes of segregation are unreliable for numerically small groups such as Asians in Chicago, but they show that Asian Americans are concentrated in Chinatown (where there are few Blacks, Latinxs, and Whites). In other Chicago neighborhoods, Black-Asian segregation is particularly stark.

- In 2018, the Collaborative for Community Wellness examined the availability of private practice, licensed mental health clinicians in Chicago and found that zip codes in the city center had more than 324 licensed clinicians per 1,000 individuals compared to most zip codes in the West, Southwest, and South Sides of Chicago where there was fewer than 1 licensed clinician per 1,000 residents.

PHOTO: Davon Clark

Chris Javier

Key Themes: Immigration, Building Bridges, Neighborhood Safety, Religion and Spirituality

Chris Javier leads an effort to address anti-Asian hate in the wake of a wave of hate crimes in Chinatown. It spurs Chris to start thinking about the nature of segregation: while the city’s divisions are clearly taking a toll on his community, he also sees how enclaves like Chinatown offer a safe space for culture to thrive.

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- Chris Javier shares that there are both upsides and downsides to Chinatown; what does he mean that there needs to be a “nuanced look” at it? What are the benefits of segregation for people living in Chinatown? What are the costs of segregation for people living in Chinatown?

- “There’s so much pain that goes unaddressed.” What pain is Chris Javier referring to? What causes it and what can be done to alleviate it?

- What are the unique experiences of Asians in Chicago? How are Asian experiences different from and the same as other racial/ethnic groups?

- Some would call Chinatown a self-segregated neighborhood. How is it the same as or different from Black segregated neighborhoods? White segregated neighborhoods? Latinx segregated neighborhoods?

2. Connect

- What does it mean to be safe in one’s own neighborhood? Have you felt unsafe in your own neighborhood? What made you feel this way? What could you do about it?

- Chris Javier talks about being able to straddle multiple cultures because he was raised in a White suburb but attended church in Chinatown his whole life. What were the benefits and costs for him personally of these two different experi- ences? Have you had experiences like this? If so, what were they like?

3. Act

- What factors threatened the peace in Chinatown? What actions did Chris Javier’s church take to support community members? What other solutions would help community members feel safe?

- Chris Javier suggests that we need to build bridges between neighborhoods and communities. What ways can individuals and institutions work to create bridges? What benefits are there to creating bridges?

PHOTO: Davon Clark

Father Larry Dowling

Key Themes: Building Bridges, Health Care Inequities/Mental Health, Religion and Spirituality, Disinvestment

Father Larry Dowling is a White priest ministering to a predominantly Black population in North Lawndale, which borders majority-Latinx Little Village. Despite longstanding tensions between the neighboring communities, Father Larry discovers that they have so much more in common. He sets out to build bridges.

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- What does Father Larry Dowling see as the consequence of the separation of Black and Latinx neighborhoods from each other? And from White neighborhoods?

- Father Larry Dowling points out that both North Lawndale and Little Village are experiencing trauma from gun violence, domestic violence, drugs, etc., and this leads to a shared problem around mental health. What similarities and differences do each of these communities have in terms of structural and cultural issues related to addressing mental health problems? What role does segregation play in creating mental health problems?

- Father Larry Dowling describes his observation of how some people approach inter-group relations: “Separate them and then play them off each other.” In what ways are Black and Latinx communities played off each other? What, if any, role does segregation play in creating conflict and tension between Black and Latinx communities?

2. Connect

- Father Larry Dowling moved from a White church to a Black church, and he experienced culture shock. Have you ever been in a situation like this? How did it feel? What did you do? What worked or didn’t work?

- The community created the Love Ride, a bicycle ride of unity through their neighborhoods. What message does the Love Ride send inside and outside the community? How did you feel when you saw the scenes from the Love Ride?

3. Act

- “People want to divide us, but there is greater power in unity and believing that we deserve what other people have.” What is Father Larry Dowling doing to create unity? What challenges does he face? What are the outcomes of doing so?

- What other events or efforts can you as an individual or a resident of a community create or make to build unity across racial groups? How can you help repair the broken bridges and build new ones, such as Father Larry Dowling mentions?

PHOTO: Ajani Akinade

Pilar Audain Reed and Susana Banuelos

Key Themes: Immigration, Racial Healing, Building Bridges, Disinvestment, Religion and Spirituality

Pilar Audain Reed and Susana Banuelos are “racial healing practitioners” – they go to communities that have experienced incidents of violence or racial discord to bring about healing with rituals such as "sage corners." But just as important as these rituals is the example they set through their cross-cultural friendship.

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- Pilar Audain Reed and Susana Banuelos come from immigrant backgrounds. How does this join them together, and how are their experiences different from each other? What have they each learned about race in America? What lessons were in common and what lessons were unique?

- Pilar Audain Reed and Susana Banuelos are joined by a common desire to “do the work to prove that solidarity heals.” In what ways can solidarity heal? What are the wounds that it needs to heal?

- What role do bridges play in breaking down the problem of segregation? In what ways are Pilar Audain Reed and Susana Banuelos acting as bridges, and what do we learn from them?

2. Connect

- How do Pilar Audain Reed and Susana Banuelos' ancestors and cultures shape the work they do toward racial healing? How can cultural similarities and differences be used to either create or break down segregation? How do your ancestors and culture impact your values and beliefs about segregation?

- Pilar Audain Reed and Susana Banuelos talk about the cost of segregation on their personal lives. Are you missing out on anything because of segregation? If so, what?

3. Act

- Pilar Audain Reed and Susana Banuelos intentionally go to places that are disinvested in and to places where one or the other of them will stand out. Why do they do this? What are they hoping to accomplish?

- As illustrated in the story, through such activities with others as sharing a healing circle, prayer, and burning sage, people come to understand each other better. This can be one of the keys to ending segregation, because “people tend to fear what they don’t understand.” What do you think about this statement? Do you find this to be true in your own life? If so, in what areas? How can we overcome the fear of others who are different from us?

- Pilar Audain Reed talks about a time when she had to "get clearance" to visit her best friend who was Latinx and lived in Little Village. What impact does a sense of having to "get clearance" have on our understanding of the city and who belongs where? How do we break those barriers down?

PHOTO: Davon Clark

Jason Ivy

Key Themes: Community and Belonging, Integration’s Promises and Perils, Segregation’s Costs, Building Bridges, Culture and Art

Jason Ivy has the right tools to navigate his segregated city: he is a musician and visual artist, who uses these forms of self-expression to engage in dialogue about the city’s divides. And he speaks several languages, so he can spark conversations with the city’s diverse communities.

Discussion Questions

1. Reflect

- Jason Ivy believes that “the arts industry in Chicago doesn’t thrive like it should.” What does he believe are the reasons it doesn’t thrive?

- How does Jason Ivy think that segregation impacts the city and the artists who work here?

- Jason Ivy says, “You cannot escape segregation in Chicago. You cannot fail to notice it.” What signs of segregation does Jason Ivy point to? What differences does he observe?

- Jason Ivy observes that “every neighborhood has a different feel to it.” In what ways does Jason Ivy think this is good – and in what ways is it bad?

2. Connect

- Jason Ivy experienced many different racial contexts during his school years that impacted how he thinks about race, culture, division, and the city. How do you think your own school experiences shaped your perspective on these issues?

- Jason Ivy’s ideal Chicago is one that would “feel like home all over the city.” What is your ideal Chicago?

3. Act

- In what ways does Jason Ivy connect to people from different backgrounds?

- What can you do to create opportunities to connect through art and culture to other groups or communities in Chicago? What makes it hard to do this? What might the benefits be, both for you personally and for the city?

Building Bridges Across Communities

Expert Talk

Tonika Lewis Johnson, Creator, Folded Map™ Project; Co-founder, Englewood Arts Collective and Resident Association of Greater Englewood

“Segregation Limits Our Relationships”

Photo: Ken Carl

Tonika Lewis Johnson describes how attending a large, multi-racial Chicago public high school in the ’90s taught her empathy, expanded her worldview, and revealed the impacts of segregation...all while giving her lifelong friend- ships she wouldn’t have had otherwise.

Discussion Questions

- What window into the lived experience of segregation does Tonika Lewis Johnson’s talk reveal?

- What lessons about the value of building bridges across communities does Tonika Lewis Johnson’s talk highlight?

- What does Tonika Lewis Johnson say needs to be done to create a better Chicago?

Digging Deeper: Discussing More, Learning More, and Taking Action

Discussing More

Synthesizing the Stories

Reflect on the stories within each theme and consider the following:

- Which person or story stood out the most to you? What made them stand out? Was it because their story surprised you? Inspired you? Challenged you? How or why?

- How do the stories connect to each other and to the core theme of the section you watched?

- What do the stories in this theme tell you about segregation in Chicago that you didn’t know before?

Reflecting on the Overall Series

- At the conclusion of the discussion/event, the leader is encouraged to facilitate an overall discussion about the series (or the set of stories the group watched), focused on action steps. In addition to the specific actions discussed for each story, the leader can pose the following more generic questions (drawn from this source).

- What did you learn from FIRSTHAND: Segregation that you wish everyone knew? What would change if everyone knew it?

- If you could require one person (or one group) to view FIRSTHAND: Segregation, who would it be? What would you hope their main takeaway would be?

- This series is important because ...

- I am inspired by this series (or discussion) to ...

Learning More

Learn More about Theme One: Segregation’s Costs

- For a discussion of the causes and consequences of racial residential segregation and an interactive mapping tool to explore patterns all over the country (including Chicago), check out this Othering and Belonging Institute report.

- To explore the fluctuating – and segregated – demographic makeup of Chicago since the early 20th century, check out WTTW's interactive mapping tool.

- To learn more about why eviction matters and what the patterns and trends are nationwide, go to the Eviction Lab, especially here. To find eviction data specific to Chicago, check out the Lawyers’ Committee for Better Housing data portal and reports.

- For insights about the politics and patterns of affordable housing in Chicago, see this report by the Chicago Area Fair Housing Alliance.

- To learn more about past housing policies that impacted Chicago, check out this interactive mapping tool from Lake Forest College that digs deeper into the practices of redlining, blockbusting, and racially restrictive covenants, and this Duke University report on predatory land sale contracts.

- To learn more about racial/ethnic differences in homeownership, returns to homeownership, and the wealth gap in Chicago’s White, Black, and Latinx communities, see this report and this report from UIC’s Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy.

- To learn more about Source of Income Discrimination (which is based on how a person pays for housing, including those with housing choice vouchers) and where it is and is not legal, go to the Illinois Coalition for Fair Housing.

- If you think you have been the victim of housing discrimination, you can get free information and support at Fair Housing Centers, including the Lawyers’ Committee for Better Housing and IC Law’s Fair Housing Legal Clinic.

Learn More About Theme Two: Community, Belonging, and Displacement

- To learn more about what displacement and gentrification are, see the useful explainers created by the Urban Displacement Project.

- To read more about gentrification in Pilsen specifically, go to this WTTW report.

- To hear more stories from public housing residents and learn more about the history of public housing, check out the National Public Housing Museum in Chicago.

- To see interactive tools showing patterns of displacement and gentrification, check out the Urban Displacement Project’s Map of Chicago’s Gentrification and Displacement and the DePaul University’s Institute for Housing Studies “Mapping Displacement Pressure in Chicago” tool and fact sheets.

- To learn more about reparations, start with Ta’Nehesi Coates’s “The Case for Reparations,” which includes substantial discussion of segregation in Chicago.

- To learn more about Evanston’s history of redlining and to see maps of its segregation, check out this article about an exhibit created by Morris “Dino” Robinson, founder and executive director of the Shorefront Legacy Center.

Learn More About Theme Three: Integration’s Promises and Perils

- See this Vox report and this article by Elijah Anderson on the reception Black people get when they enter “White spaces.”

- For a series of short essays exploring the question of “What we mean by integration,” including a lead essay, “The Problem of Integration” by Northwestern University sociologist Mary Pattillo, check out this NYU Furman Center series.

- To hear stories of Chicago’s Black youth about where they are made to feel they don’t belong, check out Tonika Lewis Johnson’s Belonging: Power, Place, and (Im)Possibilities project.

- To learn more about Black-owned banks, see this WBEZ story about the former CEO of Chicago’s last Black-owned bank, this Investopedia report on Black-owned banks nationwide, and this Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago study on minority-owned banks and whom they serve.

- For a closer look at multiracial congregations, listen to NPR’s story featuring research by sociol- ogist Dr. Korie Edwards.

- For more about the causes of school segregation, check out this Vox “Explainer”.

Learn More About Theme Four: Building Bridges Across Communities

- To learn more about the W. K. Kellogg Foundation’s Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation initiative, check out their website and the Implementation Guidebook.

- To learn more about Chicago’s efforts around racial healing, check out the Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation of Chicago website.

- To learn more about Latinx and Asian communities in Chicago, check out all the State of Racial Justice in Chicago reports from UIC’s Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy.

- To read about an initiative in Chicago to address systemic racism and segregation in the arts and through the arts, see this blog post and short video and check out this organization.

Taking Action

What did you learn about the personal, institutional, and political forces that keep segregation in place? What can you do to help break it down? Or to be a bridge? Here are some places to start.

- Think about your own neighborhood, school, or workplace and how it is impacted by segregation – is your neighborhood, school, or workplace more advantaged or less advantaged because of segregation? How can you act to create more equity? Check out Chicago United For Equity for some resources and tools to get you started.

- Learn more about neighborhoods outside of your own in the city of Chicago and think about how segregation has impacted your twin neighborhood by completing the Folded Map™ Action Kit.

- Support or volunteer with local nonprofit organizations focused on housing and equity. Several are mentioned in the series’ stories and in the Learn More section of the discussion guide, above.

Tips for Planning the Discussion

Laying the Groundwork for Dialogue about Sensitive Topics

FIRSTHAND: Segregation deals with a subject matter – race in America – that can be difficult to talk about. The topic can feel personal, is complex, and requires nuance. The purpose of this guide is to help foster respectful and productive conversations with a goal not to lay blame, but to build understanding. The goal of the conversations is not to debate and win points, but to listen and deepen our thinking and awareness. To create a discussion where everyone learns from other perspectives – those shared through the stories and those of other members of the discussion group.

To this end, facilitators might consider sharing these reminders (excerpted and adapted from PBS’s POV Discussion guide) with their attendees:

“A Note about Facilitation. This series raises issues that may provoke difficult conversations. Some people may deflect their own discomfort with those issues by focusing on the decisions and behaviors of the individuals and institutions featured in the series. To avoid getting bogged down in unproductive personal attacks, you might remind participants that:

- The purpose of this discussion isn’t to approve or disapprove of the actions of the people in the stories, but to learn from their experiences so we can make our own families and communities better.

- Issues that come up for one family or community are not more important than other issues. This event is going to focus on what we can learn about segregation’s impact from all of the experiences shared in these stories.

- Joking can be a fun way to interact with friends, but since we don’t have that relationship with everyone in the room, and since insults, even in jest, can be easily misunderstood, that type of joking is best reserved for other occasions.”

Tips for Watching the Stories and Getting the Conversation Started

- Watching the Stories: Before viewing the stories, suggest to your audience that they pay attention to the details of the story – the relationships, the references that the subjects make, and the environment that they are in. Pay attention to your own responses. Often, our deepest insights can come when we pay attention to our own emotional and visceral reactions. Choose not to turn away, as your own reactions are opportunities that can lead to meaningful discussions. Stay open to your own reactions to the feelings, thoughts, and ideas shared, as they touch your own fears, anxieties, anger, grief, and joy. As much as possible, make notes of your responses as you watch the stories, as they can be meaningful during later discussions.

- Getting the Conversation Started: After viewing the stories, discussion leaders can encourage viewers to spend a bit of quiet time reflecting on what they have seen.

Tips for Setting Up the Discussion

- Consider Timing: The entire series is approximately 211 minutes long. You may prefer to watch portions of the series or to select from the themes (or to select some stories within each theme). You may also want to allow at least an hour after the screening for discussion.

- Follow Up: The series will raise many concerns that will not be resolved after the screening. Find time to follow up with viewers, offering opportunities for resource sharing with others working around these issues. Throughout the guide are links to reports and local and national organizations and resources related to segregation to assist you.

- Consider Your Audience: Although unrated, the series is best viewed by mature audiences and teens. There is little to no visual content that may be considered objectionable; however, the subject matter deals directly with segregation, struggles with neighborhood violence, issues related to poverty, and discussions of faith and religion. Do not hesitate to ask an expert (social worker, mental health worker, community practitioner, scholar, etc.) to help guide your discussion or be present for the screening and discussion.

A Timeline to Prepare

2-4 Weeks Prior

- Develop your invitation list.

For an In-Person Event

- Select a location that allows for good screening and ensure that proper seating and audio-visual equipment will be available and set up.

- Be mindful of any security needs. Many venues require security based on the number of attendees.

- Be sure that your location is accessible to all. Consider the visual, auditory, language, and physical needs of your viewers.

- Design and send an e-mail that describes the name and purpose of the series, the purpose of the discussion, the format of the post-screening discussion (panel discussion, moderated Q & A, small group discussions, open discussion format, peace circles, snacks or dinner, etc.). If you are planning special aspects, make sure to include this information in your invitation, as well.

- If you are in a setting that does not allow for a minimum of two hours to both watch and discuss the series afterward (such as during school hours or at an after-school or outreach program), you may want to show a selection of stories from across the themes or perhaps focus on just one of the themes. Make sure you have allowed enough time for set up, as well.

For a Virtual Event

- Follow the same recommended planning procedure for an in-person event.

- Make sure to create the virtual conference event with the link that can be shared with the invited guests. It is important to check for the maximum capacity allowed on the event before sending out the invitation. If restricted to a certain number of participants, include that information on the invitation.

- Check for videoand audio-sharing settings on the virtual platform so that with the system sound on, your computer can be heard by the invited viewers. Please make sure to turn off all other apps in the background that might make noise, e.g., email alerts, notifications, etc.

2 Weeks Prior

- If having an in-person event, make reservations for any food or beverages you plan to have for the discussion and decide whether you want to offer this before, during, or after watching the series or discussion.

- Prepare an agenda. This can be as formal or informal as you wish; however, you may want to consider who will introduce the series, the start time of the screening and the subsequent start time of the discussion, who will facilitate the discussion, and wrap-up and evaluation procedures. The discussion guide can serve as a tool to provide discussion questions, prompts, and resource sharing related to the series in order to have a robust and meaningful discussion.

1 Week Prior

- Send a reminder e-mail to those who have RSVP’d and those who have not.

- Consider sending RSVP’d guests a link to the series’ website and social media pages to engage them with information about the series and get your guests excited about the event. You may want to consider sending a link to one of the arti- cles listed in the Learn More sections of the guide to prepare them for the screening and discussion.

3 Days Prior

- Reconfirm your location and any food and beverages for an in-person event.

- You may want to send a final e-mail to RSVP’d guests as a reminder and send any links to the late RSVPs.

- Arrive early for set up and check all audio-visual equipment (sound, lighting, etc.).

- If holding an in-person event and your venue is large, be sure to place signs throughout the venue to direct your guests to the screening area.

- Have your agenda on hand.

- Ensure that all participants know their roles and have prepared in advance.

- Welcome everyone and introduce the series!

Day After the Event

- Send a thank-you note to all guests who attended and include any follow-up activities.

- Open up opportunities to stay connected and share ideas for taking future actions after viewing the series.

About the Filmmaker