Architect Scott Merrill | Biography

Biography: Scott Merrill

“I think, about architecture right now, that no matter what types of buildings you’re interested in, there’s renewed interest in regionalism,” said Architect Scott Merrill. “What’s nice about architecture is you can understand it intellectually, you can understand it in terms of engineering, you can understand it instinctually, and you want most people to be able to respond to it instinctually.”

Merrill as a student in 1st grade

Born in Oxford, Ohio, Scott Merrill didn’t necessarily plan on becoming an architect while growing up in the suburbs of Cincinnati.

Yet Merrill cites gaining early architectural influences intuitively from being exposed to the region’s abundance of 19th century buildings. Merrill fondly recalls working as a high school junior and senior in the small town of Glendale – a “railroad suburb” located north of the city.

“I liked the place so much that I was more than happy to drive a dump truck there in the summertime, or work on the brush truck – anything. Just being in Glendale was pleasant,” Merrill said. “I could walk through Glendale at this point and name all the late 19th century styles – I would appreciate it for very different reasons.”

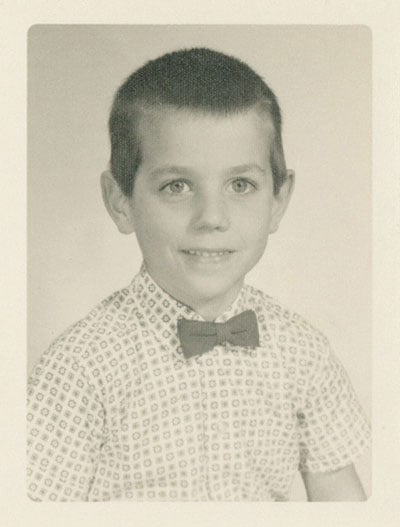

After graduating high school, Merrill shipped out to the University of Virginia and earned a bachelor’s degree in economics. Inspired by the university’s Thomas Jefferson-designed campus, Merrill found his interests shifting toward architecture and following graduation from UVA, he captained his beat-up Datsun 510 station wagon and embarked on a 2-year journey across the United States, absorbing the country’s various architecture styles as he traveled coast-to-coast.

Merrill (left) received a bachelor's degree in economics from the University of Virginia

“Within a period of a year and a half or so out of school it was generally my Jack Kerouac years,” Merrill said. “Whenever I had gas money and a little bit of free time I would take these trips. It didn’t matter whether you were in Richmond seeing the tobacco warehouses or if you were in New Orleans looking at shotguns – every part of the country has some kind of building culture that made it distinct from the rest of the country. I really learned to love the country.”

Merrill’s two years of nationwide wandering brought him many moments where he thought about the places he saw, what made them unique, and what made them the same. In 1982, Merrill enrolled in the Yale School of Architecture in New Haven, Connecticut and completed a master’s degree in architecture in 1984.

Fresh out of the Ivy League, Merrill set out to begin his professional career in Washington D.C. and got his feet wet with two architectural firms – McCartney Lewis Architects and Cass & Pinnell Architects.

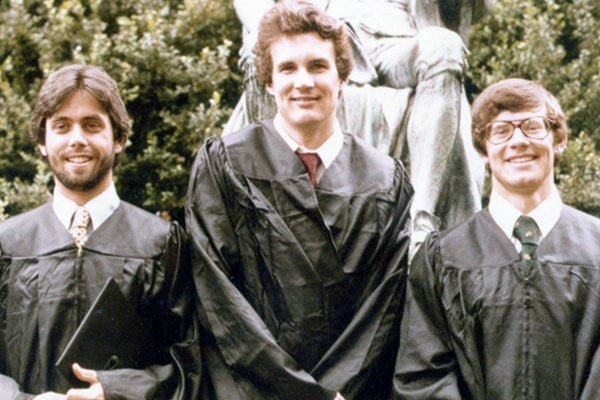

Grapefruit Country

Seaside, Florida. More than half it was undeveloped when Merrill arrived in 1988.

Photo Credit: Michael Moran

In the midst of making wedding plans with his soon-to-be-wife, Zo Anne, Merrill received what would prove to be a life-changing invitation in 1988 from developer Robert Davis to work with Florida-based urban planners, and New Urbanism pioneers, Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk of Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company (DPZ) as town architect in Seaside, Florida. Although initially reluctant to pack up and leave D.C. and for the southern, sunny shores of the Gulf Coast, Zo Anne encouraged Merrill and reassured him that he should see the opportunity through.

“There were a number of things that were, I would say, risky about that particular decision,” Merrill said. “When you’re young, you make sacrifices to go someplace where there’s more work. We were relocating to a part of the country where neither one of us had personal or familial roots. I was very concerned about the fact that there wasn’t – at that time – great healthcare, great schools. The first day we got there someone said, ‘Well, it’s not the end of the earth but you can see it from here.’”

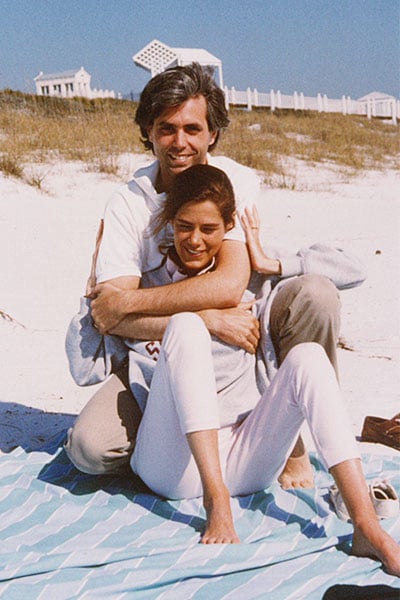

Merrill and wife Zo Anne in Seaside at Honeymoon Cottage site, 1988

Fostering DPZ’s New Urbanism values of density, modesty, example, and community, Merrill was assigned to design a row of beachfront rental cottages in Seaside now known as the Honeymoon Cottages, with consultation provided by world-renown architect, theorist and urban planner Léon Krier. Merrill would later help Krier build the University of Miami’s Perez Architecture Center – one of Krier’s few built buildings – and describes Krier as “a friend” and “a great source of encouragement.”

“One of the fun things about working with Léon was really helping him understand which way he had to face, so part of my job was to help Léon navigate,” Merrill explained. “The confidence that you get in encouragement from somebody who is already so well-established, is immense. He’s been sort of like a godfather for even the people who have been in the front ranks of, let’s say, the converse for New Urbanism. He is the one at whose feet even the leaders of that movement have learned.”

In 1990, Seaside was recognized as one of Time Magazine’s “Best of the Decade” designs and Merrill received a National American Institute of Architects (AIA) Award of Excellence for the Honeymoon Cottages – his first project as a sole practitioner.

Merrill, wife Zo Anne, son Will, and daughter Ella in White Rocks, VT, 2003

Scott's Hands

Following his early success at Seaside, Merrill and Zo Anne made the decision to stay in the Sunshine State and Merrill joined DPZ to work on Windsor, a private 416-acre, high-density neighborhood development located in Vero Beach. The project included the design and construction of the Windsor Town Center and several housing types, including the courtyard house, the sideyard house, and row houses.

Merrill launched his own practice in Vero Beach in 1990 and later expanded with the addition of partners George Pastor in 1997 and David Colgan in 1999 to found Merrill, Pastor & Colgan Architects. Colgan, who describes Pastor and himself as “Scott’s hands,” opened and currently operates the firm’s satellite office more than 500 miles away in Atlanta, Georgia.

In 2000, Merrill was presented with his second national AIA Urban Design Award for his first group of buildings – the Windsor Town Center – and the firm received a national AIA Design Award in 2004 for the Seaside Chapel, the firm’s first public building.

Also in 2004, the firm’s work was recognized as a whole with the Arthur Ross Award from the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art in New York. In 2012, Merrill was honored for his contributions to the Seaside community and awarded the Seaside Prize.

Considering “urban design,” “historic preservation,” “sustainability,” and “project management,” from small single-family homes to large urban site planning, the firm has designed projects all across various parts of the globe, including the United States, Canada, the Caribbean, England, Haiti, New Zealand, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Scotland, the United Arab Emirates, and more.

For more than 25 years the firm has operated with a primary interest on using land efficiently for developing buildings and site planning.

Merrill at his office in Vero Beach, Florida, 2016

Photo Credit: Chuck France

Driehaus Laureate

In January 2016, Merrill was announced as the recipient of the 2016 Richard H. Driehaus Prize at the University of Notre Dame. As the 14th Driehaus Prize laureate, Merrill will be awarded the $200,000 prize and a bronze miniature of the Choregic Monument of Lysikrates during a ceremony at the John B. Murphy Auditorium in Chicago.

“Scott Merrill has demonstrated how the principles of classicism can be used as a foundation for designing buildings that respond to and express regional character while employing the richness of precedents found throughout the ages, including our own,” said Michael Lykoudis, Driehaus Prize jury chair and Francis and Kathleen Rooney Dean of Notre Dame’s School of Architecture. “His applications of architectural forms from various times and places to modern settings are used to reinforce the values of community, beauty and sustainability without sacrificing economy.”

Merrill has lectured at Notre Dame, Yale, UC Berkeley, the Institute of Classical Architecture in New York and Chicago, the Houston Fine Arts Museum, and more, and has served on AIA juries for Pittsburgh, Washington, Austin, Mississippi, Arkansas, Florida, and the National AIA awards.

“‘Life is always right, the architect is always wrong,' I’ve heard it quoted a number of different ways." Merrill said, referring to modernist architect Le Corbusier’s comment about people altering his buildings after they lived there for a while. “We have our own formal preoccupations and to the degree that we try and force these personal preoccupations on the world, the world’s gonna push back. There is that tendency among all professions, so we tend to fight over things that are relatively unimportant and sort of miss the things that are worth contending or contesting. The best description of architecture is Flannery O’Connor’s description of fiction. She says, ‘Basically, it’s about everything human and we are made of dust, and if you scorn getting dusty, then it’s just not a grand enough job for you.’ I don’t know how any architect could describe our job any better than she could describe it.”