Jeff Maldonado

No one really knows how they will respond should their worst nightmare come to pass.

The first thing Jeff and Elizabeth Maldonado did was seek refuge. They couldn’t go home to Pilsen. The emptiness of their house – filled, as it was, with their son’s clothes, his music, his smell – just the thought was unbearable.

They left Stroger Hospital after Jeff Jr. died and checked into a hotel in the Loop. Those days were the darkest of their lives.

“Devastating barely scratches the surface,” said Jeff Maldonado Sr. “They were surreal, dreamlike…”

They cried. They slept. They discussed putting an end to their own lives.

“Just the thought of living without him – it was unimaginable.”

Their son was an innocent victim of Chicago’s gang violence. A gang member shot him while he was on his way home from the local barbershop, just one day after his nineteenth birthday. It was reportedly a case of mistaken identity. The man who fired the gun mistook Jeff Jr. for a member of a rival gang who had killed his father, also a gang member, the year before.

The crowd that gathered on the corner of 18th Street and Racine thought that he might make it. Blood ran down his face, and yet he had the strength to lift himself onto the gurney. He was conscious when the ambulance pulled away.

But by the time his parents arrived at Stroger Hospital, he was in a coma. The doctors said there was no way he’d make it.

Jeff Sr. walked up to his son and whispered in his ear, “The body dies, but the spirit lasts forever.” It was an attempt to comfort his son and himself.

At 8:20 p.m. on July 25, 2009, Jeff Jr. was pronounced dead.

---

His name wasn’t always Jeff. He was born Christian Devon Zepeda. When he came into the world on July 24, 1990, his parents weren’t together. His mother, Elizabeth, thought she’d have to raise him alone.

“I wasn’t even there when he was born,” Jeff Sr. says now, regretfully. “We were just kids ourselves.”

But he was very aware of his son’s existence. When Jeff Jr. was a baby, Jeff Sr. says his son came to him in dreams.

“He’d be like, ‘Where are you? I need you. Where you at?’” he says.

In their mid-20s, Jeff and Elizabeth reunited and decided to be a family. Their son was five years old. Jeff Sr. quickly got to work trying to earn his son’s trust.

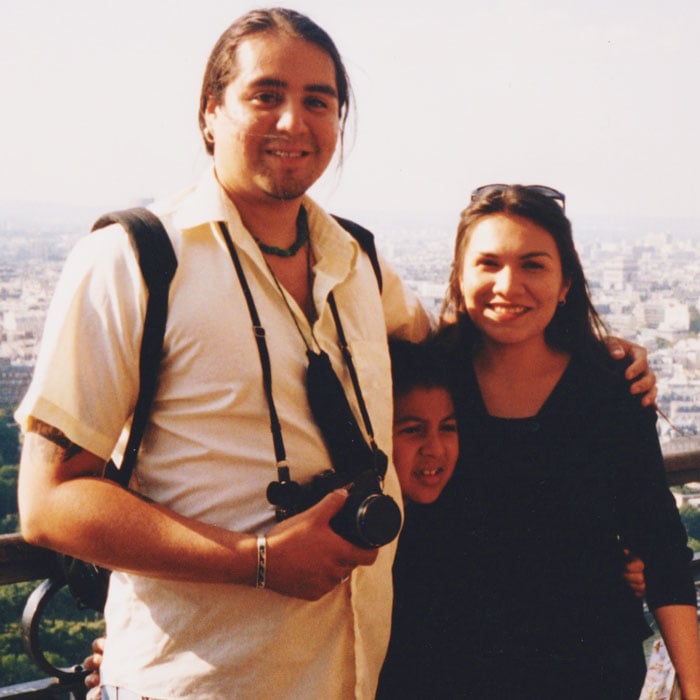

The Maldonado family on vacation. Courtesy of the Maldonado family

He had recently started teaching art classes to youth at The National Museum of Mexican Art.

“With the flexible schedule, I was able to pick up my son from school, drop him off, make him something to eat when he got home, help him with his homework,” he said. “When I had to teach a class, he’d come with me. He’d draw or paint or whatever.”

Jeff Jr. spent so much time making art, says Maldonado, he actually sold his first painting at age eight.

“Those were great times. A great time in our family history. Because everything was possible,” he says.

He says the “proudest moment” of his life took place when his son was ten. The two drove from Chicago all the way to San Luis Potosi, Mexico. His son got nervous a few hours outside of Chicago. He wanted his mom. But there was no turning back. The two were on their way to Jeff Sr.’s father’s hometown, to bury their father and grandfather.

By the time they got to the border, they were closer than they’d ever been. In San Luis Potosi, they visited with cousins and relatives who Jeff Sr. had seen only occasionally while growing up. They asked why his son had a different name.

“And not just a different name, but a very different name – Christian Zepeda.”

He suggested to his son that they change his last name to Maldonado. But the boy had another idea.

“He said to me, “I wanna be a junior. I wanna be Jeff Maldonado Jr.”

He shakes his head as he remembers it now.

“That was the proudest moment of my life.”

---

Jeff Sr. was close to his own father, and they had their rituals. Every Sunday morning, they’d head out to the old Maxwell Street Market. They’d get up and hit the road while it was still dark so that they could be among the first people there – the professional deal hunters. Young Jeff would rummage through comic books while his dad haggled over used tools.

“Dad was hard core,” Jeff says.

After Maxwell Street, they’d roll down 18th Street to pick up their Sunday morning staples: menudo, carnitas, tortillas –things they couldn’t get where they lived in nearby Bridgeport.

“We always moved around, but Pilsen was like our cultural center,” Jeff said. “And I always remember that drive because I remember the murals.”

That was the late 1970s, and Pilsen was the epicenter of the Chicano movement in Chicago. The muralists that have since made Pilsen famous were just coming of age; many of them were just finding their own styles. Most of those early works – featuring Aztec warriors, Mexican revolutionaries, and local heroes – are no longer visible, faded by the elements or destroyed by development.

To a comic book kid, those murals were shrines to a culture and a lifestyle he felt irrepressibly drawn to.

“I felt like it was a puzzle I had to figure out,” said Jeff. “It was a new language for me.”

His dad didn’t have much context for the images, and so it was a language that Jeff didn’t start acquiring until much later.

Instead, at a young age, he was pulled into less constructive pursuits. His parents soon got a divorce and he began bouncing back and forth between them. He became an angry young teen. He got into a lot of fights. He joined a gang in middle school, and in high school, he says, “It got real.”

He was expelled his freshman year and transferred to another school.

“I didn’t care because I was like, ‘My parents are getting a divorce. My home life is falling apart.’ I was angry and I wanted to have some kind of say in my own decision making.”

Maldonado was arrested repeatedly – for possession of an unlawful weapon, riding in a stolen vehicle – he can’t even remember how many times. He served some time in Audy Home, Chicago’s infamous detention center for juveniles.

At one point, a judge ordered him out of Illinois, so he went to live with his aunt and uncle in rural Texas. There was so little to do there that he started spending more time reading and sketching.

When he returned to Chicago, he stayed out of trouble and away from his old friends. He took night classes and worked part-time during the day.

One day while waiting for his dad at an old barbershop at 18th Street and Allport, he wandered across the street and into Prospectus Art Gallery, where he saw an exhibit of Mario Castillo’s work. Castillo was a pioneer of Chicago’s Chicano muralist movement.

“I remember asking the gallerist, ‘Who is this guy? This is incredible work.’”

The gallery owner told him that Castillo was teaching at Columbia College.

Jeff went back to the barbershop and told his father that he had made a decision: he was going to college.

Jeff Jr. was born right around the same time that Jeff began studying under Castillo. He immersed himself in his art, eventually getting a studio in the A.P.O. building on 18th Street. It was 1994 – the year the Jumping Bean Cafe opened across the street – and Pilsen was a scene. He spent his days painting and his nights partying.

“I felt like there was a chance here to follow what I wanted and make it real,” said Maldonado.

Pilsen was not a safe place to live. There was a different gang on every block in those days, and people got shot every other week. But Jeff says it was worth it just to rub elbows with his heroes – people such as Hector Duarte, Carlos Cortez, and Marcos Raya.

“You know, these are lions of Pilsen art,” he says. “I was right in the middle of everything, and I was young. It was exciting.”

He got a job teaching a summer program for kids at the Mexican Fine Arts Museum, now the National Museum of Mexican Art. Eventually, it turned into a full-time, year-round gig.

“It seemed like there were these unseen forces that were helping to guide me,” he said. “And it all had this connection to Pilsen, to 18th Street.”

Around the same time, he was reconciling with Elizabeth and becoming more involved in his son’s life. The two were married in 1995.

Jeff and Elizabeth did their best to create a nurturing, supportive, and open environment for Jeff Jr. They encouraged him to pursue his interests and tried to teach him to be kind, and true to himself.

Still, Jeff Jr. struggled academically when he entered Benito Juarez High School. Before his freshman year was over, Jeff Sr. ran into a friend at the Jumping Bean who helped Jeff Jr. transfer to Perspectives Charter School in the South Loop. The smaller class sizes, says Jeff Sr., “helped him be recognized for who he was.”

As his son got older, Jeff Sr. told him stories about the mistakes he had made as a teen.

“He loved hearing those stories about my past. He was kind of living vicariously. I said ‘I went through this stuff so you don’t have to, and I went through this stuff so I could teach you about it.’”

That didn’t mean he avoided trouble entirely. He became a graffiti artist and “dabbled in the street life,” his father says. He lost friends to violence, but he avoided joining any gangs himself.

Eventually, he found his voice in music. His good friend’s older brother was an emcee. When the big brother wasn’t around, the two would sneak into his room and record tracks. Jeff Jr.’s rhymes were full of his experiences and had a message of hope:

We need to work hard to make the world better

Stop killing each other and start coming together

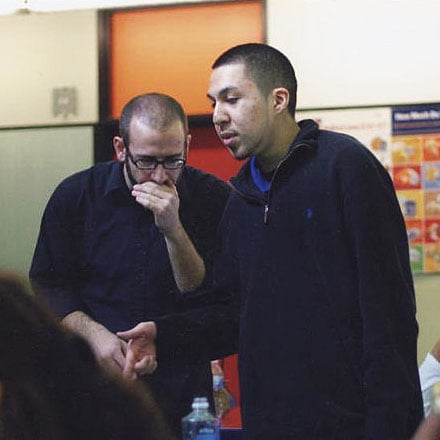

Jeff Jr. performing. Courtesy of the Maldonado family

“We were really convinced that he was going to make it professionally. And he was the pride and joy of the family,” says his dad.

“What was so heartbreaking about all of this experience is that he had a future.”

He was supposed to have his first public performance as an emcee on the day he was killed.

“So, in a blink of an eye, everything we worked for and everything that we sacrificed for and everything – it just disappeared,” says Jeff Sr.

---

When Jeff and Elizabeth traveled from the hotel in the Loop back to their home in Pilsen three days after their son died, they didn’t know what to expect – or how long they’d be able to hang on without him.

But as soon as they arrived back in Pilsen, they started feeling less alone. “J-Def RIP” was spray-painted everywhere.

“We didn’t even know that anyone else knew,” he said.

Jeff Jr.’s old high school guidance counselor was at the house almost immediately.

“And people didn’t stop coming. For days and days and days and days. Man, I mean – there was so much activity. Positive activity.”

Jeff Jr.’s friends were always there, sharing stories. One said Jeff Jr. encouraged him to go back to school. Another talked about how he was the kind of friend who was always there. They wanted to give back to his family. They organized a carwash on the corner where they used to hang out to help Jeff and Elizabeth pay for funeral expenses. They washed cars for four days and four nights.

“We were in such a bad place. And then, coming back to the neighborhood and seeing what his friends were doing, that was the lift we needed.”

“We were in such a bad place,” he said. “And then, coming back to the neighborhood and seeing what his friends were doing, that was the lift we needed.”

A month later, they organized a march for peace in Pilsen. Hundreds of people came out – poets, bikers, young anarchists, artists, old neighborhood activists. They marched along Jeff’s final route from the barbershop towards his home.

“It was for the community to vent, to release their frustration, to ask questions, and to care for each other,” says Jeff Sr.

Buoyed by a need to continue remembering his son, Jeff got to work creating a giant mural at his son’s former high school. He enlisted the help of 15 of Jeff Jr.’s old classmates.

“It felt great,” he said. “It was being proactive and sharing the story.”

After that project, people started asking what mural project he was planning next. So he found additional sites where he could continue to teach youth his son’s story and give them opportunities to express themselves through art.

“[There was] the need and the desire for this program to keep going and then to expand,” he said. “It was a testament to the need for youths to find some place that was safe, some place where they could gather, some place that nurtured them, nurtured their creativity.”

Through the project, he teaches youth about interpreting the artwork of others. He encourages them to develop skills in painting, drawing, and mosaics. The centerpiece of the project has always been the collective work of painting public murals.

Maldonado says he’s seen a shift in recent years away from promoting positive messages and towards what he calls “artists or muralists just promoting their own style.”

“This community is changing, and it’s evident by the type of murals being painted,” he explained.

He says part of his goal as an artist is to bring what he calls the “old-school mission” back to Pilsen street art.

In the past seven years, Jeff estimates that about 900 kids have been involved in the J-Def Peace Project. They’ve painted murals at Solorio High School, St. Procopius Church, and Dvorak Park. Their most vibrant and visible project was at 18th Street and Paulina, where Jeff’s portrait is affixed to the wall with mosaic tiles, surrounded by glimmering bits of mirrors.

Jeff Maldonado stands with the J-Def Peace Project mural. Photo by Kaitlynn Scannell

The program is slated for expansion. Jeff Sr. recently received funding to kick off a class in Back of the Yards.

As part of a separate endeavor, Jeff Sr. and Elizabeth have commissioned a short documentary about their son’s life and his message of peace. Jeff shows it to new students to help inspire their work and set the tone for the J-Def Peace Project.

"There are a lot of great programs in this city that work with youth. I think ours is unique."

“And I think that’s the power right there,” he said. “There are a lot of great programs in this city that work with youth. I think ours is unique. And what makes it unique is that there is a young man here who is just like a lot of other kids in this city, with all of this really great potential and a big heart and talent. And he’s identifiable as a role model.”

He tells the kids that picking up a gun is easy. The more difficult thing is changing the conditions and the mindset that allows things to come to that. That’s what he hopes to do for the J-Def Peace Project youth – introduce them to another way of thinking, being, and interacting with their community.

“I wish I had an outlet like this when I was young,” he says. “I was thirsty for that.”

Talking about Jeff Jr., sharing his story, also allows him to keep Jeff Jr. close. He loves when he sees his students connect with his son.

“I think now more people know about him now than ever,” he says.

Today, Jeff Maldonado feels grateful that he had Jeff Jr. in his life, even if it was for only nineteen years and a day. And he’s also grateful that he has found a way to continue nurturing creativity, compassion, and civic engagement in young people, much as he did with his son.

“I think, as a father, the only way I’ve been able to deal with this is to take that energy and create good with it.”

– Jessica Pupovac