Lilliana Calderon

The hum of generators filled the air as workers unloaded bricks from a beeping pick-up truck in Lincoln Park on a sunny and windy Chicago afternoon. Wearing cargo pants and an electric green and orange shirt, Lilliana Calderon walked through the construction site with ease. No more than 5'3", Calderon took off her white helmet, revealing cropped brown hair.

“I love this job,” she said. “I love working with my hands.”

Calderon pointed up to the eighth floor of a high-rise building. “That’s where I was laying brick yesterday,” she said.

Calderon has worked as a bricklayer with J & E Duff since 2008 and is a member of the International Union of Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers.

Calderon was the only woman working on the site.

Like a select few other women in Chicago, Calderon found steady employment and financial independence with the help of Chicago Women in Trades (CWIT), located in a large warehouse on the border of Pilsen and Little Village. Founded in 1981, its programs help women – particularly women of color -- enter plumbing, carpentry, pipe-fitting, electric, and bricklaying trades.

While gentrification continues to push out the most vulnerable residents of Pilsen and Little Village, CWIT helps low-income women of color gain financial independence and, in some cases, buy homes in the neighborhood.

Originally from the nearby neighborhood of Gage Park, Calderon was working at a bakery when she first attended a Chicago Women in Trades information session in 2006. Afterward, she said to herself, “Why not go through the training?”

Calderon took a test and qualified for the 10-week pre-apprenticeship program, which included math, physical activity, and exposure to different trades. She remembers coming out of her first weeks at CWIT with swollen wrists from the physical training. “I used to have real skinny forearms,” she said. “I remember telling my mom, ‘Can you rub my hands?’”

But when Calderon laid her first brick, she said, “It was love at first sight.”

Although more women are in the construction trades today than when the organization started back in 1981, women make up only 2.8 percent of all workers in the construction trades nationally, according to the 2016 Current Population Survey of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In Chicago, women make up 7 percent of the construction trades, said Linda Hannah, the technical opportunities director at CWIT.

“We’ve been doing this for 35 years, and we have seen so little progress,” said CWIT Executive Director Jayne Vellinga. “This is a problem beyond just the industry. This is a problem that starts in the family and when women go into school.”

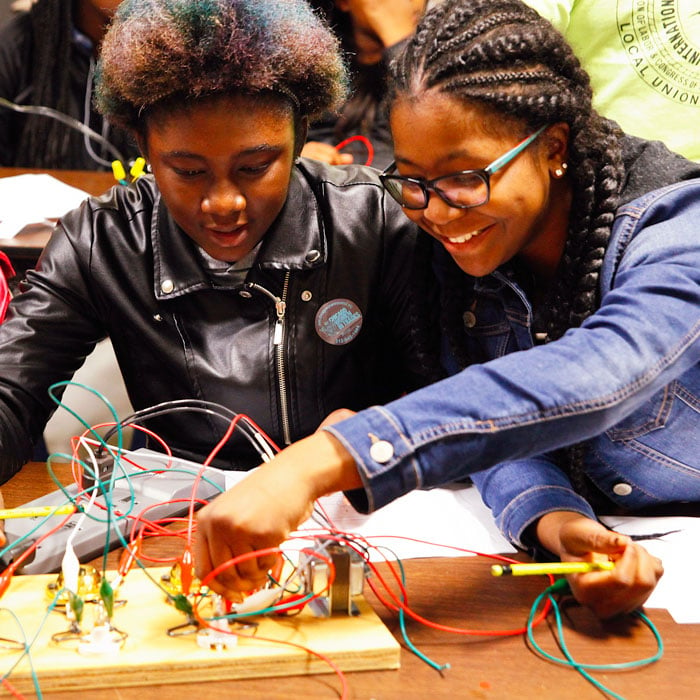

CPS students get hands-on training under the guidance of CWIT leaders in woodworking, welding, and wiring. Photos by Kaitlynn Scannell

From apprenticeships to the hiring and firing process, Vellinga and Hannah say the construction industry favors men.

“The construction industry is designed for an 18-year-old boy who can borrow his family’s car and go somewhere unpaid for ten weeks,” said Hannah. For an adult woman who has no vehicle or who has children, it is difficult.

Vellinga said women of color experience gender and racial discrimination in the hiring process and in maintaining jobs. “It is hard to tell what kind of discrimination you are facing. All you know is you didn’t get the job again or that you get laid off,” she said.

CWIT’s program is aimed at helping women enter the construction trades and stay in them. They have a room dedicated to physical fitness, where women carry 30 pounds across narrow wooden blocks. If women fail at their first attempt, they undergo training until they pass the test.

In 2016, 78 women completed the pre-apprenticeship program at CWIT, and 30 completed the welding program. From the initial group of 78, 68 women entered employment in the trades, according to Vellinga.

Two welding students practice side-by-side at CWIT headquarters. Photos by Kaitlynn Scannell

“We have a long way to go before women achieve real parity in this industry,” said Vellinga. In order to see more gains for women, Vellinga said there would likely need to be a shortage in the labor force. The construction industry itself is still recuperating from the economic crisis of 2008.

But with federal pressure to narrow the gender gap in construction, CWIT is positioned to increase the presence of women in the male-dominated field.

Just two months before the 2016 presidential election, Chicago Women in Trades received its first major federal contract since the organization was founded. As part of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission under the US Department of Labor, CWIT is scheduled to receive $7 million over five years to continue their programs.

Meanwhile, their program continues to support women who are seeking employment and economic independence and who are willing to put in the extra work. This includes encouraging women to continue applying even when they get rejected.

After eleven years in the industry, Calderon is at the top of her earning scale as a journeywoman. She sits on the board of CWIT and is her union delegate.

“It’s about giving back to your community,” she said.

She earns an estimated $80,000 per year and works an average of 30-35 hours per week. Two years ago, Calderon participated in a competitive statewide bricklaying contest. Contestants are expected to lay 500 bricks per hour. Calderon explained that in an 8-hour day, an average bricklayer lays 700 bricks. Calderon placed 6th and hopes to compete again this year.

Lilliana Calderon on a job site. Photo by Kaitlynn Scannell

“If you don’t love what you do, you won’t make it through,” she said. “This is fun.”

Calderon sat in her newly purchased three-story building in Pilsen with exposed brick behind her. She said she bought a home in Pilsen last year in order to be close to her best friend. Calderon and her fiancé like the community feel and enjoy seeing neighbors at the community bar down the street.

Calderon also recently purchased an investment property in Little Village. She spends her evenings remodeling that building.

– Cloee Cooper