Pilsen Environmentalists Organize to Protect Neighbors from Lead in Water

Troy Hernandez, data scientist and member of the Pilsen Environmental Rights and Reform Organization (PERRO), at the Clean Water Expo at Simone’s Bar in Pilsen on July 15, 2017. PERRO and JustDesign organized the event to distribute water filters and educate neighbors about the risk of waterborne lead.

All summer long, Magdalena “Lupe” Sedlacek’s four young grandchildren spend a lot of time outside her home, jumping rope, riding bikes, and dribbling the basketball on the sidewalk.

And when they come back inside, they drink a lot of water.

Sedlacek said she had no idea that there might be a problem with lead in her water until a recent Saturday afternoon, when neighborhood activists knocked on her door and told her that a water main replacement on her street may have caused lead levels to spike.

“It was shocking,” said Sedlacek. “I was absolutely surprised that all of this was going on and no one knew about it… No one is educated.”

Magdalena “Lupe” Sedlacek at PERRO’s Clean Water Expo at Simone’s Bar on July 15, 2017. Photo by Kaitlynn Scannell.

Three years ago, as part of a decade-long initiative to upgrade Chicago’s aging water infrastructure, crews with the city’s Department of Water Management (DWM) replaced what was then a 142-year-old water main in front of Sedlacek’s home on Morgan and 19th Street.

A 2013 EPA study found that disturbances like these can jostle the protective coating on lead service lines, which carry water from the water mains to thousands of Chicago homes, and cause lead levels at the tap to spike.

“As the ultimate human and environmental health goal, [lead service lines] should be completely removed where possible,” the study concluded.

In 2009, Chicago Department of Water Management crews and contractors launched a massive initiative to install more than 100,000 water meters and replace more than 90 miles of water mains; activists charge they’ve done so without giving hundreds of thousands of Chicago residents the information they need to help protect themselves and their families from potentially harmful lead levels.

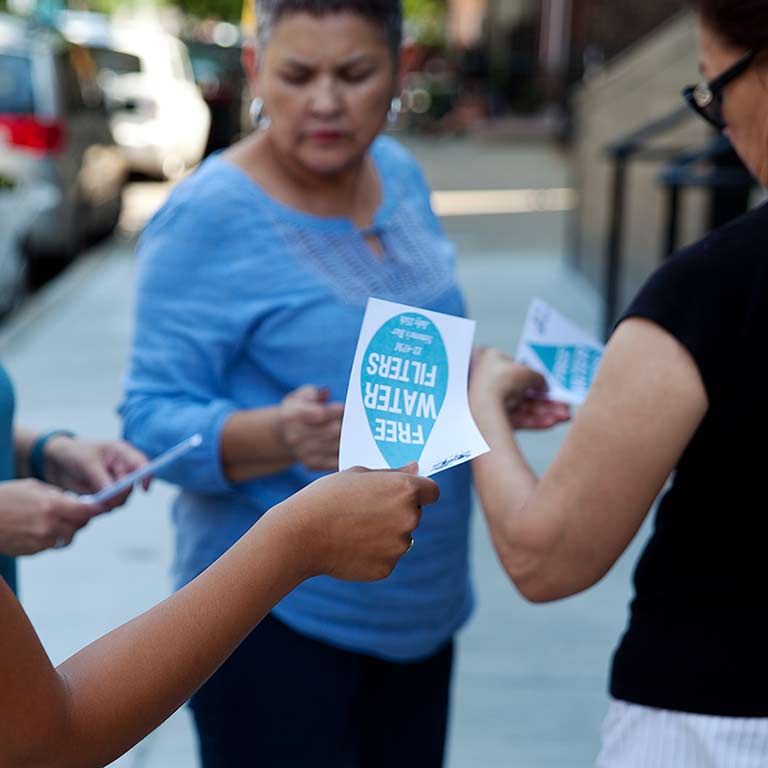

In June, the Alliance for the Great Lakes Young Professional Council awarded PERRO, the Pilsen Environmental Rights and Reform Organization, and JustDesign, a Chicago-based design cooperative, a $5,000 grant to purchase water filters certified for lead removal. They are knocking on doors where water main replacements have recently taken place and holding events to help provide Pilsen residents with tools and information that they hope will protect them from ingesting water contaminated with lead.

Jack Ailey of PERRO shows Maria Arriaga and her children how to install a faucet-mounted water filter. Photo by Jessica Pupovac.

Pilsen residents talk to a volunteer with the Alliance for the Great Lakes Young Professional Council at PERRO’s Clean Water Expo at Simone’s Bar on July 15, 2017. Photo by Jessica Pupovac.

Volunteers distribute information about PERRO’s Water Expo on 18th Street in Pilsen. Photo by Kaitlynn Scannell.

The Centers for Disease Control and the Environmental Protection Agency both say there is no safe level of lead exposure. Lead is a known neurotoxin that can do permanent damage to developing brains. When young children are exposed, it can lower their IQs and increase their risk of developing attention and behavioral problems such as aggression later in life. In adults, low-level lead exposure can cause kidney problems and high blood pressure.

Regulators and public health officials have spent decades phasing lead out of paint and other common household products. But in much of the Midwest, miles of lead service lines remain underground and out of sight, carrying water from water mains to individual houses. According to the Chicago Department of Water Management, approximately 80 percent of Chicago homes draw their water from lead service lines, in part because a city ordinance required lead service lines be used for new service connections until 1986, when the federal government banned the use of lead. While many homes might also have lead in solder or plumbing fixtures, service lines have the highest lead content and the greatest surface area and, thus, are the main contributor to waterborne lead.

In Chicago and other cities where lead lines are present, water utilities add anti-corrosive chemicals to the water to build up a protective coating on lead pipes and slow the release of the toxic metal. The recent crisis in Flint, Michigan, began when water officials failed to add such agents and sent highly corrosive water out into lead pipes.

But experts say that even when the proper additives are used, they can slow lead leaching, but they can’t stop it entirely. The toxic metal seeps from aging pipes whenever water sits stagnant for more than six hours. Tiny particles can also fall off whenever something jostles the pipes, such as nearby construction. According to a 2013 EPA study, when coupled with low water use, lead levels can remain elevated for years after such construction.

For these reasons, civil engineer Marc Edwards, the Virginia Tech professor who helped document and respond to the crisis in Flint and earlier in Washington, DC, calls lead service lines “ticking time bombs.”

“I could never rest easy with lead pipes in front of my house,” he said.

There are precautions people can take to reduce lead levels in their water — if they know they are at risk.

The American Water Works Association, a trade group of water utilities, scientists, and regulators, recommends flushing pipes for “at least 30 minutes” following water main construction — far longer than the five minutes recommended by Chicago officials. In their guidance for water utilities, they also suggest sharing information on the health risks of lead exposure, the benefits of lead-certified home water filters, and language identifying particularly vulnerable populations, namely pregnant women and children under the age of six.

Chicago’s communications make no mention of these issues.

The DWM protocol is to issue two notifications to residents — once before main construction and a second time immediately following — with instructions to flush their pipes for “at least five minutes.”

But activists with the Pilsen Environmental Rights and Reform Organization, or PERRO, say that information is incorrect, insufficient, and not reaching many vulnerable populations. They are working to bridge what they see as a dangerous information gap by knocking on doors, holding events, and distributing the tools and information that they say the city ought to be sharing with residents.

“We know that Chicago has lead pipes. We know that construction disturbs those lead pipes,” said Troy Hernandez, a data scientist and the current director of PERRO. “And if the mayor and the aldermen aren’t going to tell people that there’s a problem, then we’ll have to solve it ourselves, unfortunately. And so the way we can do that is by educating people and giving them lead-rated water filters so that we can get the lead out.”

Several cities — including Milwaukee and Madison, Wisconsin — are in the midst of long-term, city-sponsored campaigns to replace lead service lines because of the risks they pose to residents. City leaders in Milwaukee made the decision after their own tests discovered elevated lead levels in homes immediately after main replacement. They suspended Milwaukee’s ongoing main replacement projects at the time, calling them an “unacceptable and involuntary risk to the public.”

Members of PERRO and JustDesign hope that the City of Chicago will one day invest in a similar response.

"How much would it cost to remove the lead service lines in Chicago? A billion? Maybe more?"

“Chicago is definitely behind the curve on this one,” said Michael Tboris, a water researcher at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. “But in the absence of a crisis, I don’t think top-down solutions are likely to materialize, mainly because of expense and there’s no real pressure to do it. How much would it cost to remove the lead service lines in Chicago? A billion? Maybe more? If you ask people about that, they will say, ‘Look, if we’re going to spend a billion on something, is that the best way to use that? Is it bigger than the risk of other things that we might spend a billion dollars on? That’s a real calculation.”

Hernandez recognizes that replacing lead lines would be a massive undertaking, but he thinks that it would be worth the cost.

“People are genuinely concerned about the water they are giving their kids,” he said. “We can’t just throw our hands up in the air… That’s not acceptable.”

Hernandez is planning to replace his own lead service line, which carries water to his home in Pilsen. He’s says he’s gotten a few different quotes between $17,000 and $20,000.

“I do hope to have kids, so I have to do this,” he said. “And I think anybody who has small children should replace their lead service line.”

He recognizes that not everyone can afford it. That’s one reason why, in the meantime, he believes it is crucial that people are aware of other ways to reduce their risk of exposure.

He calls the city’s public information campaign “an anemic response.” The water main in front of his home was replaced in 2012, he said, and the only warning he claims to have received was a letter left in his neighbor’s door, which made no mention of lead.

“I lived in the coach house,” he said. “Had I not randomly gone to the front door, I wouldn’t have even seen it.”

Regardless, he says, the guidance was insufficient.

Tiboris concurs. “You have to provide them with more than the information,” he said. “You have to provide them with information on what that actually means and what they can do about it.”

But the DWM refutes claims that construction work elevates lead levels. They have a different interpretation of the EPA’s 2013 study, which was designed to assess the effectiveness of the EPA’s water sampling protocol, and just happened to discover a difference in lead levels in homes where the lines were disturbed.

“[It] was not originally designed to assess the effects of water main replacements and water meter installations on residential lead levels,” wrote the DWM spokesman Gary Litherland. “For example, the study did not sample homes before the main replacement or meter installation began, to provide a reliable “baseline” lead level.”

He also said that the study didn’t take into account other factors — such as the age of homes — that may have increased the risk of lead in the water.

“Moreover, the size of the study was itself too small to draw meaningful conclusions,” he wrote.

The city has since initiated its own study — the “largest study of its kind ever conducted,” according to Litherland — to thoroughly investigate any risks posed by water main replacement and water meter installation. That study will be completed in approximately two years.

Meanwhile, more than 611,000 feet of water mains are scheduled to be replaced in Chicago in 2017 alone.

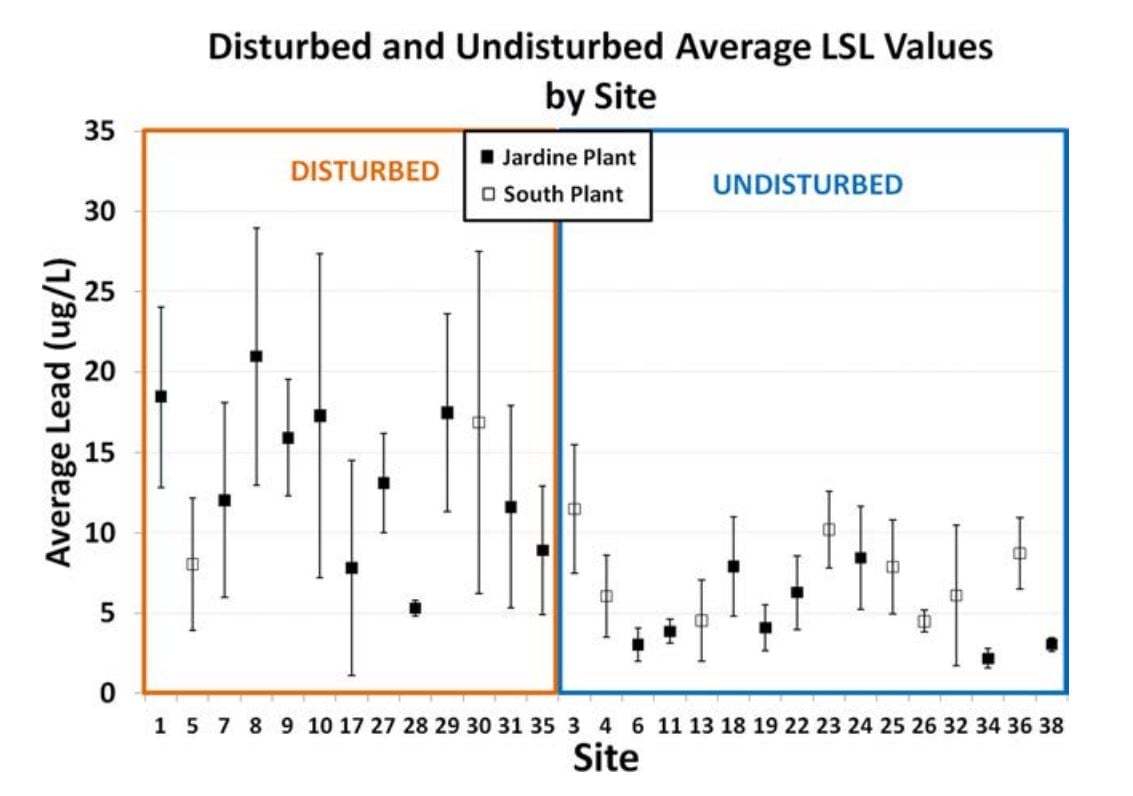

Hernandez says the EPA’s findings, should be enough evidence to inspire greater precautions. Researchers found high lead levels in 93 percent of the homes where there had been a recent disturbance to their lead service line. In homes where there had not been a recent disturbance, 19 percent of the homes had high lead levels in their water.

A 2013 study found higher lead levels in homes with disturbed lead service lines. Source: EPA study, as published in Environmental Science and Technology.

“Meanwhile, in the short term, people are drinking water with elevated lead levels,” said Hernandez.

Some Chicago residents have taken legal action to try to force the city to bolster its response. In February 2016, attorneys at Chicago law firm Hagens Berman filed a class-action lawsuit, calling the city’s lack of public notification “negligent and reckless.”

One of the plaintiffs, Tatjana Blotkevic, said her husband Yuriy Ropiy experienced heart attack-like symptoms during and after the city conducted a construction project near their home.

“We trusted the city,” Blotkevic said. “It’s the kind of thing you just assume — that your tap water is safe to drink and that your city has done its due diligence to prevent a health hazard like toxic levels of lead.”

The suit calls for a trust fund to pay for medical monitoring of lead-exposed residents and damages, including the replacement of lead service lines disturbed by city construction projects.

In the meantime, Pilsen residents near Wood, 22nd Place, and 23rd Street received a letter in their mailboxes in July 2017 informing them of imminent plans to replace 1,200 feet of water main along their streets.

The Chicago Department of Water Management advises residents to flush pipes for “at least 5 minutes” following water main construction. The American Water Works Association, a water utility trade group, recommends an initial 30-minute flush.

The second page of the letter instructs residents to flush their pipes for at least five minutes immediately following connection of their service lines to the new main. It does not mention the risks of not doing so, the health effects of lead, or the use of water filters.

The DWM says an additional notice — repeating the need to flush pipes for five minutes — will be distributed as the lines are reconnected.

Members of PERRO and JustDesign plan to knock on doors there and elsewhere to provide water filters to residents, and share what they consider to be more comprehensive information on how to protect themselves.

— Jessica Pupovac, August 1, 2017