Africa's Global Objects: Cécile Fromont at the Art Institute

Daniel Hautzinger

February 27, 2017

Cécile Fromont is fascinated by objects. An Assistant Professor of Art History at the University of Chicago who appears in Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s new, three-part documentary Africa’s Great Civilizations, Fromont is able to discern vast and varied layers of meaning in a cultural artifact. Wandering through the African Gallery of the Art Institute of Chicago, she hones in on a sculpture, painting, or ritual object, her eyes lighting up as she relates its story with infectious enthusiasm and an instinctive knack for teaching.

Fromont with Henry Louis Gates, Jr. at the Fortaleza de São Miguel. (Courtesy of Cécile Fromont) A late 17th century Ethiopian triptych reveals a connection to Italy and early Christianity in its depiction of a Virgin and Child that reinterprets an image, often attributed to St. Luke, residing in a Roman basilica. The scale, positioning, and iconography of a king and his wife or mother in a carved veranda post by Olowe of Ise demonstrate the power of women in the Yoruba hierarchy. A boli, or ritual object, of the Bamana people, reserved for the sight of only a select group, is indicative of spiritual practices and beliefs, but also raises questions about the public display of a sacred item.

Fromont with Henry Louis Gates, Jr. at the Fortaleza de São Miguel. (Courtesy of Cécile Fromont) A late 17th century Ethiopian triptych reveals a connection to Italy and early Christianity in its depiction of a Virgin and Child that reinterprets an image, often attributed to St. Luke, residing in a Roman basilica. The scale, positioning, and iconography of a king and his wife or mother in a carved veranda post by Olowe of Ise demonstrate the power of women in the Yoruba hierarchy. A boli, or ritual object, of the Bamana people, reserved for the sight of only a select group, is indicative of spiritual practices and beliefs, but also raises questions about the public display of a sacred item.

And these objects all fall outside Fromont’s specific research area. She specializes in the visual, material, and religious culture of the Portuguese-speaking Atlantic world during the early modern period (i.e., Angola, Congo, and Brazil from roughly 1500 to 1850). Much of her work examines the distinctive material and religious culture that emerged in Central Africa as it interacted with global trade and Christianity (Her first book is called The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo).

At the Art Institute, she refers to a Nkisi Nkondi from the Republic of the Congo. A humanoid “power figure” used against enemies and traitors, it contains symbolic materials and is activated for each use by driving metal into it. “Look at the nails driven into it and the mirrors in the eyes,” Fromont says. “Those are European-made. This is a global object and a testament of cross-cultural conversation.” It is evidence of the vital participation of Africans in world trade as both consumers and producers.

(Courtesy of Cécile Fromont)Such equal interaction is part of what interests Fromont in the early modern period. During this era, before the devastation and forestalled development of colonialism, Africans were shared inhabitants of an emerging modernity with Europeans. For instance, certain types of luxury textiles were produced in Europe specifically to meet African demand. Similarly, European missionaries sent to the Central African kingdom of Kongo in the late 17th century encountered a nation that was already strongly Christian, albeit with its own idiosyncrasies stemming from its own history and mythology. “The missionaries made explicit comparisons to the countryside of Italy” regarding the status of Christianity in the Kongo, Fromont says.

(Courtesy of Cécile Fromont)Such equal interaction is part of what interests Fromont in the early modern period. During this era, before the devastation and forestalled development of colonialism, Africans were shared inhabitants of an emerging modernity with Europeans. For instance, certain types of luxury textiles were produced in Europe specifically to meet African demand. Similarly, European missionaries sent to the Central African kingdom of Kongo in the late 17th century encountered a nation that was already strongly Christian, albeit with its own idiosyncrasies stemming from its own history and mythology. “The missionaries made explicit comparisons to the countryside of Italy” regarding the status of Christianity in the Kongo, Fromont says.

Africa’s Great Civilizations also reveals an obscured narrative, that of the history of the diverse peoples of Africa and their contributions to the world. Fromont is one of numerous luminaries, such as the Nobel Prize-winning Nigerian author Wole Soyinka and the paleoanthropologist Richard Leakey, who help “frame the narrative,” as she describes it.

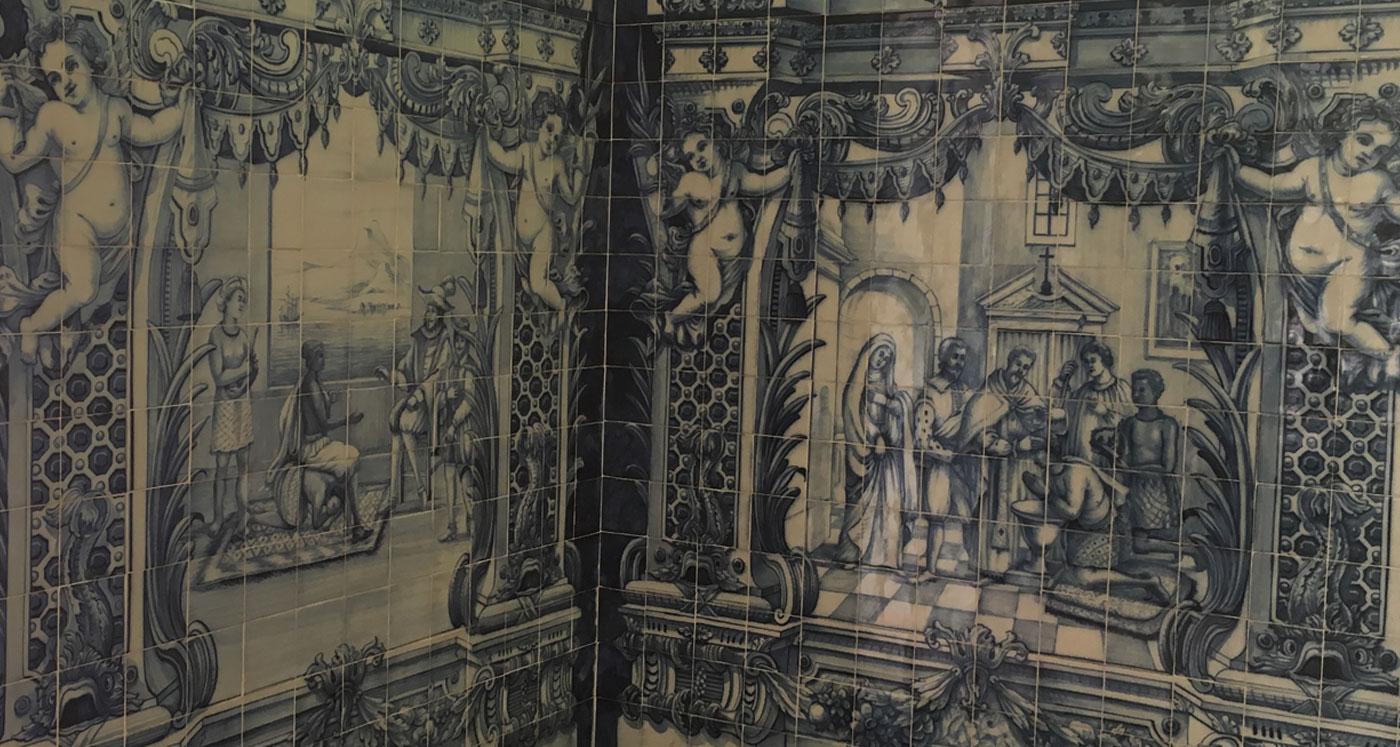

In the series, she appears at the Fortaleza de São Miguel in Luanda, the capital of Angola. A fortress built by the Portuguese, São Miguel contains ornate tiles that depict the history of Angola, and Fromont uses those to help narrate the story of the legendary Queen Njinga. Njinga was a 17th century monarch and diplomat of the Ndongo and Matamba kingdoms who has become a larger-than-life symbol in Angola for her diplomatic acumen and resistance to the Portuguese.

Njinga visited the fort several times as a prisoner, hostage, or envoy. Nor was she the only African to transit through Luanda in the shadow of São Miguel, the town being a major point of departure for slaves sent to the Americas.

The Portuguese slave trade between Central Africa and the Americas, specifically Brazil, is what originally led to Fromont’s research in Africa. She had always known she wanted to be an art historian, but went to school for political science after growing up in France. She took an internship in the French consulate in Brazil and quickly realized that a life in politics was not for her, so she applied to graduate school for art history, and eventually received her doctorate from Harvard.

Tiles at the the Fortaleza de São Miguel depicting Queen Njinga and other parts of Angolan history. (Courtesy of Cécile Fromont)She was originally interested in researching primarily Afro-Brazilian religious culture, but soon began “pushing back the timeline” to the origins of much of that culture in Angola and Kongo, in order to better understand it.

Tiles at the the Fortaleza de São Miguel depicting Queen Njinga and other parts of Angolan history. (Courtesy of Cécile Fromont)She was originally interested in researching primarily Afro-Brazilian religious culture, but soon began “pushing back the timeline” to the origins of much of that culture in Angola and Kongo, in order to better understand it.

“Forty percent of slaves in Brazil came from the Central African region,” she says. “Some of those slaves were actually already Christians when they were sent to Brazil.” Thus, a unique culture emerged that combined African, Brazilian, and Christian elements, one that provided a link between the two sides of the Atlantic. “Brazil and Portuguese-speaking Central Africa are not separate, but instead can be understood as part of the same broad area,” she explains. “You can fill a gap in the background of Afro-Brazilian art and religious culture by looking at Central Africa.” Just another way in which Fromont proves Africa was an integral part of global interactions in the early modern period, affecting and shaping the rest of the world.