"A Universal Jurisdiction Over Genocide": The Trial of Adolf Eichmann

Daniel Hautzinger

March 27, 2017

On Tuesday, March 28 beginning at 8:00 pm, the three-part series Dead Reckoning: War & Justice examines the evolution of justice in the prosecution of crimes against humanity since World War II, including the trial of Adolf Eichmann.

“Medium-sized, slender, middle-aged, with receding hair, ill-fitting teeth, and nearsighted eyes”: this is how Hannah Arendt describes the man whom she memorably characterized as illustrating the “banality of evil.” Adolf Eichmann was a major architect of the Holocaust, during which Nazi Germany brutally murdered some six million Jews and other groups deemed unfit to live by the Nazis.

Adolf Eichmann in Nazi uniform, 1940s. (Yad Vashem)On June 1, 1962, six months after being sentenced to death in a five-month trial held in Israel, Eichmann was hanged, the only person in the history of the country to receive the death penalty. “The long-term legacy of the Eichmann trial, first and foremost, is that it created a universal jurisdiction over genocide,” says Kelley H. Szany, the Director of Education at the Illinois Holocaust Museum in Skokie, which is currently presenting an exhibition titled “Operation Finale: The Capture and Trial of Adolf Eichmann,” through June 18.

Adolf Eichmann in Nazi uniform, 1940s. (Yad Vashem)On June 1, 1962, six months after being sentenced to death in a five-month trial held in Israel, Eichmann was hanged, the only person in the history of the country to receive the death penalty. “The long-term legacy of the Eichmann trial, first and foremost, is that it created a universal jurisdiction over genocide,” says Kelley H. Szany, the Director of Education at the Illinois Holocaust Museum in Skokie, which is currently presenting an exhibition titled “Operation Finale: The Capture and Trial of Adolf Eichmann,” through June 18.

“The trial set the precedent that perpetrators exist,” Szany continues. “Whether you’re a top official or an administrator, you’re not going to continue to commit these crimes with impunity, and eventually you will be held to trial.”

“Operation Finale” explores the capture of Eichmann in Argentina by the Mossad, the Israeli Secret Intelligence Service, and his subsequent televised trial. The exhibition includes artifacts from the Mossad archive, and was organized in Israel before being adapted for five American museums.

Eichmann’s defense against charges of crimes against humanity boiled down to this: “I was just following orders.” This is what Arendt meant by the “banality of evil": to her, Eichmann was completely unexceptional, a man who committed awful crimes not out of ideological hatred but simply because he was unthinkingly functioning within a bureaucracy. She set forth this idea, now disputed, in articles for The New Yorker covering Eichmann’s trial, later published as Eichmann in Jerusalem.

“Arendt wasn’t at very much of the trial, and had a lot of contextual historical misunderstanding of the Holocaust, and she made some mistakes,” says Szany. “But what she and the legacy of the trial did is allow us to look at the concept of the defense of ‘I was just following orders,’ which has been used more recently as well, for instance by a lot of the top leaders of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. What we now know is that Eichmann could have said no, but chose otherwise. The trial allowed us to examine the psyche and the social consequences of totalitarianism, and the role of perpetrators, of compliance, of following orders.”

The Eichmann trial, through its globally televised broadcast, also served as a watershed moment in Holocaust consciousness. “It really brought forth a global awareness of what the Holocaust was, and the atrocities that had been committed,” Szany explains. “The Holocaust became a history for more than just the Jewish community.”

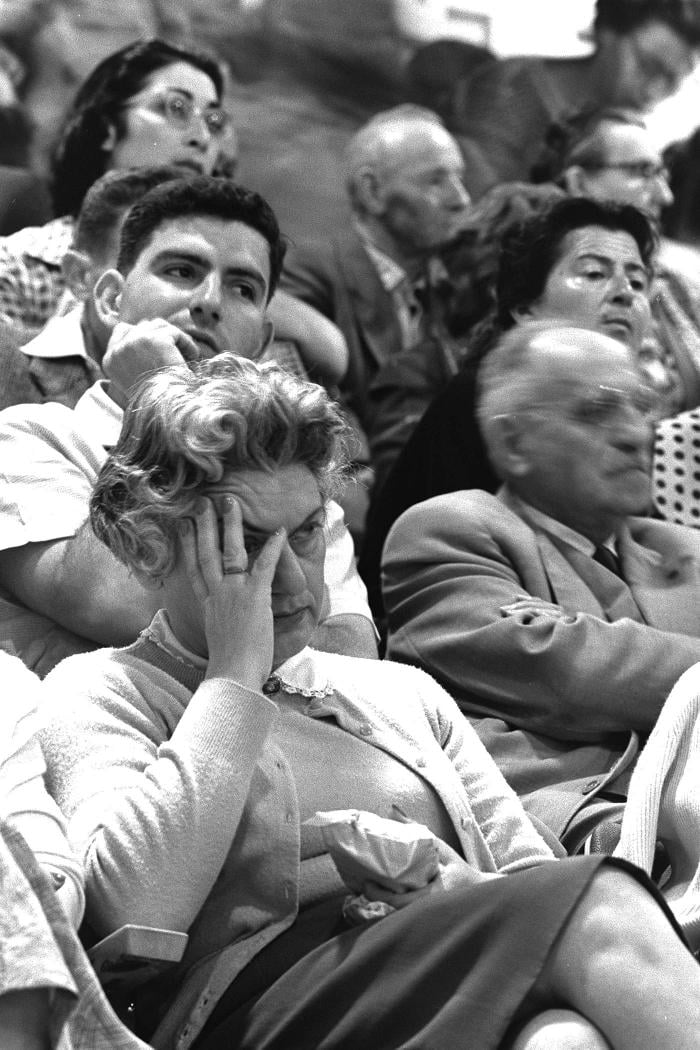

Spectators at Adolf Eichmann's trial, 1961. (Government Press Office)Although the Nuremberg trials, which prosecuted prominent Nazis for war crimes in 1945 and 1946, partly revealed the Holocaust, they focused on documents as evidence rather than personal testimony. Additionally, genocide was not part of the indictment, as it was for Eichmann.

Spectators at Adolf Eichmann's trial, 1961. (Government Press Office)Although the Nuremberg trials, which prosecuted prominent Nazis for war crimes in 1945 and 1946, partly revealed the Holocaust, they focused on documents as evidence rather than personal testimony. Additionally, genocide was not part of the indictment, as it was for Eichmann.

“What was different about the Eichmann trial was that it wasn’t so much about the documents, it was about the testimonies of the survivors,” says Szany. “You had 100 Holocaust survivors testify, some of whom had really no connection to Eichmann at all, but for the very first time told their stories. It was a catalyst for survivors to begin to speak about their own experiences.

“After the trial, we began to see a lot more memoirs and books and movies, we saw people beginning to consider how they could memorialize and educate and create museums about the Holocaust.” West Germany in particular began to reckon with the terrible crimes of the former German regime. The Holocaust began to be incorporated into West German school curricula, more Nazi war criminals were prosecuted, and intellectuals started to interrogate the dark German past – previously kept in silence.

Szany especially emphasizes a human consequence of the trial: how it helped survivors of the Holocaust reckon with the past. “I know a lot of the survivors here in the Chicago area really put their thumb on this trial as a formative moment in deciding that they needed to start to tell people more, to talk more, not only for their own catharsis, but to let their family and their community know about what happened.”