America Hears Itself

Daniel Hautzinger

May 16, 2017

The three parts of American Epic air and are available to stream at 9:00 pm on May 16, 23, and 30. The American Epic Sessions air Tuesday, June 6 at 9:30 pm.

In the late 1920s, American record companies began sending engineers across the country to capture the performances of home-grown musicians on wax. The record men lugged the newfangled Western Electric recording system with them, setting up in warehouses and calling for auditions from whoever could play a tune. The only requirements were that you brought your own song and that the performance was no longer than three and half minutes. The first stipulation was so that the record company could buy the publishing rights to sell it, the second was because the recording machine could only run for that long. The resulting records changed music forever.

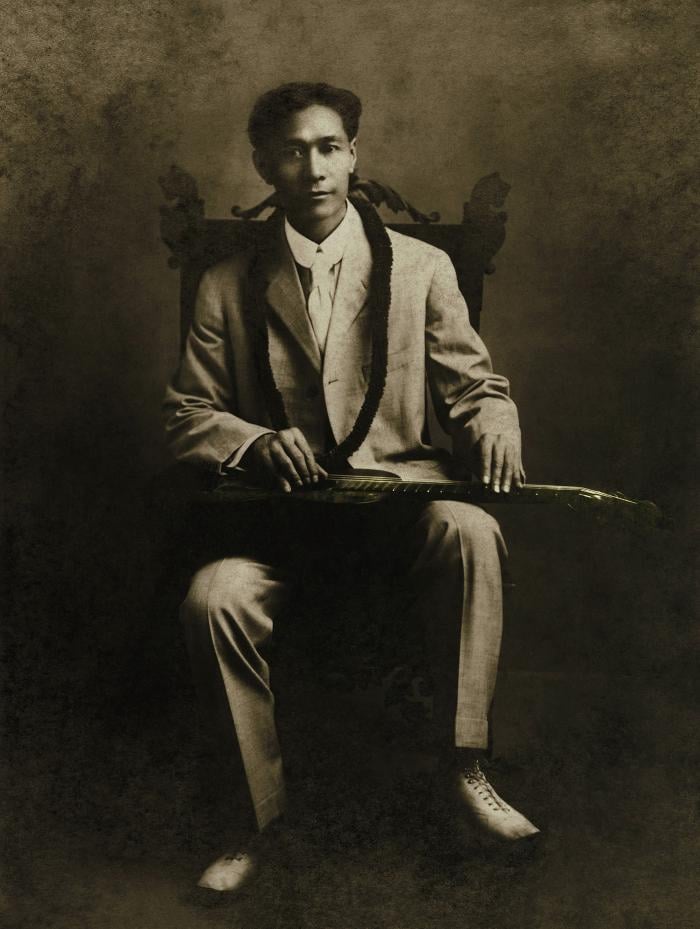

Joseph Kekuku, inventor of the steel guitar. Photo: Maida Vale MusicThe three-part film American Epic, narrated by Robert Redford, explores the stories of some of those diverse early recorded musicians, while The American Epic Sessions recreates those recording sessions by filming contemporary musicians as they record on a rebuilt Western Electric machine for an album produced by Jack White and T Bone Burnett.

Joseph Kekuku, inventor of the steel guitar. Photo: Maida Vale MusicThe three-part film American Epic, narrated by Robert Redford, explores the stories of some of those diverse early recorded musicians, while The American Epic Sessions recreates those recording sessions by filming contemporary musicians as they record on a rebuilt Western Electric machine for an album produced by Jack White and T Bone Burnett.

From the beginnings of country music with The Carter Family, to the invention of the steel guitar by Joseph Kekuku in Hawaii, to the emergent Cajun music of the Breaux Frères, American Epic illuminates foundational figures in American popular music. American Epic director, producer, and writer Bernard MacMahon first discovered these early records after hearing numerous musicians cite them as influences, from Ray Charles to Bob Dylan to the Grateful Dead.

“I think the first person I checked out was Mississippi John Hurt,” a legendary Delta blues artist, MacMahon recalls. “I was just completely spellbound by it because there seemed to be nothing between me and the performer. There was just directness about it. I think that’s because in these first recordings, there’s no concept of being a star. It’s just someone performing in the way they would perform on their stoop. There’s this honesty and purity.”

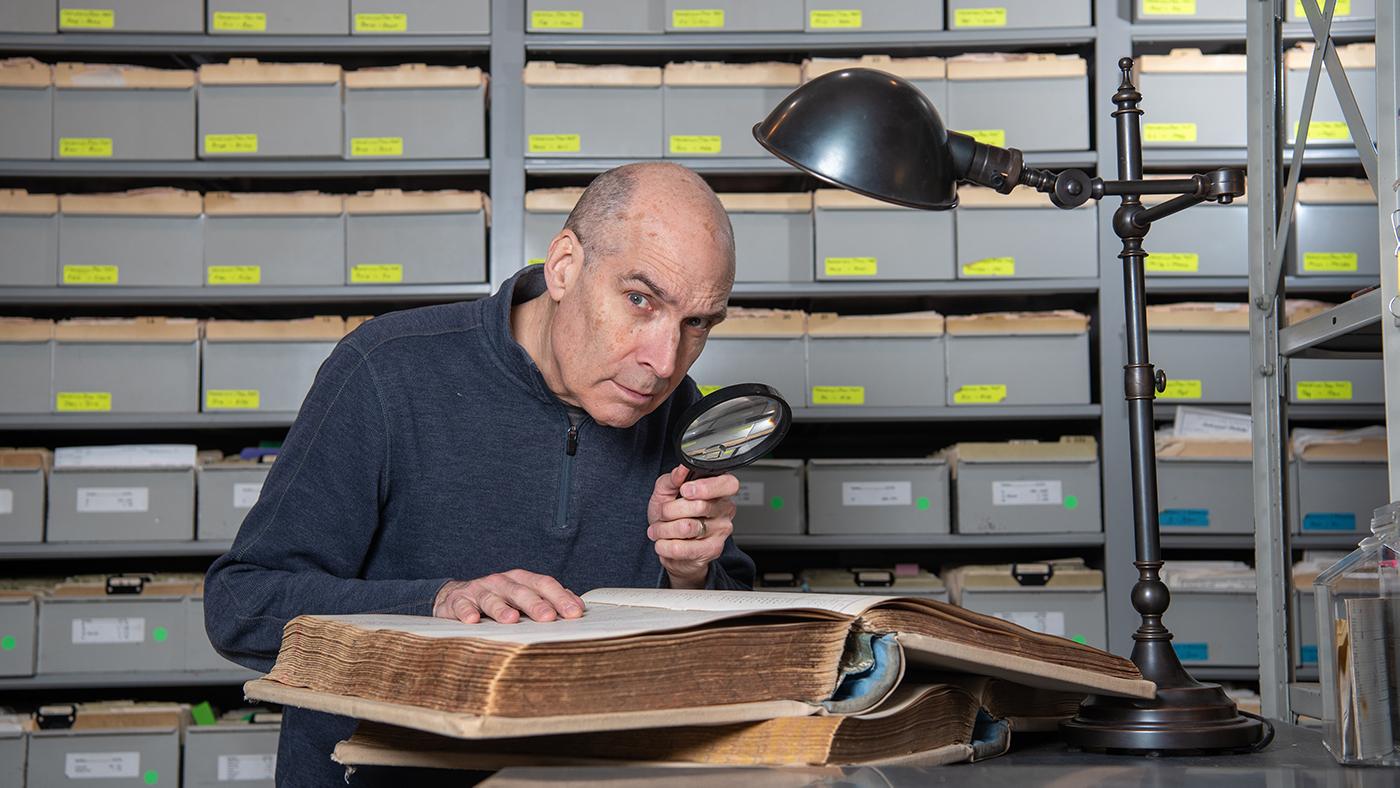

Legendary bluesman Mississippi John Hurt. Photo: Getty ImagesAs he dug further into the catalog of records from the 1920s, MacMahon began to notice that little was known about many of these artists, despite their legacy. He began scouring archives and placing ads in newspapers to find links back to musicians like the West Virginia miner Dick Justice, about whom nothing was known but his job and the region he came from.

Legendary bluesman Mississippi John Hurt. Photo: Getty ImagesAs he dug further into the catalog of records from the 1920s, MacMahon began to notice that little was known about many of these artists, despite their legacy. He began scouring archives and placing ads in newspapers to find links back to musicians like the West Virginia miner Dick Justice, about whom nothing was known but his job and the region he came from.

After finally connecting with Justice’s elderly daughter, he discovered that two other “epochal” folk musicians had worked in the same mine: Irving Williamson and Frank Hutchison. At that point, he knew he had to tell these stories before the last connections to them disappeared with the death of family members and friends who had firsthand knowledge.

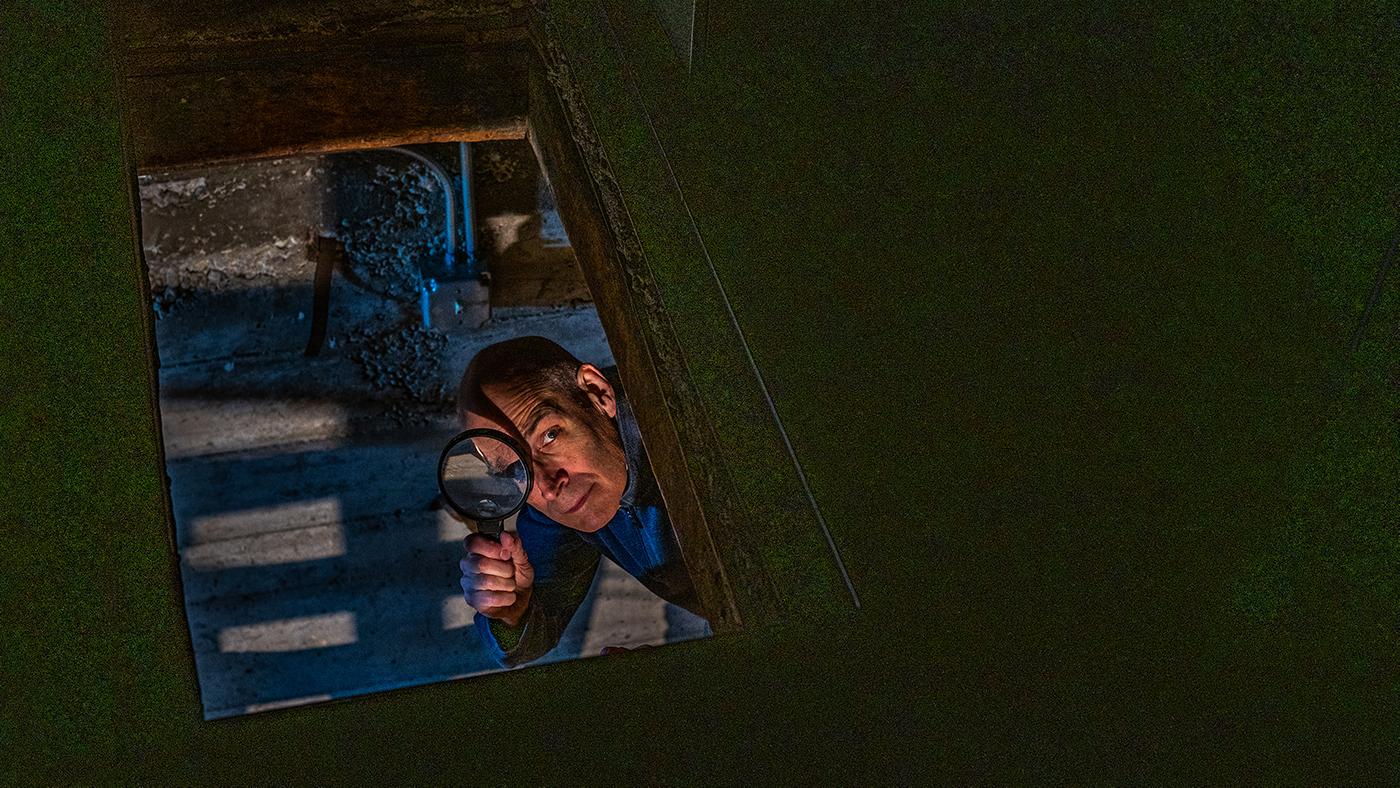

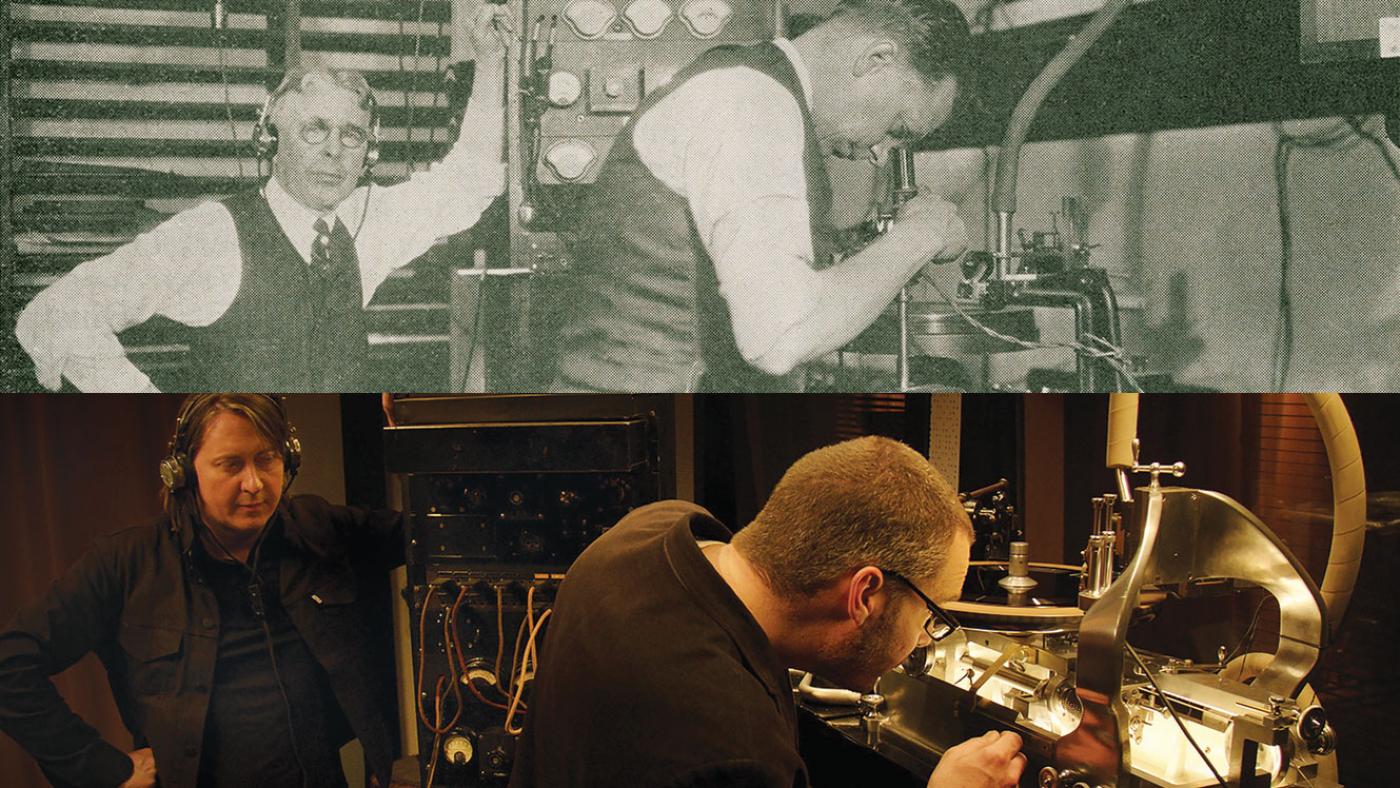

From diving into these recordings, MacMahon also became fascinated with how they were made. He discovered that there was barely any information about the Western Electric machine, and that none had survived in full. But he eventually found a sound engineer named Nick Bergh who had rebuilt one out of original parts scavenged from around the world, and decided to record some musicians to understand the process. That process can be seen in The American Epic Sessions, the final part of the saga.

Jack White recording on an old Western Electric machine for 'The American Epic Sessions.' Photo: ©2017 Lo-‐Max Records Ltd.“If American Epic was likened to the story of the Apollo missions, the first three films might be talking to the engineers at NASA and the astronauts, but your ultimate thing would be, ‘Let’s rebuild the Apollo, fly it to the moon, and film it, and see what we learn about how they did it,’” MacMahon joked.

Jack White recording on an old Western Electric machine for 'The American Epic Sessions.' Photo: ©2017 Lo-‐Max Records Ltd.“If American Epic was likened to the story of the Apollo missions, the first three films might be talking to the engineers at NASA and the astronauts, but your ultimate thing would be, ‘Let’s rebuild the Apollo, fly it to the moon, and film it, and see what we learn about how they did it,’” MacMahon joked.

There were difficulties, such as the need to record everything in one take and the fragility of the machine – at one point, an essential part breaks and Jack White draws on his training as an upholsterer to fix it. But the sessions gave a closer look at an immensely influential machine.

“This recording technology really fundamentally shaped the records that we listen to today,” says MacMahon. Because of the time limit of the Western Electric machine, the standard length for commercial songs became three minutes, a tradition we still follow today. “It was entirely based on that machine and how they calibrated it.”

Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard in 'The American Epic Sessions.' Photo: ©2017 Lo-Max Records Ltd.The new machine also made a wider range of instruments audible on recordings, allowing for more types of music to be captured on disc. Whereas older technology worked by catching sound in a horn and using the resultant vibrations to cut grooves into a disc with a needle, the Western Electric system used a microphone. “Before, you had to scream into a horn, which made many things inaudible,” says MacMahon. “So many of the musics you hear in the film, you couldn’t record on the earlier setup.”

Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard in 'The American Epic Sessions.' Photo: ©2017 Lo-Max Records Ltd.The new machine also made a wider range of instruments audible on recordings, allowing for more types of music to be captured on disc. Whereas older technology worked by catching sound in a horn and using the resultant vibrations to cut grooves into a disc with a needle, the Western Electric system used a microphone. “Before, you had to scream into a horn, which made many things inaudible,” says MacMahon. “So many of the musics you hear in the film, you couldn’t record on the earlier setup.”

The microphone had its own quirks, however, that also affected music. “This microphone favors the small group set-up, particularly vocal-based,” MacMahon explains. “Guitars and voices sound really good on this machine.” This led to a shift in commercial music from big bands and orchestras to smaller, four- or five-piece groups fronted by a singer: the predominant form of music for the next seven or eight decades, at least.

“It’s impossible to underestimate its importance,” asserts MacMahon. “All recording technology today, everything from your iPhone to your radio, basically comes from that technology.”