Chinese Masterpieces at the Art Institute of Chicago

Daniel Hautzinger

July 11, 2017

When Tao Wang came to the Art Institute of Chicago two years ago to head the department of Asian Art, he made a propitious discovery. While surveying the Art Institute’s Chinese collection, of which he is curator, he stumbled upon some works by Huang Binhong. According to Wang, Huang’s paintings had been largely undervalued during his long life (he lived from 1864 to 1955), but about a decade ago museums and collectors began to reappraise his output. Now he is considered one of the greatest twentieth century artists, and his layered-ink, almost impressionistic works are some of the most sought-after Chinese paintings: one recently sold for an impressive $50.6 million at auction.

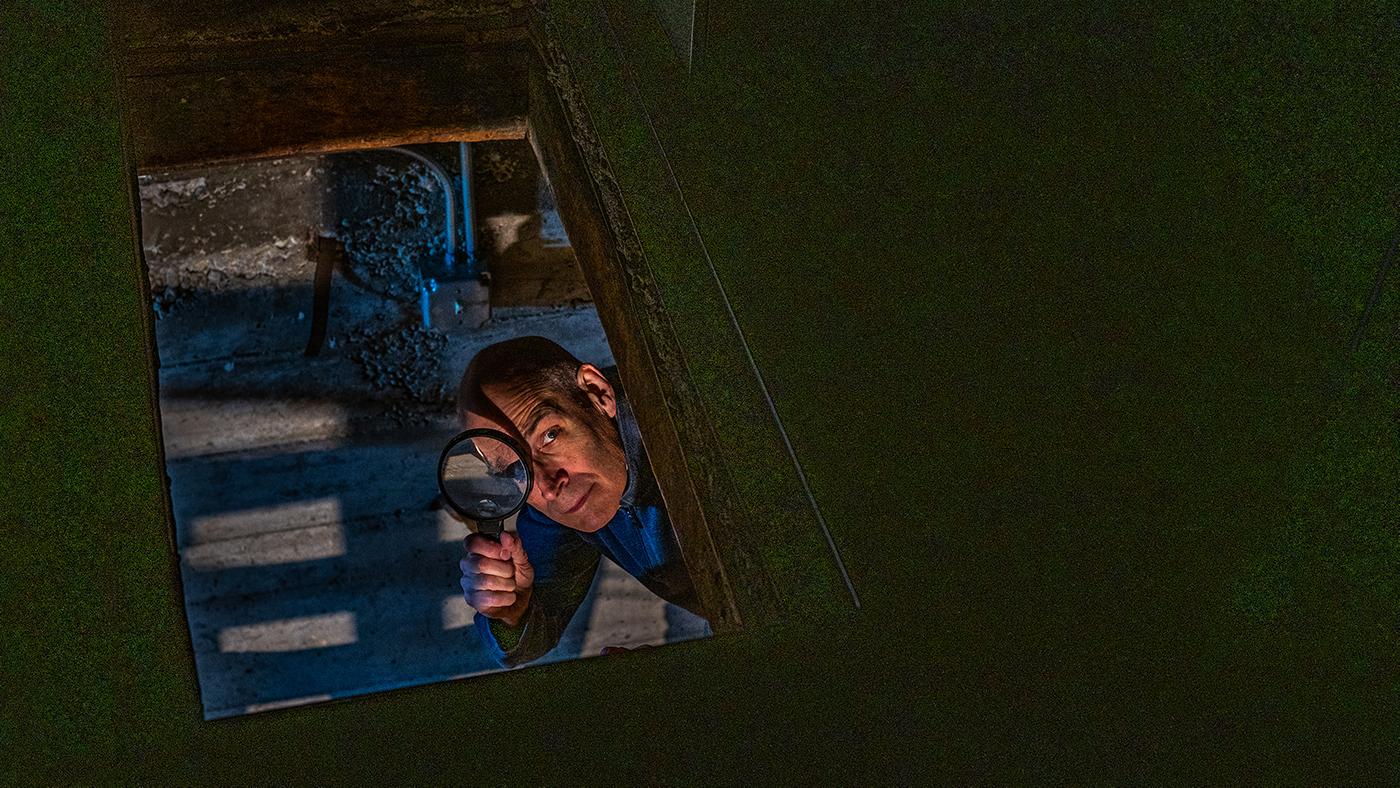

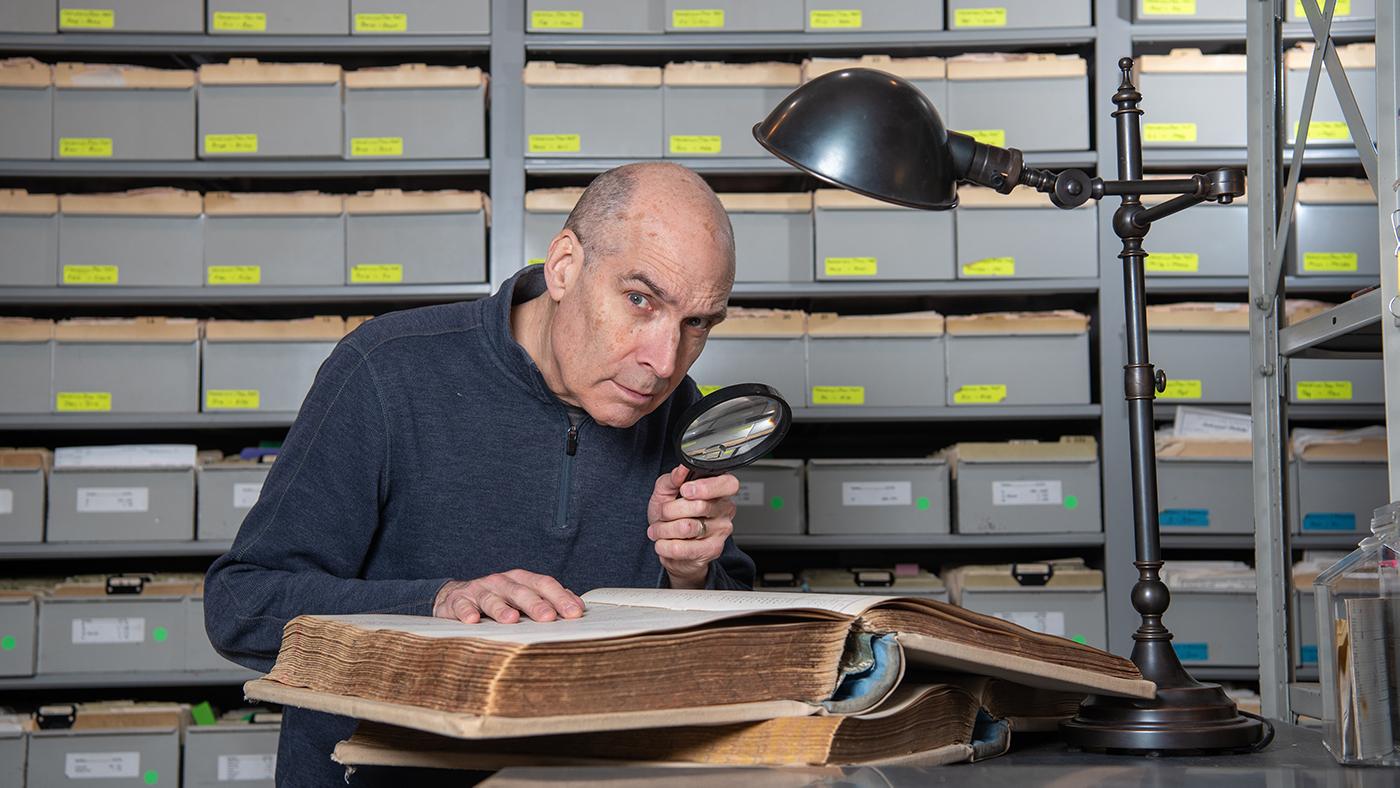

Tao Wang. Photo: Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.But the paintings Wang found at the Art Institute were mislabeled as the work of another artist. They had been donated in the 1970s, back when Huang was relatively unknown. Now they were both valuable and in vogue. If not for Wang’s keen eye, they may have languished in the vaults.

Tao Wang. Photo: Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.But the paintings Wang found at the Art Institute were mislabeled as the work of another artist. They had been donated in the 1970s, back when Huang was relatively unknown. Now they were both valuable and in vogue. If not for Wang’s keen eye, they may have languished in the vaults.

For much of Chinese history, the most esteemed art forms were calligraphy and painting, particularly landscape painting. (Huang Binhong painted landscapes.) But Western collections such as that at the Art Institute tend to favor sculpture and objects, which, at the time when Europeans began collecting Asian artworks, fit in better with Western notions of “art” than inked or painted scrolls.

This is not to say that the Chinese did not value items such as the jade relics, bronze vessels, and ceramics that make up the majority of the collection at the Art Institute. The oldest Chinese items in that collection – and in Chinese art history – are ceramics from the Neolithic period, roughly 5000 to 2000 B.C. Ancient jade pieces from tombs also survive; because jade cannot be carved but instead must be shaped by grinding and polishing, it has long carried powerful symbolic and spiritual value.

Bird-Shaped Wine Container, Late Shang dynasty. Photo: Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.Bronze also emerged sometime in the second millennium BC, during the Shang dynasty, the first traditional Chinese dynasty to leave archaeological evidence. Like jade, bronze holds spiritual resonance; hence, most surviving early bronzes are funerary objects. One exceptionally complex bronze on display at the Art Institute is a wine container in the shape of a bird whose head is being swallowed by a tiger. Wang claims that bird designs are rare in the Shang period, with perhaps only a dozen extant examples.

Bird-Shaped Wine Container, Late Shang dynasty. Photo: Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.Bronze also emerged sometime in the second millennium BC, during the Shang dynasty, the first traditional Chinese dynasty to leave archaeological evidence. Like jade, bronze holds spiritual resonance; hence, most surviving early bronzes are funerary objects. One exceptionally complex bronze on display at the Art Institute is a wine container in the shape of a bird whose head is being swallowed by a tiger. Wang claims that bird designs are rare in the Shang period, with perhaps only a dozen extant examples.

He would know. He is an expert in early ritual bronzes, as well as jades and inscriptions. The first large exhibition that he will curate at the Art Institute focuses on bronze in everyday life, showing how it has been collected and used from the Shang until now. Opening in winter of next year, it will encompass more than 150 pieces, including artifacts on loan from the Shanghai Museum and Beijing’s Palace Museum that have never before been displayed outside China.

Unlike bronzes, one type of art object did find its way outside of China, eventually in mass quantities. Beginning with the Japanese during the Song dynasty (960-1279), foreigners started to covet Chinese ceramics. The Song – the most typically “Chinese” dynasty, according to Wang – developed ceramics into a stunning art form, and their work is still considered the peak of Chinese ceramics. They even used a form of mass production, in which a design was inscribed with a mold instead of by hand.

Jar with the Four Accomplishments: Painting, Calligraphy, Music, Strategy; Ming Dynasty, 15th century. Photo: Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.When the Mongols swept away the Song and became the Yuan dynasty, they opened up trade with Central Asia and the Middle East; some ceramics at the Art Institute have Arabic inscriptions. It was during this period that China’s iconic blue and white porcelain emerged, later adored by Europeans. The ensuing Ming dynasty (1368-1644) attempted to imitate the blue and white, producing, before mastering the style, some rare porcelain whose blue later faded to a reddish color.

Jar with the Four Accomplishments: Painting, Calligraphy, Music, Strategy; Ming Dynasty, 15th century. Photo: Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.When the Mongols swept away the Song and became the Yuan dynasty, they opened up trade with Central Asia and the Middle East; some ceramics at the Art Institute have Arabic inscriptions. It was during this period that China’s iconic blue and white porcelain emerged, later adored by Europeans. The ensuing Ming dynasty (1368-1644) attempted to imitate the blue and white, producing, before mastering the style, some rare porcelain whose blue later faded to a reddish color.

Under the last dynasty, the Qing (1644-1911), imperial factories produced ever larger quantities of incredibly sophisticated products, Wang says. Just look at the luscious hand-painted altar set acquired by the Art Institute last year, one of Wang’s favorite pieces in the entire collection. Ornate, delicate, and beautiful, it exudes refinement; the Qing possessed extraordinary wealth and power, and even employed European artists. Like the paintings of Huang Binhong, the altar set became an important part of the Art Institute’s collection under Wang. Look forward to whatever exquisite pieces he adds next.