A "Colossal Booboo": The Incredible Story of the Chicago Picasso

Daniel Hautzinger

August 7, 2017

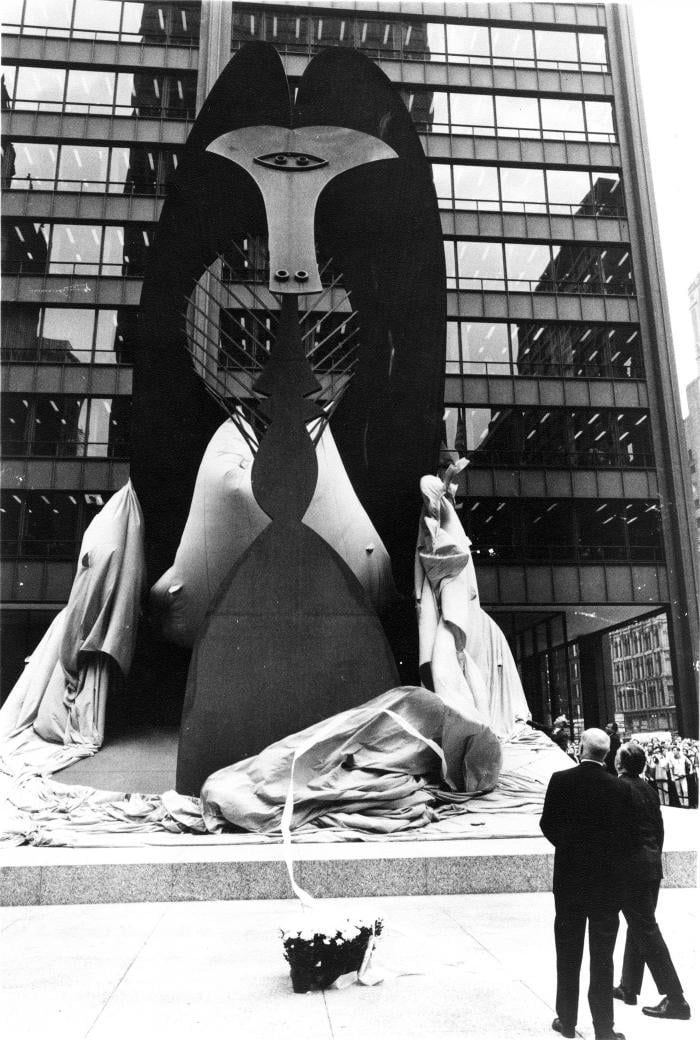

Fifty years ago, a gruff, conservative Irish Catholic family man unveiled a colossal work of sensuous, abstract art designed by a womanizing, dedicatedly Communist artist. Despite antithetical politics, opposite temperaments, and never meeting in person, Richard J. Daley and Pablo Picasso together gave Chicago one of its most iconic emblems and ushered in a new era of public art across the United States with the erection of a 50-foot tall, 162-ton untitled sculpture in Daley Plaza now known simply as the Chicago Picasso.

In honor of the Picasso’s 50th anniversary and Chicago’s Year of Public Art, the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events is restaging the original unveiling ceremony in Daley Plaza, on Tuesday, August 8, at noon.

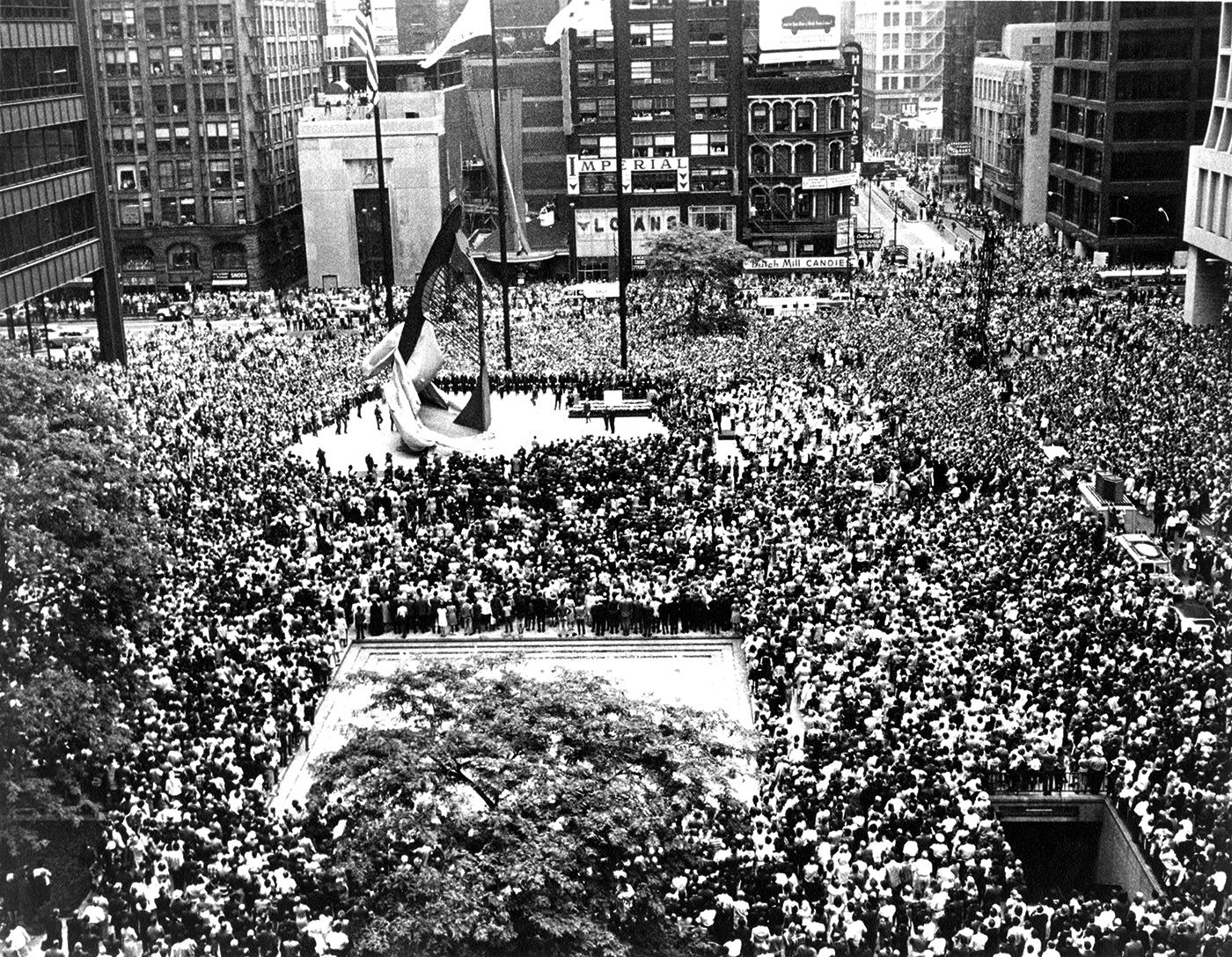

When the sculpture was first revealed to a jam-packed crowd on August 15, 1967, it was met with befuddlement and derision. Protest signs called it “An insult to Chicago’s greatness” and a “colossal booboo,” while an alderman floated a plan to replace it with a statue of Ernie Banks, the legendary Cubs player. People asked what it was: a depiction of Picasso’s Afghan hound? The canine-headed Egyptian god Anubis? A cow sticking its tongue out? “If it’s a bird or an animal, they ought to put it in the zoo,” said Daley’s cantankerous commissioner of special events. “If it’s art, they ought to put it in the Art Institute.” But Daley himself thought it looked like “the wings of justice.” For years after the unveiling, the mayor placed a birthday cake at the base of the sculpture every August 15.

Photo: Courtesy DCASESo how did this no-nonsense politician end up a champion of this piece of modern public art?

Photo: Courtesy DCASESo how did this no-nonsense politician end up a champion of this piece of modern public art?

It began with the construction of the Chicago Civic Center. Designed by architect Jacques Brownson of C. F. Murphy Associates in conjunction with two other firms, the modernist steel building was to be graced by a spacious plaza adorned with a monumental sculpture. Picasso was chosen to be the sculptor by the group of architects. Up to this point, most civic art in America was figurative and traditional: busts of political leaders, statues of military heroes. Picasso himself had never created a large public sculpture, although he had dreamed of doing so.

Fearful of Daley’s response to this bold request, the architects sent their most charming and worldly member, William Hartmann, as an envoy to the mayor. Amazingly, Daley quickly acquiesced; it probably helped that Hartmann appealed to his sense of pride, pitching Picasso as the greatest living artist. Chicago deserved the best.

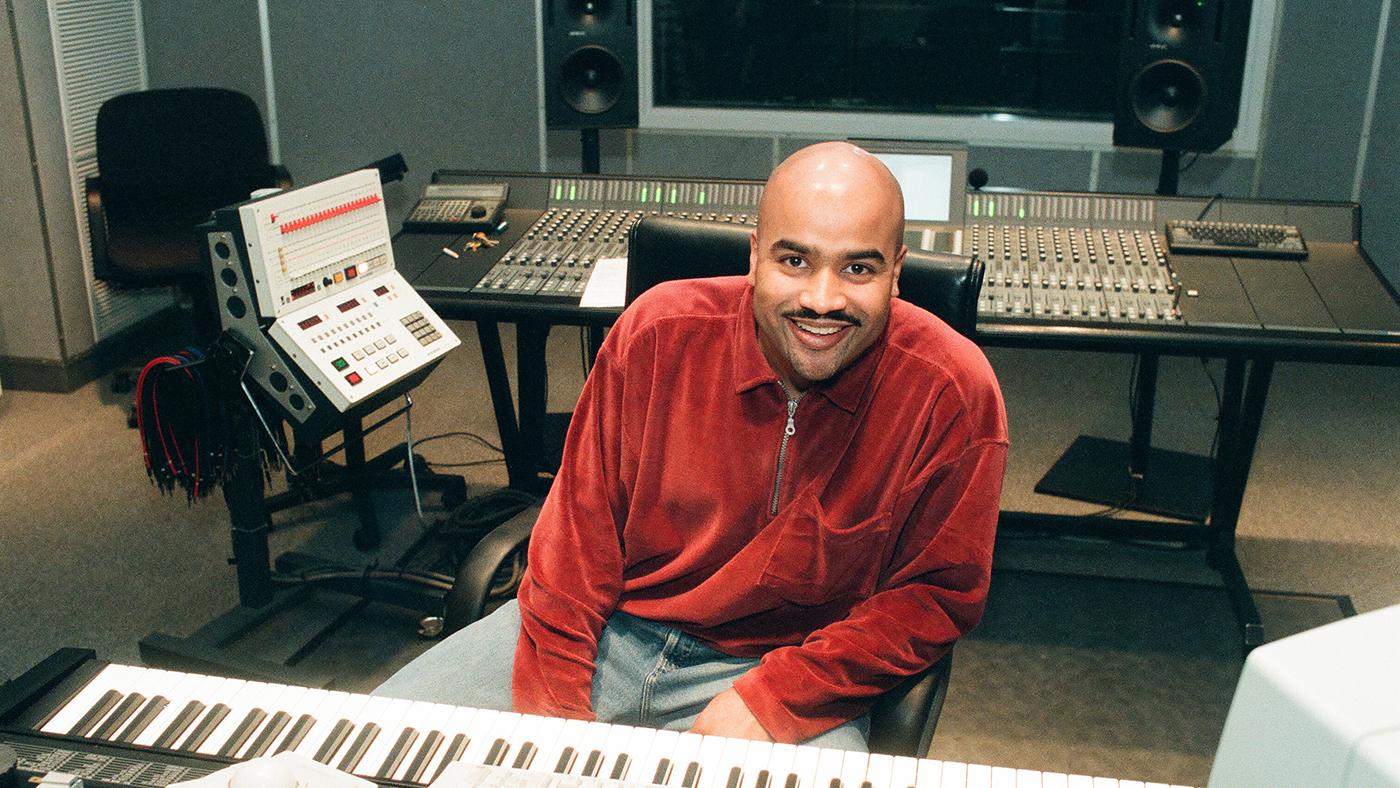

William Hartmann and Richard J. Daley unveiling the Picasso. Photo: Courtesy DCASEHopefully, the best wanted Chicago. Beginning in 1963, Hartmann took several trips to visit Picasso at his home on the French Riviera. Each time he offered gifts – a scrapbook of photos and quotations about the city, a poem, a White Sox jersey, a Native American headdress – to convince the 81-year-old master to take on the project. Finally, after two years, Picasso gave Hartmann a maquette, or prototype model, of the statue. (The maquette is now held by the Art Institute.) When the architect returned with a $100,000 check from Daley as payment, Picasso refused it. “This is my gift to the people of Chicago,” he said.

William Hartmann and Richard J. Daley unveiling the Picasso. Photo: Courtesy DCASEHopefully, the best wanted Chicago. Beginning in 1963, Hartmann took several trips to visit Picasso at his home on the French Riviera. Each time he offered gifts – a scrapbook of photos and quotations about the city, a poem, a White Sox jersey, a Native American headdress – to convince the 81-year-old master to take on the project. Finally, after two years, Picasso gave Hartmann a maquette, or prototype model, of the statue. (The maquette is now held by the Art Institute.) When the architect returned with a $100,000 check from Daley as payment, Picasso refused it. “This is my gift to the people of Chicago,” he said.

The sculpture was crafted in pieces by U.S. Steel in Gary, Indiana. Made of the same COR-TEN steel as the Civic Center that it would front, it called for panels so large that engineers had to improvise new technology to fabricate them. The Picasso was assembled behind a cloth covering in the Civic Center plaza to shield it from the eyes of the public until the unveiling. At the dedication ceremony, Gwendolyn Brooks read a poem she had written for the occasion, while Seiji Ozawa conducted musicians from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, paid for out of Hartmann’s pocket.

After the dedication, the public’s curiosity about the subject of the sculpture remained unsatisfied; Picasso never revealed his inspiration. The artist died six years after the unveiling, without ever setting foot in America. Daley followed three years after that, in 1976. Seven days after the mayor’s death, the Civic Center and its adjoining plaza were renamed in his honor.

The artist and the mayor had inaugurated a new style of public art: Chicago was the first American city to commission an abstract sculpture for its downtown, and other cities soon followed suit. Chicago itself now has an impressive array of modern works, from Joan Miró’s fork-headed Chicago, which stands across the street from Daley Plaza, to Anish Kapoor’s glittering Cloud Gate, otherwise known as The Bean. And still, 50 years later, the Picasso enigmatically stands, grandfather to them all.