The Solar Eclipse: Unlike Anything Else in the Sky

Daniel Hautzinger

August 14, 2017

On August 21, the day of the eclipse, at 9:00 pm, watch NOVA: Eclipse Over America, which will feature footage from the eclipse.

The last time Michelle Nichols experienced a total solar eclipse, she began to sob. Nichols, the Director of Public Observing at the Adler Planetarium, was on an Adler-organized cruise in the Black Sea to observe the eclipse of August 11, 1999. As the moon covered the sun, the temperature dropped some ten degrees, the world went as dark as a full moon night, and it looked as if an enormous hole had opened up in the sky.

“I still don’t completely understand why I had the reaction that I did,” she says. “But you instantly feel a connection to all those people 1,000 years ago who didn’t know this was coming. All of a sudden it happens, and you can utterly understand why they were terrified.”

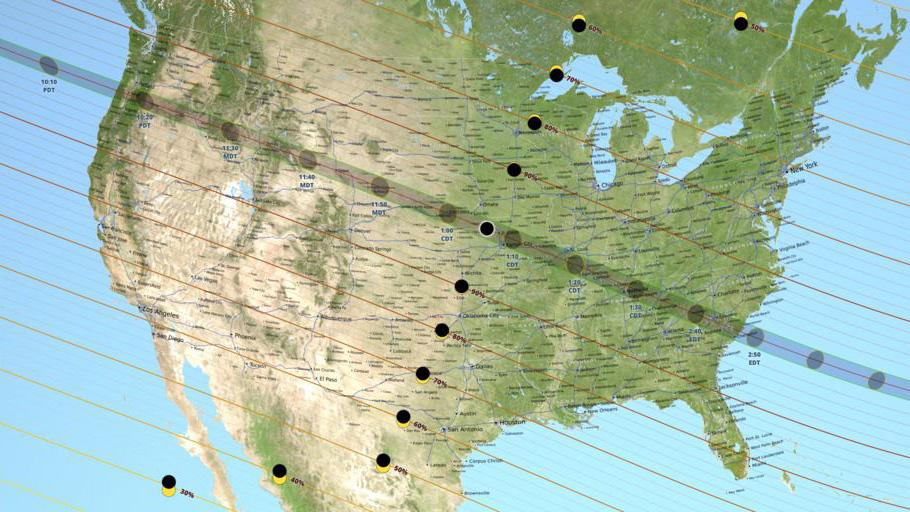

On August 21, Nichols, and others across the country, will again undergo that unearthly and fantastic experience, when a solar eclipse passes over a swath of the United States. The path of totality stretches from Oregon to South Carolina, hitting, among other cities, Lincoln, Nebraska; Kansas City, Missouri; Nashville, Tennessee; Columbia, South Carolina; and Carbondale in southern Illinois – where Nichols and a team from the Adler will be set up to aid in Southern Illinois University’s eclipse events. The last time a total solar eclipse could be seen in any of the lower 48 states was in 1979.

While Chicago itself is not in the path of totality, the moon will begin to cover the sun here at 11:54 am and block out 87% of it by 1:19 pm, moving completely away at 2:42 pm. The last time Chicago saw such a complete eclipse was 1925. Another eclipse in 2024 will bring 94% coverage of the sun to Chicago, but the city won’t experience a total eclipse until 2099.

The eclipse's path of totality over the United States. Image: NASATo celebrate the eclipse, and to help you safely enjoy it, the Adler is offering free general admission and hosting an outdoor block party on their grounds from 9:30 am to 6:00 pm, featuring live entertainment, engaging activities, coverage of the eclipse, food trucks, and more. Adler staff will also be stationed downtown in Daley Plaza to distribute safe solar viewing glasses and answer questions. The Planetarium is also currently featuring an exhibit called Chasing Eclipses, that helps prepare you for the eclipse and offers some background about this timeless event.

The eclipse's path of totality over the United States. Image: NASATo celebrate the eclipse, and to help you safely enjoy it, the Adler is offering free general admission and hosting an outdoor block party on their grounds from 9:30 am to 6:00 pm, featuring live entertainment, engaging activities, coverage of the eclipse, food trucks, and more. Adler staff will also be stationed downtown in Daley Plaza to distribute safe solar viewing glasses and answer questions. The Planetarium is also currently featuring an exhibit called Chasing Eclipses, that helps prepare you for the eclipse and offers some background about this timeless event.

Why do you need to wear special glasses to view the eclipse? “Even if you have 99% of the sun covered, that little tiny bit of exposed sun is still 1,000 times brighter than the full moon,” explains Nichols. Staring directly at that light could cause severe eye damage, so it’s important to wear certified safe solar viewing glasses, such as those the Adler will be handing out at their events. Regular sunglasses won’t cut it.

Even if you don’t have solar viewing glasses, there’s a safe way to observe the eclipse without any equipment. Simply look under trees, and you’ll see focused images of the eclipse on the ground. Holes in the leaf cover will act like pinhole projectors, working as a lens to project the sun on the ground. This is an everyday phenomenon, but the amount of sunlight on a normal day diffuses the projected images so that they’re indefinite and difficult to see.

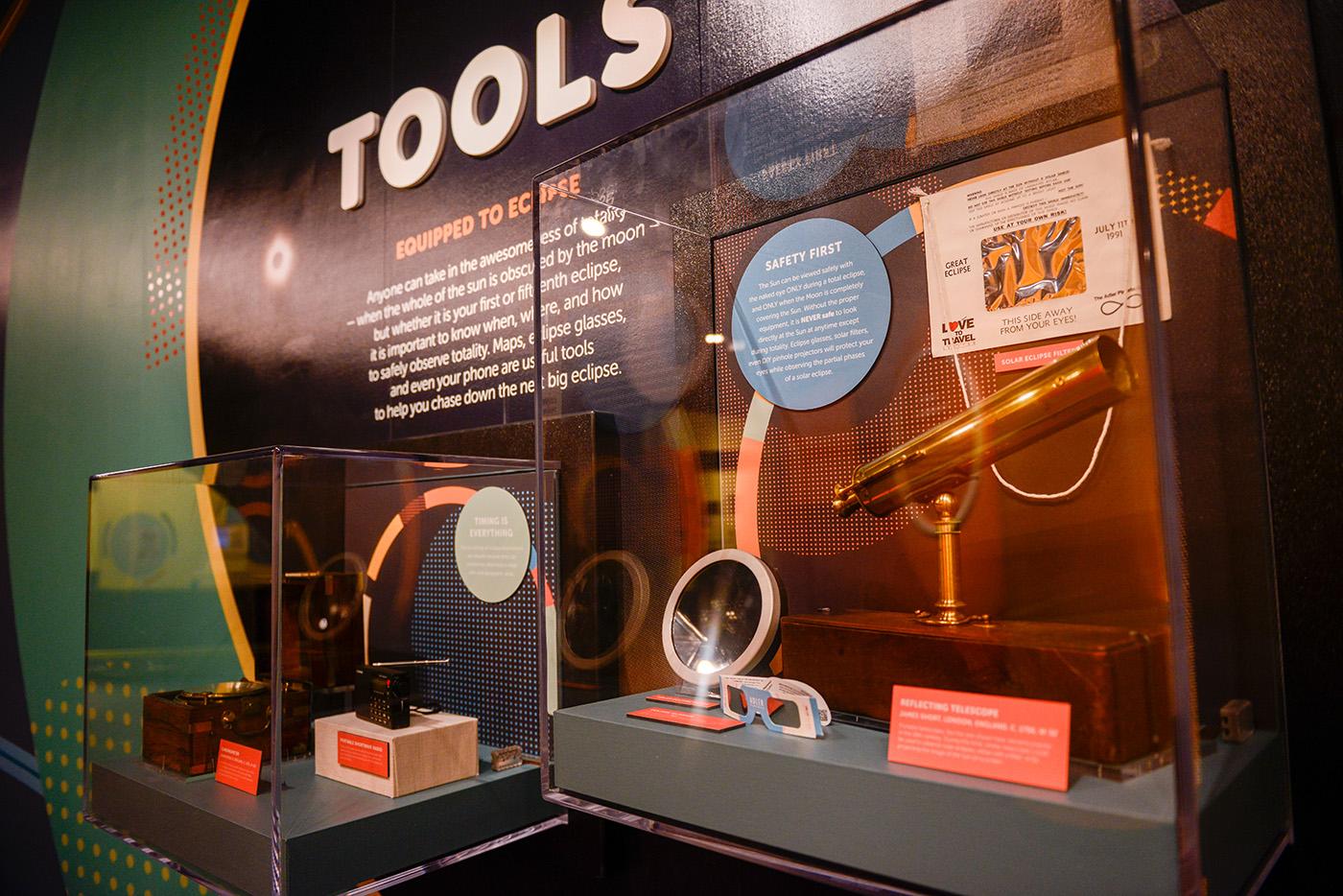

Eclipse-watching tools, old and new, in the Adler Planetarium's Chasing Eclipses exhibit. Photo: Adler PlanetariumEclipses are not only incredible to observe, but also provide an opportunity for valuable research. Nichols explains: “The lit-up part of the sun that we can see every day is called the photosphere. There’s a layer directly above that called the chromosphere that glows red due to excited hydrogen atoms. And above the chromosphere, there’s a wispy outer atmosphere called the corona. The only time you can really see the corona from the surface of the earth is during a total solar eclipse.

Eclipse-watching tools, old and new, in the Adler Planetarium's Chasing Eclipses exhibit. Photo: Adler PlanetariumEclipses are not only incredible to observe, but also provide an opportunity for valuable research. Nichols explains: “The lit-up part of the sun that we can see every day is called the photosphere. There’s a layer directly above that called the chromosphere that glows red due to excited hydrogen atoms. And above the chromosphere, there’s a wispy outer atmosphere called the corona. The only time you can really see the corona from the surface of the earth is during a total solar eclipse.

“You can’t use the same instrument to study both the corona and the sun by itself, because you have to block out a lot of light to image the sun, so you’re not going to get the corona; it’s too dim. It’s only about as bright as a full moon. To study the corona, you have to block out the sun and even a little bit of light around the sun, so you miss part of the corona. Scientists go to solar eclipses to study the gap left between research about the sun and research about the corona. They try to understand a crucial part of the corona that we don’t know that much about.”

Solar eclipses have already enabled groundbreaking findings. Helium was first discovered on the sun, when an astronomer identified a pattern of light specific to the element during a total solar eclipse. It wasn’t until a couple decades later that it was discovered on earth. Hence its name: it derives from Helios, the ancient Greek god of the sun.

Beyond the practical research they enable, however, eclipses are simply awesome. As Nichols says, “Pictures can’t do it justice. It’s unlike anything you’ve ever seen in the sky.”