The People Who Bring Disney Films to Life

Daniel Hautzinger

September 8, 2017

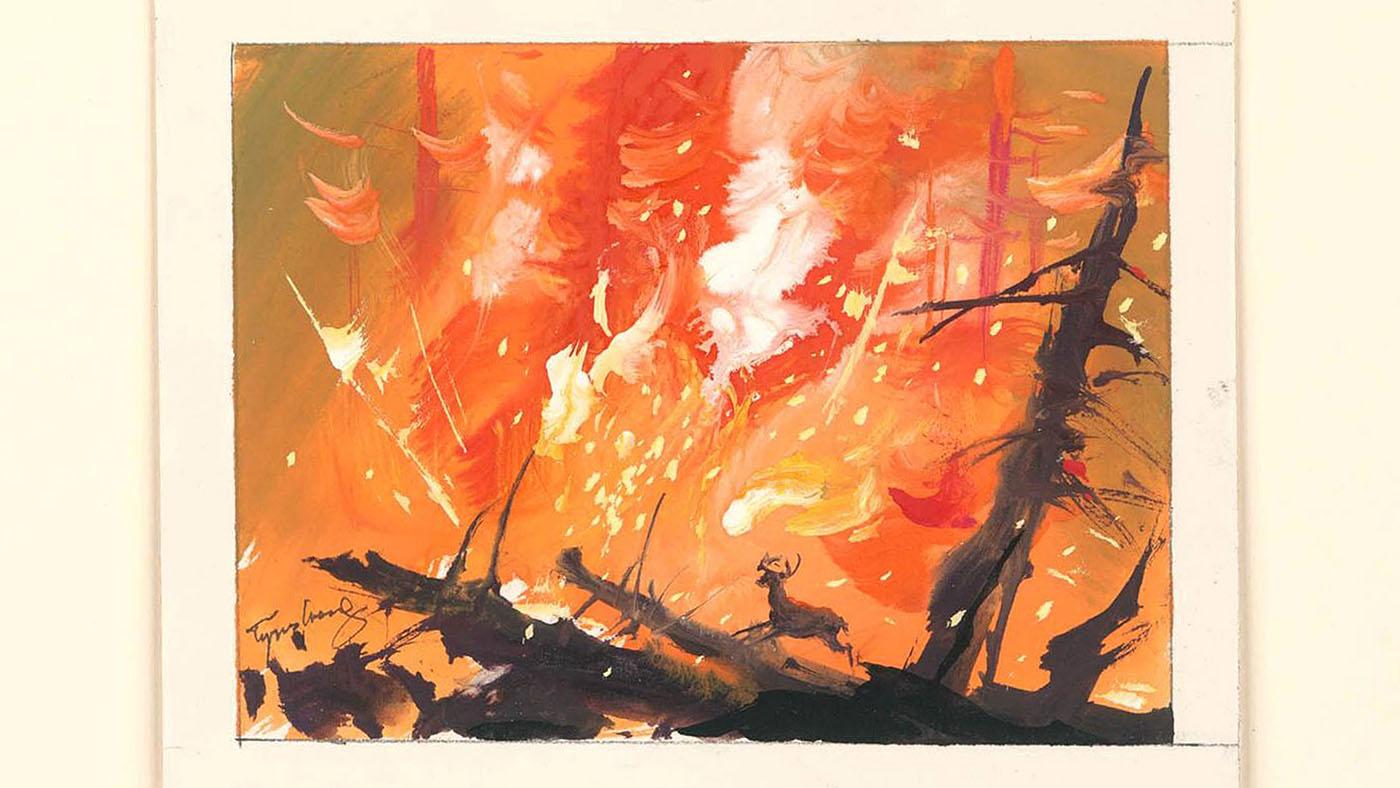

A new American Masters documentary overviews the life and work of the Chinese-American artist Tyrus Wong, a painter, calligrapher, illustrator, and kite-maker who lived to 106 and whose conceptual art defined the look of Bambi, The Sands of Iwo Jima, and Rebel Without a Cause, and other films. Wong’s legacy, especially his contributions to Disney, were obscured for a long time because of racist attitudes, but in the past two decades or so his work began to be recognized.

Other Disney animators, stylists, designers, and art directors may be better known than Wong (especially some of the men, given that animation is a male-dominated world and was even more so while Walt Disney was alive), but most of them aren’t household names. Meet some of the people responsible for envisioning, drawing, and bringing to life your favorite childhood characters and landscapes in Disney movies through the decades. (Three more Disney animators – Ruthie Tompson, Milton Quon, and Don Lusk – are included on our list of living centenarian artists.)

Tyrus Wong at work

Tyrus Wong at work

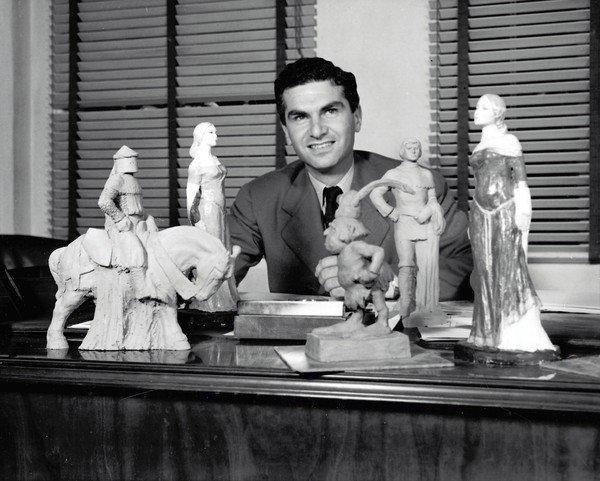

Wolfgang “Woolie” Reitherman (1909-1985)

“Woolie” Reitherman was part of a cadre of animators that Walt Disney teasingly referred to as the “Nine Old Men.” After an initial interest in aircraft engineering – one that came to fruition during World War II, when he earned a Distinguished Flying Cross flying missions over India, China, Africa, and the South Pacific – Reitherman became interested in watercolors and then animation. He joined Disney in 1933 and became known for his action sequences in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Fantasia, Sleeping Beauty, and Pinocchio. He stepped into Walt Disney’s role as producer and director after Disney’s death in 1966, directing The Jungle Book and Robin Hood, among others. He retired in 1981 after almost fifty years at Disney.

Ward Kimball (1914-2002)

Another one of Disney’s “Nine Old Men,” Kimball joined Disney in 1934, staying until 1973. He helped redesign Mickey Mouse in 1938, created Jiminy Cricket for Pinocchio, and also worked on such films as Dumbo, Cinderella, Peter Pan, and many others. He loved model trains – an enthusiasm he shared with Disney and another “Old Man,” Ollie Johnston – and even had a coal-burning locomotive in his backyard with 900 feet of track. He was also a prankster: his “Disney Legend” handprints have extra fingers.

Ward Kimball, known for pranks, added an extra finger to his Disney Legend handprints, on the top right.

Ward Kimball, known for pranks, added an extra finger to his Disney Legend handprints, on the top right.

Marc (1913-2000) and Alice (b. 1929) Davis

Marc Davis and Alice Estes met while he was an instructor and she was a student at the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles. Marc had started at Disney in 1935, and created such characters as Tinker Bell (Peter Pan), Princess Aurora and Maleficent (Sleeping Beauty), and Cruella de Vil (One Hundred and One Dalmatians). Alice designed costumes for live-action footage used for reference by Disney animators. The couple eventually collaborated in designing the Disneyland attraction Pirates of the Caribbean, while Marc also worked on it’s a small world and the Haunted Mansion.

Mel Shaw (1914-2012)

Born Melvin Schwartzman, Shaw worked with Orson Welles on an unrealized adaptation of The Little Prince before meeting Walt Disney while playing polo. He joined Disney in 1937 and contributed to Fantasia, Dumbo, and Bambi, among other films, before leaving to be an army photographer and cartoonist. He later formed a production company that designed the Howdy Doody puppet, then returned to Disney as a mentor in 1974, working on Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King, among others. He also painted California history scenes and horses, which he loved to ride.

Mel Shaw. Photo: Courtesy Disney

Mel Shaw. Photo: Courtesy Disney

Mary Blair (1911-1978)

Blair managed to succeed in a male-dominated world, as a designer and art director for films like Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, and The Three Caballeros, using her paintings to supervise and lead their artistic direction. Marc Davis compared her use of color to Matisse; like Davis, she worked on Disneyland attractions such as it’s a small world. She also did commercial illustrations, window displays, theater sets, and children’s books. She joined Disney in 1940, after working for MGM.

Glen Keane (b. 1954)

Keane is part of the second generation of animators who ushered in a new golden age at Disney. He joined the company in 1974, working on The Rescuers and more, and conducting some of Disney’s first experiments with digital technology. He left in 1983 but soon returned to animate such iconic figures as Ariel (The Little Mermaid), the Beast (Beauty and the Beast), Aladdin, Pocahontas, and Tarzan. He also developed and eventually produced Tangled, after which he retired from Disney in 2012.

Glen Keane was the major force behind 'Tangled.' Image: Courtesy Disney

Glen Keane was the major force behind 'Tangled.' Image: Courtesy Disney

Andreas Deja (b. 1957)

Like Keane, Deja is a second-generation animator responsible for beloved characters, especially villains: The Lion King’s Scar, Aladdin’s Jafar, The Beauty and the Beast’s Gaston. He has also animated heroes: Hercules, Lilo in Lilo & Stitch, and Mama Odie in The Princess and the Frog. He joined Disney’s animation training program in 1980, having written a letter to the company as a child after being inspired by The Jungle Book. He is currently the subject of an exhibit at the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco.

Brad Bird (b. 1957)

Bird’s career in animated films began when he sent Milt Kahl, another of Disney’s “Nine Old Men,” a remake of an early Disney short, The Tortoise and the Hare, by Kahl’s fellow “Old Man” Ollie Johnston. Bird worked very briefly at Disney in the early ‘80s, then went on to develop The Simpsons and direct, write, and produce The Iron Giant. In 2000, he moved to Pixar, which had a relationship with Disney and eventually became its subsidiary. Bird no longer animates, but was the director and writer of The Incredibles and Ratatouille, and has also directed the live-action films Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol and Tomorrowland. He cites Johnston and his colleague Frank Thomas as great influences, and the pair had cameos in both The Iron Giant and The Incredibles, where they have the sly line: “No school like the old school.”

Brad Bird directed and wrote The Incredibles. Image: Courtesy Disney/Pixar

Brad Bird directed and wrote The Incredibles. Image: Courtesy Disney/Pixar

Ronnie del Carmen (b. 1959)

Like Bird, del Carmen joined Pixar in 2000, having already worked at Dreamworks on The Prince of Egypt. At Pixar, he immediately became a story supervisor for Finding Nemo. He went on to work on art and stories for Ratatouille, WALL-E, Up, Brave, and Monsters University, and was nominated for an Academy Award for Inside Out, which he co-directed and for which he co-wrote the story. Born in the Philippines, del Carmen took part in protests that overthrew the dictator Ferdinand Marcos, but eventually followed his father to the U.S., who had been working here for over a decade.