The Only Bank Prosecuted for the 2008 Financial Crisis

Daniel Hautzinger

September 11, 2017

Frontline – Abacus: Small Enough to Jail is available to stream.

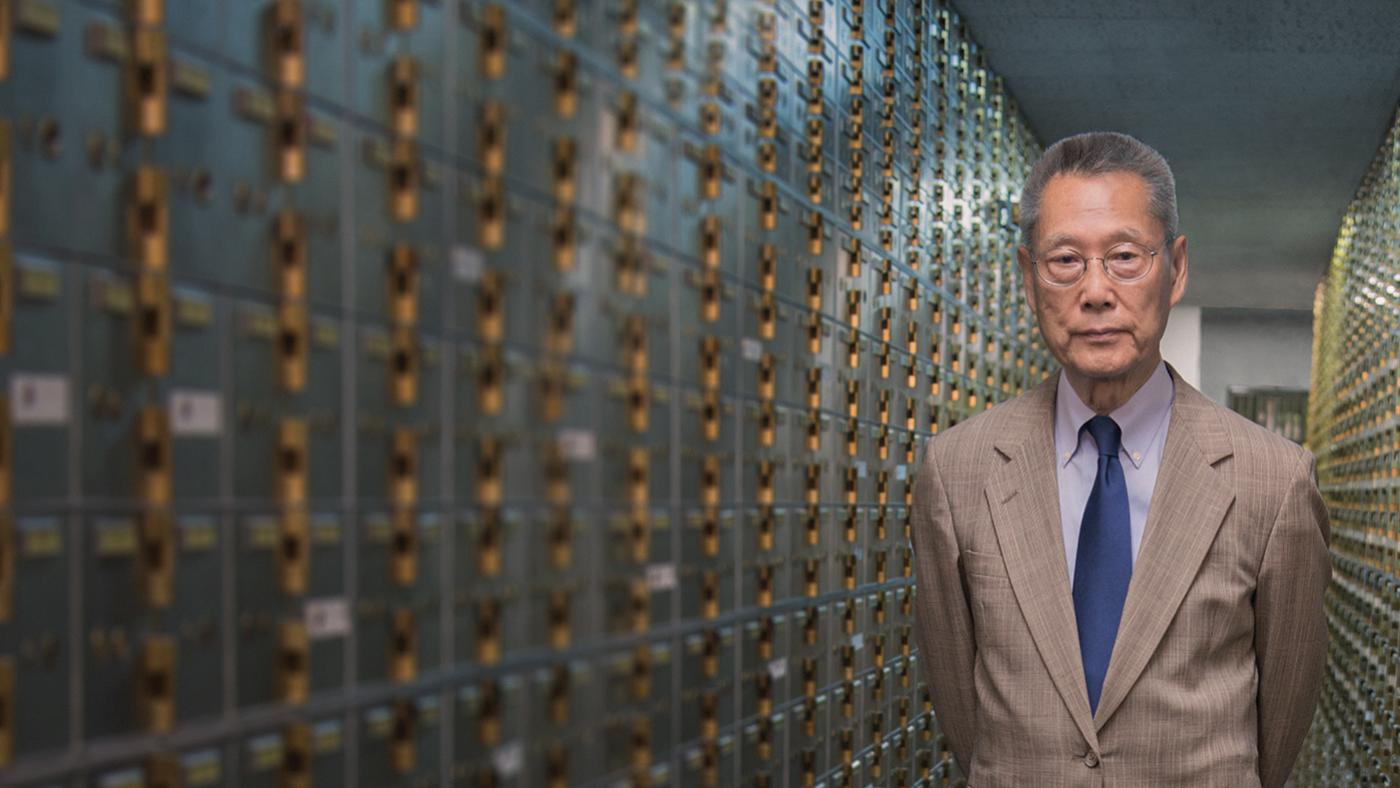

In 2015, Abacus Federal Savings Bank was the 2,651st largest bank in the United States. It was also – and still is – the only U.S. bank prosecuted for the 2008 financial crisis.

Founded in 1984 by Thomas Sung, a native of Sichuan province in China who immigrated to the U.S. with his family in 1951, Abacus serves the unique needs of the residents of New York City’s Chinatown, often first- or second-generation immigrants who speak little or no English and exist primarily in a cash world. Sung had an upstanding reputation in the neighborhood: he had begun his career as an immigration lawyer in the community. Since 2005, his daughter Jill had served as C.E.O. and president of the bank.

In 2009, after the discovery of fraud committed by several employees, Abacus fired them, instigated an internal investigation, reported its findings to the government, and brought in outside investigators. “They did everything you’re supposed to do if you discover you have fraud, yet their reward was to be prosecuted by the District Attorney of Manhattan,” says Steve James, the director of Abacus: Small Enough to Jail, which airs as a Frontline investigation on September 12. Cyrus Vance, the district attorney, indicted the bank on 184 counts in 2012, launching a prosecution that culminated in a trial in 2015. James’s documentary follows the Sungs through the course of that trial.

Steve James, director of 'Abacus: Small Enough to Jail.' Photo: Greg Gorman“I think Vance saw this as an opportunity to be the DA who actually brought a bank to trial in the wake of this crisis – he even invited the Feds to stand behind him when he made the indictment announcement,” James says. “I do think he believed that the bank was guilty of fraud. But I also believe that his ambition clouded his judgment as to whether he should have brought this case or not. And I think that, in the way they went about prosecuting the case, they showed a profound level of cultural insensitivity to the realities of banking in that community or any immigrant community that is trying to climb their way up the ladder. There was a lot of unintended racism – that it’s unintended doesn’t negate the fact that it’s damaging.”

Steve James, director of 'Abacus: Small Enough to Jail.' Photo: Greg Gorman“I think Vance saw this as an opportunity to be the DA who actually brought a bank to trial in the wake of this crisis – he even invited the Feds to stand behind him when he made the indictment announcement,” James says. “I do think he believed that the bank was guilty of fraud. But I also believe that his ambition clouded his judgment as to whether he should have brought this case or not. And I think that, in the way they went about prosecuting the case, they showed a profound level of cultural insensitivity to the realities of banking in that community or any immigrant community that is trying to climb their way up the ladder. There was a lot of unintended racism – that it’s unintended doesn’t negate the fact that it’s damaging.”

The prosecution of Abacus was framed as an instance of justice and accountability after the devastating 2008 financial crisis caused by subprime mortgages and risky lending practices. But, according to James, Abacus took no part in what he calls the “scurrilous activities” of larger banks, activities that led to the crisis. “Abacus refused to participate in any of those things that were going on at the big banks. They saw it for what it was and they declined to do it. They didn’t come out of the crisis damaged at all, until the DA went after them.”

So why weren’t any of the big banks, the true causes of the crisis, prosecuted?

It’s the concept of “too big to fail,” which was promoted by Obama’s Attorney General Eric Holder. Because big banks are so bloated that they are a huge part of the economy, controlling massive sums of money and employing tons of people, there were fears that prosecuting them would severely affect the economy. The prosecution of Enron and its accounting firm Arthur Andersen in the early 2000s provided a case in point. As James explains, “When the Feds went after Enron, they ultimately didn’t get all that they wanted, and they spent an enormous amount of money. They basically put Arthur Andersen, this huge accounting firm, out of business, and something like 20,000 people were thrown out of their jobs.”

After this illustration of collateral damage, the Justice Department began to move towards simply fining big banks and forcing them to acknowledge wrongdoing instead of prosecuting and indicting them. “On some level, I understand,” says James. “There were so many banks involved in the 2008 financial crisis that the impact could have been great if the Justice Department had tried to prosecute all of them. But there are people smarter than me that believe that, without putting them out of business, the banks should at least have been broken up.”

James believes that Vance – who appears in the film – wanted to appease public resentment over the financial crisis but, realizing the difficulties of and restrictions on going after a big bank, saw an opportunity with Abacus. “The fight to take down a huge bank, with all they can bring legally and otherwise, is a whole different animal than taking on a Chinese-American community bank,” he says. “I think they thought that Abacus would plead out and never come to trial.”

But the Sungs fought back. In addition to Thomas, two of his daughters, Vera and Chanterelle, are attorneys, and both had worked for a DA’s office. “One of the reasons they fought this fight was not just to save their bank, but also on behalf of their community,” says James. “There’s inequity in the way that the law treats the Chinese community, and a sense that they are not treated fairly. The fact that Abacus was gone after the way it was reinforced some of those ideas. So the Chinese community is not politically engaged – coming from mainland China, being active politically is not something that one does, and they feel that they are politically disenfranchised here. That’s why you hear Mr. Sung at the end of the film saying, ‘We have to be more engaged. We can’t let this happen again.’ The Sungs saw this as a bigger fight. The DA completely underestimated this family.”