The Clash of Wealth and Labor in Chicago's Gilded Age

Daniel Hautzinger

February 6, 2018

American Experience: The Gilded Age is available to stream.

In the three decades between the end of the Civil War and the start of the twentieth century, the United States underwent unprecedented economic growth, beginning its ascendance as a global economic powerhouse. The exorbitant fortunes amassed by bankers, railroad tycoons, and other titans of industry caused Mark Twain to dub the period “The Gilded Age:” their great wealth was a thin, glamorous layer of gold that masked stark inequality and social ills as the working classes and poor were forced to work more and more for less and less.

Of all American cities, Chicago is perhaps the most vivid example of the Gilded Age in all its glory and squalor. It experienced unbelievable growth through the period: in 1870 its population was just under 300,000; three decades later it was almost 1.7 million, making it one of the five largest cities in the world just 60 years after its founding. As the city was rebuilt after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, it became the birthplace of the skyscraper and a hotbed of innovative architecture, and in 1893 Chicago established itself as an important global city with the celebrated World’s Columbian Exposition.

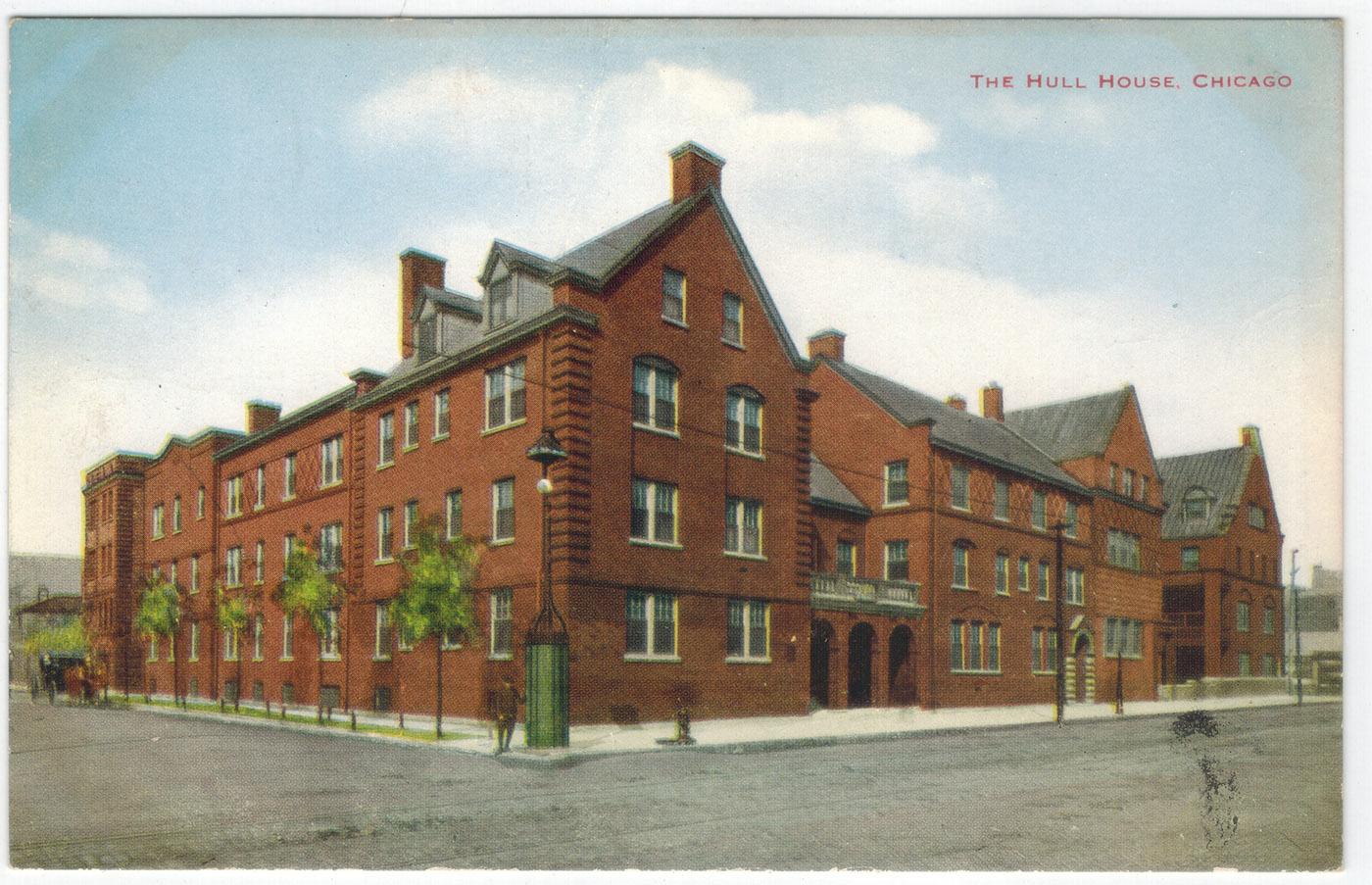

But it also epitomized the social problems of the time. Much of that huge population surge was made up of poor European immigrants who lived in overcrowded slums on the West and South Sides, doing grueling work for low wages in the city’s stockyards, factories, and on the railroads. (Jane Addams’ Hull House was founded during this era, to help immigrants on the West Side.) Unfair conditions led to agitation for change, with some of the most significant events in the labor movement occurring in Chicago.

Jane Addams founded Hull House in 1889 to address the problems of the immigrant poor on Chicago's West Side

Jane Addams founded Hull House in 1889 to address the problems of the immigrant poor on Chicago's West Side

The first major labor incident in Chicago was part of a nationwide railroad strike that began in West Virginia in 1877 after a railroad company continually slashed wages due to an economic depression. Although unions were not yet widespread, thousands of Chicagoans joined the strike. Militia and police were called in to brutally suppress the unrest; some 30 workers were killed and many more wounded. In the wake of the massacre, workers flocked to the labor-supporting Socialist party, making Chicago the country’s strongest socialist bastion.

Only nine years later, the city became the site of another infamous disaster when tens of thousands of workers joined a strike for an eight-hour workday in 1886. As more and more workers walked off the job in the next few days, clashes between police and strikers continually flared up. After two strikers were killed at the McCormick reaper plant (the McCormicks were one of Chicago’s prominent tycoon families), anarchists organized a protest at Haymarket Square on May 4. Police eventually ordered the peaceful gathering to disperse; someone threw a bomb at the police; they retaliated with confused gunfire. At least eight officers and several civilians died in the chaos, and numerous more were injured.

Although the bomb-thrower was never identified, eight prominent anarchists were tried. In a notoriously unjust case, seven were sentenced to death despite a lack of evidence. Four were hanged, one committed suicide, and the remaining three were eventually pardoned. The Haymarket Affair inspired labor movements around the world, including May Day celebrations of international workers.

The Glessner House by Henry Hobson Richardson is one of the few Gilded Age-era mansions left on Prairie Avenue's "Millionaire's Row"

The Glessner House by Henry Hobson Richardson is one of the few Gilded Age-era mansions left on Prairie Avenue's "Millionaire's Row"

Such widespread anger and unrest made Chicago’s elite nervous. Many of them made their home on Prairie Avenue between 16th and 31st streets, a stretch nicknamed “Millionaire’s Row” that offered easy access to downtown unimpeded by a river crossing. The grain elevator owner Daniel Thompson was the first to build a mansion in this conveniently located area in 1869. Chicago’s richest man, Marshall Field, quickly followed suit, and soon other titans of industry flocked there as well: meatpacker Philip Armour, wagon-maker Peter Studebaker, stockyard owner John Sherman, piano magnate William Kimball. They threw opulent galas and lived in mansions designed by the likes of Daniel Burnham and Henry Hobson Richardson, whose 1887 home for the farm machinery manufacturer John Glessner is considered a masterpiece and still stands today as a museum. (Kimball’s house also survives, and is now the headquarters of the U.S. Soccer Federation.)

Anxious that this “sunny street of the sifted few” would eventually be targeted by strikers or anarchists, many of the businessmen who lived on Prairie Avenue pushed for the establishment of a federal military base near Chicago to have troops close, ready to quell unrest. Buying land and then donating it to the federal government, they succeeded in having Fort Sheridan created north of the city two years after the Haymarket Affair.

The troops were called to action several years later, when another epochal strike was called during an economic downturn. In 1894, George Pullman – a resident of Prairie Avenue – laid off workers and cut wages by as much as half for his Pullman Palace Car Company. Despite controlling much of Pullman, the town he had set up for his workers on the South Side, he didn’t reduce rents or utility costs to compensate for the wage cuts. Unsurprisingly, the workers went on strike with the support of the American Railway Union, whose membership then boycotted trains that included Pullman cars.

George Pullman instigated a strike with far-reaching consequences when he slashed wages but didn't cut rents or utilities in his company town of Pullman, on the South Side

George Pullman instigated a strike with far-reaching consequences when he slashed wages but didn't cut rents or utilities in his company town of Pullman, on the South Side

Railroad traffic across the country all but stopped. The federal government stepped in, issuing an injunction against the boycott, dispatching troops (including from Fort Sheridan) to prevent workers from interfering with trains, and arresting the leader of the Railway Union, Eugene Debs, who was subsequently convicted despite a defense by the legendary lawyer Clarence Darrow. While the strike failed in its demands and also lacked widespread sympathy, it ruined George Pullman’s reputation. In 1898, he was forced by the Illinois Supreme Court to divest ownership of the town of Pullman.

The millionaires began moving away from Prairie Avenue as factories, railroads, and a red light district encroached. Their opulent mansions were turned into boardinghouses or bordellos or torn down outright to make room for new industries. The decline of the tony neighborhood dovetailed with the end of the Gilded Age, as populists and progressives began instituting social reform and economic regulation. The gilt was scraped off and the squalor exposed.