Frederick Douglass's Defiant Stand at Chicago's World's Fair

Daniel Hautzinger

February 14, 2018

This story was published in 2018.

Frederick Douglass never knew the date of his own birth, or even how old he was. “I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it,” he wrote. “I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday,” he continued in his 1845 autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. But the famous abolitionist and orator eventually chose to celebrate his birthday on February 14, determining that he was probably born in 1818, 200 years ago.

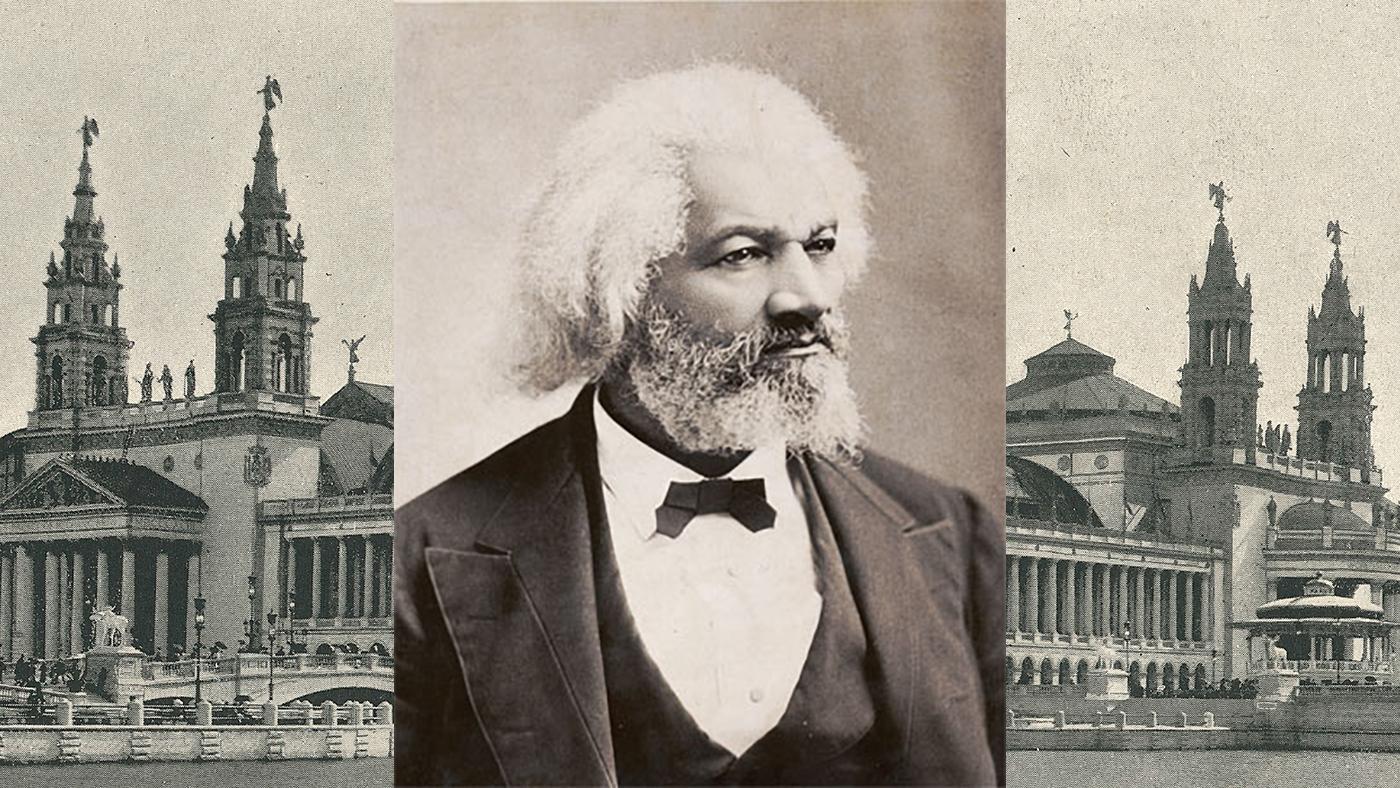

So when Douglass served as the most prominent representative of African Americans at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, from which his race had largely been excluded despite earnest protestation and petition, he was roughly 75 years old.

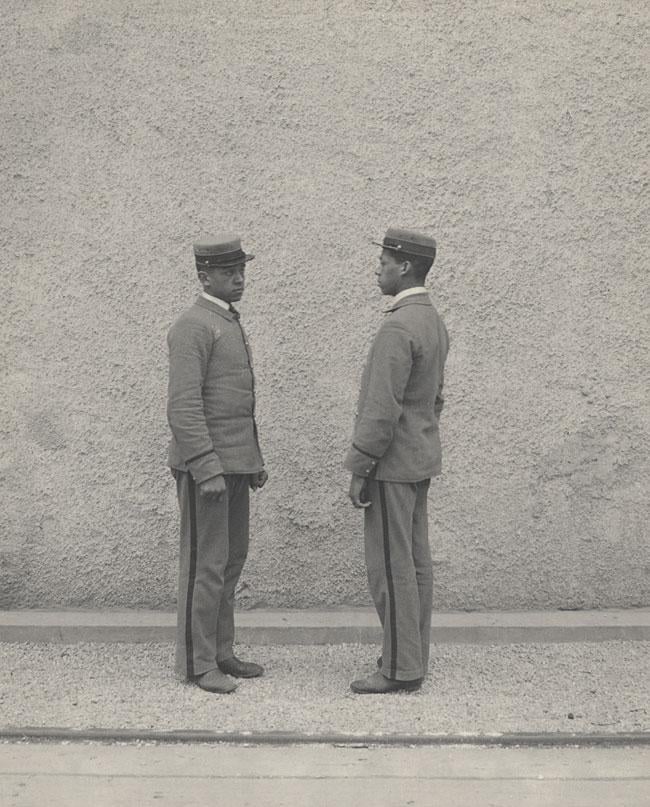

While excluded from leadership or administrative roles at the Fair, African Americans did find work in the service sectorsThe organization of the Exposition was in the hands of a Board of Commissioners appointed by President Benjamin Harrison. With seven and a half million people, African Americans made up more than an eighth of the population of the United States, yet Harrison did not appoint a single black commissioner or alternate (eventually one black alternate was chosen, from Missouri). Only one state, New York, appointed a black representative to the Fair; only three of the hundreds of clerical positions associated with the Fair were filled by African Americans; and all black applicants, no matter how qualified, were rejected to serve in the Exposition’s police force, the Columbian Guard.

While excluded from leadership or administrative roles at the Fair, African Americans did find work in the service sectorsThe organization of the Exposition was in the hands of a Board of Commissioners appointed by President Benjamin Harrison. With seven and a half million people, African Americans made up more than an eighth of the population of the United States, yet Harrison did not appoint a single black commissioner or alternate (eventually one black alternate was chosen, from Missouri). Only one state, New York, appointed a black representative to the Fair; only three of the hundreds of clerical positions associated with the Fair were filled by African Americans; and all black applicants, no matter how qualified, were rejected to serve in the Exposition’s police force, the Columbian Guard.

To publicize this discrimination, Douglass joined forces with the young activist Ida B. Wells, her future husband Ferdinand Lee Barnett, and the journalist Irvine Garland Penn to write and distribute a pamphlet titled The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition at the Fair. “Theoretically open to all Americans, the Exposition practically is, literally and figuratively, a ‘White City,’ in the building of which the Colored American was allowed no helping hand, and in its glorious success he has no share,” wrote Barnett, who was a founder of Chicago’s first black newspaper, The Conservator, and later became Illinois’s first black assistant state’s attorney. “It remained for the Republic of Hayti [sic] to give the only acceptable representation enjoyed by us in the Fair.”

Haiti, which had won its independence from France almost 90 years earlier after a successful slave revolution, was the only black nation with a pavilion in the Fair’s “White City,” named for the gleaming, whitewashed buildings. The proud country appointed Douglass, who had served as a minister of the U.S. government in Haiti, as one of its representatives at the Fair. Whereas Wells had come to Chicago to protest the exclusion of African Americans from the Fair, Douglass was an official part of the Exposition, though he was no less critical for being so.

The Haitian Pavilion was the only building representing a black nation within the Fair's White City

The Haitian Pavilion was the only building representing a black nation within the Fair's White City

Wells and Douglass also differed in their attitude toward the Exposition’s designated Colored American Day, on August 25. Wells and other black elites saw it as a derogatory concession by the Fair’s organizers towards African Americans and refused to participate (other cultural groups such as the Irish or Germans also had specific days allotted them.) Douglass took it as an opportunity, however small, to demonstrate the achievements of black Americans in the 28 years since the end of slavery, and helped organize the celebrations.

The day consisted of musical performances and speeches, including one by Douglass in which he discussed the “Negro problem.” “There is, in fact, no such problem,” he said. “The real problem has been given a false name. It is called Negro for a purpose. It has substituted Negro for Nation, because the one is despised and hated, and the other is loved and honored. The true problem is a national problem. The problem is whether the American people have honesty enough, loyalty enough, honor enough, patriotism enough to live up to their own Constitution.” The event was such a success, despite protests by prominent black citizens, that Wells reportedly apologized to Douglass afterward for her opposition.

Ida B. Wells came to Chicago during the World's Fair to protest its exclusion of blacks and disagreed with Douglass on participating in the FairNotwithstanding the attention given it in the white press, Colored Americans Day was of less importance to African Americans than the Haiti Pavilion and other events, notes Christopher Reed, the author of All the World is Here! The Black Presence at White City. The weeklong Congress on Africa, held earlier in August, brought together leading black intellectuals such as Douglass, Wells, Barnett, and Bishop Henry McNeal Turner, who was famous for asserting that “God is a Negro.” A conference was held on the education of black youth in America. And during the widely covered World’s Congress of Representative Women, which included the suffragists Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and women from around the globe, six African American women spoke about the progress of black women since emancipation. “The exceptional career of our women will yet stamp itself indelibly upon the thought of this country,” promised Fannie Barrier Williams.

Ida B. Wells came to Chicago during the World's Fair to protest its exclusion of blacks and disagreed with Douglass on participating in the FairNotwithstanding the attention given it in the white press, Colored Americans Day was of less importance to African Americans than the Haiti Pavilion and other events, notes Christopher Reed, the author of All the World is Here! The Black Presence at White City. The weeklong Congress on Africa, held earlier in August, brought together leading black intellectuals such as Douglass, Wells, Barnett, and Bishop Henry McNeal Turner, who was famous for asserting that “God is a Negro.” A conference was held on the education of black youth in America. And during the widely covered World’s Congress of Representative Women, which included the suffragists Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and women from around the globe, six African American women spoke about the progress of black women since emancipation. “The exceptional career of our women will yet stamp itself indelibly upon the thought of this country,” promised Fannie Barrier Williams.

While many of the African Americans who were involved with the Fair in some way left their indelible stamp upon history, Douglass and Wells foremost among them, the black presence at the Fair did not. Douglass died two years after the Exposition; Wells made it the launching point of an activist life based in Chicago. A granite boulder and a plaque in honor of Douglass now mark the spot in Jackson Park where the Haitian Pavilion once stood, but many people are unaware that Douglass spent a whole year in this city showing honesty enough, loyalty enough, honor enough, patriotism enough to advocate for his people and show America that it was holding them and itself back with its cruel hypocrisy.