How a Chicago Genre of Music Inspired One of The Biggest Bands in the World

Daniel Hautzinger

March 7, 2018

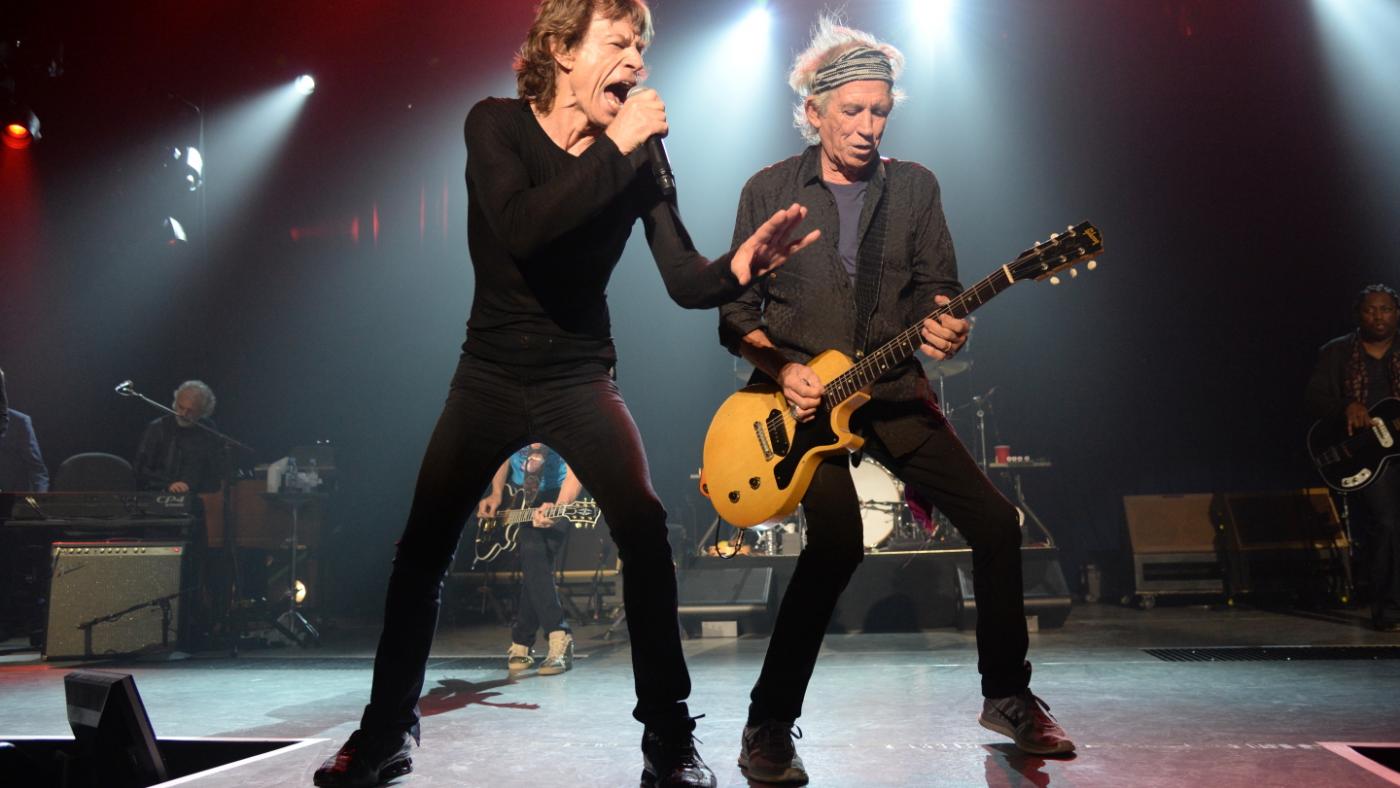

Were it not for a quintessentially Chicago genre of music, one of the biggest bands of the twentieth century may never have formed. The Rolling Stones may be British, but they wanted to sound like black Chicago bluesmen. Keith Richards and Mick Jagger had been longtime casual acquaintances when Richards spotted Jagger at a train station in Dartford, Kent in 1961. What Jagger held in his arms thrilled Richards: records by Muddy Waters and Chuck Berry, special-ordered from Chess Records in Chicago.

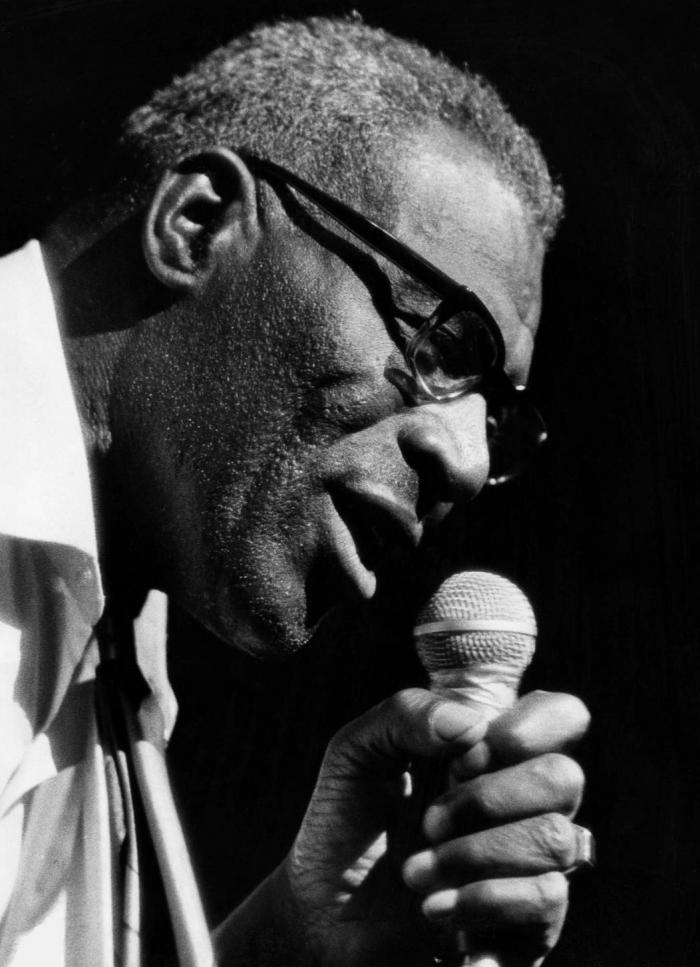

Muddy Waters at Ontario Place, Toronto, June 1978. Photo: Jean-Luc Ourlin via Wikimedia CommonsWaters especially exemplified a style of music called the Chicago blues, which emerged out of the bitter, acoustic laments of the Mississippi Delta. As African Americans moved north in the huge numbers of the Great Migration during the early and mid-twentieth century, many of the bluesmen came too. Once in Chicago, they started electrifying their guitars, adding more grit and fuzz. Although it was mostly ignored by mainstream, white America at the time, some British teenagers latched onto the music, even though few record stores sold it. Jagger and Richards were two of those teenagers, the former learning harmonica from listening to Little Walter, the latter eagerly mimicking the guitar parts on Chuck Berry songs. After the pair discovered their shared love of the niche genre, they eventually joined with another friend, Brian Jones, to form a band devoted to Chicago blues.

Muddy Waters at Ontario Place, Toronto, June 1978. Photo: Jean-Luc Ourlin via Wikimedia CommonsWaters especially exemplified a style of music called the Chicago blues, which emerged out of the bitter, acoustic laments of the Mississippi Delta. As African Americans moved north in the huge numbers of the Great Migration during the early and mid-twentieth century, many of the bluesmen came too. Once in Chicago, they started electrifying their guitars, adding more grit and fuzz. Although it was mostly ignored by mainstream, white America at the time, some British teenagers latched onto the music, even though few record stores sold it. Jagger and Richards were two of those teenagers, the former learning harmonica from listening to Little Walter, the latter eagerly mimicking the guitar parts on Chuck Berry songs. After the pair discovered their shared love of the niche genre, they eventually joined with another friend, Brian Jones, to form a band devoted to Chicago blues.

For their name, they turned to the song “Rollin’ Stone,” by one of their heroes: Muddy Waters. Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon, and other greats all recorded on Chess Records, a label founded by Polish-Jewish immigrant brothers Leonard and Phil Chess in 1947, under the name Aristocrat Records. The Chess brothers sought out talent on the South Side of the city and in the South, selling records primarily to a black audience.

It took British bands like the Stones for the black music of Chicago blues to be accepted by the American mainstream. Many of the band’s early recordings were covers of the artists they loved: their first album featured Dixon’s “I Just Want to Make Love to You” and Jimmy Reed’s “Honest I Do,” and they would soon record songs by Waters, too. As the Stones bassist Bill Wyman told the Chicago Tribune during a tour in 1975, “We just wanted to play Chicago blues for anyone who’d listen to us.”

As the Stones’ popularity exploded, they made sure to continue to emphasize their debt to the Chicago blues. In 1965, when the band appeared on the American TV show Shindig, they brought Waters and Howlin’ Wolf with them. “The Shindig people had no idea who the Stones were talking about,” Buddy Guy recalled to the Chicago Tribune in 1997. “And Mick and Keith were embarrassed that Americans didn’t know who Muddy and Wolf were… The Stones took the Chicago blues to the world.” Later, they would tour with Guy and hire Leonard Chess’s son Marshall to head their own record label.

When they passed through Chicago, they often jammed with their idols. While introducing the Stones at one of those sessions, Waters said, “I’m like a daddy to them.” And, unlike some other British blues-based bands, the Stones passed along royalties to their forebears when they covered their songs, according to both Waters and Dixon.

Two years ago, the Stones once again returned to the music that formed them with their latest album Blue and Lonesome. The record consists entirely of covers of those Chicago blues tunes the young Richards and Jagger loved so much, songs by the musicians they aspired to be: Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon, Little Walter, and others. Fifty years on, they still can’t escape those blues.