Martin Luther King and Fair Housing in Chicago

Daniel Hautzinger

April 11, 2018

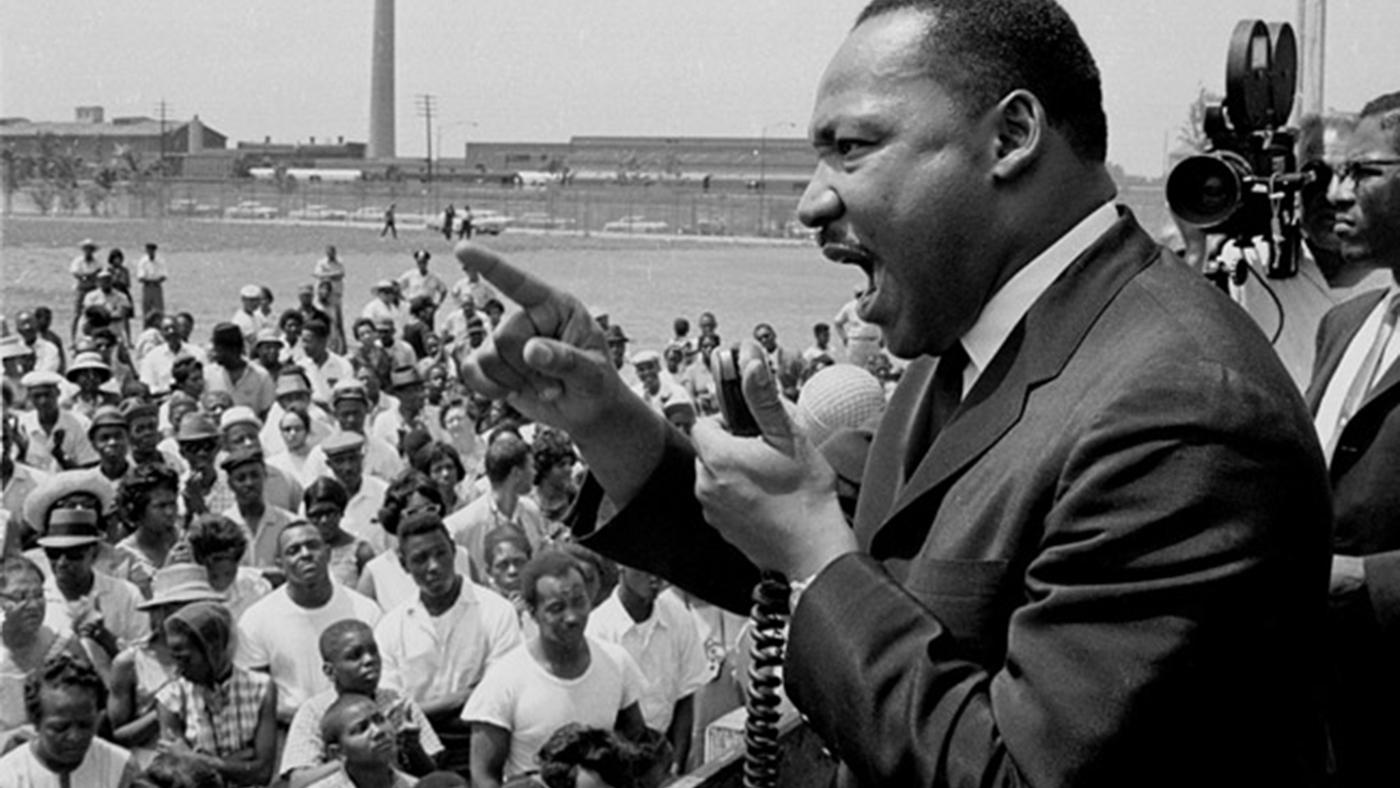

For his first major campaign outside the South, Martin Luther King, Jr. came to Chicago in 1966 to fight discriminatory housing practices, a manifestation of the less blatant but equally pernicious racism of the North. While that campaign ultimately proved disappointing, it helped lead to the passage of the Fair Housing Act in Congress two years later, on April 11, 1968 – 50 years ago today. Despite King’s efforts in Chicago, however, it took his assassination and the ensuing outbreak of riots in cities across the country for open housing to become law.

It was rioting that first turned King’s attention towards the racism faced by African Americans outside the South. In August, 1965, a police incident triggered the Watts Riots in Los Angeles, proving that legal rights alone would not protect blacks from racism. King decided to bring his nonviolent movement to the North and was convinced by Albert Raby and James Bevel, two Chicago activists, that Chicago was the place to start.

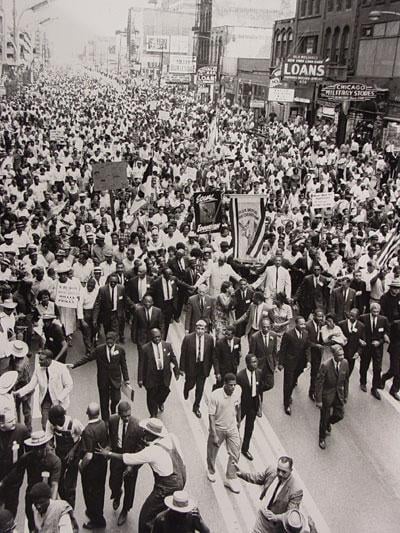

Martin Luther King, Jr. marches along State Street in 1966 as part of the Chicago Freedom Movement. Photo: Chicago Defender ArchivesVarious measures were used across the country to prevent blacks from moving into white neighborhoods during the twentieth century. Restrictive covenants forbade homeowners from selling to blacks (and often other minorities including Jews, Italians, and others) in the first half of the century. They were declared unenforceable by the Supreme Court in 1948 (the playwright Lorraine Hansberry’s family brought an important early case on covenants in Chicago to the Supreme Court), but threats of violence, discriminatorily high prices, and redlining – in which banks refused to finance mortgages in black neighborhoods – kept blacks in ghettos. If an African American family did move into a white neighborhood, unscrupulous realtors would sometimes frighten homeowners into selling their houses, then turn around and sell them to black families for a profit, in a practice known as blockbusting.

Martin Luther King, Jr. marches along State Street in 1966 as part of the Chicago Freedom Movement. Photo: Chicago Defender ArchivesVarious measures were used across the country to prevent blacks from moving into white neighborhoods during the twentieth century. Restrictive covenants forbade homeowners from selling to blacks (and often other minorities including Jews, Italians, and others) in the first half of the century. They were declared unenforceable by the Supreme Court in 1948 (the playwright Lorraine Hansberry’s family brought an important early case on covenants in Chicago to the Supreme Court), but threats of violence, discriminatorily high prices, and redlining – in which banks refused to finance mortgages in black neighborhoods – kept blacks in ghettos. If an African American family did move into a white neighborhood, unscrupulous realtors would sometimes frighten homeowners into selling their houses, then turn around and sell them to black families for a profit, in a practice known as blockbusting.

In order to bring national attention to the despicable housing conditions found on the West Side of the city, King and his wife Coretta moved into a two bedroom flat on the third floor of a building in North Lawndale in late January, 1966. When the landlord learned the identity of his prospective tenant, he sent over a team of contractors to fix up the apartment, but the place was still dilapidated. The neighborhood was dangerous: a notorious gang had been founded a block or so away. Stores in the area, many of which were still owned by white people who had fled the neighborhood, offered low-quality goods and groceries for high prices.

King joined a campaign called the Chicago Freedom Movement, launching a series of efforts in the city. They cleaned up and assumed “trusteeship” of a tenement, redirecting the rent of the residents away from the absentee landlord and towards repairs of the building. They helped form tenants’ unions, led strikes against high rent, worked with local gangs, and boycotted discriminatory businesses.

But the Freedom Movement failed to gain traction. Aware that retaliating against King would make him a martyr and lend the movement support, Mayor Richard J. Daley ensured that the activists weren’t arrested or heckled by police. Daley also responded with his own measures to reform housing, building new units of public housing, slapping code violations on slumlords, and touting vermin eradication campaigns.

Martin Luther King, Jr. after being struck in the head with a rock hurled by a crowd of angry whites during a peaceful march in Chicago's Marquette Park. Photo: Chicago Defender Archives

Martin Luther King, Jr. after being struck in the head with a rock hurled by a crowd of angry whites during a peaceful march in Chicago's Marquette Park. Photo: Chicago Defender Archives

Looking for results, King and the Freedom Movement upped the ante in late July by staging marches into nearby all-white neighborhoods such as Gage Park and Marquette Park. The marchers were met by white counter-protesters who lit the activists’ cars on fire and hurled rocks and bottles. During one march in Marquette Park on August 5, a stone hit King in the head. The marchers were protected by a police escort ordered by Daley, but the violence of the crowd was caught by TV cameras, and popular support turned in favor of King. “I’ve been in many demonstrations all across the South, but I can say that I have never seen – even in Mississippi and Alabama – mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as I’ve seen here in Chicago,” King said.

Daley and other civic leaders opened negotiations with King at the end of August. A non-binding agreement was reached on August 26: King would stop marching, and the city and business leaders would try to make housing more open and fair. Many of King’s supporters saw the agreement as a failure.

But the Chicago Freedom Movement publicized discriminatory housing practices, and fair housing bills began to circulate in Congress. They languished, however, until 1968. Two things changed the tide. First, the Kerner Commission, which had been formed by Lyndon Johnson to investigate the causes of race riots, recommended a fair housing law in a report issued in early 1968. Then, on April 4, King was assassinated in Memphis. Destructive riots broke out in urban areas across the country, including in Chicago, where fires broke out on the West and South Sides, more than 200 buildings were destroyed, and at least nine people were killed.

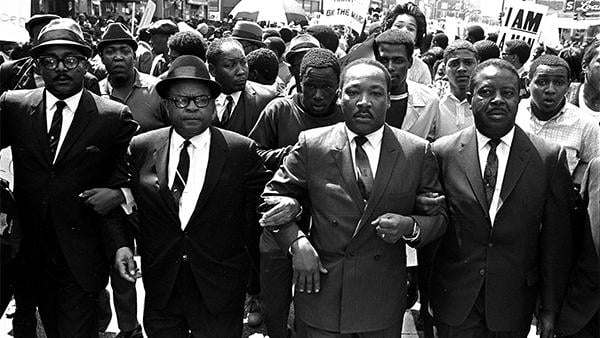

Rev. Ralph Abernathy, right, and Bishop Julian Smith, left, flank Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., during a civil rights march in Memphis, Tenn., March 28, 1968, a few days before King was assassinated. Photo: AP Photo/Jack Thornell

Rev. Ralph Abernathy, right, and Bishop Julian Smith, left, flank Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., during a civil rights march in Memphis, Tenn., March 28, 1968, a few days before King was assassinated. Photo: AP Photo/Jack Thornell

In response to the chaos, on the day after King’s death Johnson urged Congress to pass a fair housing bill. The next day, Daley called Johnson requesting federal troops to help quell the riots. 5,000 came on April 7 (and troops would return to Chicago in just a few months for the disastrous Democratic National Convention). Four days later, on April 11, Congress passed the Fair Housing Act.

Of the two parts of the Fair Housing Act – outlawing real estate discrimination and promoting integration – only the former has ever really been enforced. De jure (legal) segregation is thus ended, but de facto segregation continues, as any Chicago resident knows. Fifty years on, the Fair Housing Act has still not fully achieved Martin Luther King, Jr.’s goal of open housing. (Walter Mondale, one of the co-authors of the Act, wrote an op-ed about its legacy and failures.) In 2015, the Obama administration did adopt a rule that would have required communities to address segregation, but in January of this year the Trump administration delayed its implementation. King’s first campaign in the North has still not been fulfilled.

Find a Chicago Tonight story on the Fair Housing Act here.