The Chinese Exclusion Act and Chicago

Daniel Hautzinger

May 29, 2018

The Chinese Exclusion Act: American Experience is available to stream.

On May 6, 1882, the United States of America – the nation of immigrants – banned an entire nationality from entering its borders or from becoming citizens even if they already resided here. Chinese immigrants had first started coming to America in significant numbers a few decades earlier, during the California Gold Rush, and the Chinese Exclusion Act was a response to rising racist sentiment especially on the West Coast. With a struggling economy and the willingness of hardworking Chinese laborers to take up low-wage work, Californians began blaming the Chinese for the difficult economic circumstances. (This is a common theme in America: during times of economic or political hardship, minorities tend to scapegoated.)

While an initial attempt at banning Chinese immigration was vetoed by President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1878, California passed its own increasingly restrictive laws (one attempt at banning immigration on a state level was struck down by the State Supreme Court), and soon animosity towards the Chinese prevailed on a federal level as well, leading to the passage of the Exclusion Act.

California’s hostility drove many Chinese immigrants eastward, to cities like Chicago, New York, and Boston. Many of these immigrants had worked on the Transcontinental Railroad during the 1870s, which provided a route for them to travel away from the West Coast. Chicago’s first Chinese citizen seems to have been T.C. Moy, who arrived around 1878. Legend has it that his effusive letters about the city to his friends and relatives brought 80 of them to the city within a year. In 1880, the Chinese population was 172; by 1900 it was 1,179.

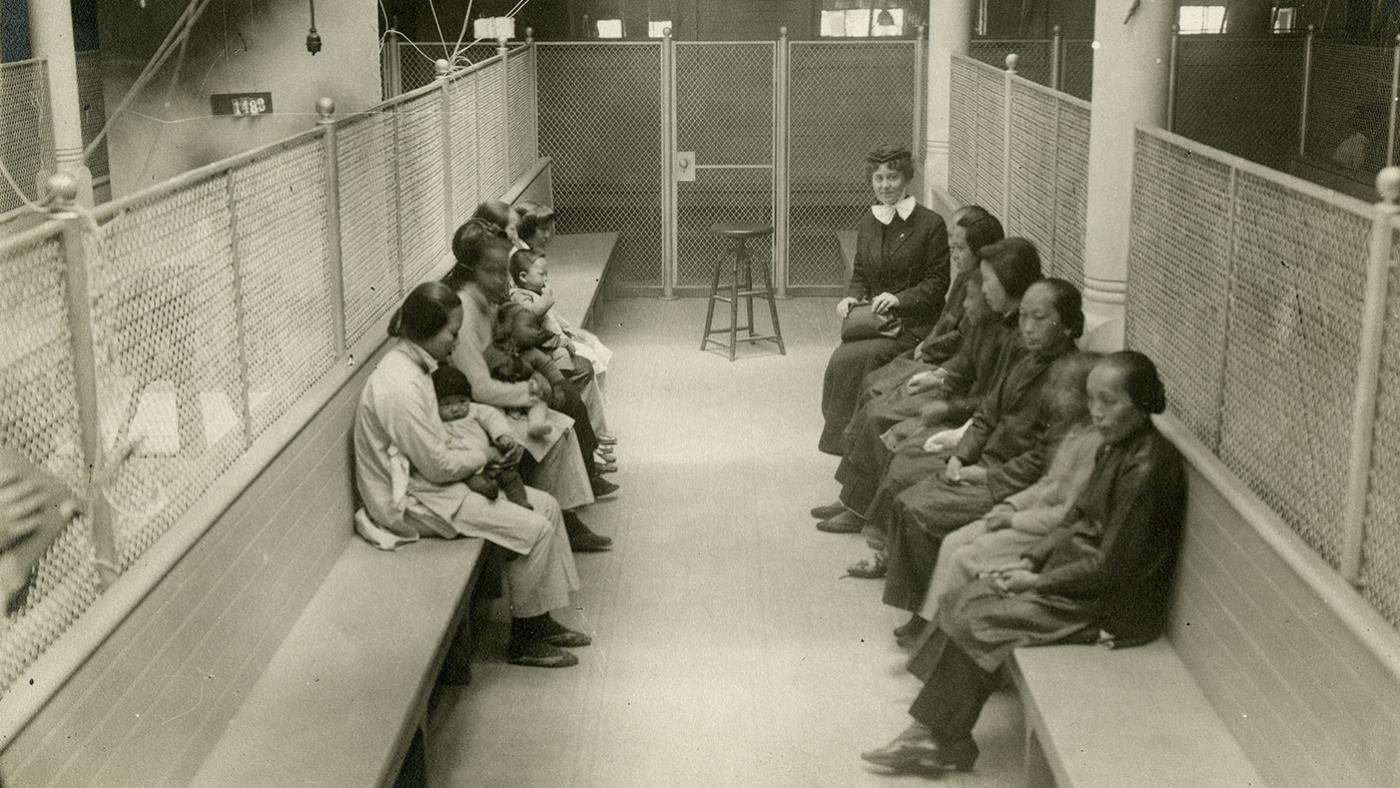

The Chinese Exclusion Act constrained larger growth of Chicago’s Chinese community, not only in its prevention of further immigration and incitement of many immigrants to return to China, but also in its effect on demography. In 1910, of the 1,778 Chinese people in the city, only 65 were women. Nearly the entire Chinese population of Chicago was thus first-generation, and could not expand beyond that.

Even for American-born and -educated families like the Lims, it was difficult to find employment after the Chinese Exclusion Act. Photo: Lim Tong Family Archives

Even for American-born and -educated families like the Lims, it was difficult to find employment after the Chinese Exclusion Act. Photo: Lim Tong Family Archives

Despite the Exclusion Act, Chinese immigrants did continue to come to this country via sub rosa means. People like Tyrus Wong, a Disney illustrator and artist profiled in a recent American Masters special (available to stream by Passport members), and his father circumvented the law by posing as relatives of U.S. citizens, who were allowed to bring relatives over. At San Francisco’s Angel Island, they faced intense, minute questioning about their village and home, designed to suss out these fake relatives, who were known as “paper sons.” And after the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, which destroyed many records, many Chinese immigrants simply claimed that they had been born in San Francisco and their papers had been lost.

While most Chinese Chicagoans dispersed residentially throughout the city in the early decades of their immigration here, they did establish a commercial Chinatown around Clark and Van Buren Streets populated with groceries, restaurants, and family associations. As rents increased, Chinese community leaders began to create a new enclave at Wentworth Avenue and 22nd Place, where Chicago’s Chinatown stands today.

In the 1920s, community leaders erected a striking symbol of their presence in the new Chinatown: the On Leong Chinese Merchants Association Building, which was designed by the same architects who drew up plans for many of the grand field houses in Chicago’s idyllic West Side Parks, such as Garfield, Douglas, and Humboldt Parks. (Across the street stands one of Chicago’s oldest restaurants, Won Kow, which closed this year after ninety years in business.)

With the outbreak of World War II and the attack on Pearl Harbor, anti-Asian sentiment in America found a new target in the Japanese, while China became an ally. In 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Act was finally repealed, though it took until 1965 for other stringent restrictions on immigration to be removed. The Chinese community in Chicago (and the rest of the country) was finally free to grow, and continue to thrive.