Chicago, The "Vatican and Mecca" of Gospel Music

Daniel Hautzinger

June 1, 2018

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.''s The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song premieres and is available to stream Tuesday, February 16 at 9:00 pm. Enjoy a playlist of gospel music from our sister station WFMT. Find out more about Chicago's Black churches at wttw.com/blackchurch.

Chicago is the “Vatican and Mecca” of gospel music, according to the leading gospel scholar Anthony Heilbut, and the religious metaphor perfectly describes the city’s importance in gospel’s history. Mecca is the birthplace of the prophet Muhammad and the site of his first revelation of the foundational text of Islam, the Koran; the spiritual mix of hymns and African American musical traditions we know as “gospel” was first called that in Chicago, and was propagated from here to the rest of the country beginning in the 1930s. And just as the Vatican is the seat of the leader of Christianity, the pope, Chicago was the home of the “Father,” and the “Mother,” the “Queen” and “King” of gospel.

Neither “parent” of the genre was born in Chicago, but both made their careers here. Thomas A. Dorsey, the “father,” moved to Chicago from rural Georgia at the age of 15. Performing as a blues pianist for years, he eventually began writing songs such as “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” that combined blues and jazz with lyrics from traditional spirituals and called them “gospel” music. In the early 1930s, just as these songs – which some viewed as sacrilegious – were gaining traction, Dorsey and Magnolia Lewis Butts were recruited by Theodore Roosevelt Frye to help form a choir at Ebenezer Baptist Church. The pastor there hailed from Birmingham, Alabama, and wanted music more like the spirited congregational singing of the South than the more classical style of black churches in the North. Thus did the first gospel choir come to be.

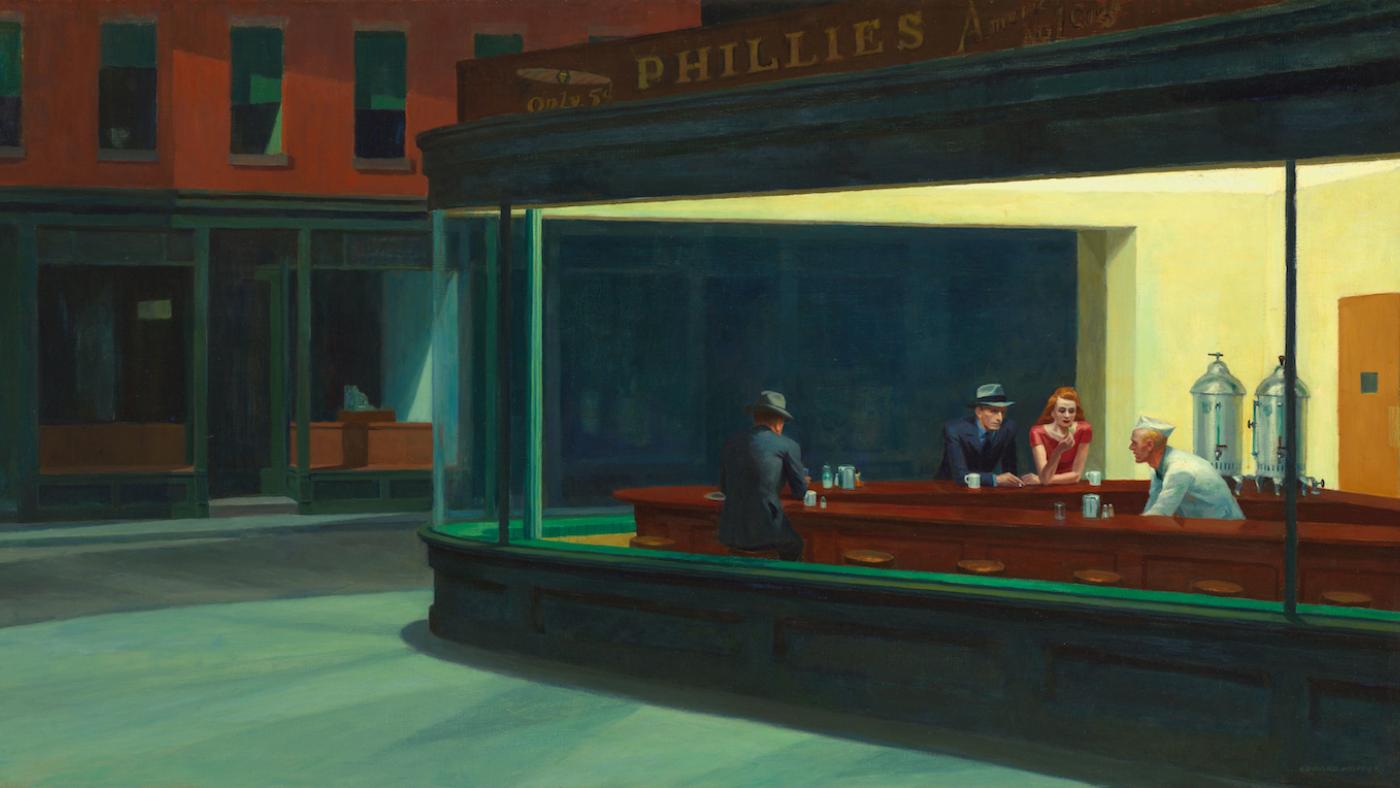

The Chicago Gospel Music Festival. Photo: Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events

The Chicago Gospel Music Festival. Photo: Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events

Soon gospel choirs were forming at other Chicago churches, including one under the direction of Dorsey at Pilgrim Baptist Church (he remained director there for almost 60 years). But were it not for the efforts of Sallie Martin, the “Mother of Gospel,” Dorsey’s music and the new style might never have caught on beyond Chicago. She began singing with Dorsey in 1929 and, for the next decade, she toured with some of his music around the country. More significantly, she convinced Dorsey to publish his songs and marketed them to churches across the States. She even founded a publishing house devoted exclusively to gospel sheet music that became especially famous for publishing “Just a Closer Walk with Thee.” (Dorsey also eventually had his own publishing firm, and Chicago became a center of gospel publishing.)

Martin and Dorsey together founded the American Gospel Convention and the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses, which helped make gospel music a national phenomenon. But it took the “Queen of Gospel” to broaden gospel’s popularity beyond African American church audiences.

Like Martin and Dorsey, Mahalia Jackson was a Southerner who moved north to Chicago during the Great Migration, at the age of 16. After singing a solo at her first Sunday church service in the city, she was recruited for the Greater Salem Baptist Church on the spot. Jackson soon met Dorsey, eventually making his “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” one of her signature songs. In 1948, her recording of “Move On Up A Little Higher” became a massive national hit, revealing the commercial possibilities of gospel music.

Such popular success made many ministers suspicious of Jackson, just as some had been skeptical of Dorsey. They felt her elaborate and soulful vocalizations were more like the blues than praise music. But, despite the commercial potential, she refused to record jazz or pop songs because of her spirituality, and saw a fundamental difference between the blues and gospel: where the blues expressed despair, gospel was an outpouring of hope.

Mildred Falls accompanies Mahalia Jackson, Princess Stewart, and Theodore Frye. Photo: William Russell Jazz Collection at the Historic New Orleans Collection

Mildred Falls accompanies Mahalia Jackson, Princess Stewart, and Theodore Frye. Photo: William Russell Jazz Collection at the Historic New Orleans Collection

Jackson became a worldwide star, moving from the church to the concert hall and touring across Europe. She became the first gospel singer to perform at Carnegie Hall, in 1950, and sang at the inaugural ball of John F. Kennedy. (In between, she gave a special concert in Chicago that was recorded by her friend Studs Terkel, who helped popularize her music on his radio show; you can hear it on our sister station WFMT’s website.) And she became the voice of the civil rights movement, comforting Martin Luther King, Jr. with her hymns, singing at Selma and the March on Washington, inspiring King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, and blessing King’s funeral with song.

And then there came the “King of Gospel,” whose trajectory was the reverse of the “Mother,” “Father,” and “Queen.” The Rev. James Cleveland was born in Chicago, beginning his singing life at Pilgrim Baptist under Dorsey, but made his career outside the city. For a while, he worked as a music director in Detroit at the church of Rev. C. L. Franklin, living at Franklin’s home and teaching his daughter, a young girl named Aretha, to sing gospel. He later moved to Los Angeles, shifting gospel’s center away from Chicago along with him. It was there that he incorporated more soul and pop elements into his gospel songs and arrangements, performing with the “fifth Beatle” Billy Preston and producing his Detroit protégé Aretha Franklin’s Grammy-winning album Amazing Grace.

The changing trajectory of gospel – its increasing use of electric instruments and popular music styles, the move of its epicenter from Chicago to California – is encapsulated by one of Cleveland’s achievements: he was the first gospel performer to receive a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame. Gospel may have achieved glitz and glamour, but its spiritual heart – its Mecca and Vatican – are still in Chicago.