The Harlem (Actually Chicago) Globetrotters

Daniel Hautzinger

June 6, 2018

The name “Harlem Globetrotters” conjures up a certain origin story: quick-handed, hot-footing, joke-busting kids are discovered goofing and shooting hoops on some cracked concrete court in the New York City borough, then whisked to sudden fame in cities around the world on the basis of their awesome tricks and mugging comedy. But the name is deceiving. The Globetrotters actually started when five South Side Chicagoans teamed up with a 5’3” Jewish guy to play basketball games in the local gyms of small-town Illinois.

The five players were graduates of the renowned basketball program at Wendell Phillips High School, and wanted to play semi-pro. Somehow they came in contact with Abe Saperstein, a North Sider who loved sports and worked as an athletic director in the Chicago Parks System. In 1926, Saperstein became their manager (and substitute player, if someone got injured), and the team set off to play in nearby towns such as Hinckley, Illinois. They had a winning record of 101-6 in their first full season.

In 1928, the fledgling team finagled a residency at the new Savoy Ballroom in Bronzeville, where musicians such as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington played. There they became the Savoy Big Five, but Saperstein and several of the players quickly left after a dispute over money and once again rebranded themselves, as the Harlem Globetrotters. The name was a marketing gimmick concocted by Saperstein: “Globetrotters” made it sound as if they had an international schedule, and “Harlem” denoted the center of African American culture, telegraphing the makeup of the team to his small-town white audiences, many of whom had never seen black basketball players before.

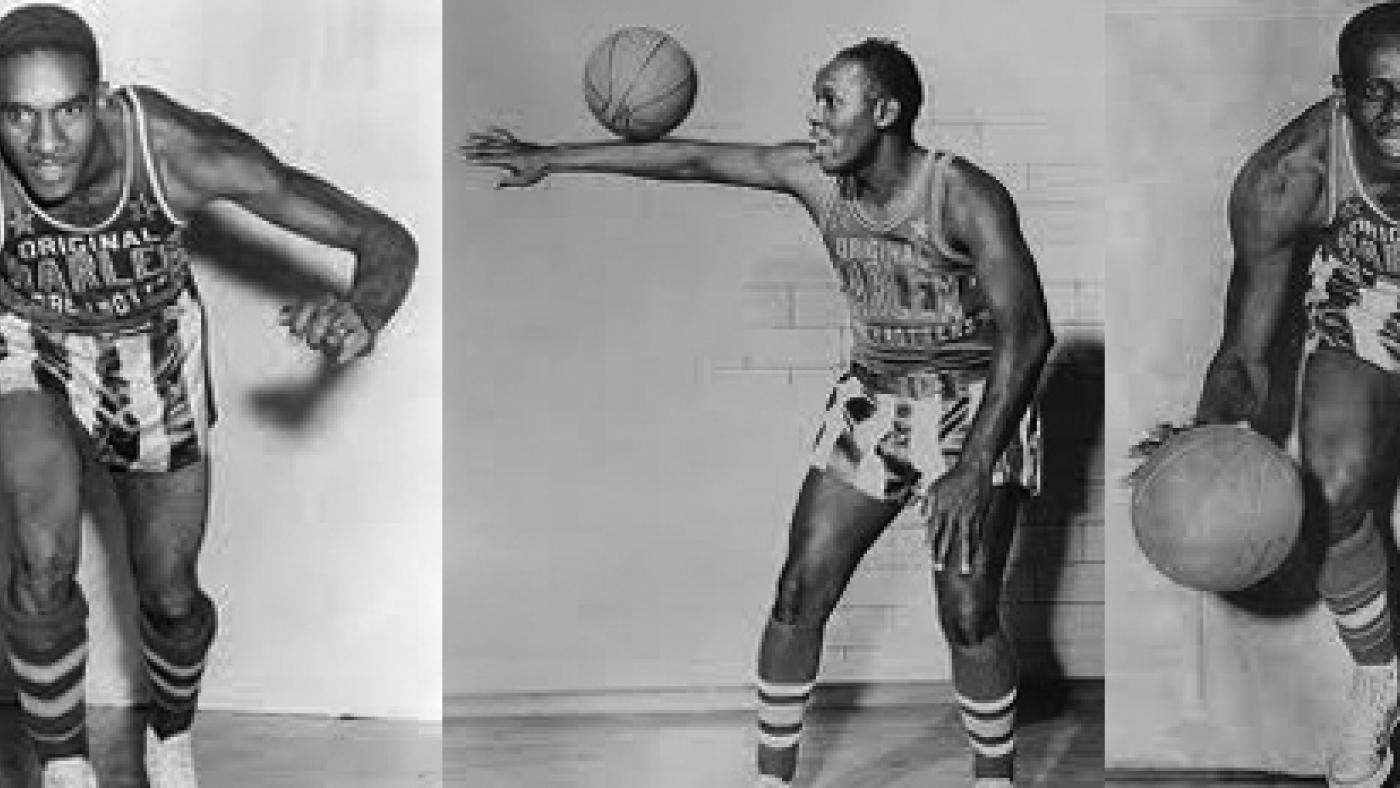

The world-traveling, internationally known Globetrotters of today are very different from the team at its beginning

The world-traveling, internationally known Globetrotters of today are very different from the team at its beginning

Those same audiences, surprised and delighted by the Globetrotters’ fast-break style, often shunned the black players after the game, despite the joy they got from watching them play. As the team gained popularity, it also grew in skill. The barring of African Americans from the professional basketball leagues meant the Globetrotters had their pick of black talent, and signed such players as the clowning “Goose” Tatum and fleet Marque Haynes, who eventually became the first Globetrotter to be inducted to the Basketball Hall of Fame.

The team’s skill eventually led them to win the World Professional Basketball Tournament in 1940, and then to beat the best team in the all-white precursor to the NBA in 1948. The following year, two leagues merged to form the NBA, yet still professional basketball remained unintegrated, despite the talent evinced by the Globetrotters and other black players. (Jackie Robinson broke the color line in baseball in 1947.)

Then in 1950, the Boston Celtics drafted Chuck Cooper as well as Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton, who played for the Globetrotters, and professional basketball started to integrate. Rumor has it that Saperstein had a deal with the NBA in its first years to keep the best black players for the Globetrotters to ensure that the NBA would remain all-white.

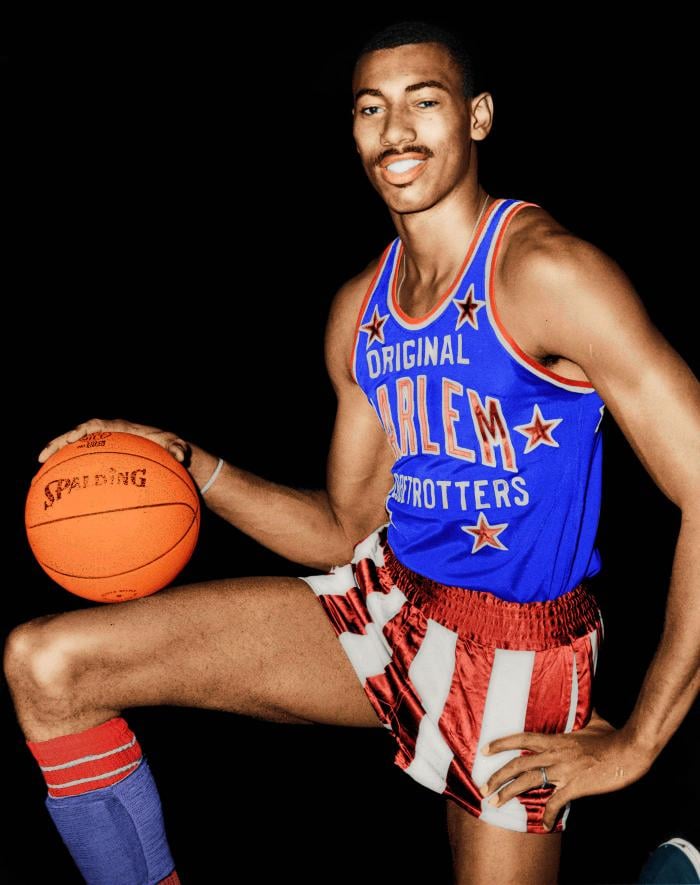

Wilt Chamberlain played one season for the Globetrotters, which he called the happiest year of his lifeAnd there have been other muted accusations of racism – or at least exploitative business practices – against Saperstein, such as disputes with players over wages. Especially in the ‘60s, the Globetrotters began to be criticized by some in the black community for being Uncle Toms, degrading themselves as buffoonish minstrels for the entertainment of white people.

Wilt Chamberlain played one season for the Globetrotters, which he called the happiest year of his lifeAnd there have been other muted accusations of racism – or at least exploitative business practices – against Saperstein, such as disputes with players over wages. Especially in the ‘60s, the Globetrotters began to be criticized by some in the black community for being Uncle Toms, degrading themselves as buffoonish minstrels for the entertainment of white people.

But the team also did offer some valedictory moments for African Americans, as on a 1951 trip to Germany. The track star Jesse Owens, who had won gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Olympics but was snubbed by Hitler, occasionally helped promote the Globetrotters. Saperstein invited him to a game in 1951, and he was welcomed there by the mayor of Berlin, who embraced him, saying, “In 1936, Hitler refused to give you his hand. Today I give you both of mine.”

The Globetrotters continued to incubate talent – Wilt Chamberlain played with them for one season, which he called the happiest year of his life – and grow in popularity, traveling to more than80 countries. In 1966, Saperstein died of a sudden heart attack, and the team was sold. In 1976, the team moved its base from Chicago. By the ‘80s, despite television shows, it was declining, and in 1993 it was bought again, this time by a former player: Mannie Jackson, who became the first African American to own a major sports franchise. Jackson revitalized the franchise with a new emphasis on competitive games as well as corporate marketing deals.

And thus the Chicago team with a New York name continues to this day.