"Respect Yourself": The Power of The Staple Singers

Daniel Hautzinger

June 8, 2018

Sears and Roebuck grew up on a plantation in the Mississippi Delta, but when Roebuck was 21 he left his brother and moved to Chicago, the city that headquartered their namesake. There he begat a brood of melodious children, naming one of them after not a mail-order company like himself but a songbird, perhaps having had a premonition of Mavis’s fantastic deep voice. The children sat in a circle on the floor and learned the harmonies Pops – that’s what they called him – gave them, and soon their voices were ringing out in churches, then in halls, then at civil rights marches, until the whole country knew this band of vividly named musicians – Pops, Mavis, Cleotha, Pervis, and Yvonne Staples – as simply The Staple Singers.

The Staples performed songs that combined the influences of Pops’ birthplace and adopted home: the Delta blues of legends like Charley Patton, who often played outside the general store near Pops’ Mississippi home, and the uplifting gospel that grew out of the churches of Chicago. After all, the two genres aren’t too far apart, as Rev. Jesse Jackson points out in this clip from a 2002 episode of WTTW’s Chicago Stories about The Staple Singers (you can also hear their friends Harry Belafonte and Bob Dylan reflecting on Mavis, Pops, and the Staples in the clip):

Pops’ first job in Chicago, after he arrived in 1935, was in the stockyards, where he made four cents a day shoveling fertilizer and working the hog-kill. At home, at 506 E. 33rd Street, he taught his children to sing and harmonize. Their first performance was at Mount Calvary Baptist Church, where they sang “If I Could Hear My Mother Pray Again” three times – it was the only song they knew, but the crowd kept calling them back for encores.

After gaining popularity in churches around Chicago – and learning more songs – the Staples were signed by local record label Vee-Jay and had their first hit in 1956 with “Uncloudy Day,” which featured signature elements of their sound: Pops’ tremolo guitar, Mavis’s unearthly voice, and her siblings’ harmonies. A young Bob Dylan was entranced by the song, calling it “the most mysterious thing I’d ever heard… [Mavis’s] singing just knocked me out.”

And Dylan wasn’t the only prominent fan. As the civil rights movement took off in the 1960s, the Staples became involved with and befriended Martin Luther King, Jr. Pops had always fought against segregation, refusing to eat in the backs of restaurants in the South. (Instead, the Staples would make sandwiches in their car when on tour.) So when he heard Dr. King preach in Montgomery, Alabama in 1963, he decided to begin to write “message songs.” As he told his children after hearing King’s sermon, in Mavis’s recollection, “Listen you all, I really like this man’s message. And I think that if he can preach that, we can sing it.”

Thus came songs like King’s personal favorite “Why? (Am I Treated So Bad),” “I’ll Take You There,” and “Respect Yourself.” The Staple Singers traveled with King, performing concerts to raise money for the civil rights movement. And Pops encouraged other songwriters to write music that addressed the times, too: “If you want to write a song for us, read the headlines,” he’d tell them.

Greg Kot's biography of Mavis Staples is the current selection for "One Book, One Chicago"In the late ‘60s, the Staples signed with Stax Records in Memphis, where they incorporated more contemporary soul influences such as a grooving rhythm section. (Just listen to that buoyant bass line on “I’ll Take You There.”) They continued to record into the 1980s, garnering countless fans, from the Jackson 5 to Natalie Merchant to Bebe Winans.

Greg Kot's biography of Mavis Staples is the current selection for "One Book, One Chicago"In the late ‘60s, the Staples signed with Stax Records in Memphis, where they incorporated more contemporary soul influences such as a grooving rhythm section. (Just listen to that buoyant bass line on “I’ll Take You There.”) They continued to record into the 1980s, garnering countless fans, from the Jackson 5 to Natalie Merchant to Bebe Winans.

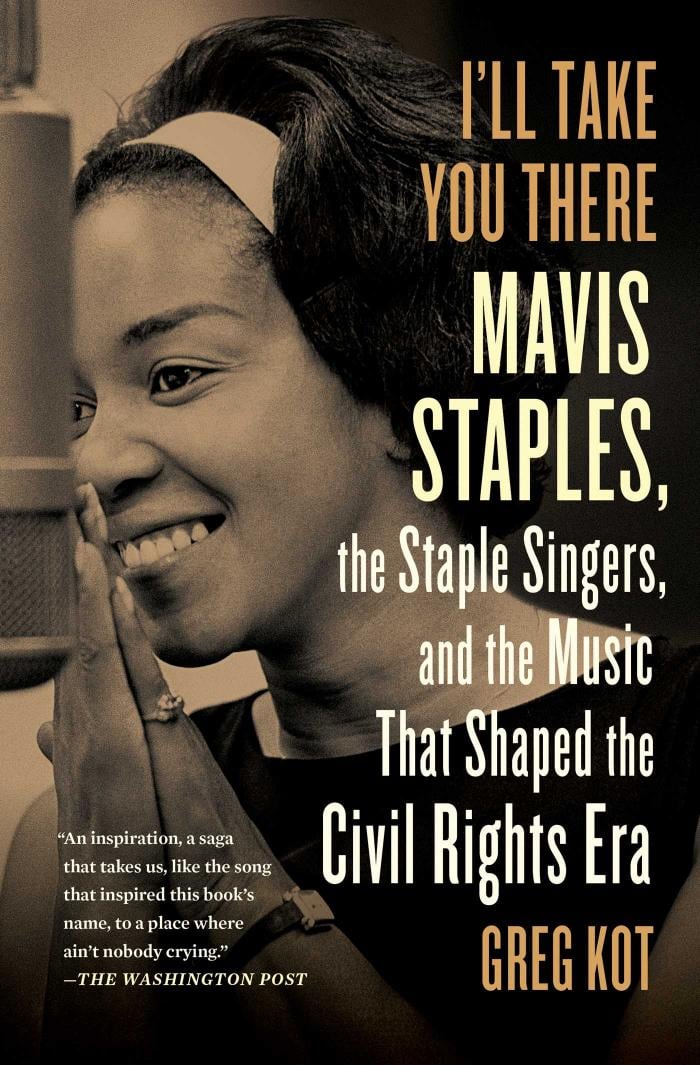

Mavis has had a late-career blossoming in the 2010s, with a slew of albums produced by Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy as well as guest appearances on songs by Arcade Fire and Gorillaz, among others. She’s the headliner of this year’s Chicago Blues Festival, where she performs on Sunday, June 10 at Millennium Park’s Jay Pritzker Pavilion, even though she turns 79 next month. The journalist Greg Kot’s biography of her, I’ll Take You There, is the Chicago Public Library’s current “One Book, One Chicago” selection. Harry Belafonte would probably extend what he said of her family’s group in the 2002 Chicago Stories episode to Mavis today: “When you listen to The Staple Singers, I think you hear black art at its finest, finest expression.”