What the Bahá’i Temple Reveals About the Bahá’i Faith

Daniel Hautzinger

August 15, 2018

On the shore of Lake Michigan, north of Chicago, there is a wondrous white temple that welcomes all religions yet does not have clergy, a congregation, or even formal worship services beyond brief prayer gatherings. In the lacy arabesque panels that decorate its minaret-like columns you can find hooked crosses symbolizing Buddhism and Hinduism, Stars of David for Judaism, Christian crosses, Islamic crescent moons, and a nine-pointed star. If the last symbol is unfamiliar, that’s because it represents the youngest of those religions, and the motivating force behind the temple: the Bahá’í Faith.

The columns on the Bahá’i temple display symbols from various religions. Photo: Courtesy of the US Bahá’í National CenterThe Bahá’í House of Worship in Wilmette is sometimes called the “silent teacher” for the way that it illustrates principles of the faith. Its most majestic and visible feature, its soaring dome, symbolizes the core belief of Bahá’ís: the oneness of humanity under a single God. The ribs arching over that dome represent the hands of global peoples clasped in prayer. “The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens,” says an inscription on the temple’s exterior.

The columns on the Bahá’i temple display symbols from various religions. Photo: Courtesy of the US Bahá’í National CenterThe Bahá’í House of Worship in Wilmette is sometimes called the “silent teacher” for the way that it illustrates principles of the faith. Its most majestic and visible feature, its soaring dome, symbolizes the core belief of Bahá’ís: the oneness of humanity under a single God. The ribs arching over that dome represent the hands of global peoples clasped in prayer. “The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens,” says an inscription on the temple’s exterior.

Bahá’ís do not reject other religious teachings but instead believe that God has been progressively revealed through the ages by a series of divine messengers that includes Krishna, Abraham, Moses, Zoroaster, Buddha, Jesus, and Muhammad – hence the use of diverse religious symbols in the ornamentation on the House of Worship. Each of these “Manifestations of God,” as the Bahá’ís call them, has offered teachings that fit the conditions of their time and place. While their social teachings – such as what to eat, how to pray, or how to inter bodies – may change, certain spiritual tenets are universal, for instance, love and respect your neighbor. As one of the inscriptions inside the temple says, “All the Prophets of God proclaim the same faith.”

Therefore, Bahá’ís accept and even study the teachings of other religions, but believe that two new divine messengers appeared in Persia during the 19th century. Bahá’u’lláh, whose name means “the Glory of God,” is the founder of the faith, while the Báb (“Gate”) prophesied Bahá’u’lláh’s coming. Bahá’is believe that their faith, as the most recent expression of God in this lineage of revelations, is suited for our own time of globalization, in its preaching of oneness.

The Bahá’i temple north of Chicago is the oldest standing Bahá’i House of Worship. Photo: Courtesy of the US Bahá’í National CenterThe Bahá’í faith spread from Persia despite persecution – the Báb was executed by firing squad in 1850 while Bahá’u’lláh was imprisoned and exiled for much of his life – and was first presented in America by the Christian minister Henry Jessup during Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Jessup had encountered the fledgling faith while traveling in the Middle East, and introduced it here at the World's Parliament of Religions. It grew quickly in this country, and by 1903 American Bahá’ís wanted to build a House of Worship in the United States, having been inspired by plans to build the first Bahá’í temple in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan. (That House of Worship was demolished in 1963 after being critically damaged in an earthquake.)

The Bahá’i temple north of Chicago is the oldest standing Bahá’i House of Worship. Photo: Courtesy of the US Bahá’í National CenterThe Bahá’í faith spread from Persia despite persecution – the Báb was executed by firing squad in 1850 while Bahá’u’lláh was imprisoned and exiled for much of his life – and was first presented in America by the Christian minister Henry Jessup during Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Jessup had encountered the fledgling faith while traveling in the Middle East, and introduced it here at the World's Parliament of Religions. It grew quickly in this country, and by 1903 American Bahá’ís wanted to build a House of Worship in the United States, having been inspired by plans to build the first Bahá’í temple in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan. (That House of Worship was demolished in 1963 after being critically damaged in an earthquake.)

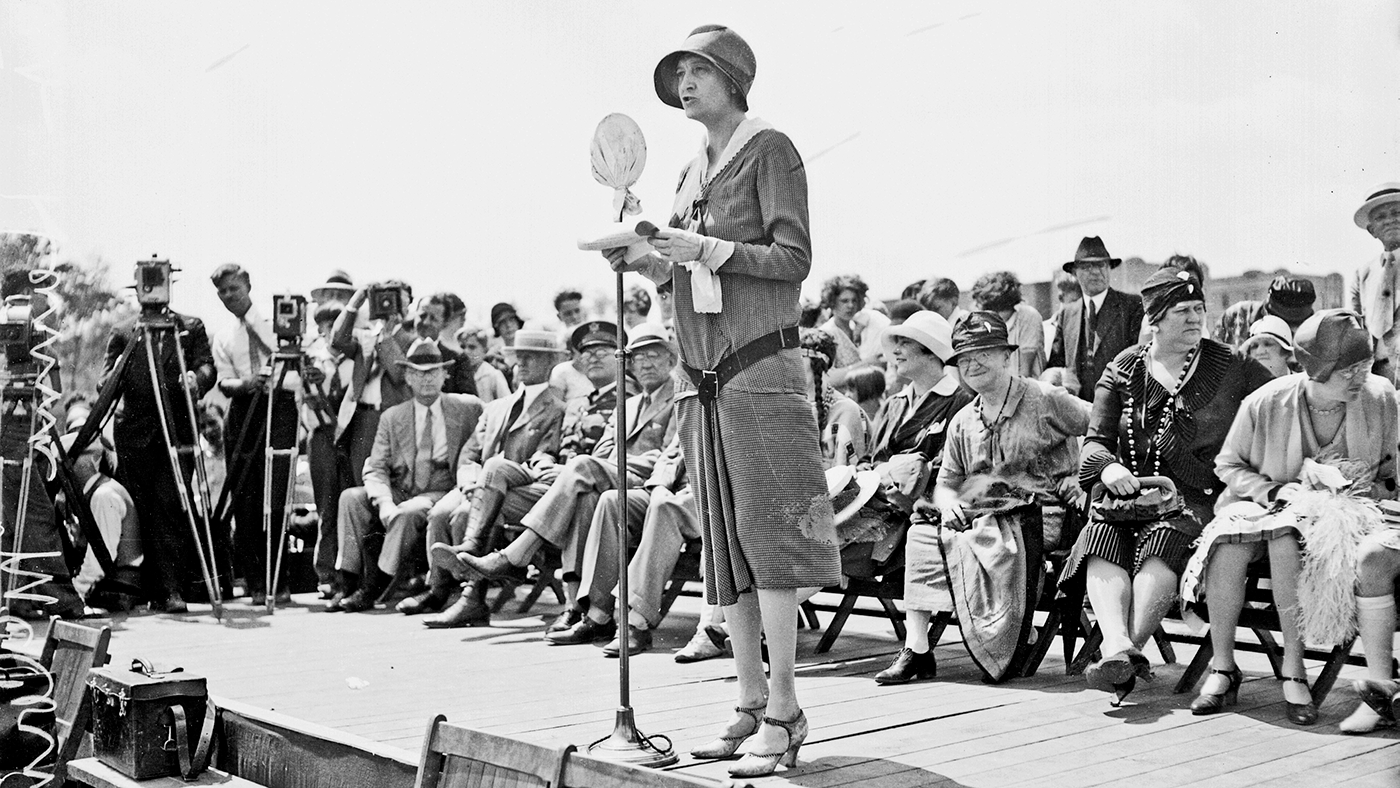

The American Bahá’í community decided to locate the House of Worship in Chicago, given the city’s position at the heart of the country, and purchased property on the lake in 1907. Women such as Corinne True, known as the “Mother of the Temple,” took the lead in planning and raising money for the project, in an arrangement unusual for the time but representative of the Bahá’í belief in the equality of men and women. In 1920 a design by the French-Canadian architect and Bahá’i Louis Bourgeois was chosen for the House of Worship.

Bourgeois had worked with the prominent Chicago architect Louis Sullivan and studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and his design reflected the influence of both. The Beaux-Arts style, which became popular in Chicago at the 1893 Columbian Exposition and can be seen in such buildings as the Art Institute, Cultural Center, and Museum of Science and Industry, prized symmetry, lots of decoration, and stone, while Sullivan was known for his botanical ornamentation and steel-frame construction.

The House of Worship incorporates all of this, in its use of highly ornamented concrete panels hung on either side of a steel superstructure, with glass to keep out the elements. In another nod at the oneness of humanity, the design includes architectural elements from various traditions, such as Gothic arches and Islamic arabesques. But Bourgeois’s ornate vision required some technological innovation – not an obstacle for Bahá’is, who believe that to reconcile science with faith is to know truth.

The Bahá’i temple consists of a steel superstructure on which ornate pre-cast concrete panels are hung. Photo: Courtesy of the US Bahá’í National Center

The Bahá’i temple consists of a steel superstructure on which ornate pre-cast concrete panels are hung. Photo: Courtesy of the US Bahá’í National Center

A stone carver named John Earley had been experimenting with pre-cast concrete, which provided a means to enact Bourgeois’s vision. After creating the panels in his workshop in Rosslyn, Virginia, Earley shipped them by rail to Wilmette to be hung on the steel superstructure. And he made the plain white concrete beautiful by mixing in crushed quartz, which catches the light and sparkles. For Bahá’is value beauty, viewing it as proof of God. This principle is further illustrated in the nine different gardens surrounding the House of Worship.

The number nine is significant in the Bahá’i faith, symbolizing unity, perfection, and completion as the highest single digit. Just as there are nine gardens, the House of Worship has nine sides and nine doors. Nine is present in the symbol of the nine-pointed star and in the number of people who make up Bahá’i governing assemblies. And the temple has 18 steps leading up to it (double nine), and 45-foot columns (five times nine).

The nine gardens surrounding the Bahá’i temple are indicative of the Bahá’i's love of beauty and belief that there is unity in diversity. Photo: Courtesy of the US Bahá’í National Center

The nine gardens surrounding the Bahá’i temple are indicative of the Bahá’i's love of beauty and belief that there is unity in diversity. Photo: Courtesy of the US Bahá’í National Center

The Wilmette House of Worship serves as the mother temple for all of North America, and is the oldest standing House of Worship, having finally opened after decades of construction in 1953. Seven other “continental” temples exist, each incorporating local design elements but conforming to the common schematic of a nine-sided structure surrounded by gardens and surmounted by a single dome. (There is also a House of Worship that opened last year in Cambodia, the first Bahá’i temple to serve a local area rather than a whole region.)

Yet these Houses of Worship are not the home of any congregation. The Wilmette Bahá’i community, which numbers only around 60 people, does not gather in the temple. Rather, the House of Worship is intended to be a common meeting place for all peoples, of any faith or no faith, and as such is open to the public. Regardless of belief, a site that encourages unity and fellowship between all peoples is an important thing in these divided times. And what a magnificent meeting place.