How Volunteers Help Improve the Quality of Life for Women in Prison Through Books

Daniel Hautzinger

August 16, 2018

“It is so hard getting to our library,” reads one note. “I have gone 3 weeks now without a book.” The letter was written to Chicago Books to Women in Prison, and it demonstrates the necessity of the volunteer-run, donation-driven nonprofit in stark terms. Despite what you might see on TV, prison libraries are often poorly stocked – last year, the Illinois Department of Corrections spent a mere $276 on books for educational programming – and access can be extremely limited, as the incarcerated woman’s letter makes clear.

Chicago Books to Women in Prison (CBWP) addresses that need by doing exactly what its name says: sending packages of donated books to state prisons in seven states, including Illinois, and federal prisons in 12 states, plus the Cook County Jail. Last year they mailed 4,690 packages, around 12,000 books. It’s one of a few dozen books-to-prisoners projects across the country, but one of only two that focus on women. While women make up a relatively small proportion of the prison population in the United States – in 2017, there were around 219,000 incarcerated women as compared to a total incarcerated population of more than 2.3 million people, according to a report by the nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative – the needs and concerns of women in prison often differ from those of men, says Vicki White, the volunteer president of CBWP.

More than half of women in prisons – and 80% of women in jails – are mothers, and the majority were the primary caretakers of their children before their arrest. “So we make a point of stocking books on parenting, including books on parenting in prison,” Vicki says of CBWP. “Books like that are really critical to alleviate a woman’s concerns or might give her some practical information about what she can do while she’s in prison to strengthen that bond and become a better parent.” And the damage of incarceration is not limited to the mother; there are various known harmful effects on children resulting from having a parent in prison.

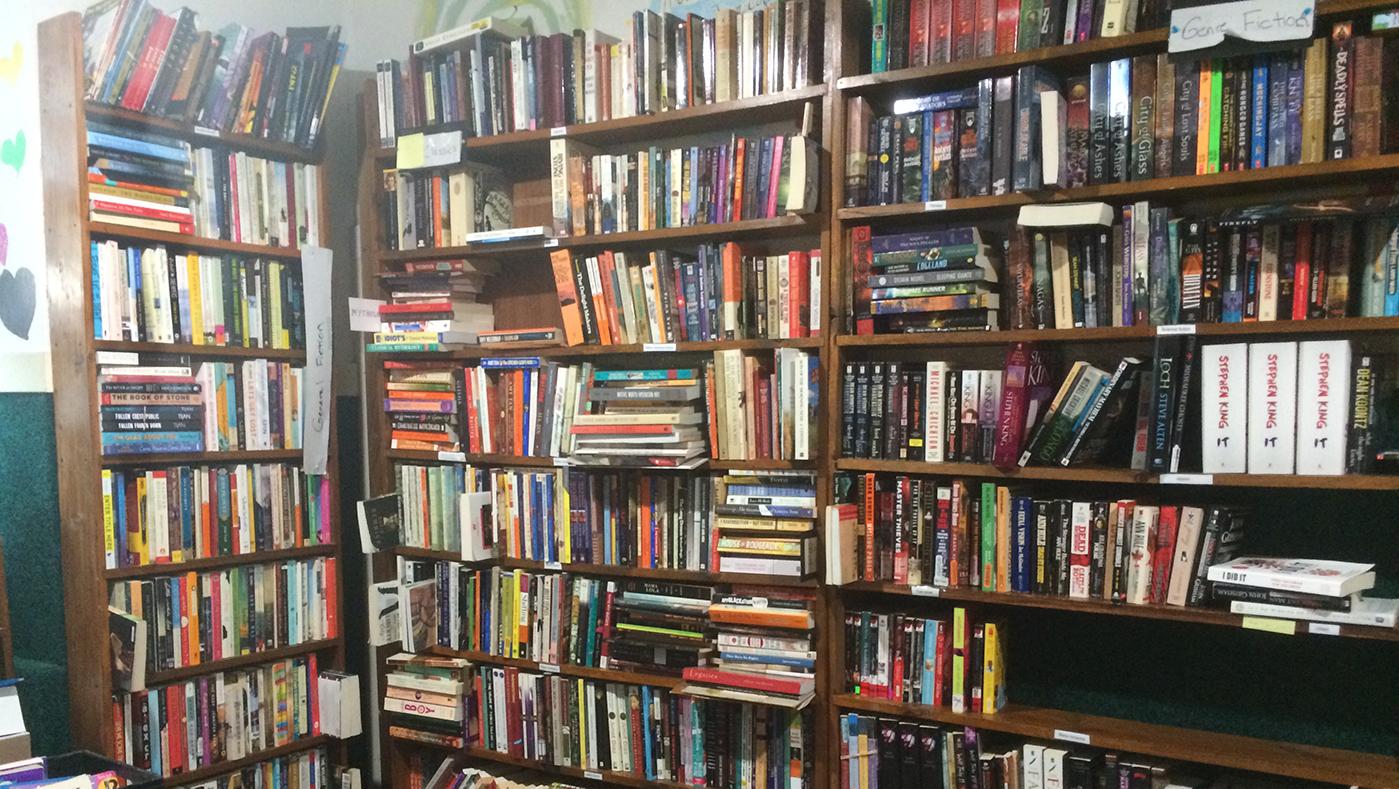

But volumes on parenting are obviously not the only books that CBWP sends out. Women request books from CBWP directly, either filling out one of the organization’s order forms or sending requests on any scrap of paper. Two afternoons every week, the volunteers at CBWP search through their stock of donated books in the narrow, muggy basement rooms that they rent from a Ravenswood church, in order to match requests. While they can’t always send specific titles, they put a lot of thought into substitutions, based upon a woman’s other requests or genre preferences. A volunteer named Julie, who came to CBWP because she was horrified by the idea of not having access to books, emphasized the pleasant challenge of selecting books that the woman will enjoy – “It feels like giving people presents,” she says. For this reason, CBWP likes to say that they are “fulfilling requests,” rather than “packing books;” it’s more personal.

CBWP then sends out a package with three books, a new order form, and a short personal note that might explain a book substitution. Because of the volume of requests, women only receive books every three to five months. But the books have a “multiplier effect,” as Vicki calls it, often being shared with bunkmates, left on a bookcase in a living unit if there is one, or even contributed to the prison library itself. One formerly incarcerated woman told Vicki that someone once gave her a book that she herself had received from a friend some ten years earlier – it had been passed between women for a decade.

Women request a wide range of books, from dictionaries to true crime, puzzle books to religious materials, urban books to self-help to accounting to welding to romance. (Find a list of CBWP’s most commonly needed books and learn how to donate here.) “We joke that any book that you think no one would ever read, we’ll get a request for,” says a volunteer named Karen. She used to work in a bookstore, but says she has learned more about books volunteering at CBWP than she did at the shop, because of all the subgenres and categories she herself might never have otherwise encountered. To make sure that CBWP receives those types of unusual books – how to train sheep, for example, or, more prosaically, GED Review books – they also have an Amazon wish list from which you can donate books. (They also accept financial support through PayPal, as well as volunteers, though there is currently a waiting list to be trained.)

To learn more about unfamiliar genres in order to better fulfill requests, the volunteers of CBWP have organized reading challenges over the summer to read and discuss them, so that they can understand what a woman who requests those types of books is looking for. Putting so much thought into fulfilling the requests adds an extra dimension of worth to CBWP’s endeavor, as Karen points out: “These women can’t pick what they wear, or where they go, and they often aren’t even called by their name, so to have someone say, ‘I thought really hard about you personally’ is really important.”

Plus, books can benefit not only the women but their families and communities. “By helping women have a better quality of life while in prison – helping them achieve their educational goals, helping them stay sane, become stronger to the extent that they can – that’s just better for their family and the community they’ll be returning to,” says Vicki.

The incarcerated women often want to help each other, too. Some enclose a stamp or two with a thank you letter, to enable another shipment of a package of books, despite their often very limited means. (Jobs in Illinois state prisons pay from $0.09 to $0.89 an hour.) Vicki says one woman would even occasionally have a check cut so that she could donate to CBWP, even if it was $3.

And then there was the woman who had requested a guide to getting published. After receiving it, she wrote back to CBWP about her hope to become a published author. “Wouldn’t it be amazing,” she wrote, “to have [my books] available to other participants of the book program?”