The Story of the Iconic Chicago Home

Daniel Hautzinger

January 3, 2019

We often hear about the white-picket-fence suburban home as the epitome of the mid-to-late twentieth century American Dream, but there was an earlier exemplar of middle-class American – specifically Chicagoan – striving: the bungalow. From about 1910 until 1940, that style of narrow, squat home sprouted up around the edges of Chicago by the tens of thousands as families sought to leave behind the crowded neighborhoods and apartments of the city center and buy their own home with a yard. As Chicago rapidly expanded, so too did the “Bungalow Belt,” a crescent-shaped strip of neighborhoods filled with bungalows that girded the city from the Northwest Side down through Belmont Cragin and Marquette Park to South Chicago. There are more than 80,000 bungalows in Chicago, making up about a third of the single-family homes in the city.

The name “bungalow” comes from “bungla,” a type of housing built for British colonials in England. While it can describe a variety of different home types, there is a style specifically adapted to Chicago that anyone who has lived here will probably recognize: a long and skinny, one-and-a-half story brick home with a basement and elevated porch, often graced with substantial windows in the front, perhaps including a dormer window peeking out from the roof on the second floor. This style was first built around 1910 and soon took off as an affordable home design as developers eagerly bought groups of lots and erected bungalows to sell to the families of the expanding middle class, following the extensions of streetcar lines and main roads out of the city. By the 1920s, the Chicago bungalow was so popular that few other styles of moderately priced homes were being built in the city.

Bungalows were desirable not just because they were an affordable house that included a yard, but also for their craftsmanship and conveniences. New methods of production allowed for the cheaper manufacture of aesthetically prized features such as simple, varnished wood trims, leaded art glass windows, and built-in bookcases, as well as kitchen and bathroom fixtures. Unlike older housing stock, bungalows had indoor plumbing, electric instead of gas lights, and central heating via radiators. While most adhered to a standard floor plan, facades differed slightly by means of different colored bricks or patterns.

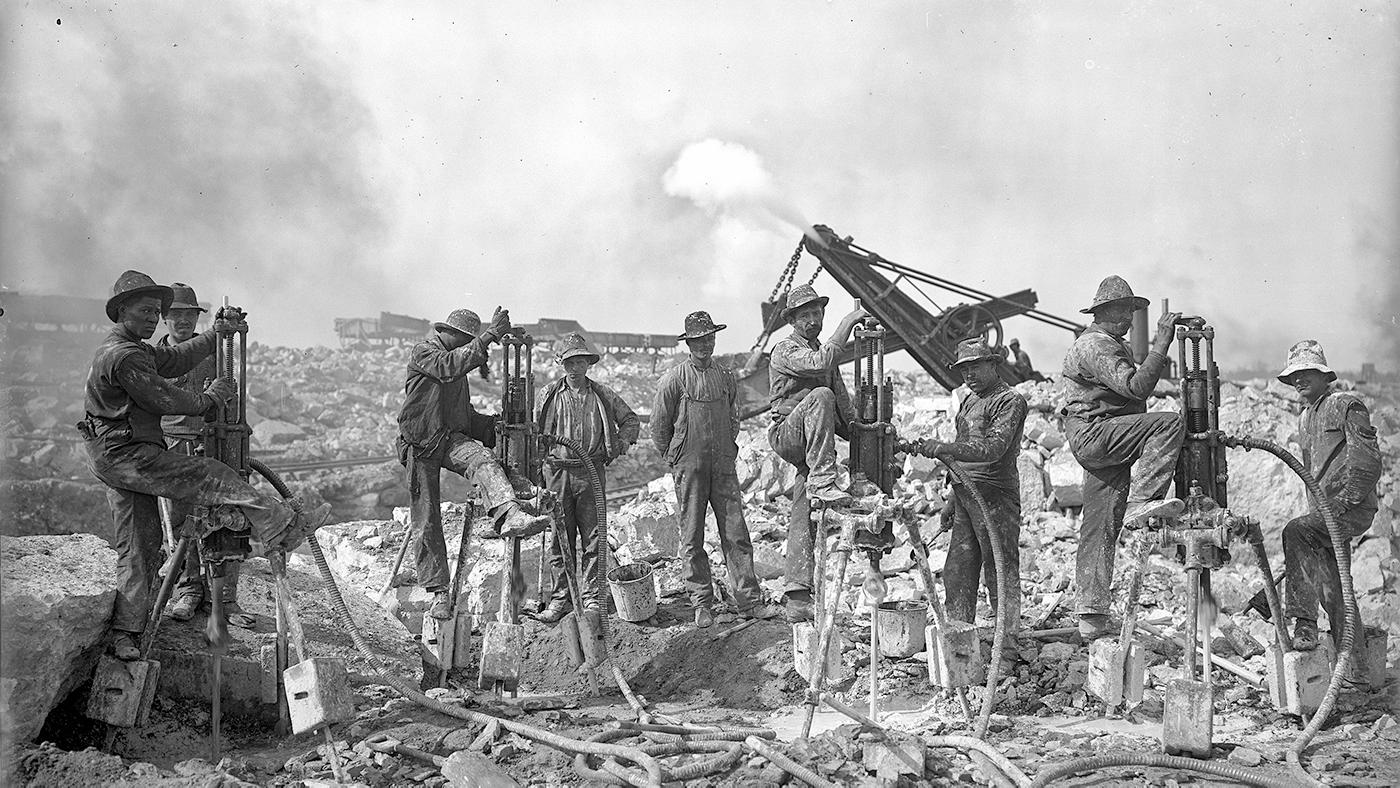

A Chicago-style bungalow in Skokie, Illinois. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A Chicago-style bungalow in Skokie, Illinois. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

However much the bungalow was a symbol of middle-class success, it was a dream reserved primarily for white families. Through most of the halcyon days of the growth of the Bungalow Belt, African Americans were legally prohibited from buying bungalows or living in many of the neighborhoods where the homes could be found. Racially restrictive covenants included in housing contracts prevented people from selling homes to African Americans, while discriminatory lending practices made mortgages impossible to obtain for many families of color. All of this was federally sanctioned and even encouraged by the Federal Housing Administration, until the Supreme Court ruled in the 1948 case Shelley v. Kraemer that racially restrictive covenants were unconstitutional. (An important precedent for Shelley was a case brought by the father of the playwright Lorraine Hansberry after he bought a home in the then-white Chicago neighborhood of Washington Park.)

In the 1950s and ‘60s, African Americans were finally able to move into the homes and neighborhoods of the Bungalow Belt – but as they did so, white families, spurred by a variety of economic and social reasons, began leaving for the suburbs and that mythical white-picket-fence American Dream. (A dream that typically did not include black people – there’s a reason suburbanization was known as “white flight.”) As the decades progressed, many of the neighborhoods of the Bungalow Belt shifted from white ethnic enclaves to African American or Hispanic areas.

In the past couple of decades, bungalows have begun to be recognized for their architectural significance and have again become a coveted form of housing as families move back into the city and search for the kinds of historic details that bungalows offer in abundance. In 2001, the city announced the Chicago Bungalow Initiative, which provides tax incentives to homeowners to restore and preserve the homes, and to recognize their historical importance. There are Bungalow Historic Districts, annual awards for restored and rehabilitated bungalows, and tips for adapting and retrofitting the homes to make them more efficient and eco-friendly. A classic twentieth-century home is being re-imagined and reclaimed for the twenty-first century.